Eames Lighting Design… Or, A search for light in the Eames Universe…

Wandering aimlessly through the digital Marcel Breuer Archive one afternoon, we stumbled across a letter dated July 25th 1950 from Peter M Fraser, one of Breuer’s employees, to the Eames Office, enquiring about a lighting design by Charles and Ray that Breuer was interested in using in one of his architectural projects, and requesting…

…”a lighting design by Charles and Ray”???

Eames lighting???

Eames furniture ✔ Eames toys ✔ Eames exhibitions ✔ Eames textiles ✔ Eames films ✔ Eames photography ✔

But where is the lighting design in the portfolio of Charles and Ray Eames…?

The best place to start moving towards an answer, we decided, although unsure if it actually was, was the “sparkle-like ceiling light fixture” referred to in Fraser’s letter,1 for that was one Eames lighting design that definitely existed.

When albeit only very briefly. And only very tenuously. And was in all probability not by Charles and Ray.

Known as Galaxy, one presumes on account of its stellar formal associations, the object was, according to Neuhart & Neuhart, designed by Don Albinson2, a former student of Charles’ from Cranbrook Academy of Art, who had assisted Eames and Saarinen on their entry for the 1940 Museum of Modern Art, Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition, and who served as a key member of the Eames Office team from 1946 to 1959, making a notable contribution to the many, many, important projects developed in that most productive and prolific of periods. If a notable contribution that isn’t always noted; and as such Albinson is a designer who helps neatly underscore the anonymity in which most designers work, and the truism that the products of any design studio are invariably a combination of the contributions of all employees at that time, and rarely the work of the studio owners alone. Something that is, we feel, very deserving of further recognition from the design industry, and all studio owners. That Galaxy was designed by Albinson, a statement we see no reason to query, has however only marginal consequences for our search for answers to the questions at hand…

Galaxy made its debut, and as far as we are aware only public appearance, in context of Alexander Girard’s An Exhibition for Modern Living staged at the Detroit Institute of the Arts in the autumn of 1949, an exhibition via which Girard sought to help a wider public “understand more about design – especially in terms of our own time”3, and that via a collection of some 2000 every day objects selected by Girard and his team on the basis of a series of physical, formal and aesthetic criteria4, and also six room installations, one each by Alvar Aalto, Bruno Mathsson, George Nelson, Jens Risom, Florence Knoll & Charles and Ray Eames5. The Eames using theirs to present their new Eames Storage Units, ESU, and also to give the fibreglass La Chaise chaise longue its public premiere, in an installation which Girard notes in the catalogue, is “not conceived of as a special room or section of a house, but rather suggests an attitude towards the space and objects with which one lives”, while the Galaxy lamp, so the catalogue and thus one presumes according to the Eames Office’s description, was “not conceived of as an efficient machine for illumination but for its special sparkly optic sensation.”6

So not, primarily, a lighting design, but a light emitting sculptural feature.

A sculptural understanding reinforced in Charles Eames’ reply to Fraser where we learn Galaxy is/was the most joyous bricolage, being as it was, “essentially of automotive parts and brass tubes of sizes varying from 18″ to 6″ radiated from a central sphere”, a central sphere that was “a wooden croquet ball” which had been “hollowed out to allow room to collect the wires.” Which on the one hand we’d like to see you try to get certified for use in a museum exhibition today, and on the other helps illustrate the experimental and ad-hoc manner in which the Eames Office approached much of their product development; that for all the very clear visions of where they wanted to take a project, and why, the path was generally one of informed improvisation and insightful trial and error, and that more often than not with self-conceived and constructed machines. Much of what the Eames Office were striving for was so new, there was no path to it.

From Charles Eames’ reply we also learn that Fraser’s was one of “quite a few inquiries and requests for the Galaxy” the Eames received but which were all to be equally disappointed, for “it has never been put into production”.

Which does tend to pose the question, why not? For even if it wasn’t primarily presented in Detroit as a lamp, (a) there was interest in it, (b) that interest was likely to remain whether Galaxy was a lamp or an illuminating sculptural feature, while (c) with a little further development it surely could have been both an “efficient machine for illumination” and a “special sparkly optic sensation.” The two aren’t mutually exclusive.

Pat Kirkham notes7 that one possible reason for the lack of a commercial release may have been the formal similarity to Gino Sarfatti’s Fuoco d’Artificio, Firework, a lamp designed by Sarfatti in the late 1930s, which achieved a popular fame in the 1950s, and is widely known today not as Firework but as Sputnik. A name that reminds of Galaxy and in doing so reminds us that the Sputnik was launched in 1957, and that the fascination with all things space is a largely 1960s phenomenon, and thus when the Eames Office developed Galaxy in 1949 space still wasn’t a popular thing; thereby tending to imply that the Eames Office was space-age before space-age was a thing. Not that (in our reading) Kirkham is implying Albinson/Eames Office had directly and deliberately copied Sarfatti, only that there was a formal similarity; and in which context we’d point to a vague formal, and conceptual, similarity to George Nelson’s 1948 Ball Clock8, just much more expansive, and a clock that also featured in An Exhibition for Modern Living. And which led on to a whole series of space related Nelson clocks, several of which are formally highly reminiscent of Galaxy.

But did the Eames really not proceed with the development of the project just because of Fuoco d’Artificio, a work produced in Italy by Arteluce, presumably on account of the War in low numbers, and thus a work that, arguably, would have been only little known, if even known at all, in the America of 1949?

And even if they did, where are the other Eames lighting designs, where are the efficient machines for illumination by Charles and Ray Eames…?

1949 is still a very early stage in the (hi)story of Charles and Ray Eames, where are the Eames lamps?

A question that becomes even more pertinent if we travel further back in the Eames (hi)story

Galaxy, and the Eames Storage Units, by Charles and Ray Eames, as exhibited at An Exhibition for Modern Living, Detroit, 1949

Before Charles and Ray Eames there came Ray Kaiser and Charles Eames; the former an artist trained in the New York of the 1930s, the latter a…. well…. a…. a Charles Eames trained in the America and Mexico of the 1920s and 1930s, but who did briefly study architecture at Washington University, St. Louis. And who before, and possibly while he did, also had a job designing lighting fixtures for St Louis based Edwin F. Guth Company9, a firm who through their numerous inventions, for all new materials and production process, contributed greatly to the development of electric lighting design in early 20th century America. At least technically, for as the 1927 Edwin F. Guth Company catalogue illustrates a goodly majority of their designs in the late 1920s remained firmly in historic, pre-electric, formal expressions; a majority of their designs, but not all, and the catalogue also features more contemporary designs, and for all contemporary understandings of, for example, hygiene and reduction in lighting design. And somewhere on that catalogue’s pages could, just possibly, be hidden, amongst the anonymity, the very first lighting related designs by Charles Eames. And if so, which? The historic or the contemporary?

Much more verifiable pre-War Charles Eames lighting designs can however be found by travelling a little further down the Mississippi from St Louis.

Although Charles never graduated as an architect that didn’t stop him working as one, first in a partnership with Charles Gray and later in one with Robert Walsh, the commissions with Walsh including in 1934 St. Mary’s Church Helena and a year later St. Mary’s Church Paragould, both in eastern Arkansas. The latter featuring Art Deco-esque pendant lamps, and while Charles notes he and Walsh did all the fixtures and fittings for the churches10, the Paragould lamps can’t, as best we can ascertain, be nailed down as Eames. Unlike the globe pendant lamps in St. Mary’s Helena; objects which are so formed that, according to those who have witnessed them, as one approaches the altar one sees but a crescent moon slither of light, and also the small stars cut into the metal body; while on returning from the altar one is bathed in the full glory of the light. One walks through the night to the altar and returns enlightened. A nice little metaphor, the sort of simple allegory that is so important to all religions; and one we ourselves have never experienced, but should we ever be allowed to visit Helena, Arkansas, we will seek out.

St. Mary’s Helena is also important in the Charles Eames biography as it attracted the attention of John and Alice Meyer who subsequently commissioned Eames and Walsh to build a house for them in Huntleigh, Missouri, today a suburb of St Louis, a house which Eames and Walsh appear to have approached with an almost Gesamtkünstler flair, designing most everything, and with Charles designing at least part of the lighting, including ceiling sconces “lined with Japanese rice paper for a subtle lighting effect”11…. yes, rice paper based lighting, but a good decade and a half before Isamu Noguchi would bring Akari to the peoples of America.

The two Arkansas churches also being the projects which first brought Charles Eames to the attention of Eliel Saarinen, and which ultimately saw Saarinen invite Eames to Cranbrook Academy of Art, where in 1940 the Charles and Ray (hi)story begins.

And from where the story of Eames lighting starts to fade; Charles not appearing to have carried his varied practical, artistic and conceptual experiences with lighting design from his early career, through into his later.

Which brings us back to the question why, and that with a little more force than previously, brings us, with a little more force, back to the question where is the Eames lighting design? Where are the Eames lamps?

And brings us back to Marcel Breuer.

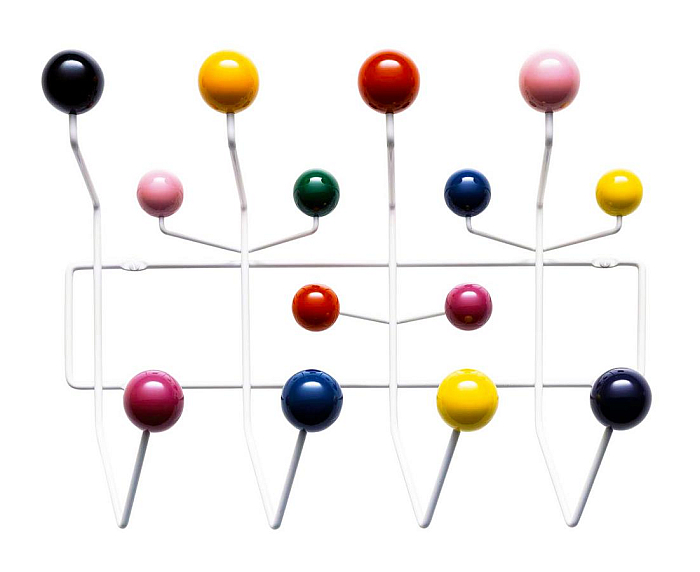

Hang it All by Charles and Ray Eames … an object which, potentially, could have been developed into an Eames lamp…..?

In 1949 the Museum of Modern Art, New York, presented a contemporary housing solution developed by Marcel Breuer, the first in the museum’s House in the Museum Garden series, and a project which courted controversy less on account of the architecture and more on account of the lack of portable lamps within, by which we understand non-fixed table and floor lamps rather than the contemporary understanding of a portable lamp. Breuer claiming that there was nothing available that he considered suitable for a contemporary space, that he “simply didn’t find the problems I had in mind adequately solved by any lamps on the market.”12

Thoughts he continued and expanded upon in an undated document13 in the digital Marcel Breuer Archive in which he notes, “generally speaking probably no other details of home furnishings is so sidetracked and backward as the lighting instruments of our surroundings”, adding that “we have lamps like flowers, swanes [sic] “works of art”, or symbols of chromium philosophie [sic] (poor chromium, reliable, pure, beautiful chromium, what happened with you!)”, which is just the most poetic and heartfelt lament to and of that material with which Breuer had made such a name for himself two and bit decades earlier, and which, one presumes, for Breuer was now reduced to gimmicky streamlining, but we digress… and noting that the contemporary American lamp market was, in effect, a formal, material and aesthetic wasteland of “lamps to be bought – or better, to be sold – with little consideration, if any, of our eyes”.

An opinion on the shortcomings and inadequacies of contemporary lamp design largely echoed by Alexander Girard in context of An Exhibition for Modern Living, also in 1949, and his belief that, “the decorative and clumsy lamps will inevitably be replaced by more efficient and honestly designed equipment.”14

For Marcel Breuer the responsibility for developing those much needed improvements lay with three groups: lighting engineers who he argues devote themselves too little to domestic lighting and for all too much to the physiological and not enough to the psychological of light; manufacturers whose works Breuer considered, “stiff, [occult??], outmoded pieces, still reminding of the old kerosin lamps (but without the latter’s simple charm and efficiency)” and demanding lamps that aren’t historic, kitsch, but “truly attractive in their forms and material”; and “the designers of the so called modern lamps” whose works despite, for Breuer, offering improvements on that which the wider market had to offer, were “still stiff – not flexible enough – its light is too hard, too limiting, its material not sensitive enough for touch, too pretentious, altogether not “human” enough”.

Yet despite harbouring such opinions, Marcel Breuer clearly never felt motivated or called upon to design lamps himself, which poses a further why? And a thought you should hold on to, we’ll need it shortly.

Who did feel motivated and called upon were the Museum of Modern Art, and who in 1950 instigated the competition New Lamps “to encourage the design and production of good portable table and floor lamps employing incandescent bulbs”15, a competition run in conjunction with the Heifetz lighting company, one of the more prominent producers of contemporary lighting at that time, and whose President Yasha Heifetz had been, perhaps understandably, one of the more vocal disputants of Breuer’s claims concerning contemporary American lighting designs16; and a competition which resulted in an exhibition that opened on March 28th 1951, and which presented designs by the likes of Joseph Burnett, Gilbert A. Watrous, Anthony Ingolia and Charles and Ray Eames. Chair designs by Charles and Ray, the exhibition space being populated by “16 chairs, Eames, grey plastic, metal legs”17, and which, one presumes, were the still very new A-shell Eames fibreglass armchairs.

But why no entry in the competition? Where is the Eames entry to New Lamps 1950? Indeed where are all the usual suspects of late 1940s/early 1950s American design, most all the competition winners were students or recent graduates.18 Was American lamp design in 1950, to quote Breuer, “so sidetracked and backward” that established designers dared not approach it?

Yet late 1940s/early 1950s American homes were, according to Marcel Breuer and Alexander Girard, two men we’d tend to trust on these things, very much in need of new lamps, new understandings of lighting, new lighting concepts.

And given that so much of Charles and Ray Eames’ work arose from tackling deficiencies in the design, material, production, affordability, etc of our interiors and furnishings, where are the Eames Lamps?

Or to come back to our original question, where is the lighting design in the portfolio of Charles and Ray Eames…?

The, a, answer could, potentially, be, possibly, found in a very specific late 1940s/early 1950s American home.

“Because most opinion, both profound and light-headed, in terms of post war housing is nothing but speculation in the form of talk and reams of paper”, opined the magazine Arts & Architecture in its January 1945 edition, “it occurs to us it might be a good idea to get down to cases and at least make a beginning in the gathering of that mass of material that must eventually result in what we know as “house – post war””.19 And to that end Arts & Architecture initiated the so-called Case Study House Program in which selected contemporary architects were commissioned/challenged to design houses corresponding to specific realities, for specific cases.

Including Charles Eames. Or more accurately Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen who in 1945 were commissioned to develop Case Houses #8 and #9; #8 being intended “for a married couple both occupied professionally with mechanical experiment and graphic presentation”, which is a very tight brief, a very specific case, and for all a house that was to “aid as background for life and work”.20 And a house which, ultimately, Charles and Ray realised without Saarinen, and which is popularly known today, as the Eames House. Because it is and was.

Standing in Pacific Palisades, on the Los Angeles coast between Santa Monica and Malibu, the Eames House is constructed from and via what Charles refers to as materials and techniques “standard to the building industry, but in many cases not standard to residential architecture”21, essentially off-the shelf materials primarily employed in industrial contexts, and which thus allow for an industrial construction process, and is a work whose highly experimental nature can, we always feel, be best encapsulated in the comments of an unrecorded local planning official when Ray called to thank for them approving the plans for the house: “Well, we didn’t approve a house, we decided it isn’t a house. We don’t know what it is.”22

For Charles and Ray it was home, one they moved into in December 1949 and where they remained for the rest of their lives; and a home which, and as far as we can ascertain, was thoroughly devoid of portable table and floor lamps.23

Much more the illumination of the house is provided by a combination of recessed ceiling lights, wall mounted lighting, and very low, occasionally very, very low, hung pendant lamps; low hung pendant lamps which via their low hanging in many regards take the place of floor and/or table lamps, offer the direct lighting of a table or floor lamp to compliment the more indirect ceiling/wall lighting, without the need for a physical floor and/or table based object. And, also add an extra visual dimension, help disrupt the space and thus serve as an important aid to the avoidance of any monotony or dead air in such a large open volume.

In addition the illumination of the Eames House was largely dependent on candles. “Candles in a variety of candleholders were always placed in every room” note Neuhart & Neuhart24, and in near every photo of the Eames House interior one sees candlesticks, similarly in the 1955 short-film House: After Five Years of Living, ⇓ ⇓ ⇓, candles play a near leading role in many scenes. And candles which remind of the shock many of the Eames’ contemporaries felt when they witnessed an otherwise textbook Functionalist Modernist construction filled with cushions, plants, folk art, found objects and other articles that simply didn’t fit in the idealised uncluttered order of the Functionalist Modernist interior. Similarly candles. Candles come from centuries past. We now have electric light. Candles are an anachronism in a contemporary home. But candles are more than just emitters of light, candles have emotional connections and connotations, have an emotional functionality beyond their technical functionality, and are also, if one so will, related to the psychological function of lighting Breuer felt was missing from contemporary American lighting design; and thus fitted in with, must be considered part of, the humanising of the harsher aspects of more dogmatic understandings of Functionalist Modernism that Aino and Alvar Aalto in many regards initiated and Charles and Ray Eames came to define.

The other leading role in the Eames’ film is taken by the house itself and for all the vast swathes of glass, not least in context of the walls of the 17 feet, 5 meter, high living room. And a glass heavy facade which on the one hand has a role in bedding the house in its surroundings, allowing it to be at one with its environments; but which also allows huge amounts of light to enter, the Eames House is, if one so will, an efficient machine for illumination, is so conceived as to make optimal use of that light so readily available on the Californian coast. And that both technically and emotionally, psychologicaly: the former being particularly neatly demonstrated by the skylight over the stairwell, a space that would otherwise be unremittingly dark; the latter by the continual changes in the light, not only through the passing of the day and the vagaries of the weather, but through the mix of differing glass types and finishes Charles and Ray choose to employ in and for the facade.

And while we can’t all live in glass-walled houses on the ever sunny Californian coast, as John Entenza, Arts & Architecture’s founding editor notes, the house’s “contributions are things to be derived from it rather than things existing precisely within it”25, its not what it is, but what it represents; which reminds us all of Alexander Girard’s comments on the Eames room installation in An Exhibition for Modern Living, and which can lead one to understand the Eames House as “an attitude towards the space and objects with which one lives”, and the lighting concept of the Eames House as an attitude towards space and its illumination. And which if one does, can further lead one to an understanding that the nature and manner of the illumination of the Eames House corresponds to Charles and Ray Eames understandings of domestic lighting design, that the nature and manner of the illumination of the Eames House represents the lighting design in the portfolio of Charles and Ray Eames, not as a physical object, but as a conceptual position.

And that the Eames lamps we’ve been searching for, may be inherited/found candlesticks.

Eames Stools by Charles and Ray Eames … objects which could have been developed into Eames candlesticks…..?

Possibly. We’re hypothesising wildly, and we certainly don’t know for sure. Only Charles and Ray know for sure, and we can sadly no longer ask them about the hows, why and wherefores of the lighting design concept for the Eames House.

But we can return to Marcel Breuer, and to the thought we asked you to hold on to earlier, the why, given his criticism of contemporary lamps, Breuer didn’t design any lamps in the late 1940s/early 1950s.

On the one hand, as Breuer notes, “I am not experienced in the field, and it would take a good deal of research.”26 And lamps are indeed very, very rare in the Breuer portfolio.

An on the other, reading around the controversy of Breuer’s lamp-less MoMA house one comes to the unavoidable impression that it may have been intentionally so, or as Ken Bache questions in Retailing Daily, does the absence of lamps suggest “that Mr Breuer actually shares the opinion of an apparently growing number of modern architects and designers that portable lamps are out of place in modern design?”27 Which is clearly a whole new subject, and one for another day; and an opinion Breuer largely admits to, if that’s the correct phrase, “ideally all the artificial lighting in the home should be completely integrated into the architecture just as the natural lighting is by the window placement”28 he opines, while elsewhere he is recorded as noting that he “likes a room to be well lighted without his being aware of the source of the glow, an effect usually achieved with built-in installations.”29 And thus his MoMA house with its “horizontal, wall-strip indirect fluorescent units and wall “spot” lights”, and lack of portable lamps, represented, or at least approached an approximation of, his ideals; ideals apparently, shared by many of the MoMA visitors, some 77% approving of Breuer’s lamp-less interior.30

Not that Marcel Breuer was completely opposed to floor and table lamps, he wasn’t, had he been he wouldn’t have reflected on the subject to the extent he did; but much more Breuer tended to see floor and table lamps as something to be limited to very specific situations in domestic interiors, and where possible avoided, rather than a standard feature. An opinion he was, apparently, not alone in in the America of 1949.

And thus, arguably, the lamp-less 1949 Eames House can be considered as being reflective of an understanding at that time, of a move away from the table and floor lamps of yore. However, while Breuer didn’t want to see the light sources, the Eames used very visible very low hanging pendants. And candles. And the sun. Used the light sources as components of the interior rather simply as a source of light. And which tends to further underscore that in the lighting design of the Eames House one can read the understandings of Charles and Ray Eames, can read their considerations on and responses to contemporary discussions and discourses on domestic lighting; responses which, we’d argue, underscore their more emotional, human-centred rather than purely functional approach, the latter being an approach in which all artificial light would be “completely integrated into the architecture”. And thereby further underscoring that the term the unrecorded local planning official was looking for to describe the Eames’ construction was: “an attitude.”

¿ And in doing so also allowing us all to approach an understanding of why there are no lamps in the commercial Eames portfolio ?

Not necessarily.

That question, we’d argue, remains open.

Not that there is any reason why Charles and Ray Eames should have designed lamps, and certainly not if they felt the inherited/found candlestick was the better portable lamp; it’s not a decision they need justify.

However, both Alexander Girard and Marcel Breuer reflect a hope that over time lamp design will become better, more appropriate, more meaningful, an opinion, one presumes, that was shared by others, and given the vastness of Charles and Ray Eames’ oeuvre, and the very close relationships of much of that oeuvre with driving forward not just understandings of the objects of our daily use but of driving forward the formal, quality and functional demands of consumers in regard to their objects of daily use, and also given the apparently unhappy state of late 1940s American lighting design, an unhappy state which mirrors the dejection of early 1940s American furniture design, and also also given the realities of 1940s and 1950s American homes, and the fact that a majority of Americans lived in homes where lamps would have been necessary, certainly advisable, Marcel Breuer himself bemoans the fact his living room is in urgent need of a portable lamp to read and work by31, it is, we’d argue, a curious void in the Eames portfolio, and, for us, the question as to why there are no lamps in the commercial Eames portfolio is one worthy of further investigation.

Not least because a search for light in the Eames universe can help illuminate many other under explored and poorly understood corners of not just the Eames universe but of the (hi)story of design…

1. A week before writing to the Eames Fraser also contacted Alexander Girard regarding Galaxy

2. John Neuhart, Marilyn Neuhart & Ray Eames, Eames Design, The work of the office of Charles and Ray Eames, Ernst & Sohn, 1989, page 125

3. Alexander Girard, Catalogue, An exhibition for modern living, Detroit Institute of Arts, 11th September – 20th November 1949 page 5

4. see, Alexander Girard, For Modern Living, New York Times, September 25th 1949 page XX3

5. It goes without saying that room installation was officially listed as Charles Eames alone although Ray was very much involved… As oft noted in these dispatches until the launch of the Lounge Chair in 1956 Ray Eames wasn’t part of the public Eames brand, and that despite Charles noting her contribution at every opportunity. And even after 1956 Ray was often omitted in articles and texts….

6. Alexander Girard, Catalogue, An exhibition for modern living, Detroit Institute of Arts, 11th September – 20th November 1949 page 80-81

7. Pat Kirkham, Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century, Page 437 Footnote 21

8. As previously noted the Ball Clock was possibly designed by George Nelson, or possibly by Irving Harper, or possibly by Richard Buckminster Fuller, or possibly by Isamu Noguchi, or possibly was designed by the whisky…..

9. Virginia Stith, St Louis Oral History Project, Interview with Charles Eames October 13th 1977, reproduced in Daniel Ostroff [Ed] An Eames Anthology, Yale University Press, 2015 366-381 here page 368

11. Eames Demetrios, An Eames primer, Universe Publishing, New York, 2001, page 84

12. New Modern House Opens Without Portable Lamps see also Architect’s Criticism Holds No Fears for Lamp Industry, New Light on Those Portables / Chicago Comments It’s Just Too Bad; Home Lighting Debatted

13. Although undated it was clearly written after the controversy surrounding his MoMA house, because he refers to that. Why he wrote it is unclear, but it could be a draft for an article that was never completed/published

14. Alexander Girard, For Modern Living, New York Times, September 25th 1949 page XX3

15. Museum of Modern Art Press Release 51-312 – 20a https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-Release_325770.pdf pdf!!! (accessed 27.02.2021)

16. see, for example, New Light on Those Portables / Chicago Comments It’s Just Too Bad; Home Lighting Debatted; Architect’s Criticism Holds No Fears for Lamp Industry

17. Museum of Modern Art, New Lamps Master Checklist, https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_master-checklist_325769.pdf pdf!!! (accessed 27.02.2021)

18. As far as we are aware the competition wasn’t limited to students, but it may have been…..

19. Announcement. The Case Study House Program, Art & Architecture, January 1945, page 37

20. Case Study Houses 8 and 9 by Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen, Architects, Art & Architecture, December 1945, page 43

21. Case Study House for 1949. Designed by Charles Eames, Art & Architecture, December 1949, page 29

22. Marilyn Neuhart & John Neuhart, Eames House, Ernst & Sohn, 1994, page 56

23. We can’t be 100% certain that Charles and Ray never had portable lamps in the house, just can’t find any evidence that they ever did. In the studio there are/were spring articulated lamps that clipped onto tables, but such are clearly more a work tool than a lighting object as such. And also in the studio one finds large lamps for film-making/photography, and which remind that for all the popular focus on Eames furniture, film-making/photography were huge components of the Eames oeuvre and disciplines where lighting is more than just technical but also part of the emotion. And so Charles and Ray by necessity thought an awful lot about lighting… just didn’t design any commercial illuminating objects.

24. Marilyn Neuhart & John Neuhart, Eames House, Ernst & Sohn, 1994, page 50

25. Case Study House for 1949. Designed by Charles Eames, Art & Architecture, December 1949, page 27

26. New Modern House Opens Without Portable Lamps

27. Architect’s Criticism Holds No Fears for Lamp Industry

28. New Modern House Opens Without Portable Lamps

30. Museum of Modern Art Press Release 491011 – 72 https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_325655.pdf pdf!!! (accessed 27.02.2021)

Tagged with: Alexander Girard, Charles and Ray Eames, Charles Eames, Don Albinson, eames, eames house, floor lamp, lamps, lighting, Marcel Breuer, pendant lamp, Ray Eames, table lamp