#officetour Milestones – The Mannesmann-Haus by Peter Behrens

“With every new building the first task is to clarify the needs that will arise in context of its use”,1 opined Peter Behrens on December 10th 1912 at the official inauguration of the new administrative HQ for the Prussian industrial concern Mannesmannröhren-Werke AG.

And while Peter Behrens was certainly not the first to opine such, with the so-called Mannesmann-Haus in Düsseldorf he realised one of the earliest large office buildings designed to evolve and develop as those needs evolved and developed.

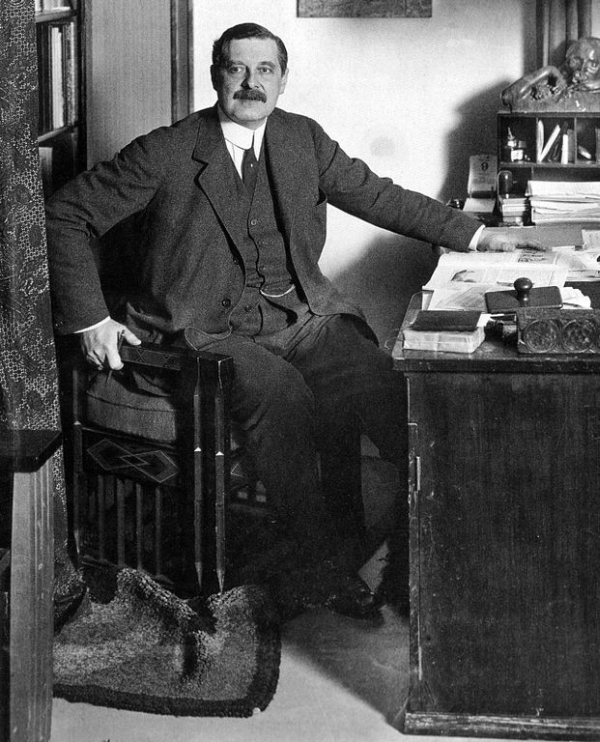

Born in Hamburg on April 14th 1868 Peter Behrens originally trained and practised as an artist, before art became applied art and architecture, and Behrens developed into one of the leading protagonists of German Jugendstil, and also an important practical and theoretical intermediary in the development of what is popularly known today as International Modernism. That we’ve discussed Peter Behrens’ life and work on numerous occasions in these dispatches, for all in context of the triumvirate of exhibitions to mark his 150th birthday, we refer you there dear reader for the fuller background and biography.

And concentrate here on the Mannesmann-Haus.

Established in 1890 Mannesmann initially focussed on the production of seamless steel tubes via a novel process developed and patented by the brothers Reinhard and Max Mannesmann; seamless steel tubes which offered a myriad advantages over their competitors’ seamed tubes, and thus as demand for steel tubing grew in context of the increasing global industrialisation of the early 20th century, so grew Mannesmann, thereby establishing themselves as one of the leading industrial concerns of the period.

A rate of growth and a prominence that can understood by the fact that in 1910, after just 20 years in business, Mannesmann required/desired a representative HQ building in a prominent location; and found that location on the banks of the Rhein in the heart of Düsseldorf, at that time not only one of Europe’s principle centres for steel and heavy industry, but as Horst A. Wessel notes, “in the metropolitan area and its immediate vicinity there were more tube works than anywhere else in the world”.2

In order to suitably adorn their prominent site, to suitably stake their claim to their position in Prussia’s steel tube capital and the global steel industry, Mannesmann initiated an architectural competition in January? February? 1910,3 soliciting entries from five Düsseldorf based architects, including Alfred Fischer, Richard Hultsch and Wilhelm Kreis.4 And a competition for which Peter Behrens, who had served as Director of the Kunstgewerbeschule Düsseldorf between 1903 and 1907 and who thus had a Düsseldorf link, was engaged as a consultant “to assess the proposals and to comment on them objectively”.5 How it came that Behrens switched from being an objective consultant to a subjective commissioned architect is sadly lost in the mists of time, or perhaps simply obscured in the depths of the Mannesmann archive, but one can’t help feeling that something a little improper must have happened along the way. Certainly that the other five must have been more than a mite miffed at the turn of events. For it was a very notable commission.

What (hi)story has recorded is that in November 1910 the authorities in Düsseldorf approved Behrens’ proposal, in April 1911 construction began, was completed just 19 months later in November 1912 and in December 1912 Behrens’ Mannesmann-Haus was formally inaugurated. And would remain, with a small Second World War enforced interruption, Mannesmann’s HQ until December 2012 when Vodafone, who had taken over Mannesmann in 2001, relocated to a new complex across the Rhein in Düsseldorf-Oberkassel.

At the time of the Mannesmann commission Peter Behrens had been a practising architect for less than a decade, and although an architect whose star was very much ascending, for all through his industrial buildings for AEG Berlin, he had never realised either a representative commercial office building or a work of such scale and complexity.6

Yet despite his lack of actual practical experience, Peter Behrens wasn’t short of theoretical positions in context of the representative commercial office building.

“It seems as if the logical steadfastness, the energy and the dependable efficiency of the industrial and wholesale merchant class, to which we thank the rapid economic development of our Empire, has not always been recognised in clearly and logically developed ideas of form”, opined Peter Behrens in his 1912 address, presumably to an audience featuring many an energetic, dependent, steadfast, industrialist and wholesale merchant, “rather, such all too easily falls victim to a dilettantish tendency towards the romantic and opulence”, and that, “it is incomprehensible why a building that serves serious and purposeful work does not always have a bearing that reflects this seriousness, why such buildings are still so often fraught with bay windows, quaint gables and the familiar overabundance of gaudy architectural ornamentation”.7

And that being by no means just Behrens position, but rather representing a very succinct articulation of much of the criticism of the Art Nouveauists of the heavily ornate historicism of the 19th century, that crime that an Adolf Loos had decried a couple of years prior to Behrens’ Düsseldorf commission, and whose elimination, in many regards, and simplifying dangerously, was the path that led to (dogmatic?) Functional Modernism.

For his Mannesmann-Haus Behrens’ sought to reflect this seriousness through “the principle of simplicity”, through a work whose external articulation was not only suitably representative, but also clear and logical. And found his answer, as Behrens so oft did, in classical architecture, if less in the Karl Friedrich Schinkel who so regularly served as an informant for Behrens and more in the Italian Renaissance: Behrens quoting in his 1912 address the 15th century Palazzo Strozzi and Palazzo Riccardi in Florence as inspirations, as prime examples of an “unbroken simplicity” of facade and of a “cubic monumentality” of presence, and quoting in his Mannesmann-Haus the Florentine Palazzi in the vertical arrangement, the contrast between the rusticated pedestal and the sleeker upper floors and the roof with its short but defiant cornice. And thereby achieving a monumental simplicity that both reflects the serious and purposeful of the work within and also deliciously juxtaposes with the romantic, the opulence, the bay windows, the quaint gables and the familiar overabundance of gaudy architectural ornamentation, of the houses in Oberkassel on the other side of the Rhein, and which, more or less directly, face the monumentally simple Mannesmann-Haus.

And as with the exterior so the interior, where Peter Behrens equally sought to express the serious and purposeful work undertaken via the principle of simplicity.

Which poses the question, what is simplicity in context of an office building?

As noted above, the Mannesmann-Haus was Behrens first large scale commercial office project, and reading his description of its genesis and development one gets the impression that while he was very clear on questions of the exterior, on questions of the interior it was (largely) a case of learning by doing.

Or put another way, having discussed the requirements with the Mannesmann management Behrens opines that developing such an office building isn’t about defining the required floor space alone, rather “it depends on even more important things: namely, the organic structure of such a large administrative body, the functional relevance of its individual components to one another, to know and understand the nervous system, and to create the life-supporting body for this complicated being.”8 A comparison of the office as a living organism which reminds of, and amongst numerous other possible examples, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1902-06 Larkin Administration Building in Buffalo with its internal organisation defined by the flow of work through the space, or Le Corbusier and his Organisation rationelle, which as depicted, for example, in context of his 1933 competition entry for the new Rentenanstalt in Zürich is very much an office building as a organic entity.9 And not uninterestingly from autumn 1910 until spring 1911, and thus in the final stages of the planning of the Mannesmann-Haus, the then, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret was in Peter Behrens employ. And a Charles-Édouard Jeanneret we’ll return to real soon.

But for all Behrens came to understand that as an organism an office building is anything but static, rather, “whenever I tried, in cooperation with the management, to distribute the individual departments in the building, to determine the most suitable place for the individual offices, it always transpired that depending on whether the current business situation or a future development was taken into account, that an alternative distribution offered even greater advantages”, with the consequence that “it seemed to me that a single, ideal arrangement could never be determined”10

Spring forward 100+ years and has so very much changed in commercial office planning?

The main entrance of the Mannesmann-Haus, Düsseldorf by Peter Behrens, the only ornamentation on the facade….

Behrens’ solution was as elegant as it was, for its day, (near) revolutionary: through the use of an iron skeleton construction – the exterior stone that is so dominant is but cladding – Behrens was able to do away with fixed, load bearing, internal walls and instead separated the individual offices on the second and third floors, those floors where employees laboured, with “hanging, soundproof shear walls that can be easily removed or set up elsewhere”.11

And thus allowed “the ability to continuously change the size of individual rooms” and thereby, allow “the greatest possible utilisation of the space for workplaces”; a flexible and variable floor plan system that allowed management to respond to the current business situation and/or future developments in that they could freely decide whether to divide the space into “many small offices or several large, overseeable, open office spaces.” Or any required combination of such. And reconfigure the space as the situation evolved and developed.

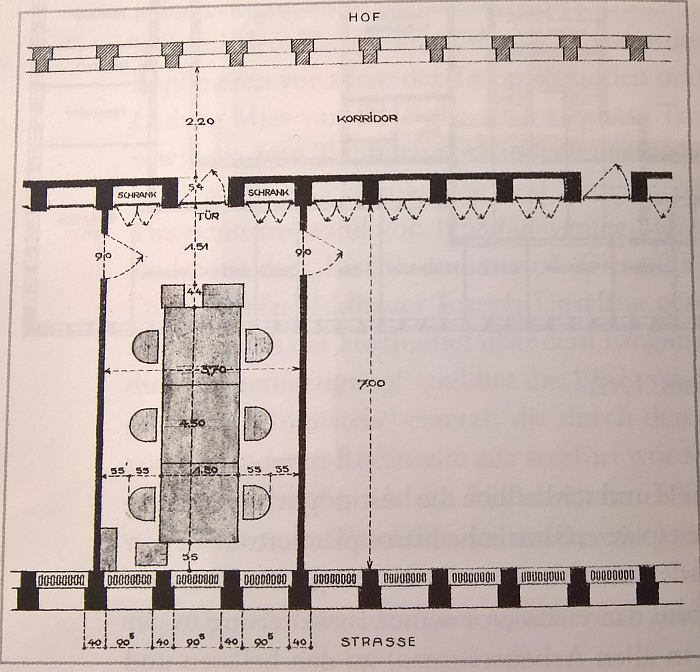

The basis of Behrens’ plan was a standardised office unit measuring 7m by 3.7m, the dimensions being selected so as to allow for the comfortable placing of a desk with six chairs around it plus space for filing cabinets and typewriters, and a standardised office unit which in the floor plan served as the repeating “cell of the body” to remain in Behrens’ organic vocabulary. Or the repeating “cell in a honey-comb” to quote Louis H. Sullivan, one of the first architects to reflect critically on office buildings, and who in 1896 proposed that large office buildings should be composed of “an indefinite number of stories of offices piled tier upon tier, one tier just like another tier, one office just like all the other offices”12; Behrens maintaining the standardisation of Sullivan’s vision but refining it through not demanding similarity but enabling variety, not demanding “one tier just like another tier” nor that one office be “like all the other offices”, but allowing each tier and each office the freedom to be that which it needs to be, whenever it needs to be.

In addition to allowing for internal flexibility the iron skeleton also allowed for the use of near room height, 90.5 cm wide, windows, each office cell having three such windows, separated by the 40 cms of the skeleton, and thus a “light area of around 8 square meters” per standard office unit, and thereby an illumination which, according to Behrens, “on account of the reflection from the walls and the ceiling appears diffuse, without significant shadow formation. As a result the room, with its relatively great depth of 7m, is evenly lit all the way up to the wall unit opposite the window”. A quality of illumination that allowed Behrens to claim that in 1912 the Mannesmann-Haus, was “the brightest and best lit office building currently in use”.13

Much as we’d like to claim Peter Behrens was the very first to use the inherent properties of metal skeleton construction to enable a variable floor plan design, he wasn’t. But was arguably the first to employ the properties to such an extreme degree and in such a large, complex, commercial office building. While the current realities have hindered a full global search of and for forebearer works14; staying in a more accessible, and in context of Behrens relative and appropriate, Germanic context, not only was the variable floor plan a recurring feature of numerous late-19th century Hamburg Kontorhäuser15, but as Brigitte Schlüter notes, in his 1908-1911 Turmhaus for Krupp in Essen, and thus an office building for another Rheinland steel mammoth, Robert Schmohl developed a variable floor plan similarly based around a standardised office unit with three windows. However, whereas Schmohl’s plan foresaw moving the internal walls in steps of three windows, within the confines of the basic office unit, Behrens plan allowed for the walls to be moved one window at a time, thus allowing near limitless variability, and thus in the, we don’t think overly euphoric words of Schlüter, with the Mannesmann-Haus Peter Behrens, “perfected the open floor plan system and the possibility of free room division”16

The 7m x 3.7m “cell of the body” standardised office unit in the Mannesmann-Haus, Düsseldorf by Peter Behrens

The principle of simplicity Peter Behrens applied to the exterior and the floor plan was continued throughout the interior design; whereby Behrens was very clear to differentiate between simple and cheap, noting that “every superfluous luxury has been avoided. However nowhere are off-the-shelf goods used, but for all details, such as linoleum, lincrusta, light fixtures and other metalwork, the form most suitable for the respective purpose has been manufactured.”17

And as befits Behrens the Gesamtkünstler it was he himself who defined “the form most suitable for the respective purpose”, and consequently he himself who was responsible for the furniture, fixtures and fittings within the building.18 And while today many of the original fixtures and fittings remain, the furniture is, alas, no more, for as Horst A. Wessel notes, “when the British military administration withdrew in 1946, the building – with the exception of the telephone exchange – was completely gutted”. And the British Army tried, unsuccessfully, to take that telephone exchange as well. 19

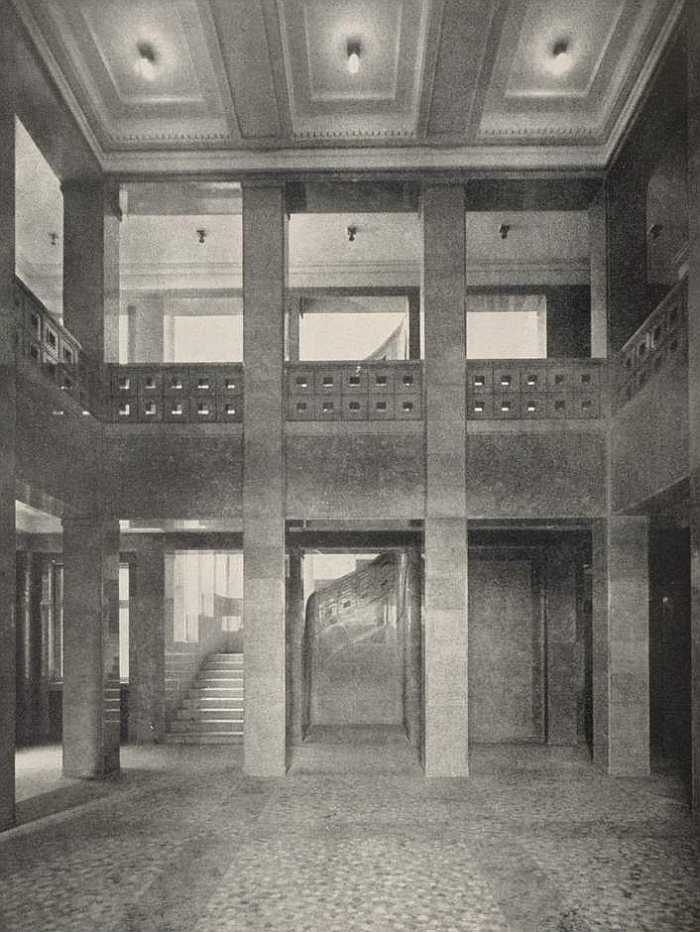

The only slight indulgence was/is to be found in the vestibule, that location where important guests were greeted and which was thus more luxurious, or at least a little; Behrens noting that “here, too, all pomp through rich decoration or architectural ornamentation is intentionally avoided, and a more sophisticated character sought alone through the material”.20

Material such as the marble used for the vestibule staircase; a marble staircase which, according to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, had been his contribution to the Mannesmann-Haus21, for lest we forget, not only was Le Corbusier in Behrens’ employ in the early years of the 20th century, but also Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies.

Mies also recalling that Le Corbusier was involved in the development of the facade, while Gropius drew the floor plans.22 And while in no way questioning Mies’s memory, not only does popular understanding have it that Gropius left Behrens employ in the first half of 1910, and thus arguably before the floor plans would have drawn to any great detail, but Gropius was famously a very poor draughtsman, and thus would have been an odd choice for the floor plans. But we weren’t there, Mies was; and Gropius would later work on standardised, modular, architecture systems that can be understood as a further development of the repeating cells of the Mannesmann-Haus. That Le Corbusier worked on the facade is, certainly in context of chronology, more probable, and if so would, arguably, have been his first experience of not only a large public building, a large complex construction, but his first experience of working with a metal skeleton frame construction. While Mies’s contribution to the staircase reminds us that he came from a masonry background, that he was articulate at expressing himself in stone and stucco long before any other material, and certainly long before he became known for steel skeleton constructions. Of which again the Mannesmann-Haus was arguably his first practical experience.

And thus aside from its place in office building history, the Mannesmann-Haus is also, at least potentially, an interesting station in the early careers of three young architects who would in their own ways contribute to wider architectural history.

The vestibule with marble staircase by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (Photo from Dekorative Kunst, 1917, courtesy www.digitale-sammlungen.de CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In the course of the 1930s Mannesmann’s continuing growth meant that even with all its inherent variability Behrens’ building was too small for contemporary needs, and an extension was commissioned; an extension Behrens had foreseen and planned for, leaving the facade on the rear of the building23, if one so will the facade facing the Düssel rather than the one facing the Rhein, in brick and without the rusticated pedestal, so that an extension could be attached with a minimum of complication. And an extension that Hans Väth, at that time Head of the Mannesmann Construction Department, realised in 1937-38 in keeping with Behrens’s original concept, and also in close contact and cooperation with Peter Behrens. And that as one of Behrens’ last completed projects, Peter Behrens passing away in Berlin on February 27th 1940, aged 71.

Following its post-War tenure as a British army base, and source of free furniture, the Mannesmann-Haus was briefly used by the newly formed Nordrhein-Westfalen regional government before being returned to Mannesmann in 1953 where it continued in its primary function until, as noted above, December 2012. Since when it has largely stood empty, save a brief period as emergency refugee accommodation.

In November 2019 the Mannesmann-Haus was officially confirmed as the future home of the new Haus der Geschichte Nordrhein-Westfalen, Museum of the History of Nordrhein-Westfalen; which on the one hand is most appropriate as it is a building very closely related to the (hi)story of Nordrhein-Westfalen, and on the other underscores the variability inherent in its design. A variability arguably more extreme than Peter Behrens had in mind, but one that neatly reflects Mart Stam’s position that “a building, built today as a bank, should be able to be used tomorrow as an office building, department store or hotel”24; and in doing so tending to further underscore Behrens role as an important intermediary on the way to Functionalist Modernism.

And also allows the Mannesmann-Haus to serve as a not uninteresting object in discussions on the evolving functionality of buildings, for all those buildings considered important works, be that historically or in the oeuvre of a given architect, and which thus are awarded listed building protection status; and for all considerations and discussions on how far listed building protection can or should restrict any given buildings’ evolution. Questions of what is being protected? And why?

For our part we only hope that the architects responsible for the transformation of the Mannesmann-Haus into the Haus der Geschichte Nordrhein-Westfalen don’t lose sight of the variability Behrens so effortlessly, logically, and deliberately, incorporated into the work, and allow it continue to develop and evolve, wherever its future journey may take it.

In the 1950s Behrens Mannesmann-Haus received a new neighbour, the Mannesmann-Hochhaus by Paul Schneider-Esleben, the first steel skeleton skyscraper in Germany, a construction based on principles developed by Mies van der Rohe, with whom Schneider-Esleben consulted during the planning process, and a construction employing Mannesmann steel tubes as the bones of its skeleton; while Behrens’ work was built on the profits of Mannesmann’s production, Schneider-Esleben’s was built, literally, on those products. And thus making that particular stretch of the Rheinufer a not uninteresting architectural historical site, and that, as discussed in our Tour de l’architecture de Düsseldorf, one of many architecturally interesting sites in Düsseldorf.

If amongst which the Mannesmann-Haus is one of the more interesting, not only as a work that helps one approach a better understanding of Peter Behrens and his place in the (hi)story of architecture and design, nor only as a work that helps one approach a better understanding of how Art Nouveau flowed into Functionalist Modernism, but for all as a work which allows a better understanding of the development and (hi)story of the commercial office building. In his December 1912 address Behrens spoke of a how with the Mannesmann-Haus he understood, at least part of, his job, as exploring “the character of an office building, and with all intent to strive for a Typus“;25 a standard, an archetype, a model. And arguably through his near limitlessly variable floor plan and the thereby achieved embodiment of the understanding that a commercial office building isn’t a static construction but rather a framework in continual flux, and also through his considerations on, and realisation of, a meaningful, natural, internal illumination, and his conclusion that “it is not alone the amount of light that is important, but also the distribution of the light”26, Peter Behrens achieved not just a Typus, but an evolved theoretical understanding of what a large commercial office building should and must be. An understanding whose expression today may be achieved by somewhat different means, but is essentially unchanged.

And thus the Mannesmann-Haus stands not only as an important work in Peter Behrens’ oeuvre, nor only as a charming and engaging early 20th century interpretation of cubic monumentality, but for all stands quietly, if conspicuously, proudly, if not conceitedly, on the banks of the Rhein as a genuine milestone in office building design.

The Mannesmann-Haus by Peter Behrens (l) and the Mannesmann-Hochhaus by Paul Schneider-Esleben as viewed from the Rheinkniebrücke

1. Peter Behrens, Zur Einweihung des Neubaues des Verwaltungsgebäudes der Mannesmannröhren-Werke in Düsseldorf, 10th December 1912, reprinted in Hartmut Frank & Karin Lelonek [Eds.], Peter Behrens, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Gespräche 1900 – 1938, Dölling und Galitz, Hamburg, 2015 pages 431 – 443

2. Horst A. Wessel, Kontinuität im Wandel. 100 Jahre Mannesmann AG 1890-1990, Mannesmann AG, Düsseldorf 1990 page 154

3. The exact date is lost in the mists of time, but as Brigitte Schlüter notes the purchase of the site was completed on January 7th 1910 and on February 8th 1910 Richard Hultsch wrote to the Düsseldorf building authorities requesting clarification on some technical points, see Brigitte Schlüter, Verwaltungsbauten der Rheinsich-Westfälischen Stahindustrie 1900 – 1930 PhD Thesis, Rheinischen Friedrch-Wilhelms Universität zu Bonn, 1991 page 124 – 125. And so one must assume that the competition was started in January 1910. But could have been February.

4. Although oft quoted that five architects participated, there is by all accounts no list of the five. That Alfred Fischer participated can be gleaned from Otto Albert Schneider, Arbeiten des Architekten Regierungsbaumeister Alfred Fischer, Essen, Der Industriebau Vol. 4, 1913, pages 77-95; for Richard Hultsch see Brigitte Schlüter, Verwaltungsbauten der Rheinsich-Westfälischen Stahindustrie 1900 – 1930 PhD Thesis, Rheinischen Friedrch-Wilhelms Universität zu Bonn, 1991 page 125; and for Wilhelm Kreis see Katalog der Grossen Berliner Kunstausstellung 1911, page 63, whereby it is not 100% certain that the listed project is the Mannesmann HQ, but it’s very unlikely to have been anything else.

5. Horst A. Wessel, Kontinuität im Wandel. 100 Jahre Mannesmann AG 1890-1990, Mannesmann AG, Düsseldorf 1990 page 156

6. One must also note that Behrens had no formal training as an architect, he was very much an autodidact. And must also note that parallel to the Mannesmann project Behrens was also commissioned with and developed the Imperial German Embassy in St Petersburg, an arguably more representative and complex building. His star was very much in ascendency in the early 20th century

7. Peter Behrens, Zur Einweihung des Neubaues des Verwaltungsgebäudes der Mannesmannröhren-Werke in Düsseldorf, 10th December 1912, reprinted in Hartmut Frank & Karin Lelonek [Eds.], Peter Behrens, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Gespräche 1900 – 1938, Dölling und Galitz, Hamburg, 2015 pages 431 – 443

9. see e.g. Le Corbusier und Zurich, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, 2020

10. Peter Behrens, Zur Einweihung des Neubaues des Verwaltungsgebäudes der Mannesmannröhren-Werke in Düsseldorf, 10th December 1912, reprinted in Hartmut Frank & Karin Lelonek [Eds.], Peter Behrens, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Gespräche 1900 – 1938, Dölling und Galitz, Hamburg, 2015 pages 431 – 443

11. ibid We have no indication if and/or how often such happened, how often the office space was actually changed or indeed how easy, practical, a process it was in reality; however, it is the development and expression of the principle that is more interesting. Would still be good to know.

12. Louis H. Sullivan “The tall office building artistically considered”, in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, Philadelphia, March 1896

13. Peter Behrens, Zur Einweihung des Neubaues des Verwaltungsgebäudes der Mannesmannröhren-Werke in Düsseldorf, 10th December 1912, reprinted in Hartmut Frank & Karin Lelonek [Eds.], Peter Behrens, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Gespräche 1900 – 1938, Dölling und Galitz, Hamburg, 2015 pages 431 – 443

14.Our #officetour is an ongoing process and if/when in its course we meet earlier examples, we’ll be sure to set a milestone for them. But if we do find others, we can’t imagine they’ll detract from the significance and charm of the Mannesmann-Haus

15. Buildings such as the 1885/1886 Dovenhof which Jan Lubitz describes a “a prototype for all subsequent Hamburg Kontorhäuser”, see Jan Lubitz, Von der Kaufmannsstadt zur Handelsmetropole – Entwicklung des Hamburger Kontorhauses von 1886–1914 in Stadtentwicklung zur Moderne. Die Entstehung großstädtischer Hafen- und Bürohausquartiere, ICOMOS – Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees Volume 54, 2012. And we will return to the Kontorhaus. And it is important to note that Behrens employed such in context of a developing, single-user, office building, rather than to aid the renting of space in a multi-user Kontorhaus.

16. Brigitte Schlüter, Verwaltungsbauten der Rheinsich-Westfälischen Stahindustrie 1900 – 1930 PhD Thesis, Rheinischen Friedrch-Wilhelms Universität zu Bonn, 1991 page 165

17. Peter Behrens, Zur Einweihung des Neubaues des Verwaltungsgebäudes der Mannesmannröhren-Werke in Düsseldorf, 10th December 1912, reprinted in Hartmut Frank & Karin Lelonek [Eds.], Peter Behrens, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Gespräche 1900 – 1938, Dölling und Galitz, Hamburg, 2015 pages 431 – 443

18. In terms of the furniture it isn’t 100% clear if Behrens’ designed all the furniture or just selected pieces. Horst A. Wessel, Die Mannesmann-Verwaltung am Düsseldorfer Rheinufer, in Düsseldorfer Jahrbuch 84, 2014, page 250-251 implies that he designed all, while Fritz Hoeber notes that Behrens “only designed the most outstanding spaces, some management offices and conference rooms, etc.” see Peter Behrens Verwaltungsgebäude der Mannesmann-Röhren-Werke in Düsseldorf am Rhein, Kunstgewerbeblatt, Vol 24, 1913, page 189. Given the wide variety of furniture objects depicted and the relatively short planning and building phase it would have been a major effort to have designed, and produced, everything, but not impossible….. and maybe a young Mies and a young Le Corbusier helped….Which, yes, is a tantalising thought….

19. Horst A. Wessel, Die Mannesmann-Verwaltung am Düsseldorfer Rheinufer, in Düsseldorfer Jahrbuch 84, 2014, page 251. And all which poses the question how many relatives of Second World War British military personnel are still using Mannesmann furniture? Potentially unrecorded Behrens, Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier furniture?

20. Peter Behrens, Zur Einweihung des Neubaues des Verwaltungsgebäudes der Mannesmannröhren-Werke in Düsseldorf, 10th December 1912, reprinted in Hartmut Frank & Karin Lelonek [Eds.], Peter Behrens, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Gespräche 1900 – 1938, Dölling und Galitz, Hamburg, 2015 pages 431 – 443

21. Letter from Paul Schneider-Esleben to Dr Egon Overbeck, 25.6.1976, Mannesmann Archiv, see Horst A. Wessel, Die Mannesmann-Verwaltung am Düsseldorfer Rheinufer, in Düsseldorfer Jahrbuch 84, 2014, page 246

23. The question of the “front” and “rear” is subjective, while the Rhein side was the representative main entry, and thus the front, for senior management and important guests, most employs entered through the doors on the Düssel side, which thus for them was the front

24. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, i10 International Revue, 1/2 1927

25. Peter Behrens, Zur Einweihung des Neubaues des Verwaltungsgebäudes der Mannesmannröhren-Werke in Düsseldorf, 10th December 1912, reprinted in Hartmut Frank & Karin Lelonek [Eds.], Peter Behrens, Zeitloses und Zeitbewegtes: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Gespräche 1900 – 1938, Dölling und Galitz, Hamburg, 2015 pages 431 – 443

Tagged with: #officetour, Düsseldorf, Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Mannesmann, Mannesmann-Haus, milestones, Peter Behrens, Walter Gropius