Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

Outwith his native Denmark, the country home to the most architectural works by Arne Jacobsen is Germany.

Yet the vast majority of them remain popularly unknown.

As does Arne Jacobsen’s partner on his German projects: Otto Weitling

With the showcase Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany, the Felleshus Berlin not only set the record straight but allow for some fresh reflections on both Arne Jacobsen and our relationships to and with architecture and our built environments……

Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

Born in Copenhagen on February 11th 1902 Arne Emile Jacobsen is a regular guest in these dispatches, and so, with your permission, we’ll skip over the wider Jacobsen biography, and proceed directly to that part concerning his relationship with Germany, a country whose cultural (hi)story was an early interest of the young Arne, and a relationship that goes back to the earliest days of his career; as we noted from the exhibition Arne Jacobsen – Designing Denmark at Trapholt Kolding, among the varied influences on the young Arne one of the more important was the developing architectural understandings and positions of 1920s Germany, including moments such as the Neues Frankfurt urban planning project, the 1927 Weissenhofsiedlung building exhibition in Stuttgart, and Bauhaus, for all in its Dessau incarnation. And one (future) Bauhäusler in particular: “as a newly qualified architect I went, at the end of the 20’s to Berlin, which was then very active on the cultural field. It was there that I attended an exhibition of works by Mies van der Rohe: I was both surprised and convinced by what I saw …. Since this experience at Berlin Mies van der Rohe has, for me, become the most important architect of our time.”1

And much as many of Mies’s early works are to be found in Berlin, so Arne Jacobsen’s first German project, the so-called Atrium Houses: a group of bungalows constructed from prefabricated concrete elements, each with a prominent garden so designed as to merge with the interior; bungalows realised in context of the 1957 Interbau building exhibition, an exhibition of contemporary architecture and construction that was also, primarily?, about rebuilding West Berlin’s War damaged Hansaviertel; an exhibition which although it didn’t feature Mies van der Rohe did feature “Bauhaus” in the persons of Walter Gropius, Eduard Ludwig and Gustav Hassenpflug, alongside a further, impressive, roster of International Modernists of various ilks and ages including Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, Egon Eiermann and the Dane Kay Fisker, one of Jacobsen’s former tutors at the Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi, and who as an influence on the young Arne was every bit as important as a Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. And quite aside from tending to confirming Arne Jacobsen’s position in late 1950s architecture, Interbau Berlin also represented Jacobsen’s first, major, opportunity to present his understandings of architecture to an international public outwith Denmark.

And similarly also offered Jacobsen a major, international, platform to present his understandings of design, and that not just as expressed by his own designs; at Jacobsen’s insistence, the Atrium Houses were furnished and fitted exclusively with Danish products. If with a very heavy Jacobsen focus, including the first public appearances of what would become known as the Grand Prix side chair and 3300 sofa for Fritz Hansen and the AJ Lamps for Louis Poulsen, and thus stood, if so one will, as a miniature exhibition of Danish craft and design in the heart of West Berlin. And as such can be considered as being very much part of the swathe of officially sponsored “Scandinavian” craft and design exhibitions of the 1950s and 60s that were to be so central to establishing the ongoing fascination, obsession, with anything and everything considered to have a perceived “Scandinavian” trait.

And then shortly after Interbau Berlin Otto Weitling entered Arne Jacobsen’s employ.

Mainz Rathaus, as seen at Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

Born on January 12th 1930, and thus a good generation younger than Jacobsen, Otto Claudius Weitling, in many regards, personifies the German-Danish (hi)story of his birthplace: when Weitling’s parents moved from Wiesbaden to Hadersleben it was Prussian, and one of the most northerly towns in the German Reich; by the time of Otto Weitling’s birth Haderslev, as with the rest of the northern part of the Duchy of Schleswig, was Danish. And remains a region, on both sides of the contemporary border, that is very much defined by its shared Danish-German, German-Danish histories and its contemporary German-Danish and Danish-German communities. Similarly, Otto Weitling, who with a German-Danish biography behind him, was, in many regards, excellently placed to develop a Danish-German legacy.

But first Otto Weitling had to study architecture.

Or rather first, and as Jacobsen himself once had, Otto Weitling had to undertake a formal training in masonry and construction, before he could enrol to study architecture at Copenhagen’s Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi, and which he recalls “was a good training; I had very good teachers. For one, Professor Kay Fisker.”2 Thus tending to underscore not only Kay Fisker’s importance to the development of 20th century architecture, but allowing for reflection on the role of continuity in any architecture and design school’s teaching staff in the development, establishment, and maintenance of understandings of architecture and design.

Graduating from the Kunstakademi in 1956 Otto Weitling joined Arne Jacobsen’s office in 1958, and where amongst his first responsibilities he was involved in the development of the Toms Chocolate Factory in Ballerup and the SAS Royal in Copenhagen, that grand d’hotel moderne that stands so in the focus of Jacobsen’s oeuvre. And which, as noted from Designing Denmark, was not only an international orientated project but, in many regards marks the start of Arne Jacobsen’s international architectural career: before the SAS Royal Jacobsen was, +/-, only active in Denmark, Interbau Berlin being one of the very few exceptions, post-SAS Royal Jacobsen was increasingly active internationally.

And nowhere more so than, the then, West Germany.

And that, not solely, on account of Jacobsen’s long standing interest in and relationship to Germany.

Rather can be understood in context of the strong development of the West German economy in the 1950s and 1960s, a development which, and coupled with the ever increasing distance from the 1930s and 1940s, expressed itself in innumerable ways in German society and culture, including in an increase in construction, and that across the private, commercial, industrial and civic sectors. And for all an increase in buildings contemporary in terms of their materials, construction principles, structural elements, spatial relationships, functional understandings, formal expressions, et al; of works which confirmed that West Germany was forward looking, dynamic, open, transparent, part of the international community, and wasn’t that which it had been a few years previous. And thus a moment apparently made for an architect such as Arne Jacobsen. And so it came to pass; and from the mid-1960s onwards Arne Jacobsen realised seven projects in Hannover, Hamburg, Fehmarn, Mainz and Castrop-Rauxel.

Or more accurately, the in 1964 established company Arne Jacobsen + Otto Weitling Associates, realised seven projects in Hannover, Hamburg, Fehmarn, Mainz and Castrop-Rauxel; the formal co-responsibility of Otto Weitling for the design and development of the projects being as popularly unknown as the projects themselves.

And that despite them all standing in full public view.

The Hamburgische Electricitäts-Werke, HEW, administrative building Hamburg, as seen at Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

If geographically dispersed.

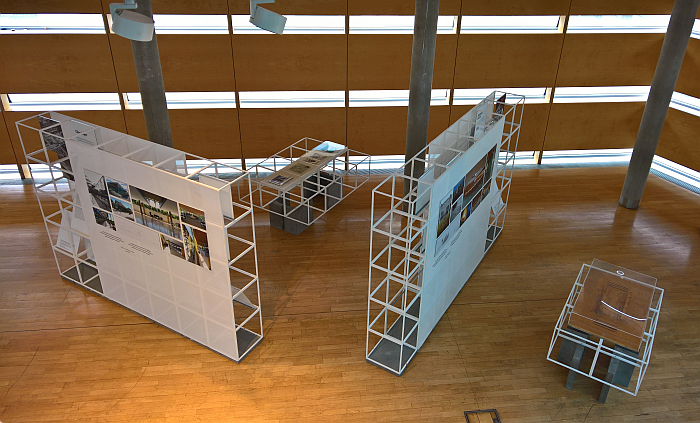

Gesamtkunstwerke allows for a condensed tour to and through Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen’s German works.

A tour which begins with a brief introduction to its central protagonists, and also a brief introduction to Kaare Klint, that Grand Doyen of Danish furniture design, a further important tutor of Jacobsen’s at the Kunstakademi, a designer whose functionalist understandings were discussed in context of the exhibition Nordic Design The Response to the Bauhaus at The Bröhan Museum Berlin as serving as a bridge between pre-War German Functionalists and post-War Danish Functionalists. And a designer who is presented in Gesamtkunstwerke by his 1933 Safari Chair, a work of which Jacobsen was an early adopter and which stands at the start of Gesamtkunstwerke as the curator’s metaphor for Jacobsen and Weitling’s approach to architecture: modular, systematic, use of pre-fabricated components, visually light and with a very clear commitment to handwork.

A metaphor that can be explored and considered on the subsequent (near) chronological tour through Jacobsen and Weitling’s German canon; a tour on which we’ll resist the very real temptation, and very strong desire, to take prolonged, lingering, stops at each location, and abbreviate down to a whistle-stop tour. Starting at Jacobsen’s (solo) Berlin Atrium Houses, before moving on to the 1966 Glass Pavilion in the Herrenhäuser Gardens in Hannover, the only component of a much larger, and much more free-flowing, expressive, project to be completed, and thus one of numerous “what if” moments encountered along the way; and from Hannover moving on, northwards, to Hamburg and the former Hamburgische Electricitäts-Werke, HEW, administrative building, a 13 storey, reinforced concrete skeleton construction composed of four offset, glass-fronted, blocks, a work that represents Jacobsen and Weitling’s first large scale, high-rise project in Germany….. and the last of the projects Arne Jacobsen saw completed.

On March 24th 1971 Arne Jacobsen died unexpectedly in Copenhagen, aged just 69, and, as Gesamtkunstwerke helps underscore, with both an awful lot of interesting and relevant ideas still to develop, and positions and understandings to contribute to the global architectural discourse.

Jacobsen’s sudden death leaving numerous international projects in varying states of incompletion; a completion that was taken on by the newly formed company of Dissing+Weitling: the former, Hans Dissing, having served for many years as Arne Jacobsen’s office manager, and thus with responsibility for the management and direction of projects, and accordingly well aware of what was planned and why; the latter, as we all now know, co-author of all the German projects. Projects which at the time of Jacobsen’s untimely death were all either under construction, or good to go.

Artworks by Arne Jacobsen, as seen at Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

The first Weitling + Jacobsen project Dissing+Weitling completed was the Christianeum school in Hamburg, a work that in its internal organisation and theoretical basis can be considered very much in context of Jacobsen’s 1957 Munkegård school in Gentofte, albeit, or as far as we can ascertain, without the joyously impudent folded plywood desks. From Hamburg the tour moves on to Mainz and Jacobsen and Weitling’s Rathaus, a work conceived as much as a cultural event space as a civic political space, a work whose marble facade echoes the, more or less in parallel developed, Danish National Bank in Copenhagen, albeit with a much more expressive, animated, countenance than the more reserved, restrained, banker’s, facade in Copenhagen, and a work which following years of (charged) public debate isn’t in the process of being demolished, but of being renovated.

A renovation also being undertaken, albeit when only v–e–r–y slowly, of the so-called Forum in Castrop-Rauxel, an ensemble completed in 1978 and which encompass a Rathaus and a multifunction event hall; a project originating from a 1965 closed competition whose participants included, amongst others, Alvar Aalto, Egon Eiermann and Paul Schneider-Esleben, a list which tends to indicate what the local authorities were seeking. That which the authorities sought proved however more ambitious than their budget and consequently was never completed as planned/envisaged. And in many regards is defined today by the fact it was never completed as planned/envisaged.

Gesamtkunstwerke ends its tour through the German works of Jacobsen and Weitling on the Baltic Sea island of Fehmarn, and thus, if one so will, symbolically, between (mainland) Germany and Denmark, and where with the Seebad Burgtiefe Weitling and Jacobsen developed a hotel complex that in addition to accommodation features a spa/pool facility and an event space; a project realised against the background of the 1960s tourist boom on West Germany’s North and Baltic Sea coasts; and a project whose so visually dominating triumvirate of 17 storey hotel blocks weren’t designed by Jacobsen and Weitling as 17 storey hotel blocks. Or to be so visually dominating. But were, independently of the architects, built as such. And a project which is not only, by all accounts, and as with so many of Weitling and Jacobsen’s projects, in general need of renovation, but which has already lost one unrenovated building to the bulldozers.

And thus a project which not only ends the tour through the German works of Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling, but leads, along with the varied thoughts and impressions collected elsewhere on the tour, very neatly on into one of Gesamtkunstwerke‘s sub-themes, our relationships to and dealings with architecture.

Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

Here is, regrettably, not the time nor place for that discussion, we wish it were, and we did start going down that path; however, limits of time and space forced us to beat our retreat and restrict ourselves here to noting the very pleasing manner in which Gesamtkunstwerke not only provides for an introduction to Jacobsen and Weitling’s German works but uses them as conduit for further, wider, considerations.

And which we’d argue is important; architecture, the built environment, is as much a question of democracy as one of art or statics; our relationships to and dealings with architecture and urban spaces, both as individuals and as communities, is/are essentially of an environmental, economic, behavioural, cultural, social, et al nature and thus affects us all both directly and indirectly. And in real terms rather than the semiotics that underscore much architecture, certainly public/civic architecture.

Yet, and as with most all subjects which impact on our democracies, all too often popular discourses on architecture are undertaken on subjective, at times emotive, levels; and that not just involving subjects such as the individual appreciation of a formal expression or the choice of material, but involving, and amongst other subjects, questions of a (perceived) typicality, of the character of a particular town or space, or on the (perceived) relevance of the name of the architect responsible, and is a discourse that invariably involves reference to the “historic”, a phrase that could hardly be more malleable nor freely definable. And clearly can’t be the basis for decisions of any sort.

And a state of affairs that can be understood and followed in the various discourses concerning not just the fate of Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen’s German projects, but their genesis and development. Or occasional non-development.

Gesamtkunstwerke is an invitation, an imploration, to consider Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen’s German projects from more objective positions; to consider not just what they are, but to consider why they are what they are, to consider how they became what they are, to consider what differentiates what they are from what they are not, to consider them as works from their time, as works in our time, and what that means, to consider, as Jacobsen once did of Mies van der Rohe, the “ideas expressed”3 in and by the works. Or put another way, to consider them as the complex entities they are.

And if you do that it, and you will, it’s all but automatic, it is only a very short step to moving on to considering other buildings, other spaces, in a similar manner, and thus of using the German works of Jacobsen and Weitling, the positions and understandings Jacobsen and Weitling incorporated into and embodied in their works, as tools to fine tune your own understandings and positions.

Which, again, we’d argue is important. As we’ve oft opined, decisions on architecture are way too important to be left to architects, they need to bubble up from a community. Which doesn’t (necessarily) mean collective decision making processes per se; does however require the development of more objective understandings of architecture and our complex relationships with the built environment within the wider community. In its condensed focus and the myriad considerations and questions contained in and across the presented projects, Gesamtkunstwerke is a very relevant and stimulating contribution to that process.

Chair designs by Arne Jacobsen, as seen at Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

Beyond the architecture Gesamtkunstwerke also briefly considers Arne Jacobsen’s furniture and object design, something that is and was Arne Jacobsen without Otto Weitling, including, and amongst other objects Jacobsen’s taps for the Danish National Bank and produced by Vola, his clock design for HEW, clocks being, as previously noted, very important for Arne Jacobsen, and also examples of his furniture design, including a Series 7 side chair from Seebad Burgtiefe Fehmarn, and an upholstered Series 7 armchair from HEW Hamburg.

And which brings one to reflections on the Gesamtkunstwerk that underscored so much of Jacobsen’s approach to and understanding of his work; and reflections Gesamtkunstwerke pleasingly allows both in terms of the interior and the exterior.

The former not just in context of the fixtures and fittings, but also in context of colour. With all the popular focus on Jacobsen’s furniture the colour schemes he employed in his interiors, his understanding and use of colour as a functional component of a space, his understanding of human relationships to colour, can become an all to easily overlooked aspect of his work. Yet was central to his interiors; and lest we forget one of Arne Jacobsen’s earliest passions was art, a passion that not only never left him but informed his understandings of his work. The German works offering a very nice, succinct but thus all the more intense, opportunity to reflect in more detail on Jacobsen and colour. And also on Verner Panton; for lest we also forget, a young Verner Panton spent a couple of years in Jacobsen’s employ, and what is a, the, defining feature of Panton’s interiors……

Arne Jacobsen’s other life-long passion was botany and horticulture, and as previously noted, wherever he got the chance Jacobsen developed the gardens and green spaces associated with his buildings; and in Germany he got the opportunity not just in context of the Atrium Houses in Berlin, but also, for example, in context of the two Hamburg projects. And there is obviously a delicious “what if” in context of Castrop-Rauxel and Fehmarn which he never saw completed, and thus never got the opportunity to fully develop the exterior, to influence the final composition. And garden design work that is not only all too often forgotten in the Jacobsen Gesamtkunstwerk, but also provides a further, equally all too often overlooked link to Mies van der Rohe, or at least early Mies who designed the gardens for many of his Neoclassic, Landhaus, era projects in Berlin and Neubabelsberg. Early projects for which he possibly also designed the furniture. Although we have no more than insubstantial scraps to cling to as evidence.

With Jacobsen the situation is much clearer, and whereas for his German projects he may not have designed furniture on the scale he did for his pre-War Danish projects, nor employed new designs on the scale he did post-War in projects such as the SAS Royal Copenhagen, Munkegård school Gentofte or St Catherine’s College Oxford, the German works of Jacobsen and Weitling were furnished solely with Jacobsen’s designs. And occasionally works that arose parallel to the projects, and thus, effectively, in unison with them; something most joyously represented by the 3400 steel tube and leather upholstery chair and accompanying table from 1971 for Fritz Hansen, works which represent Jacobsen’s last furniture designs and which found a very natural home in the Mainz Rathaus. And where post-renovation they will, if we’ve understood the plan correctly, continue to find a home.

And indeed most all Weitling and Jacobsen’s German projects are still home to original Jacobsen furniture from the 1960s and 70s, albeit by all accounts, and as with the works themselves, in varying degrees of distress. A state of affairs which reminds us all of the renovation of the SAS Royal in the 1990s, in the course of which the interior was gutted and Jacobsen’s fixtures, fittings and furniture unceremoniously dumped in skips. Unimaginable today, but in the 1990s Arne Jacobsen was so out in Denmark. Why is he back in today? And what does that teach us? And what do the (hi)stories of his architectural projects in Germany tell us about Germany’s relationship(s) with Arne Jacobsen?

Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Berlin

Presenting itself primarily in photos and short bilingual German English texts Gesamtkunstwerke allows for a brief, if informative, entertaining and clearly comprehensible, introduction to the German works of Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling. Or at least the built works. Or at least the vast majority of the built works. The former Novo Pharmaceuticals office building in Mainz is not included, a, for us, regrettable exclusion, not least because the changes that have been made to the interior are, as with the gutting of the SAS Royal, a not unimportant component of considerations and reflections on not only our understandings of Arne Jacobsen and our relationships to and dealings with the works of Arne Jacobsen, but also our understandings of, relationships to and dealings with architecture in general. Of considering architecture (primarily) objectively not subjectively. And for all the very important question of adapting existing buildings to new purposes, new realities, new functionalities, something we’ve mused upon previously in context of Egon Eiermann and feel certain we’ll return before all too long in context of Jacobsen and Weitling. Novo Pharmaceuticals’ exclusion does however allow impetus, a gateway, for a little more research on your own. One of several paths that Gesamtkunstwerke opens, and which we’d very much encourage you all to follow.

One of the more important being the one that leads to Otto Weitling, an architect who through the development of the Gesamtkunstwerke project Hendrik Bohle and Jan Dimog have brought firmly back into the (hi)story of not just 20th century German architecture, but back into Arne Jacobsen’s oeuvre. No architect is themselves alone, all projects are a team effort, the important on Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling’s German projects is that they are joint projects.

An understanding which not only necessitates becoming better acquainted with Otto Weitling and his contribution to the development of architecture, but of understanding the German works in context of Arne Jacobsen’s wider oeuvre.

A process aided and abetted by the fatefully unintentional but joyous mix of works the pair realised in Germany: civic buildings, cultural buildings, a school, an office block, a hotel complex. And thus allowing not only for free and ready comparisons between the projects in their similarities and differences, in how Jacobsen and Weitling varyingly and consistently approached the differences and similarities of the briefs, situations and demands, but also of a comparison with works of the same genres developed by Jacobsen in Denmark pre Otto Weitling, and the therewith associated differentiated considerations on Arne Jacobsen’s architecture, on Arne Jacobsen’s Gesamtkunstwerk, that arise.

And a process supported not only by the important insights Gesamtkunstwerke offers on the components of the projects that weren’t realised, for all in Hannover and Castrop-Rauxel, and those components realised outwith the initial plans, for all on Fehmarn, but also through the pair’s unsuccessful competition entries for new Rathauses in Cologne, Essen and Marl, works which aren’t in the exhibition, but are in the accompanying book, and works which not only allow for an extended understanding of Weitling and Jacobsen’s oeuvre, but also allow for another very nice “what if?” moment. For all in context of Cologne.

And last, but by no means least, Gesamtkunstwerke opens a path to approaching a better understanding of Arne Jacobsen’s relationship with Germany, not just in terms of the contribution of Germany’s cultural (hi)story to the development of Arne Jacobsen, a contribution that even his experiences with the Nazis couldn’t cloud; but, also the contribution of Arne Jacobsen to the development of Germany’s cultural (hi)story, how Arne Jacobsen took the understandings Germany enabled him, developed them in context of other impulses, and reintroduced them to (West) Germany’s ongoing cultural, social and architectural development, and how that contribution feeds into contemporary considerations, positions and understandings.

And how much more nourishment that contribution could, can, provide once the German projects are popularly better known……..

At this point we would normally note that Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany runs at Felleshus, The Nordic Embassies, Rauchstraße 1, 10787 Berlin until….. However on account of local Corona regulations, while it did open on October 30th, it closed on November 1st. All going to plan will however re-open in December and will be on show until Sunday January 10th.

When it will set off on a 15 month tour over Fehmarn, Mainz, Hannover, Castrop-Rauxel and ending in Hamburg; and, importantly, a tour on which, in most all cases, it will be presented in the actual works themselves. Before in the course of 2022, all going to plan, it will be shown in Denmark.

Which is largely why we decided to post this now even though the Berlin presentation is currently closed; for important and worthwhile as the Berlin presentation is, it is also the opening act, an unveiling if one will, of a much larger, ongoing, project. A project that goes beyond the exhibition, a project that is also the accompanying bilingual German/English book, a work that goes into much more detail than the showcase can or could. And a project which, we’ll argue, will grow as it undertakes its tour, and as it, hopefully, stimulates not only interest in Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling’s works but debate, preferably objective, critical, debate, on those works. Or as Otto Weitling opined in 1974 of the Mainz Rathaus, “ein Haus, über das man nicht redet, ist meist nicht der Rede wert”, “a building that isn’t talked about is usually unworthy of discussion”4 All of Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling’s German projects are not only worthy of discussion, but need to be discussed.

And we also decided to post now as (hopefully) a stimulation for all in Hannover, Hamburg, Mainz, Castrop-Rauxel and/or on Fehmarn who are looking for meaningful, outdoor, responsibly socially distanced, activity this locked-down November to get out and discover your local Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen work. And thereby not only become better acquainted with that work but (hopefully) setting you off on an interesting, invigorating and important journey of your own.

Full details, including dates and information on the coming tour through Germany, and thus very much the space to watch for updates, can be found at http://gesamtkunstwerke.eu/

And as ever in these times, if you do feel comfortable visiting any exhibition, please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious….

- Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling, in the foreground, visiting the consruction of Mainz Rathaus, undated (Photo Klaus Benz, © and courtesy Stadtarchiv Mainz)

- Atrium Houses, Berlin by Arne Jacobsen, 1957 (Photo Hendrik Bohle © and courtesy Jan Dimog and Hendrik Bohle)

- Glasfoyer Herrenhäuser Gardens, Hannover by Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen, 1966 (Photo Hendrik Bohle © and courtesy Jan Dimog and Hendrik Bohle)

- HEW-Zentrale, Hamburg by Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen, 1969 (Photo Hendrik Bohle © and courtesy Jan Dimog and Hendrik Bohle)

- Christianeum Hamburg by Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen, 1971 (Photo Jan Dimog © and courtesy Jan Dimog and Hendrik Bohle)

- Seebad Burgtiefe, Fehmarn by Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen, 1973 (Photo Jan Dimog © and courtesy Jan Dimog and Hendrik Bohle)

- Mainz Rathaus by Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen, 1973 (Photo Hendrik Bohle © and courtesy Jan Dimog and Hendrik Bohle)

- Forum Castrop-Rauxel by Otto Weitling and Arne Jacobsen, 1976 (Photo Jan Dimog © and courtesy Jan Dimog and Hendrik Bohle)

1. Arne Jacobsen, Bauen + Wohnen, Nr. 5, May 1966 page 190, and quoted in the exhibition.

2. Hendrik Bohle and Jan Dimog [eds.], Gesamtkunstwerke – Architecture by Arne Jacobsen and Otto Weitling in Germany, Arnoldsche Verlag, Stuttgart, 2020 page 32/33

3. Arne Jacobsen, Bauen + Wohnen, Nr. 5, May 1966 page 190, and quoted in the exhibition.

4. Bruno Funk and Wilhelm Jung [eds.], Das Mainzer Rathaus, Stadtverwaltung Mainz 1974, qouted in ibid page 26/27

Tagged with: Arne Jacobsen, Berlin, Castrop-Rauxel, Fehmarn, Felleshus, Gesamtkunstwerke, Hamburg, Hannover, Mainz, Otto Weitling