smow Blog Design Calendar: August 5th 1899 – Happy Birthday Mart Stam!

“Wij hebben de nieuwe wereld te scheppen” wrote a, then, 19 year old Mart Stam in 1919.1

“We have to create the new world”

And subsequently spent the following decades developing, explaining and demonstrating his understandings of what that meant……

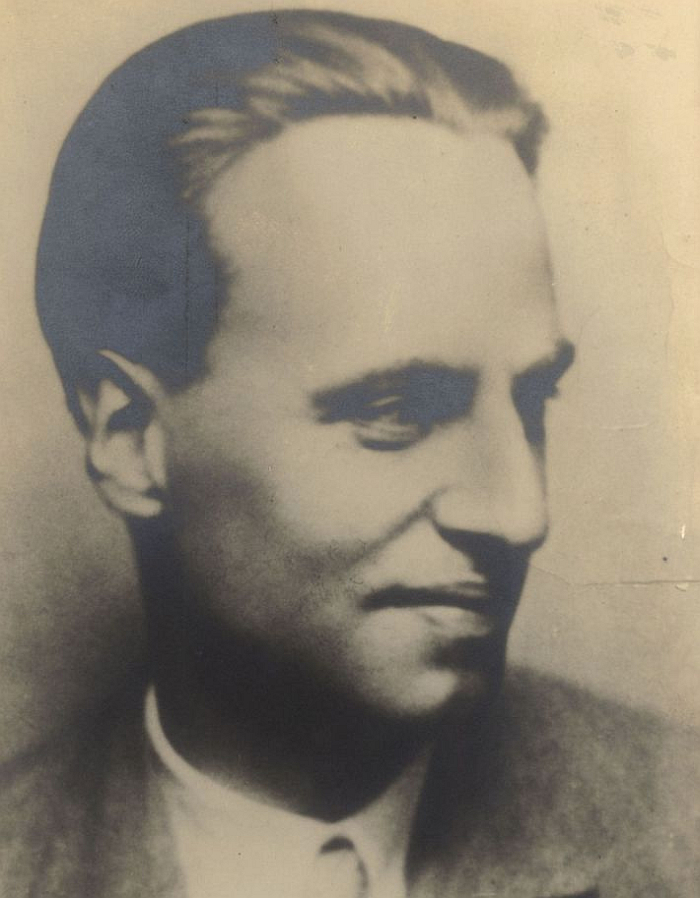

Martinus Adrianus Stam was born on August 5th 1899 in Purmerend, a community to the north of Amsterdam, and which, not uninterestingly, is also the birthplace of Stam’s contemporary J.J.P. Oud.

Following an initial training as a furniture constructor in Purmerend Mart Stam qualified as a draughting teacher at the Rijksnormaalschool voor Tekenonderwijzers, Amsterdam, and, in parallel, undertook a correspondence course in civil engineering at the Polytechnisch Bureau Nederland Arnhem,2 before beginning his architecture career in 1919 as a draughtsman in the offices of Granpré Molière, Verhagen en Kok in Rotterdam, where, and amongst other projects, he worked on the development of the Vreewijk garden village on the south-eastern edge of Rotterdam, and thus an early exposure to the new urban planning thinking of the period.3

Albeit a tenure of employment interrupted when Stam, a life long pacifist, was jailed for ten months in 1920 for refusing to undertake his compulsory military service; and a tenure of employment which ended in 1922 with his move to Berlin, where he worked in the offices of Hans Poelzig und Max Taut, two of the leading figures in the development of inter-War Neue Sachlickeit; Stam assisting the later not only with his (unsuccessful) entry for the Chicago Tribune Tower competition but also with the new headquarters of the Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes in Berlin, a building whose facade is, according to an unproven tradition, the work of Mart Stam.

In addition, during his time in Berlin Stam became friends with the Russian avant-garde painter and architect El Lissitzky, who at that time was serving as a form of cultural attaché for Russia in the Weimar Republic, and who would become an important influence on Stam’s understandings; and also joined the so-called Novembergruppe, a collection of Expressionist/Futurist/Modernist/Functionalist/Dadaist/et al artists and architects, and a connection which saw Stam invited to participate in the International Architecture Exhibition staged as part of the 1923 Bauhaus Ausstellung in Weimar and which saw two projects by the then 24 year old Stam displayed alongside works by German contemporaries such as Erich Mendelsohn, Mies van der Rohe, Adolf Meyer, as well as numerous Dutch contemporaries including Gerrit T. Rietveld and J.J.P. Oud. And thus, and despite the fact that Stam’s works were, allegedly, displayed somewhat unfavourable next to a door,4 helping position Stam in a circle of older, established, architects.

If Stam visited the Weimar exhibition is not recorded, and although one could well imagine he did, as previously noted, the mixture of political turmoil and hyper-inflation of mid-1923 Weimar Republic made it a wonder anyone visited. What is more certain is that the political turmoil, hyper-inflation, and a lack of meaningful work on account of the economic and political realities, saw, forced?, Mart Stam in October 1923 to swap the Weimar Republic for Switzerland.

A view of of Vreewijk Garden Village, Rotterdam, (Photo NAI Collection, “TENT n12” via commons.wikimedia.org)

On his arrival in Switzerland Mart Stam initially worked in Zürich with Karl Moser, the (future) first President of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, before in 1924 swapping the Zürichsee for the Thunersee and the office of Arnold Itten, from where he also undertook several freelance projects, the most notable being, arguably, his, unsuccessful but not uninteresting, entry for the 1924 competition for the new Genève Cornavin railway station.

1924 also seeing Mart Stam along with Hans Schmidt and Emil Roth co-found and co-publish the Neue Bauen orientated magazine ABC – Beiträge zum Bauen, the first in a long list of architecture/interiors/design magazines Stam was to be involved with in the coming decades; a publication which in the course of its four year existence published texts by, and in addition to numerous contributions from its three founders, creatives such as El Lissitzky and Hannes Meyer, the (future) 2nd Bauhaus Director; a publication which devoted itself to the presentation of and discussions on the new understandings of architecture, construction, urban planning, furnishings, society, et al that were developing and evolving at the period; and a publication which in doing so served as an important platform not only for contemporary architecture, but for the protagonists involved.

For all that life in Switzerland appears to have been to Stam’s liking in 1925 he left, officially because good as life was, Switzerland was small, architecturally unadventurous, and Stam saw only little chance of getting work there,5 or certainly work he considered worth having, and thus in October 1925 Stam and his, then, wife Lena, travelled to first Paris where they spent four months submersing themselves in the avant-garde, surrealist, culture that was blossoming at that time on the Seine, and subsequently the relative calm of Purmerend, before in June 1926 moving to Rotterdam where Stam took up a position in the offices of Brinkman and Van der Vlugt, who at that point were involved with the development of the Van Nelle Factory, one of the landmark works of what would become International Modernism, and a work to which Stam unquestionably contributed, if his exact role remains somewhat opaque.

Much more certain is Mart Stam’s contribution to a further landmark work of what would become International Modernism: the cantilever tubular steel chair. A work, allegedly, initially inspired by a foldaway car seat Stam saw in Frankfurt in 1926, and whose realisation was informed by his dislike of “the closed cube of the four-legged chairs that the Berlin allotment gardeners used to build of old gas pipes”.6 Thus a mid-1920s Readymade not arising from the Surrealists of Paris, but the inarguable logic of an anonymous Berliner; and a Readymade which Stam adapted, keeping the gas pipes and joints, but removing the back legs, thereby disrupting the cube, the space, the convention, opening the closed construction and in doing so invigorating developments in a genre of seating that, one gets the impression, was very much in the air in the mid-1920s, but which was still searching for its natural expression.

Stam’s, more refined, domesticated, expression of the tubular steel cantilever chair being first articulated in his W1, a work premiered in context of the 1927 Weissenhofsiedlung building exhibition in Stuttgart, an exhibition to which Stam contributed a row of three quadratic, flat-roofed, two storey houses whose open plan living room could be sub-divided via a, sliding, partition wall, and importantly Stam’s first realised constructions. And a work which was central to the legal dispute over the authorship of the steel tube cantilever chair, one of the most interesting legal disputes ever in the (hi)story of furniture design, and a dispute whose resolution on June 1st 1932 saw Mart Stam awarded the artistic copyright of the quadratic cantilever chair.

On June 1st 1932 the Supreme Court of the German Reich Leipzig awarded Mart Stam the artistic copyright of the quadratic cantilever chair…..

Parallel to developing his W1 and his Weissenhofsiedlung project Mart Stam remained with Brinkman and Van der Vlugt, until April 1928 when Leendert van der Vlugt fired Stam, allegedly because he had claimed authorship of the Van Nelle Factory. An authorship he may or may not have had. As already noted, Stam’s exact role in the Van Nelle Factory remains somewhat opaque.

And a dismissal that in many regards proved fortuitous as it allowed Stam in August 1928 to join Ernst May and his Neues Frankfurt project where, in addition to a retirement home realised in cooperation with Ferdinand Kramer, Werner Max Moser and Erika Habermann, his primary contribution was without question the Hellerhof Siedlung; an estate of some 1200 flats in Frankfurt-Gallus and a project which represented Stam’s first opportunity to develop on a large scale his ideas on not just construction and architecture but of affordable, social, urban housing he had been developing since, arguably, his work on Vreewijk a decade earlier. Albeit in a very much evolved material and formal expression from the brick and gable roofs of Vreewijk. If the communal green spaces remained.

And ideas he would soon get the chance to develop on an even larger scale: in 1930 Mart Stam travelled with Ernst May, and some 30 other Neue Frankfurtiers to the Soviet Union to participate in the construction effort associated with Stalin’s first five year plan, and where he was involved with the construction of the new town of Magnitogorsk on the edge of the Ural mountains, and the development and expansion of Orsk and Makejevka, the later in the contemporary Ukraine; before, unofficially officially on account of his refusal to construct a new city on a site he considered polluted and uninhabitable on the banks of Lake Balkhash in the contemporary Kazakhstan, he returned to Holland in 1934.

Although by that stage relations between the Soviet authorities and the May Brigade were in any case not the best.

Settling in Amsterdam Mart Stam, and his then wife, the ex-Bauhäusler, Lotte Stam-Beese established a joint architectural practice and began cooperating with Willem van Tijen and Hugh Maaskant, and thus those architects who post-War a freshly graduated Fritz Haller would spend a year working for in Rotterdam. Among the most notable, and tangible, results of Stam-Beese, Stam, van Tijen and Maaskant’s cooperation is without question the so-called drive-in houses in Amsterdam’s Anthonie van Dijckstraat, so-called because they feature on the ground floor a private garage, a novelty in mid-1930’s Amsterdam, and a feature which allowed one to drive-in to your apartment.

Mart Stam’s post-USSR return to Holland also saw him begin his formal career as an educator with his appointment in 1939 as Director of the Instituut voor Kunstnijverheidsonderwijs, IvKNO, the contemporary Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam, an institute which according to the magazine De 8 et Ophouw was “an institution that in recent years visual artists have lost interest in, and which is somewhat dazed and fallen asleep”7 and which Stam sought to reawaken along Bauhaus lines, including the introduction of a preliminary Vorkurs.8

And then, as so often in the early 1940s, came the War, and although the school continued to nominally operate, it did so under the auspices of the occupying Nazi’s, and so effectively didn’t operate. And certainly not as a school modelled on Bauhaus. Mart Stam keeping himself busy during the War in the Amsterdam Resistance, including working with the Persoonsbewijzencentrale, an organisation which in the course of the War years supplied tens of thousands of “undesirables” with forged identity cards and documentation.9

Post-War Stam continued his process of reforming the IvKNO, for all of moving the focus of the school away from the artist and the unique to the industrial and the serial, a process in which he met with considerable resistance from a goodly number of the staff and students, for all those predisposed to and admiring of the artist and the unique, but also from those who saw a communist manifesto behind his artistic and pedagogic reforms, and a process which, logically, led to much tension within the institute.

Much more cordial were Stam’s post-War relationships with the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam’s Director Willem Sandberg. The pair had first met in 1934, had cooperated in the Wartime Resistance and post-War Stam contributed to the organisation and design of exhibitions at the Stedelijk, most notably the 1946 Piet Mondriaan commemorative exhibition, while, and amongst other cooperations, the pair co-founded the avant-garde magazine open oog, open eye, and also co-established the Goed Wonen Stichting, an initiative which aimed to “raise domestic life in the Netherlands to a higher level by improving home furnishings in the broadest sense of the word, by promoting the production and distribution of furniture, furnishings, utensils, etc., which meet certain aesthetic, technical and social demands”,10 and which can very much be considered part of the “good taste”, “good design”, initiatives the proliferated in the immediate post-War years. And continue unabated to this day.

And “certain aesthetic, technical and social demands” that Stam, one presumes, saw embodied in a collection of Standaardmeubels, Standard furniture, he developed for Goed Wonen from 1945 onwards, a collection of wooden furniture, including a not uninteresting looking bookcase/storage unit. That the use of wood was more about available resources, and arguably public acceptance, rather than any change in understanding on Stam’s part being made clear by a most interesting, and criminally unrealised, steel tube sofa design from ca 194511 and which not only features head height side panels reflective of many a settle, or wingbacked armchair, but in whose proposed toned colour scheme predicts Hella Jongerius’s Polder Sofa. If Stam’s inspiration was also the polders of Holland is not recorded. But something tells us it wasn’t.

However despite such a wide range of activities resistance to Stam, both Stam the person and Stam the Marxist was, by all accounts, not just limited to the IvKNO, but expressed in wider circles, which, arguably, helps explain that despite the necessary post-War reconstruction needs Stam was receiving next to no architectural commissions, certainly none in the large scale public housing that had been such a focus pre-War; or put another way, mid-1940s Amsterdam wasn’t a time and place that offered Mart Stam much opportunity and freedom for the large scale development and expression of his ideas. Or indeed hope that he would ever acquire such. “And then” as his third wife Olga recalled, “we .. received the invitation to Dresden. Mart Stam shone with joy, enormous impatience took hold on him – a quick departure was required and so it happened!”12

And thus in June 1948 Mart and Olga Stam swapped Holland for the Sowjetische Besatzungszone, and the future DDR……

Drive-in houses, Anthonie van Dijckstraat Amsterdam by Stam-Beese, Stam, van Tijen and Maaskant (photo courtesy Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed via commons.wikimedia.org)

……and an aspect of Mart Stam’s biography we’ll discuss in more detail in a coming post.

Here it suffices to note that upon his arrival in the Sowjetische Besatzungszone Stam was initially charged with overseeing the fusion of Dresden’s two creative colleges, the Kunstakademie and Hochschule für Werkkunst, a fusion that awakens memories of the fusion of Weimar’s two creative colleges three decades earlier; and a fusion which met with just as much resistance as that in Weimar.13 Not least on account of Stam’s plan to, as it were, make the fine arts subservient to the applied arts, or as he phrased it, “and if we take special care of drawing, this is not because we primarily want to strive for the excellent individual drawing, but in order to reach a higher level of illustration, especially book illustration”14 And thus a Functionalist understanding of the role of creatives, for the service of industry, and one which the staff and students at the Kunstakadamie were fundamentally opposed to. And which awakens memories of tensions associated with Stam’s tenure at the IvKNO, tensions, at least partially, caused by Stam’s desire to move the focus of the school away from the artist and the unique to the industrial and the serial.

And tensions which ultimately saw Stam move(d) from Dresden to East Berlin and the Kunsthochschule Berlin, the contemporary Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weissensee, and where he found not only an environment more supportive for his ideas, but through the establishment of the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung a vehicle via which to pursue his vision of a close cooperation between creative colleges and industry, of a school, its staff and students as partners of industry who “through exemplary form-giving [seek to] achieve a refinement of the products of mass use, and thus to raise the general cultural level”.15 And thus by extrapolation a partner of society through ensuring that industry produced that which was functionally and formally relevant for the age and the contemporary society. An idea that goes back to the early Art Nouveauists of the late 19th/early 20th century; and also neatly mirrors that which in the early 1950s developed, albeit with slightly less Socialist avidity, in West Germany at the HfG Ulm.

That such cooperations developed so much more successfully in Ulm than East Berlin can be understood in the so-called Formalism Debate that developed in East Germany in the early 1950s. A debate we’ve oft discussed in these dispatches, will discuss again before too long, and which, in essence, saw the DDR leadership denounce International Modernism, Functionalism, Bauhaus et al as enemies of the people and demand more “traditional”, monumental, representative art, architecture and design. A debate which obviously wasn’t going to leave a Mart Stam unaffected, and certainly not after the SED politician Ernst Hoffmann pronounced in 1951, “…Genosse Stam, is a formalist…”.16 Which he may or may not have been. But did mean a longer stay in the DDR was impossible and thus, and against a background of increasing hostility, on January 1st 1953 Mart and Olga Stam quietly left the DDR returning, once again, from an ill-fated sojourn in a Socialist Republic, to Amsterdam…..

3101 chair from VEB Stima Stendal (l) Werkstattstuhl by Mart Stam for Kunsthochschule Berlin Weissensee (m) & Seminarstuhl Selman Selmanagic, Herbert Hirche & Liv Falkenberg for Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau (r), as seen at Shaping everyday life! Bauhaus modernism in the GDR, Dokumentationszentrum Alltagskultur der DDR, Eisenhüttenstadt

……and where, in many regards, Mart Stam picked up where he’d left off in 1948.

Initially taking up a post with Merkelbach and Elling, with whom he’d cooperated on several projects in the 1940s, in 1956 Mart Stam established his own practice in which context he contributed to the construction of the new Geuzenveld housing estate in Amsterdam; contributed to (further) developments of the new town of Nagele in Noordoostpolder, a project which had begun in the 1940s as an initiative of the functionalist orientated architecture group De 8; and the construction of the headquarters of the publishing company Geïllustreerde Pers in Amsterdam, Mart Stam’s last large scale public building, and a work whose glass curtain wall and concrete core reflect elements of Stam’s understandings of construction and form, and whose variable interiors with moveable walls both reflect Stam’s understandings of functionality and also echo the sliding, partition walls of his Weissenhofsiedlung houses from 1927.

In addition Stam picked up his cooperations with Willem Sandberg, both in context of the Stedelijk Museum but also developing projects for the Willet-Holthuysen Museum and the Fodor Museum and also picked up again his association with Goed Wonen.

And also, one gets the feeling reading between the lines, that he picked up once again the sense of the hopelessness that had existed in the late 1940s, a realisation that Holland (still) had little need for him, a situation, as Stef Jacobs opines, arising because not only had Dutch society moved on, but Holland had become much more prosperous and understandings of architecture, design, art and the relationships between such and the individual had moved on, become more removed from those of Stam.17 And a situation compounded by the disappointment of his experiences in the DDR. In addition, and again reading between the lines, one gets the impression that as the 1950s progressed Stam began to understand that mass public housing which he’d long understood as an answer to social demands and realities, a service to society, a key component of creating de nieuwe wereld, had become a commodity, the domain of the capitalist. With the associated shift in focus when developing projects.

Then there was the fact he was still considered with suspicion on account of his left wing politics. Or as Fré Smidt, one of Stam’s employees of the period noted, “Je gaf geen werk aan een communist.” You didn’t give work to a communist.18

And thus it came that in the autumn of 1966 Mart and Olga Stam once again left the Netherlands. Initially to Israel where they spent three months travelling before settling in Switzerland. Whereby “settling” is perhaps an optimistic phrase, the pair regularly moving, initially living in houses built by Stam, Mart Stam’s very last constructions: specifically the Villa Mostam in Arcegno on the banks of Lago Maggiore, “Mostam” being one of several aliases the pair used in Switzerland – Mostam = Mart Olga Stam – and Villa Heller in Hilterfingen, near Thun, before switching to an existence based in ever changing hotels and spas. And slowly, and deliberately, vanishing from public life, something neatly underscored by Stam’s answer to, then, TECTA managing director Axel Bruchhäuser who in 1977 had tracked him down: “Ich kenne keinen Mart Stam.” I don’t know a Mart Stam.19

Bruchhäuser could however tease the memory out of him and convince him to contribute to the new chair museum he, and TECTA, were developing at Burg Beverungen. And also reawaken an interest in furniture design: Stam and Bruchhäuser agreeing a never realised cooperation, while in 1979 Thonet released with Stam’s S 67 a reworking of Marcel Breuer’s S 64, and also developing a prototype for a cantilever wingbacked armchair.20

However his re-appearance was brief and, arguably, driven by his deteriorating mental health21 Mart Stam quickly re-removed himself from public life, before on February 23rd 1986 Mart Stam died in Goldach on the Swiss banks of the Bodensee aged 86.

By necessity of the confines of space and time the above is but a heavily abridged tour through the life and career of Mart Stam, the inter-twinned realities of his varied spheres of work, be that architecture, design, education, publishing, journalism, exhibition design, urban planning, et al; his varied physical places of work, few architects of his age were so mobile and transient; and the varied connections he maintained, for all in context of organisations such as, and amongst others, De 8, Opbouw or the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne mean that any journey towards Mart Stam is one that can, and must, be made by various routes.

And routes we’d recommend you take for in doing so one approaches not only a better understanding of the hows, why and wherefores of Mart Stam, not only better, more differentiated, understandings of the development of architecture and design in the middle decades of the 20th century, but also allows for a better understanding of the de nieuwe wereld Mart Stam envisaged.

A world that was informed on the one hand by Stam’s political views, views formed in the fervour of the Great War as experienced in neutral Holland by the teenage Stam,22 and on the other hand by the discussions on the role and function of architecture, the connections between architecture, society, the individual, against which the young Stam began his career; one must always remember that Stam is around a decade younger than the likes of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Ernst May, El Lissitzky, J.J.P. Oud and many of the others who in the course of the 1920s developed not only arguments for the future of architecture/society, but tangible expressions of those arguments, and in doing so influenced and informed the understandings and positions of a Mart Stam.

Understandings and positions he subsequently expressed in his buildings, in his urban planning, in his structuring of education, in his furniture designs; and understandings which, and simplifying to the point of inaccuracy, can be summarised as concerning themselves with subjects such as, and amongst others, the nature of construction, that “the problem of modern architecture is not a form problem”23, but one of construction, “the processing of building materials, which used to be done by the craftsmen, is now done faster and cheaper by the machine. However, construction itself has remained manual. This manual building process must make space for a new construction”24, consequently “we need to identify the constructive necessity in each task and solve this in the simplest and most economical way”25, and that, “modern construction leads to new systems, it follows the constraint of the economy. The architect undertakes the task – free of aesthetic tradition – carefree about the pursuit of formal beauty – and thereby achieves an elementary, correct, solution.”26

With a flexibility, motion, in architecture, a further problem of contemporary architecture being that “we build monuments, which in principle are meant to remain for eternity”27 whereas,”the building must be utilisable in the widest sense”,28 something achieved through, and amongst other considerations, the selection of an appropriate construction system, one which “offers many possibilities and is as viable as possible”29 so that “a building, built today as a bank, should be able to be used tomorrow as an office building, department store or hotel”30

With what Werner Möller describes as Stam’s striving for “a new collective social code”,31 a society in which new understandings would see “the individualistic ceded to the general”.32 Meaning for design “the modern artist will regain full interest in the problems of the general public through this new attitude to life”, thereby “a design will emerge that avoids any formalistic tendency, that is not born out of the artist’s particular instinct or out of a fantastic inspiration of the moment, but is based on the general, the absolute”.33 While in terms of architecture and urban planning, “[over time] our demands increase, making it is necessary to accept those means that enable us to meet our demands with a minimum of effort”, or put another way, “we will have to replace the domestic laundry with the central laundry, the individual storage cellars with the depots of the consumer associations, individual heating with district heating, and maybe replace the individual apartment kitchen with the central restaurant, the communal dining room”34

With the goods with which we surround ourselves, “it is necessary to understand how much in our apartments is superfluous. A situation for which much blame lies with industry. Driven by competition, it lets one novelty follow another without always proving a need for these “inventions”,35 a situation which sees the appropriate, best suited solution replaced by pure representation which “is not a human measure, it is excessive, it is want to impress, it is wanting more than the truth”36 that “we have to fight ceaselessly against the stupid privately-built house and the miserable characterless furniture: and strive for the attainment and realisation of higher and more humane values – for a better environment”37 and that “our culture, the culture of our century, however, should be measured according to the cultural level of the apartment, the furniture, the crockery and all objects in the daily life of the working person”38

And that because “life tolerates no representation, no monument, no symbol” rather “it only tolerates solutions to meaningful tasks that can serve the ends of people.”39

And regardless of the validity, or otherwise, of Mart Stam’s positions40 on the future of architecture, design and society, or perhaps better put, regardless of your personal assessment of the validity, or otherwise, of Mart Stam’s positions on the future of architecture, design and society, reflecting on them, allows one not only to understand how closely related architecture, design and society are or that while Mart Stam may not have changed the world, he actively contributed to the discussions of his time and that over the intervening decades others have taken up his thoughts and evolved them for their own time, but for all allows space for each and everyone of us to reflect on the future of architecture, design and society.

Which is important, for if one thing is clear, it is that wij hebben de nieuwe wereld te scheppen…….

Happy Birthday Mart Stam!

1. Mart Stam, ’t Gebed en de sociale gedachte’,1919, reprinted in Stef Jacobs, Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas. Doctoral thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016. Available via https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.540323 (accessed 05.08.2020)

2. Door H Buys, Mart Stam, Elsevier’s Geïllustreerd Maandschrift, Volume 49, Nr 98, July-December 1939

3. Not uninteresting is the fact that in 1919 Stam’s future colleague Margarete Lihotzky was also in Rotterdam, using her time to study, amongst other things Dutch garden villages. And, one presumes, Vreewijk. If they met is not recorded, but one assumes their paths must have crossed.

4. Herman van Bergeijk, “Ein großer Vorsprung gegenüber Deutschland”. Die niederländischen Architekten auf der Bauhausausstellung von 1923 in Weimar, RIHA Journal 0064, 17 January 2013

5. See Letter from Stam to Werner Max Moser 25th September 1925, reprinted in Werner Oechslin, Mart Stam: eine Reise in die Schweiz; 1923 – 1925, gta-Verlag, Zürich, 1991. In 1929 Sigfried Giedion postulated that Stam may not have been officially registered in Switzerland and may have been obliged to leave when found out, see Werner Möller, Einleitung, Mart Stam: 1899 – 1986; Architekt – Visionär – Gestalter; sein Weg zum Erfolg 1919 – 1930, Wasmuth,Tübingen, 1997 footnote 118

6. Quoted in Der Kragstuhl / The Cantilever Chair, Stuhlmuseum Burg Beverungen, Alexander Verlag Berlin, 1986. Also quotes Ferdinand Kramer as stating the original inspiration was a foldaway car seat

7. Joke Hofkamp and Evert van Uitert, De Nieuwe Kunstschool (1933—1943), Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art, Vol. 30, Kunstonderwijs in Nederland (1979), pp. 233-300 In addition one must point out that Stam was a member of the associations De 8 and Opbouw and closely related with publication De 8 en Opbouw

8. And thus a not uninteresting association with Bauhaus, because as Werner Möller notes in 1926 Walter Gropius actively sought to recruit Stam to head the new architecture department at Bauhaus Dessau, a post Hannes Meyer ultimately took over, Stam’s rejection apparently being because he had little interest in becoming an educator. A decade later he cleary saw things differently, seeing education as an important factor in evolving understandings. See Werner Möller, Einleitung, Mart Stam: 1899 – 1986; Architekt – Visionär – Gestalter; sein Weg zum Erfolg 1919 – 1930, Wasmuth,Tübingen, 1997

9. Stef Jacobs, Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas. Doctoral thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016 page 249ff

10. J. Bommer, “Wat wij willen”, in Goed Wonen 1, 1948 quoted in Stef Jacobs, Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas. Doctoral thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016 page 284

11. See, Stef Jacobs, Oeuvrecatalogus, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016 Available via https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.540323 (accessed 05.08.2020) Standaardmeubels page 154ff. Sofa on page 157, in black and white and in colour on page 399 of Stef Jacobs, Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas

12. Olga Stam-Heller, Chronologie 30, quoted in Stef Jacobs, Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas. Doctoral thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016 page 288

13. See Wolfgang Rother, Mart Stam in Dresden, in Rainer Beck & Natalia Kardinar [Eds] Trotzdem. Neuanfang 1947, Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, 1997

14. Staatsarchiv Dresden, Besatand Landesregierung Sachsen, Akte Ministerium für Vlksbildung Nr. 1658, quoted in Gerhard Hirche Die Jahre des Neubeginns nach der Zerschlagung des Facshismus, in Dresden. Von der Königlischen Kunstakademie zur Hochschule für Bildende Kunst 1764-1989, Verlag der Kunst dresden 1990 Page 419

15. Mart Stam, Entwurf “Institut für industrielle Gestaltung”, August 1950, reprinted in Hildtrud Ebert [Ed] Drei Kapiel Weißensee, Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weißensee, 1996

16. Hans Lauter, “Der Kampf gegen den Formalismus in Kunst und Literatur, für eine fortschrittliche deutsche Kultur. 5 Tagung des Zentralkomitees der SED vom 15-17 März 1951”, Dietz Verlag, Berlin, 1951

17. See Stef Jacobs, Mart Stam. Dichter van staal en glas. Doctoral thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016 page 304ff

19. Quoted in context of the exhibition Radikaler Modernist Das Mysterium Mart Stam at the Marta Herford, see https://www.fh-muenster.de/fb5/aktuelles/pressemitteilungen/mart-stam.php (accessed 05.08.2020)

20. See, Stef Jacobs, Oeuvrecatalogus, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2016. The S 67 F is on page 213, but also appears to be the similar to a proposals for TECTA (page210/211) and also a 1938/39 chair for Thonet (page 143) Essentially Stam takes Breuer’s single piece chair and separates it into frame and armrest segments, and that, arguably, not particularly elegantly, the vertical tubes behind the backrest tending to stand there a bit lost. While there is an extra production step necessary to join the armrests to the frame. However as a construction principle allows the creation of the wing backed armchair S 68 (page 214)

21. The word “paranoia” is often used in context of Mart Stam’s later years, if it technically was or if he suffered from some similar, possibly age related, mental illness can no longer be confidently diagnosed. However clearly something triggered such an extreme reclusive behaviour and a compulsive nomadic lifestyle.

22. It is not possible to consider Mart Stam without considering his politics, and to question not only his motivations for travelling to the Soviet Union and the DDR but also to ask if those decisions should be reflected in our assessment of his position in the (hi)story of architecture and design, can one separate a creative from the regimes they work with and for? And we will do in a coming post…..

23. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, i10 International Revue, 1/2 1927

24. Mart Stam Modernes Bauen 1 ABC Beiträge zum Bauen 2 1924

25. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, Bauhaus Volume 2 Nr 2/3, 1928 reprinted in Mart Stam: documentation of his work 1920-1965, RIBA Publications, London, 1970

26. Mart Stam Modernes Bauen 1 ABC Beiträge zum Bauen 2 1924

27. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, i10 International Revue, 1/2 1927

28. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, i10 International Revue, 1/2 1927

29. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, Bauhaus Volume 2 Nr 2/3, 1928 reprinted in Mart Stam: documentation of his work 1920-1965, RIBA Publications, London, 1970

30. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, i10 International Revue, 1/2 1927

31. Werner Möller, Einleitung, Mart Stam: 1899 – 1986; Architekt – Visionär – Gestalter; sein Weg zum Erfolg 1919 – 1930, Wasmuth,Tübingen, 1997

32. Mart Stam, Kollektive Gestaltung, ABC – Beiträge zum Bauen, 1, 1924

34. Mart Stam, Das Mass. Das richtige Mass. Das minimum-mass. Unsere Hausgeräte und Möbel, Das neue Frankfurt: internationale Monatsschrift für die Probleme kultureller Neugestaltung, Nr 3, 1929

35. Mart Stam, Fort mit den Möbelkünstlern!, Werner Graeff, Innenräume, Akad. Verlag Dr. Fr. Wedekind & Co, 1928 reprinted in ABC – Beiträge zum Bauen 4 1927/28

36. Mart Stam, Das Mass. Das richtige Mass. Das minimum-mass. Unsere Hausgeräte und Möbel, Das neue Frankfurt: internationale Monatsschrift für die Probleme kultureller Neugestaltung, Nr 3, 1929

37. Mart Stam, Armoede of welstand?, open oog. avantgardecahier voor visuele vormgeving, 1, 1946 translated and reprinted in Mart Stam: documentation of his work 1920-1965, RIBA Publications, London, 1970

38. Mart Stam, Wünscht das Publikum Schund und Kitsch? Neues Deutschland, 20th September 1949

39. Mart Stam, M-Kunst, Bauhaus Volume 2 Nr 2/3, 1928 reprinted in Mart Stam: documentation of his work 1920-1965, RIBA Publications, London, 1970

40. Mart Stam clearly wasn’t alone in such positions, nor did he develop all by of them himself, rather he was, as we all are, a moment in an ongoing helix……In addition, a more detailed analysis of his various texts invariably leads to a number of contradictions, inconsistencies, improbabilities, but that’s why you should read them rather rely on brief quotations….

Tagged with: Cantilever chair, Mart Stam