In 1950 the Dutch architect and designer Mart Stam told a conference in Leipzig, "when I speak here for a group of individuals active in industry about the problem of industrial design, I do so because I believe that it is necessary for us to concern ourselves in detail with the question of industrial design, and also because I believe that through intensive work and cooperation in this field we can contribute to increasing the cultural quality of our goods."12

With the exhibition The Early Years. Mart Stam, the Institute and the Collection of Industrial Design the Werkbundarchiv - Museum der Dinge Berlin elucidate that Stam did more than simply speak about "the problem of industrial design" in the, then, fledgling East Germany, that Mart Stam wasn't the only person in 1950s East Germany interested in "increasing the cultural quality of our goods", if ideas about how one defined "increasing" and "cultural quality" varied greatly; and in doing so allows insights into the development of industrial design in East Germany......

Whereby it's important to note that industrial design in eastern Germany doesn't start with the constituting of East Germany in 1949. Nor with the arrival of Mart Stam in 1948 in the, not yet, constituted East Germany.

It doesn't. And doesn't.

Much more, on account of institutions such as, for example, Bauhaus or Burg Giebichenstein Halle and also through the innumerable industrial enterprises based in the region who concerned themselves with contemporary materials, contemporary technology, contemporary realities, et al, early 20th century eastern Germany, was one of the principle European motors in the development of production processes, formal expressions, design positions, etc throughout the first third of the 20th century, and thereby an important centre of the early, early years of industrial design as we understand it today.

Then, as so oft in 20th century Europe, came the Second World War, and, and as discussed in context of German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History at the Vitra Design Museum, post-Second World War the freshly constituted East Germany, as with the equally freshly constituted West Germany, had to find their own way forward in context of the design and production of consumer goods of all genres, had to develop their own relationships to industrial design; and that in context of the new political realities caused by the creation of the two Germanys and also of the economic realities within the two Germanys as a consequence of the War years.

As a component of that path finding East Germany's, then still provisional Government, issued a Verordnung, a decree, on March 16th 1950 which included a series of "measures for the development of a progressive democratic culture of the German people and the further improvement of the working and living conditions of the intelligentsia"3, and which included the provision that, ".... a teaching and research institute for industrial design with departments for ceramics, household appliances, furniture, and textiles is to be established at the Hochschule [für angewandte Kunst Berlin]"4, and that, if one so will, as an intermediary between the college and industry, by way of making the college a partner for East German industry in terms of developing meaningful forms for industrial production and relevant to the needs and demands of contemporary society.

On May 1st 1950, Mart Stam took up the post of Rector at said Hochschule für angewandte Kunst Berlin and thereby also the responsibility for the establishment of said Institut für industrielle Gestaltung, Institute for Industrial Design. An undertaking he approached with great gusto, noting in his draft proposal from August 1950 that such an institute was "necessary and possible": the later because, "no longer profit, but what is socially necessary and what is economically and technically possible are the basis and starting point of our production"; the former owing to fact that the attempts by industry to develop new forms and new models for the new State were, "inadequately and insufficiently based on well-founded evidence and knowledge, this work is only carried out in isolation, sporadically, randomly and incoherently", and that East Germany was in urgent need of "coordinated design and development work with the involvement and widest use of the best and most progressive forces".5

Positions that Stam didn't arrive at exclusively in context of establishing the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung, for, and lest we forget, it wasn't the first time in the, then, fledgling, East Germany Mart Stam had enthusiastically sought to unite academic research and industry, had enthusiastically sought a "coordinated design and development" for objects of daily use and thereby an "increasing [of] the cultural quality of our goods".

As previously discussed, Mart Stam had originally arrived in East Germany in July 1948 to take up the position of Rector at the not yet merged, but soon to be merged, Akademie der Bildenden Künste Dresden & Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden, a tenure on the Elbe which ended, let's say, acrimoniously. But which before it did saw Stam establish the so-called Produktionsausschuß, Production Committee, which cooperated with, certainly sought to establish cooperations with, industry, and realised, amongst other projects, furniture for student flats in a cooperation with the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau, textile patterns for a wide range of local manufacturers, and a wall lamp by Stam based on a 1920s, Neues Frankfurt era, metal lamp design by Stam, and realised by IKA Beleuchtungskörper Dresden in stoneware.6

Yet despite the, relative, success Stam and the Produktionsausschuß enjoyed, it was a platform but informally integrated into the college's structure and with no official standing outwith the college.

In Berlin with the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung Stam had a much more stable platform, an official mandate, for the "design and development work" in context of industrial production he felt was so important, necessary and possible.

Or at least very, very, briefly had a more stable platform and official mandate. For shortly after his arrival in Berlin the so-called Formalism Debate erupted, a debate which, as previously discussed in these dispatches, and as ever generalising more than is advisable, saw East Germany's ruling SED position itself in favour of what it considered the continuation of a perceived cultural heritage based on the decorative and the handcrafted rather than the reduced and the industrial, and for all saw the SED position itself firmly against "so-called avant-gardists (expressionism, constructivism, abstract art, Bauhaus style, surrealism, etc.)"7 i.e against the likes of Mart Stam. An eruption and positioning largely originating in attempts to define an East German identity separate and distinct from (and better than) imperialist West Germany; an eruption and positioning which saw Stam's tenure in Berlin end every bit as acrimoniously as that in Dresden, if this time the blame lay far less on Stam than it unquestionably had in Dresden; and an eruption and positioning which saw Stam leave the DDR on January 1st 1953 and, in many regards, sink into anonymity. A statement we believe one can make when one considers Mart Stam's position and status in international architecture and design after 1952. Ridiculous as that may appear to be.

And thus while 1948 to 1952 were early years for industrial design in East Germany, they were also swansong years for the career of Mart Stam. If years in which, through his varied activities in Dresden and Berlin, he was, arguably, able to more elegantly and directly than at any other point in his career, explain what he understood in context of relationships between users and their objects of daily use, on the social and cultural relevance of objects of daily use, and for all of the necessity of industrial production, "the problem of industrial design", and why in the early 1950s there was a necessity "to concern ourselves in detail with the question of industrial design".

Questions and answers others would approach and provide following Stam's unhappy departure. Questions and answers other would approach and provide throughout the 1950s by way of developing industrial design in East Germany's early years.

And thus with the scene set, we return to the Werkbundarchiv - Museum der Dinge Berlin.

As an exhibition The Early Years. Mart Stam, the Institute and the Collection of Industrial Design opens, as with Mart Stam's East German biography, in Dresden with Stam's aforementioned wall lamp, and also the 1951 poster/brochure, Das Beste für den Werktätigen, The best for the Workers, featuring projects by students at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden; a poster/brochure whose title underscores the extremely political context in which the production of consumer goods stood in early 1950s East Germany, a context and focus on the "Workers" that would soon become even more politicised; and a poster/brochure in whose openly opining that the objects of daily use "can only be produced by industry in the appropriate quantity and quality. The handcrafts, also the so-called applied arts, are, in our situation of mass demand, impractical and unfeasible", indicates that at the time of its publication the Formalism Debate was still but bubbling away in the background, was still to erupt on the public stage.8

And while many of the projects presented in Das Beste für den Werktätigen had been developed during Stam's tenure in Dresden, by the time it was published Stam had acrimoniously departed Dresden and was enthusiastically developing the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung in Berlin; and that in cooperation with many of the "best and most progressive forces" early 1950s East Germany had to offer, with creatives of various hues who formed the core of the early years of the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung, creatives who in various contexts contributed fundamentally to the early (hi)story of industrial design in East Germany. And creatives responsible for the majority of the projects presented in The Early Years.

For despite Stam's (near) omnipresence in The Early Years, his representation in some context or other in (near) every object on show, Stam's work itself is barely present; much more Mart Stam is, if one will, employed as a moment in the (hi)story of industrial design in East Germany around which the exhibition's narrative is structured, is employed as a connecting element that allows the exhibition's narrative to be freely woven by others; others such as, and amongts may more, Albert Krause, Max Gebhard or Margarete Jahny, the latter whose representation in The Early Years is of a scale that she could justifiably be a sub-title. Or justifiably given her own solo exhibition. Which, yes, would be the more preferable option. 2023 would be most appropriate. But we digress.....

Amongst the many, many, works by Jahny on show in The Early Years one finds a ca. 1951 sintolan, semi-porcelain, coffee/cocoa service intended for use in Kindergartens, which she developed as a student project in Dresden, and which features in Das Beste für den Werktätigen; and also a stoneware stacking coffee service Jahny likewise developed as a student in Dresden, this time during Mart Stam's tenure, and which was subsequently reworked at the Berlin Institute by Albert Krause.

And a late 1940s stacking coffee service which not only helps underscore the importance of Stam's brief tenure in Dresden to the early years of the Institut in Berlin, that that which he began in Dresden he very much continued in Berlin, but which also deftly brings Marianne Brandt into the narrative; Stam having appointed Brandt to the teaching staff in Dresden, in which context she supervised the development of Jahny's stacking coffee service, before she followed Stam to Berlin, and subsequently departed in the wake of Stam's departure.

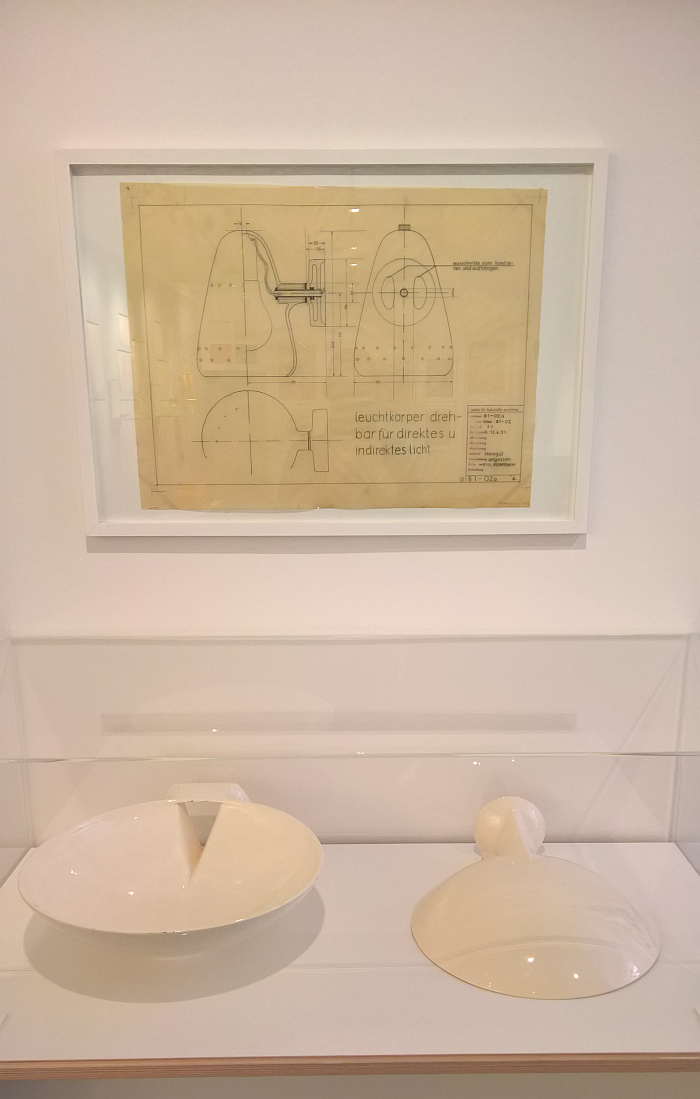

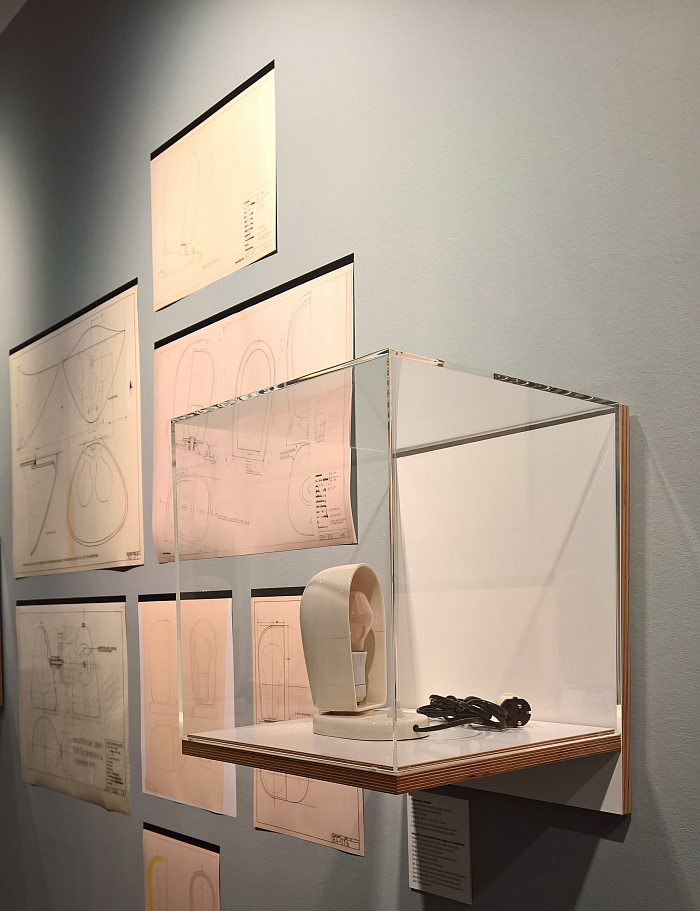

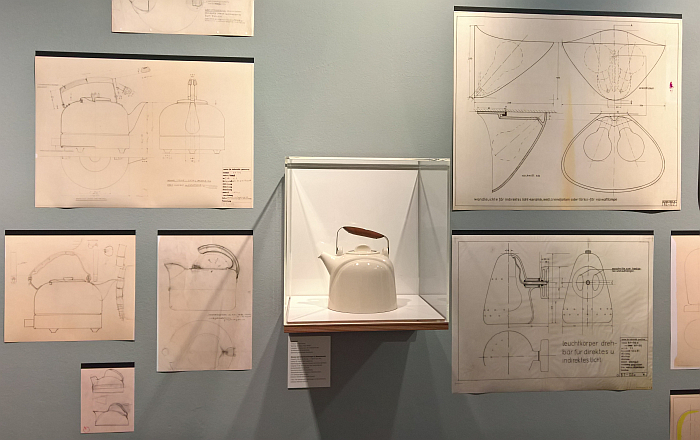

Marianne Brandt's more direct contribution to the early years of industrial design in East Germany being documented by, and amongst other projects, four textile designs which remind us all that before she became known as a 3D artist Marianne Brandt trained, and worked for several years, as a 2D artist, and also by a deliciously joyous stoneware lamp by Brandt and Krause from 1950/51: a work in which the shade revolves around the bulb to control and direct the light, and that a good decade and a half before Vico Magistretti's Eclisse for Artemide; a work which refers, in certain degrees, to some of her 1930s designs for Ruppelwerk Gotha; a work which could sit very comfortably alongside many of the lamp designs Wilhelm Wagenfeld developed in 1950s West Germany for the likes of Lindner or Brunnquell; a work which contrasts with the complaints of a Marcel Breuer over the quality of lamp design in late 1940s America, Breuer commenting in ca. 1949 that "no other details of home furnishings is so sidetracked and backward as the lighting instruments of our surroundings"9, he should have phoned the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung; a rational, communicative and intuitive work which is every bit a formal joy as, we suspect, it is a functional joy; a work that caused us to Whoop Whoop with delight every time we passed it.

And work that posses the question, what if the Formalism Debate hadn't, effectively, forced Marianne Brandt into an early retirement? As oft noted, post-War Marianne Brandt still had a lot to offer, had a lot to contribute. But wasn't given the chance after 1952.10

And which leads naturally on to that other question, what if the Formalism Debate hadn't seen Mart Stam leave the DDR, what if he had stayed and led the Institut throughout the 1950s and 1960s?

Which isn't to say that nothing good was designed in the DDR from 1953 onwards, it was. It definitely, definitely, was.

Is to say that The Early Years is not only an exploration of the early years of industrial design in East Germany, but also a reminder of what the, then, fledgling, DDR lost in design talent, in experienced design talent, in its earliest years, and thus, arguably at the moment it needed it most.11

And that, inarguably, through its own idiocy.

Shortly before Mart Stam's enforced departure the Institut was formally decoupled from the Hochschule, re-named, programmatically so, the Institut für angewandte Kunst, Institute for Applied Art, and was, effectively, placed directly under the control of the State. And was for all placed under the leadership of the artist Walter Heisig who was very much an adherent of the official SED understanding that "increasing the cultural quality of our goods" was to be achieved through ornamentation and decoration, and through traditional craft production, and who consequently took the Institut away from Das Beste für den Werktätigen's position that objects of daily use "can only be produced by industry in the appropriate quantity and quality", took the Institut away from the industrial design and industrial production demanded by Mart Stam. Or as Christa Petroff-Bohne recalls of her brief tenure in the Institut in 1955, "questions concerning the meaning and importance of design for industry as opposed to handcraft [remained] unresolved".12

That "question of industrial design" Mart Stam was the opinion East Germany should "concern ourselves in detail with", that central purpose of his Institut, indeed that central component of Stam's thinking since the 1920s, was, if one so will, declared irrelevant. Was answered in that it was decreed it wasn't a question worthy of an answer.

Or at least by Walter Heisig. And at least officially.

For despite its programmatic change of name, the Institut, and in one of those very typical not-fully-thought-through SED strategies, was still staffed by many of those Stam had appointed to the equally programmatically named Institut für industrielle Gestaltung; and thus, predominately, by designers whose understandings and approaches owed a lot not only to those earliest East German years, to the positions of a Mart Stam or a Marianne Brandt, but to the even earlier inter-War eastern German years that had helped produce a Mart Stam or a Marianne Brandt, and the "so-called avant-gardists (expressionism, constructivism, abstract art, Bauhaus style, surrealism, etc.)" the ruling SED had gotten in such a tizzy about.

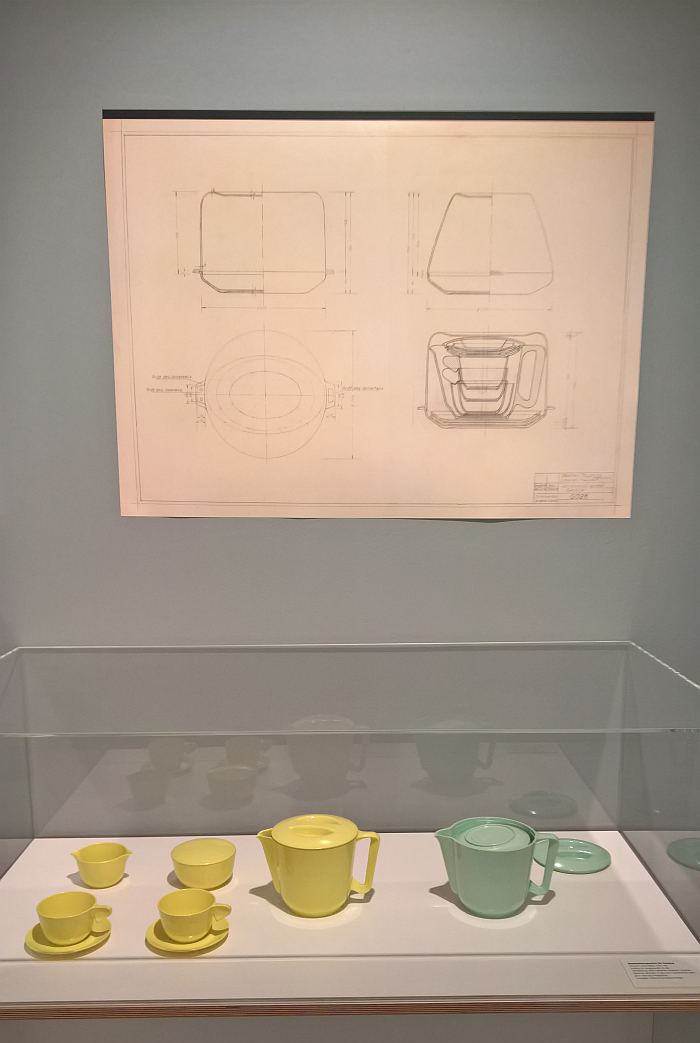

That (many of) the designers at the Institut für angewandte Kunst quietly and diligently busied themselves with ignoring any official positions and maintained true to the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung, and were aided in their doing such by the quiet ebbing of the Formalism Debate following Stalin's death in March 1953, and by the economic realities of 1950s East Germany, being ably demonstrated in The Early Years by works such as, and amongst others, a 1957/58 plastic tea/coffee service for use when camping designed by Hans Merz and by a 1959 aluminium vacuum flask by Margarete Jahny.

The former via the manner in which the cups and accessories space savingly stack inside the pot, a stacking which reminds very much not only of Jahny/Krause's early 1950s stacking coffee service or only of Wagenfeld's 1930s Kubus pressed glass modular stacking storage system for Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke, but for all reminds of Christian Dell's 1930s Sportservice for H. Römmler AG, a plastic travel tea/coffee service where the cups and saucers stack inside the tea/coffee pot; Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke and H. Römmler AG being two of those aforementioned eastern German industrial enterprises who contributed to the development of industrial design in the first third of the 20th century. While, and as we all remember from the Wilhelm Wagenfeld Haus Bremen's exhibition, Stapeln. Ein Prinzip der Moderne, stacking is a Modernist principle.

The latter produced between 1959 and 1964 by VEB Alfi-Fischbach, a criminally short production run for a object which, when one compares it with Jahny's 1951 sintolan Kindergarten coffee/cocoa pot, one understands is formed in context of the material, it couldn't be ceramic, it can only be metal, is an object deliberately designed for its intended industrial production and not as a contextless ideal form; an object whose apparently dilettantishly attached handle, isn't dilettantishly attached, but is attached in a manner to aid production while complementing the form of the flask; is, we'll argue, an object which thus celebrates the fact it is industrially produced; and is an object which shimmers with an unassuming grace and poise that could allow it to be released tomorrow without anyone noticing it has been amongst us for over 60 years. Or should have been amongst us for over 60 years.

Initiated by, and realised in cooperation with, the Stiftung Industrie und Alltagskultur The Early Years makes intelligent use of original technical sketches and objects of varying genres from throughout the 1950s, supported by brochures, posters, letters, documents etc, and further supported by video interviews with Erwin Andrä, Regina Gebhard & Lieselotte Kantner, who were there in the early years, to allow for a readily comprehensible and well paced introduction to and tour through an important moment not only in the (hi)story of design in East Germany but in the (hi)story of East Germany. The two being as they are inextricably linked.

An introduction and tour which is very satisfyingly extended and augmented by the Werkbundarchiv's permanent exhibition display with its myriad objects from early 20th century Germany and from later 20th century East Germany and West Germany and which allow one to approach that presented and discussed in The Early Years in a wider context, in the wider context it should and must be viewed and understood in; including allowing comparisons of what was being defined in 1950s East Germany as gute Form with what, for example, the Deutsche Werkbund were defining as gute Form in 1950s West Germany, and also comparing what was being undertaken in 1950s East Berlin with what was being undertaken in the 1950s at the HfG Ulm, a comparison of the early years of industrial design research and development in West Germany with the early years of industrial design research and development in East Germany.

And a permanent exhibition space which, or at least when we were there, also featured reference to a further Berlin story in the Mart Stam's biography, an earlier, happier, Berlin story in Stam's earlier, happier, biography: as previously noted it was in 1920s Berlin that Stam saw people sitting in their gardens on chairs they had constructed themselves from gas pipes and gas pipe joints. Four-legged chairs whose "closed cube" Stam disliked and which he thus opened into a cantilever chair based on the same materials and construction principle.13 A remake of Stam's original gas pipe chair, that seminal steel tube cantilever, greets visitors to the Werkbundarchiv, while on the wall in the permanent exhibition space hangs a Selbstbau-Stuhl aus Gasrohren, a DIY chair from gas pipes, a work whose origins and date of production is unknown, but is, we imagine, very much of the genre which inspired Stam, certainly of that lineage, and thus one of those myriad anonymous witnesses to the development and (hi)story of furniture design. And which is currently looking for a sponsor.....

Amidst all the focus in The Early Years on the Institut in Berlin, it is important to remember the Institut in Berlin wasn't the only place in East Germany's first decade where "the problem of industrial design" was discussed, where individuals concerned themselves in detail with the question of industrial design or where the Formalism Debate left scars: before the Formalism Debate erupted not just the art college in Dresden but those in Halle, Weimar and Wismar actively concerned themselves with industrial design, before in the course of the Formalism Debate Wismar and Weimar were actively stopped from concerning themselves with such. And after the Formalism Debate had ebbed, industrial considerations continued not only in the Institut in Berlin but in Burg Giebichenstein Halle, and also in the Hochschule fur angewandte Kunst Berlin, that college for which the Institut had originally been conceived as a central component of, and a college where, for example, the aforementioned Christa Petroff-Bohne developed numerous projects in cooperation with East German industry.

The Institut in Berlin does however provide for a particularly pleasingly uncomplicated access to the (hi)story of the early years of industrial design in East Germany; not least through the very close links between the Institut's biography and Mart Stam's biography, each helping you better understand the other not only chronologically, but contentually and contextually, understanding the hows, whys and wherefores as much as the whens, and in doing such allowing the other parts of the narrative to slip effortlessly into place.

A pleasingly uncomplicated access that helps The Early Years allow for better understandings of the technical and material realities that defined the early years of industrial design in East Germany; that, for example, the reason Brandt and Krause's Whoop Whoop inducingly joyous lamp, or Stam's Dresden wall lamp, are in stoneware is, arguably, not a creative decision but one forced by post-War material scarcity. Similarly we assume, we don't know, but strongly assume, that the criminally short run of Jahny's vacuum flask wasn't unrelated to the availability of aluminium, or at least the correct grade and/or form of aluminium, in 1960s DDR.

A pleasingly uncomplicated access that helps The Early Years explain that in 1950s East Germany the decorative, handcrafted existed alongside the reduced, industrial; the former officially demanded by the State, the latter realised by designers whose primary focus wasn't the State, and tacitly allowed to be developed in the guardian of the State's official line by a State who were, inarguably, well aware of the impracticalities of their official line. But hey, what's a totalitarian Dictatorship without Doublethink? And which aside from reflections on East Germany, also allows for reflections on the production of our consumer goods, on the pros and cons of contemporary production, on the pros and cons of contemporary industrial production, on the pros and cons of alternatives.

A pleasingly uncomplicated access that helps The Early Years elucidate through names such as, and amongst many others, Marianne Brandt, Margarete Jahny or Lieselotte Kantner, and Christa Petroff-Bohne who isn't in the exhibition but is very much present, that the first decade of industrial design in East Germany, the early years of industrial design in East Germany, wasn't and weren't exclusively male, they had a very strong, and defining, female component.

A pleasingly uncomplicated access which helps The Early Years underscore why politicians should never, ever, ever, be allowed to dictate cultural expressions, far less define a cultural identity. As previously noted politics and culture always run inter-twinned, always, continually, influence and inform one another, but must, must, remain independent. As must culture and commerce.

And a pleasingly uncomplicated access which helps The Early Years to provide not only for an accessible and entertaining introduction to the early years of industrial design in East Germany, nor only to the nature, context and relevance of Mart Stam's brief sojourn in East Germany, but also of how those early years of industrial design in East Germany fit into and on to the helix of design (hi)story, and thereby allowing for differentiated and more probable understandings of the (hi)story and practice of design in eastern, and East, Germany.

The Early Years. Mart Stam, the Institute and the Collection of Industrial Design is scheduled to run at the Werkbundarchiv - Museum der Dinge, Oranienstraße 25, 10999 Berlin until Monday August 30th

Full details can be found at www.museumderdinge.org/early-years

In addition, and for all who physically can't make it to Berlin, a (German only) catalogue is available which delves deeper into many of the themes and subjects.

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

1Mart Stam, Neue Möglichkeiten auf dem Gebiete der industriellen Gestaltung, reprinted in Hildtrud Ebert, Drei Kapitel Weißensee, Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee, Berlin 1996 page 269ff .... According to Heinz Hirdina the text was a speech Stam was supposed to hold at a conference in Leipzig on 30.08.1950, but, for an unexplained reason, didn't. The speech was however reprinted in the conference documentation, and so stating that he "told a conference in Leipzig" isn't 100% true, but is not incorrect, see Heinz Hirdina, Rückwärts zur Avantgarde, vorwärts zur Kunst in in S.D. Sauerbier [Ed.] Zwei Aufbrüche. Symposium der Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee, Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee, Berlin, 1997

2We suspect that rather than "I speak here for a group of individuals" it should be "I speak here to a group of individuals". In Drei Kapitel Weißensee stands "spreche für" but , for us, either that is a misprint or Stam confused für (for) with vor (before/in front of/to) in his text. In context of the speech "spreche für" doesn't make a lot of sense "spreche vor" does, and thus we suspect an error somewhere. Don't know for certain and so have left it as in Drei Kapitel Weißensee.

3Gesetzblatt der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Nr 28, 23. März 1950. Available via https://www.bundesarchiv.de/findbuecher/sapmo/b_gblddr/mets/50_028/index.htm (accessed 04.06.2021) ...... As the Verordnung makes clear the development of the desired society was dependent on the cooperation and interaction of the workers, the farmers and the intelligentsia, those three stakeholders in society. At least in 1950. As of 1952 the DDR became an Arbeiter und Bauernstaat, a workers and farmers state, presumably the intelligentsia were all avant-gardists.......

4ibid §1 (5)

5Mart Stam, Entwurf “Institut für industrielle Gestaltung” August 1950, reprinted in Hildtrud Ebert, Drei Kapitel Weißensee, Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee , Berlin 1996 page 79ff

6Wolfgang Rother, Mart Stam in Dresden, in Rainer Beck & Natalia Kardinar [Eds.] Trotzdem. Neuanfang 1947. Zur Widereröffnung der Akademie der Bildenden Künste Dresden, Phantasos I, Dresden, 1997 page 159. ........ Stef Jacobs, Oeuvrecatalogus, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016 Available via https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.540323 (accessed 04.06.2021) states the producer of the lamp as VEB Steingut Dresden, and given the propensity of East German companies to change their names, VEB Steingut Dresden could also be IKA Beleuchtungskörper Dresden, under the current realities we can't say for sure.

7Zur Frage des Formalismus, Neues Deutschland, February 13th 1951, Nr 36, Page 3 .... Neues Deutschland was the official newspaper of the SED, and as such the words can be considered the SED's

8Das Beste für den Werktätigen, Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden, 1951 ..... Although the text is officially credited to "cand. art Werner Michael, Assistent am Lehrstuhl für industrielle Formgebung", and Mart Stam left Dresden in April 1950, one imagines the text was, at least partly, informed by Mart Stam's positions and time in Dresden. Certainly the part we quoted. Interesting is also the distancing in the text from the more dogmatic, technical understandings of Functionalism and also from standardisation and the call for more responsive, humane solutions that reflect we're all individuals and not machines. And which thus exist very much in context of the wider post-War criticism of the rigidity and harshness of inter-War Functionalist Modernism, and a call for more flexibility and variability. Something Mart Stam had long called for in architecture. And which through the likes of, and amongst many others, a Karl Clauss Dietel or a Rudolf Horn would become increasingly prevalent in design in East Germany.

9Marcel Breuer, Better and smaller lighting. Although an undated text by Breuer, it was presumably, in all probability, written in 1949 in context of his MoMA New York House in the Museum Garden project. Available via https://breuer.syr.edu/xtf/view?docId=mets/3818.mets.xml;query=HUL_067-001;brand=breuer (accessed 04.06.2021)

10Yes, Marianne Brandt turned 60 in 1953 and back then retirement was a serious business. But that doesn't mean she would have retired, if she had been given the opportunity to continue working, to continue designing, which she, effectively, wasn't.

11Here one could also bring in the names of Wilhelm Wagenfeld or Herbert Hirche who both left the DDR in the earliest years, and when not for reasons directly related to the politics and political machinations, then not entirely unrelated.

12Christa Petroff-Bohne, Mein Weg als Formgestalterin in Angelika Petruschat, Jörg Petruschat, Silke Ihden-Rothkirch, Schönheit der Form. die Designerin Christa Petroff-Bohne, form+zweck, Berlin, 2020, page 223.

13Stuhlmuseum Burg Beverungen, Der Kragstuhl/The Cantilever Chair, Alexander Verlag Berlin, 1986, page 91