5 New Architecture & Design Exhibitions for December 2020

To paraphrase the Propellerheads, this is just a little bit of a blog post repeating…

For much as with our November 2020 exhibition recommendations, so some of our December 2020 exhibition recommendations won’t be opening. Or at least not in December 2020.

But then as now are in still in our list.

On the one hand because they will open, and is an important part of any pleasure not the expectation and anticipation?

And on the other hand, because that which makes an exhibition recommendable in advance of its opening, that which makes its anticipation and expectation so pleasurable, is that it promises to present a rarely explored subject and/or promises to explore a regularly presented subject from a new and/or fresh and/or deeper perspective. And thus a recommendable exhibition is also a nudge that there may be more to learn and understand about architecture and design than you were aware of. And thus a stimulus for your own research. And what better season than winter for that research?

Our five recommendations/stimuli/nudges for December 2020 can be found in Berlin, Vienna, Helsinki, Rome and St Petersburg.

And as ever in these times, if you do feel comfortable visiting any museum, please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious….

“The Early Years. Mart Stam, the Institute and the Collection for Industrial Design” at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin, Germany

On May 1st 1950 the Dutch architect Mart Stam took up the post of Rector of the Hochschule für angewandte Kunst in East Berlin, and thus an important position in both the post-War rebuilding of eastern Germany and also the development of the freshly established East German state. A rebuilding and development to which Stam sought to contribute not only through training a first generation of East German artists, applied artists and designers, but more directly through the Institut für Industrielle Gestaltung, Institute for Industrial Design: an institute proposed before Stam’s arrival in East Berlin, but which was developed according to Stam’s plan; an institute established to cooperate with industry in the development of objects of daily use of all genres: an institute amongst whose early staff one counted the likes of Marianne Brandt, Albert Krause and Max Gebhard.

And an institute which began its work against the escalation of the so-called Formalism Debate in East Germany. A debate oft discussed in these dispatches and which, and summarising more than is advisable, saw the East German authorities prioritise heavily decorated, handmade, objects over mass-produced, formally reduced, objects. And a debate which thus very naturally set a Mart Stam at odds with the East German authorities. And while Stam resisted and fought his corner, ultimately the East German authorities prevailed: in September 1952 Stam was suspended from his Rectorship and shortly afterwards departed East Germany.

With the exhibition The Early Years the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge Berlin, promise not only to present works realised by the Institut für Industrielle Gestaltung during the two short years of Stam’s leadership, but for all to use those works as the basis for an exploration of the hows, why and wherefores of the contradicting positions in early 1950s East Germany. And in doing so should not only allow for considered reflection on the early years of industrial design in East Germany, nor only on the influence of politics on design, nor nor only only on the what if Stam hadn’t been forced out? But also on an important, yet inadequately popularly understood, moment in the biography and career of Mart Stam.

The Early Years. Mart Stam, the Institute and the Collection for Industrial Design was scheduled to open at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Oranienstraße 25, 10999 Berlin on December 10th, however on account of local Corona regulations won’t. But will hopefully open soon. Please check the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge website for information and updates.

“The Early Years. Mart Stam, the Institute and the Collection for Industrial Design” at the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin (photo Franziska Adebahr, courtesy Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge)

“Adolf Loos: Private Houses” at the MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, Austria

Aside from new formal expressions a further important aspect of the developments of and in architecture during the first decades of the 20th century was an increased focus on, and awareness of, the provision of housing for the working classes. That whereas throughout history architecture had, all but exclusively, concentrated on developing commissions for wealthy clients, in the early 20th century, and certainly after the Great War, architecture’s attention turned ever more to the provision of homes for those who couldn’t afford a home. Far less an architect to design one.

A state of affairs that can be particularly satisfyingly followed and explored in the oeuvre of the Austrian architect Adolf Loos, an architect who not only raged against ornamentation and tattoos, but who in the 1920s and 1930s developed in parallel housing projects for wealthy clients and public bodies.

Promising a presentation of sketches, models and photographs via which to introduce and discuss both Loos’s public works realised in context of, for example, the Vienesse Siedlerbewegung or the Austrian Werkbund and also his numerous private villa and Landhaus commissions, both realised and unrealised, Private Houses should not only provide for a concise introduction to Adolf Loos’s 1920s and 1930s domestic architecture projects, but for all should enable a comparison between his approach to his private and his public commissions. And in doing so should allow not only for a better understanding of the architecture of Adolf Loos, but also help one approach a more probable understanding of the development of architecture in the first decades of the 20th century.

Adolf Loos: Private Houses is scheduled to open at the MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Stubenring 5, 1010 on Tuesday December 8th and run until Sunday March 14th. Please check the MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst website for more information.

A design for a house for the Siedlung am Heuberg, Vienna by Adolf Loos, 1921, part of Adolf Loos: Private Houses at the MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna (photo © ALBERTINA, Wien, courtesy MAK – Museum für angewandte Kunst)

“The Eye & the Icon” at the Museum of Finnish Architecture, Helsinki, Finland

As noted in context of the exhibition The Architecture Machine. The Role of Computers in Architecture at the Architekturmuseum der TU München, for all that architecture is about the built environment and creating shells within which we can live, work, learn, convalesce, consume, exercise, et al, architecture is increasingly also something consumed through media. Not just the Storytelling by which architects seek to bring the emotive to a not yet realised project, but also the omnipresent and all-pervasive heavily post-produced photos that are de rigueur to announce the completion of any construction. Certainly one of a high profile architect.

But what do such architecture photos actually tell us about a building?

By way of a semester project students at the Aalto University’s Department of Architecture asked just such a question in context of 15 prominent buildings in Helsinki, 15 buildings which at their completion were subject to widespread media coverage, and 15 buildings the students studied in context of their material and functional reality juxtaposed with their media image.

The results of their considerations being presented in the The Eye & the Icon.

And results which should, hopefully, allow for fresh reflections on not only the accuracy of architecture photography, the camera may never lie, but rarely tells the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth; but also on the relevance, value, and consequences of the heavily post-produced photo in the development of popular understandings of architecture. And by extrapolation considerations on whether it is advisable to continue consuming architecture visually via photography, or if a change of diet, or possibly just a variation of diet, wouldn’t be beneficial: for our built environments, functional shells and thus our societies.

The Eye & the Icon is scheduled to open at the Museum of Finnish Architecture, Kasarmikatu 24, 00130 Helsinki on Friday December 11th and run until Sunday January 31st. Please check the Museum of Finnish Architecture website for more information.

“Aldo Rossi. The Architect and the Cities” at MAXXI, Rome, Italy

Born in Milan in 1931 Aldo Rossi studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano and upon his graduation in 1959 took up an editorial post at the architecture magazine Casabella; a publication for whom he had written as a student and which brought him into contact with the group of architects around the then editor Ernesto Nathan Rogers. And an association with Casabella and Rogers that placed the young Rossi at the heart of so-called Neoliberty, that post-War re-flourishing of Italian Art Nouveau as a reaction to the (what was perceived as) heavily dogmatic inter-War Functionalist Modernism.

And a moment in Italian architectural and design (hi)story that, in many regards, was influential in the development of Rossi’s understandings of architecture, not least his use of historical motifs and archetypes, albeit in formally reduced expressions and contemporary materials. An, if one so will, updating of the existing rather than a replacement with the new. Similarly Rossi’s understanding of urban planning was essentially one of a city as a space in continual development and which should be supported in this development rather than forced to undergo the rebuilding and redevelopment of the Modernist Functionalists. Positions and understandings which bequeathed him an important role in the development of Postmodernism.

Although very much a practising architect Aldo Rossi was also an active and prolific educator and theoretician, and these three aspects of Aldo Rossi’s work and contribution to the development of architecture form the pillars on which the MAXXI Rome’s Rossi retrospective stands.

A retrospective which promises not only to provide a fulsome introduction to Aldo Rossi and his oeuvre, but also to allow for reflection on Rossi’s positions and understandings in context of contemporary architecture and urban planning.

Aldo Rossi. The Architect and the Cities was scheduled to open at the MAXXI – Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Via Guido Reni 4A, 00196 Rome on Thursday December 17th, however on account of local Corona regulations almost certainly wont. But will hopefully open soon. Please check the MAXXI website for information and updates.

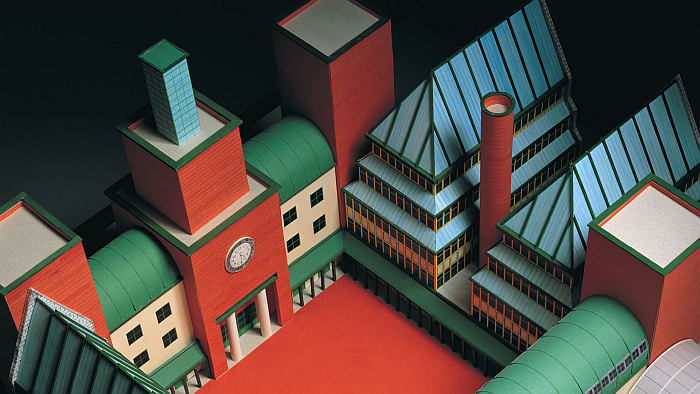

Project model for the UBS administrative building, Lugano, by Aldo Rossi, part of Aldo Rossi. The Architect and the Cities at MAXXI, Rome

“Decorative Minimalism. “The Thaw” in Soviet Porcelain” at The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia

Every Christmas the Hermitage, St Petersburg, present the public a Christmas Present in the form of a very specific showcase, and this years take us, in many regards, back to the start of this post.

The Formalism Debate of the early 1950s that had such far-reaching consequences for Mart Stam, (largely) originated in Stalin’s Russia, was, if one so will, a component of Stalinism; and thus following Stalin’s death in March 1953, and his succession by Nikita Khrushchev, ended as if it had never been and a period popularly known as The Thaw spread over the Soviet Union. Not only a political and social thaw as Khrushchev moved away from the harsher, more repressive, elements of Stalinism, but also a cultural thaw: artists and creatives of all hues being afforded a new liberty, and understanding how to use it.

With Decorative Minimalism the focus, as the title implies, is porcelain, and an exploration of how ceramists, primarily those associated with the Leningrad Lomonosov Porcelain Factory, used the new freedoms of the Khrushchev Thaw to express themselves with a decorative and formal freedom that previously would have been unimaginable. And in doing should not only provide for a succinct introduction to mid-20th century Russian porcelain and its relationship to wider understandings of the period, but, and as with The Early Years, also for reflection on the influence of politics on design.

Not least because following Khrushchev’s 1964 replacement by Leonid Brezhnev The Thaw ended, a more restrictive regime was awoken from its brief slumber: thus those works realised in the decade 1953-1964 represent a very specific snapshot of Russian (hi)story, Russian design (hi)story and the relationships between design and wider realities. Historic and contemporary.

Decorative Minimalism. “The Thaw” in Soviet Porcelain is scheduled to open at The State Hermitage Museum, 2 Palace Square, 191186 St Petersburg on Saturday December 26th and run until Sunday April 4th. Please check The State Hermitage Museum website for more information.

Tagged with: Adolf Loos, Aldo Rossi, Berlin, Decorative Minimalism, Formalism Debate, Helsinki, Hermitage, MAK, Mart Stam, MAXXI, Museum Angewandte Kunst, Rome, Saint Petersburg, The Early Years, The Eye & the Icon, Vienna, Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Wien