Radio smow: A Bauhaus Playlist…….

Bauhaus Weimar’s centenary may now be behind us, but there remains a lot of discussion, consideration and reflection ahead of us. Not least in context of the rapidly approaching Bauhaus Dessau centenary.

By way of an accompaniment to those reflections, considerations and discussions, and of engendering a differing perspective on both the schools and the contexts in which they existed, a Radio smow playlist devoted to music of, from and associated with the Bauhauses.

“In Weimar I heard Klee playing his violin, unfortunately only the once!” lamented Marianne Brandt in 1966, however she could console herself with the memories of, “Kurt Schwitters, in Weimar and in Dessau: “Was trägst du dein Härchen wie einen hut?” the “Sinfonie in Urlauten” or “Sie war schon immer ein gescheiteltes Mädchen gewesen” etc. Who still remembers such! Palucca thrilled us when she brought her latest dances, and Béla Bartók!”1

As an art, craft, design and architecture school, music was never formally a component of the Bauhaus programme; however, and as Marianne Brandt very neatly illustrates, within that programme, and around the edges of the institutions, amongst its staff and students, music played, pun intended, a not irrelevant, certainly not uninteresting, not unimportant and for all figurative role in the lives, existences, and developments of the schools.

A relevance, importance and association which means a complete analysis of the nature of the relationships between Bauhaus and music is far, far outwith the spatial confines of this blog, even given our proclivity for, and delight in, exploding spatial borders; however, by way of the briefest of brief illustrations, a selection of music that highlights aspects of those relationships. And, hopefully, provides a little motivation for more research on your own…….

Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major, BWV 552 by Johann Sebastian Bach

Against the background of the 1919/1920 Bauhausstreit, Bauhaus Dispute, and the increasingly fierce attacks on the institution from within sections of Weimar society, Walter Gropius organised a so-called Morgenfeier, Morning Service, to be staged in Weimar’s Deutsches Nationaltheater on March 21st 1920. Essentially a (PR) platform for Gropius to present the school and his ideas to both the Weimar public and also, as Volker Wahl underscores,2 the Members of the Thüringen Regional Parliament, who at that point were negotiating the State budget, including Bauhaus’s share of that meagre pie, and who were not only well aware of, but at times initiators of, the criticisms of the school, the Morgenfeier was planned to feature two lectures: one by Gropius on the Bauhaus Concept and one by Johannes Itten on The teachings of the old masters, the two lectures sandwiched between the Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major by Johann Sebastian Bach. Whereby, and as with the choice of lectures, the choice of Bach was carefully considered.

Born in nearby Eisenach and a former resident of, and Concert Master in, Weimar, Bach was not only an artist closely associated with Weimar and Thüringen, but in the early decades of the 20th century was an artist enjoying an exponential rise in posthumous popularity, or as Wolfgang Rathert phrases it, “the mythologisation of Bach in German music culture, which increased to a level of collective hypnosis, the extent of which can only be compared to the Wagner-cult, is reflected on many levels of literary, compositional and interpretative appropriation.”3 Bach, and the wider Baroque, were very much in in 1920s Germany, and that both amongst conservative cultural factions as more liberal cultural factions. Thus, as Martha Ganter argues, Bach can be understood as a “connecting element of a collective cultural identity”4 between those conservative residents of Weimar Klassik and those liberal residents of Weimar Moderne. Bach’s fugue, if you so will, serving as a Fuge…….a little joke there for all you Germanophone musicologists.

The reasons the numerous Bauhäusler were attracted to Bach are, arguably, as numerous as the Bauhäusler; however, amongst the more notable Bachees: Lyonel Feininger once opined that, “…what I consider of utmost importance is to simplify means of expression. Again and again I realize this when I come to Bach. His art is incomparably terse, and that is one of the reasons that it is so mighty and eternally alive”5; Paul Klee, may, as Susanne Fontaine notes, have had Mozart at the top of his “musical hierarchy”6 but an idea of how Bach flowed into his art can perhaps be gleaned by his use of the first two bars of the Adagio from Bach’s Sonata for Violin and Cembalo obligato in G major, BWV 1019, as the basis for a class at Bauhaus Weimar on how paintings can be developed from music7, and that not as an abstract practical exercise, but as a demonstration of his understanding of the near innate connection between art and music, an understanding that infuses through his work; similarly for Johannes Itten Bach was a source of inspiration in terms of not just construction, proportion, colour et al, but one’s relationship to a work, once noting that “I do not understand agitation and emotion as a sentimental feeling, but rather as that inner, vibrating, exaltation into which we are carried when we experience Bach’s fugue…”8, while beseeching on another occasion “Oh, just once in my lifetime I wish to create a work that can stand alongside Bach.”9

Add to the numerous Bauhaus Bach devotees the likes of Oskar Kokoschka, Theo van Doesburg or Adolf Hölzel, to name but three, and one approaches an understanding of Friedrich Teja Bach’s opinion that, “No other composer from the history of music has endowed the art of our century with as many stimulations as Johann Sebastian Bach.”10 Nor could any other have so united the conflicting factions in Weimar in 1920.

That as a consequence of the so-called Kapp-Putsch on March 13th, and subsequent civil unrest, the Morgenfeier wasn’t staged, is, we’d argue, largely irrelevant. Alone its planned existence, the motivation that lay behind it, the thought that went into its planning, and the inclusion of Bach, very neatly encapsulating the atmosphere in Weimar in early 1920.

Pierrot Lunaire by Arnold Schönberg

According to Martha Ganter11, a from Bauhaus co-organised performance of Arnold Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire in Weimar on October 27th 1922 represents a defining break in the music Bauhaus used for representative purposes, and that from that moment on only contemporary, modern, music was employed; a switch, if one so will, away from the “connecting element” of the Baroque of a Johann Sebastian Bach to the, arguably, divisive element of the new music of an Arnold Schönberg; and, one could argue, a switch enabled by a fading, or perhaps better put, normalising, of the Bauhausstreit, and a feeling at the school that it could, must, represent itself more self-confidently and openly, without all to great reflection on the conservative forces in the town.

New as the position may have been. Arnold Schönberg was no new name at Bauhaus Weimar.

Quite aside from the person of Erwin Ratz, Secretary to Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, and a former pupil of Schönberg’s in Vienna, the most direct link to Schönberg was that of Wassily Kandinsky. Following his attendance at a Schönberg concert in Munich in January 1911 Kandinsky made contact with the composer and the two established a long friendship and professional exchange, one in many ways defined by a common understanding of the connections between their genres and their attempts to forge new ways with and for their art, or as Kandinsky wrote to Schönberg in that first letter from January 1911, “I believe that today’s harmony is not to be found in the “geometric” way, but in the direct anti-geometric, anti-logical. And this path is the “dissonance in the arts”, in painting as well as in music … And the dissonance in “today’s” painting and music is nothing but the consonance of “tomorrow”… I was immensely happy to find the same idea in your work.”12

Beyond such a communally approached questioning of geometry, harmony and form, as Dieter Bogner notes, “Kandinsky and Schönberg were both concerned with the contemporary question amongst the artistic avant-garde of the synaesthetic relationships between sound and colour.”13

A question that at Bauhaus Weimar was largely the responsibility of Gertrud Grunow, “die Seelenhüterin des Bauhauses“, “the spiritual guardian of Bauhaus”, as Felix Klee once referred to her,14 and who from 1919 until March 1924, taught Harmonisierungslehre, Harmonisation Theory, initially on a freelance basis but from June 1923 as Außerordentliche Formmeister, making her, in effect, the first female Bauhaus Meister. And a largely forgotten Bauhaus Meister.

A central component of the Weimar Vorkurs, Grunow’s Harmonisierungslehre was, in many regards, a form of a concentration theory, a methodology for helping one balance the physical and psychic self, and thereby helping bring the creative to a place of creativity. Or as Grunow noted in her essay for the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition catalogue, “the artist creates unconsciously and so has to go beyond the conscious”15, words which neatly reflect those of Arnold Schönberg to Wassily Kandinsky that “any act of formation that strives for traditional appeal is not entirely free of acts of consciousness. And art belongs to the unconscious! One should express oneself! Express oneself directly!”16 Positions which raise very obvious parallels to André Breton’s 1924 Surrealist Manifesto and the power of the unconscious, and which thus not only tends to further underscore the understanding from the exhibition Objects of Desire. Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today at the Vitra Design Museum that the varied developments in creative expression of the 1920s and 30s are differing paths of common origin, but also further underscores the importance of Sigmund Freud and the exploration of the mind in the development of creativity of all genres in the early 20th century.

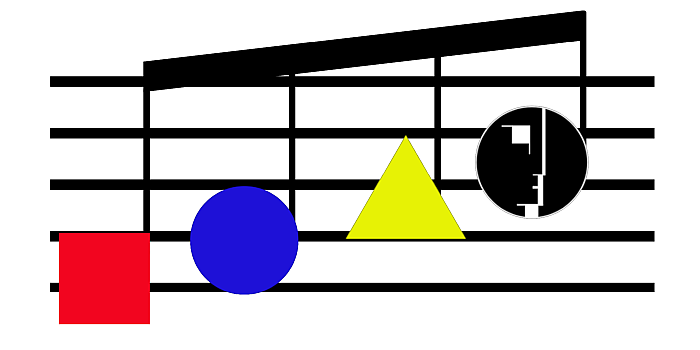

Gertrud Grunow’s teaching was based around a circle of twelve colours corresponding to the twelve-tone, chromatic, scale, each colour representing a note, for example, white = c, green = f, yellow = h.17 And thus not only a further applied understanding of colour to compliment Kandinsky’s “yellow triangle, blue circle, red square” colour theory in the Weimar Vorkurs, but an understanding based on the tonal scale of the twelve-tone music of a Schönberg. Or a Josef Matthias Hauer; who became acquainted with Johannes Itten in 1919 and with whom he forged a, ultimately unsuccessful, plan to establish a music department at Bauhaus, or more accurately put, a music school in Weimar closely associated with Bauhaus, and thus a contra-point to the existing Staatliche Musikschule, an institution which had its origins in the 1872 Weimarer Orchester-Schule, the first orchestra school in the (future) Germany, and an institution still very much positioned as such. A thus a move which would, could, only have exasperated the already fractious Bauhausstreit.

The close friendship between Itten and Hauer, between Kandinsky and Schönberg and the experience of the Harmonisierungslehre classes, or at least amongst those who responded positively to the methodology, meant that twelve-tone music was a popular, and influential, genre at Bauhaus Weimar; or as the critic and musicologist Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt noted of his time in Weimar ahead of the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition, “that there were spiritual similarities between the constructivists of the Weimar Bauhaus and the twelve-tone techniques of the Viennese liquidators of tonality was clear to any one who had an insight into the workshops of both groups”18 And in 1923 he did.

In addition, and while in many regards an aside, it is also interesting to note that in April 1919, and thus in the first month of Bauhaus Weimar’s formal existence, Gropius wrote to Ernst Hardt, Intendant of the Weimarer Hoftheater and, as noted from our post from the Stadtmuseum Weimar’s Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven exhibition, along with Wilhelm Köhler, Director of the Weimar Art Collection, an important protagonist on the side of the Weimar Moderne, with the request that he consider which musicians should, must, be invited to Weimar as part of a planned summer festival. Stressing the importance in choosing the correct musicians, Gropius noted, “when a Schönberg or a Pfitzner comes to Weimar, the whole world will be aware of the fact”.19 Arguably marginally hyperbolic, yet a sentence which nonetheless succinctly underscores how very aware Gropius was of Bauhaus’s place amongst the cultural avant-garde of the period, but for all, how aware he was of the importance and relevance of the public interpretation of and response to that which Bauhaus presented. And thus why the 1920 Morgenfeier was to feature Bach and not Schönberg. Pierrot Lunaire would not have been a “connecting element” in March 1920. But by October 1922, no-one was searching for such.

Perpetuum mobile, BV293 by Ferruccio Busoni

Amongst the more important, and interesting, moments in the Bauhaus (hi)story is, without question, the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition, an event, which beyond presenting works by Bauhäusler, including with Georg Muche’s Haus am Horn the first collective project of the Weimar workshops, and the only architecture project realised in Weimar, also featured an accompanying cultural programme, the so-called Bauhauswoche, Bauhaus Week. In addition to lectures, including Gropius’s on “Kunst und Technik, eine neue Einheit“, “Art and technology, a new unity”, which signalled the shift in Bauhaus from craft to industry, the Bauhauswoche programme also included theatre, specifically performances of the Triadisches Ballett and Mechanische Kabarett, and a series of concerts in Weimar’s Deutsches Nationaltheater featuring works by Ernst Krenek, Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith who premiered his freshly composed Marienlieder which he subsequently reworked as his Opus 27 Marienlebe, and Ferruccio Busoni, including his 1922 Perpetuum mobile, BV293 part of his Klavierübung, Piano Tutorial, project and the premiere of the first 3 of the 5 kurze Stücke zur Pflege des polyphonen Spiels. And thus a programme which neatly underscores the importance of contemporary music at Bauhaus in that period.

The Bauhauswoche was brought to a close on Sunday August 19th with a lampion parade and party in the Armbrust clubhouse featuring two so-called Reflektorische Spiel, light/colour/music installation/projections by Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, and a performance by the Bauhauskapelle, that ubiquitous musical soundtrack to Bauhaus festivities; the party went on till sunrise and, as Stuckenschmidt recalls, “We were all wearing the most fanciful costumes and mostly masked … The Kapelle alternated between jazz, blues and folk dances. The whole event had the feeling of youthful constructivist upheaval”. Whereby he also notes that, “Wilhelm Wagenfeld watched the colourful hustle and bustle quietly and thoughtfully.”20 Which, and without having ever met Wagenfeld, we can well imagine he did.

According to Gropius over 15,000 visitors attended the Bauhaus Exhibition over its six week run21, which may not sound many, but one must remember it was very, very troubled days in Germany and for all the year of hyper-inflation, and so the fact that anyone visited was in many ways a major success. And while from existing records it is not completely clear exactly how many attended the theatre performances and concerts, the numerous press reports indicate a wide interest in the programme: wide as in outwith the confines of a cultural avant-garde, and wide as in outwith Weimar. And thereby an interest which tends to validate Gropius’s 1919 claim that “when a Schönberg or a Pfitzner comes to Weimar, the whole world will be aware of the fact”. A Stravinsky, a Busoni or a Hindemith had the same effect.

What is in addition interesting from reading the reports and recollections of those who attended is not only how positively impressed many were by the experience, and lest we forget the likes of a Marianne Brandt joined Bauhaus after having visited the 1923 exhibition, but also the sense of freedom one gets, not only freedom from the realities of early 1920s Germany, but a sense that the tribulations of the Bauhausstreit were briefly forgotten, or as the the journalist Erich Lissner recalls, “many Bauhaus “lehrlinge” and “Gesellen” wore, like myself, a kind of Russian smock and sandals. As a protest against bourgeois civil conventions” and that “In those late summer days, Weimar was not Goethe – but Bauhaus.”22 A point echoed in many of the newspaper reports; a feeling that for a few days in August 1923 Weimar Moderne had the upper hand, not least because, as Gisella Selden-Goth noted in the Prager Tageblatt, Weimar Klassik “cold-bloodedly ignored” the Bauhauswoche.23 It wouldn’t however take long before they regained the upper hand……

Wo sind deine haare, August – Wenskat Orchester

Alongside the teaching and workshops, an important part of Bauhaus life, of the Bauhaus (hi)story, of Bauhaus’s understanding of itself, is and was the extra-curricular and social activities, or as Gropius formulated it in his 1919 Bauhaus Manifesto, the institution strove the “nurturing of friendly contact between Meistern and students outside of the workshops: through theatre, lectures, poetry, music, costume balls”.24 A striving that is best reflected in the Bauhausabende and Bauhausfests.

Staged sporadically throughout the year the Bauhausfests, Bauhaus Parties had, in many regards, their origins in the informal student gatherings at the Ilmschloßchen in Weimar and where the Bauhauskapelle quickly became an established feature, going on to become not only a ubiquitous component of all Bauhaus festivities, but also representing Bauhaus at events throughout Germany.25 Based around Andor Weininger on piano and including amongst its number, and in its differing Weimar and Dessau incarnations, the likes of Xanti Schawinsky, Heinrich Koch or Hanns Hoffmann, sadly no recordings of the Bauhauskapelle exist; however, reading the reminisces of those involved26 it is clear that the sound they generated can be considered every bit as avant-garde and unfettered by prevailing conventions as the artists who performed it, and the public they played to. Lux Feininger likens, as in very loosely likens, the Bauhauskapelle with American Jazz27, a genre that was only just becoming popular in early 1920’s Europe; albeit with the difference that whereas American Jazz was largely influenced by Afro-American traditions, the Bauhauskapelle’s influences were much more the folkloric and vernacular traditions of Eastern Europe and Russia, and therefore a reflection of both the heritage of not just many in the Bauhauskapelle but at the Bauhauses, and also of the oft overlooked influence of Eastern European and Russian folklore on the development of the arts in the late 19th/early 20th centuries.

Although originating in Weimar the Bauhausfests, in many regards, came into their own in Dessau, arguably because there was little else to do in Dessau in the 1920s. And for all came into their own in Dessau under the guidance of Oskar Schlemmer who not only regularly used the Bauhausfests as platforms for, as an extension of, his Theatre workshop, but who was a leading influence on selecting the mottos in context of which the parties were staged; mottos, and the associated costumes, which through their, to paraphrase Stuckenschmidt, “feeling of youthful constructivist upheaval”, are one of the more popular, enduring, images of the Bauhäusler at play. Amongst the most notable Bauhausfests one finds the 1926 “Weiße Fest“, “White Fest”, for which all were asked to dress “Two thirds white, one third colour – in squares, dots or lines”; the 1929 Metallisches Fest at which the staff and students self-created metallic costumes and the metallic decorations celebrated the new industrial age; or December 1925’s Neue Sachlichkeit, an event staged some six months after the opening of the Kunsthalle Mannheim’s exhibition Die Neue Sachlichkeit, an exhibition whose title not only helped establish the term, but whose subtitle, German painting since Expressionism, indicated a shift in the artistic pre-eminence of the period, and by extrapolation the shift at Bauhaus away from the expressionism of early Weimar to the functionalism of Dessau, and a Bauhausfest staged…….. in Halle. A joint Bauhaus/Burg Giebichenstein event and one which helps underscore the friendly relationships that, generally, existed between the two institutions, not least after numerous Bauhäusler, for all the more craft orientated Bauhäusler, switched to Burg Giebichenstein rather than move with Bauhaus from Weimar to Dessau. The music programme for Neue Sachlichkeit featuring in addition to the Bauhauskapelle, Leipzig based combo Wenskat28: nothing to do with the popular card game, but Reinhard Wenskat and his jazz orchestra, one of the earliest professional German jazz orchestras.

Three Burlesques, Op. 8c, Sz. 47 by Béla Bartók

If the Bauhausfests were about Bauhaus and their friends celebrating amongst themselves, the Bauhausabende, Bauhaus Evenings, were much more about Bauhaus extending their activities into the community, and thereby advancing Bauhaus positions and understandings, undertaking, if one so will PR for both the institute and also wider contemporary cultural expressions; but which, as Peter Bernhard notes, were also about reinforcing the Bauhaus ideals amongst staff and students.29

Very much in context of Gropius’s “theatre, lectures, poetry, music, costume balls” principle, the Bauhausabende were staged, at least in early Weimar period, on a more or less weekly basis, and in addition to lectures by external speakers, including, amongst others, Bruno Taut on Glass architecture, Enrique Colás on The functionalism in Anton Gaudís works, and a couple that reflected the more esoteric, for all the Mazdaznan, influence on early Bauhaus Weimar, also featured music, literature and poetry recitals; music/literature/poetry which should be understood beyond pure entertainment and in context of Paul Klopfer’s note that with the Bauhausabende programme Gropius wanted to create an environment where “invited guests from the worlds of literature and music” would be responsible for the musical/literary education of the students.30 And thus, in effect, an informal music/literature programme at Bauhaus.

And also a music/literature programme that, in certain sense, reminds us all very much of Erika Watzdorf’s recollections of pre-Republic Weimar, specifically that, “there was always something going on at the Freytags’, music, theatre, lectures, entertainment of all kinds…”31 The Bauhausabende as a continuation of Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven’s salons? Certainly further support of the “inescapable suspicion that in many regards she [Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven] should have been in favour of Bauhaus.”

But she famously wasn’t.

And thus almost certainly wasn’t at the first Bauhausabende on April 14th 1920 which featured a recital by the poet/performance artist Else Lasker-Schüler; a recital whose controversy should, arguably, have been the nature of Lasker-Schüler’s poetry and performance, was however to be found in a conflict that developed in the course of the evening between “Jewish” and “Germanic” Bauhäusler32; a conflict which tends to underscore, and as previously noted, that the tensions of the period were just as much part of Bauhaus as part of wider society. That the internal conflicts within Bauhaus Weimar led as much to its demise as the external conflicts.

The week after Else Lasker-Schüler’s performance, the pianist Eduard Steuermann performed works by the likes of Mozart, Beethoven, Arnold Schönberg and Erik Satie; the following week seeing readings by Ludwig Hardt from works by, and amongst others, Karl Kraus, Frank Wedekind and Li Tai-Pe; and so the programme continued, the coming years seeing performances and recitals by the likes of the violinist Adolf Busch or the singer Emmy Heim, and readings of, for example, Rainer Maria Rilke’s Marien-Leben33. Whereby a not uninteresting Bauhausabend was that on July 3rd 1920 featuring the Finnish singer Helge Lindberg. An evening to which Gropius invited the Members of the Thüringen Regional Parliament.34 And at which Lindberg performed works by Bach and Händel: a further attempt by Gropius to employ the “connecting element” of Baroque to ease relationships and defuse conflicts in the course of 1920.

One of the last Weimar Bauhausabende was on January 29th 1925 when the Dadaist Kurt Schwitters presented a Märchenabend, Fairytale Evening, at which, amongst pieces such as Auguste Bolte or Schäferspiel, he presented part of his Sonate in Urlauten35, a sound poem as sonata that he begun in 1923 and continually reworked and revised over the next decade. And a performance, we presume, Marianne Brandt witnessed. Although himself never a student at Bauhaus, Schwitters’ was very closely associated with numerous Bauhäusler, for all the likes of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer or Josef Albers, and his work was featured in the third volume of Gropius’s well intentioned, but ill-fated, Neue Europäische Graphik series; while his close association with the institute helps underscore the associations between the Bauhäusler and the Dadaists, and once again, the fact that despite their formal and aesthetic differences, Dada, Surrealism and International Modernism, weren’t that far removed from one another.

Following the move to Dessau the Bauhausabende as they had existed in Weimar (largely) ceased, but regular extra-curricular cultural events remained a feature of Bauhaus life, including a production of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition staged and directed by Wassily Kandinsky in Dessau’s Friedrich-Theater on April 4th 1928, and a concert on October 12th 1927 (possible October 14th 1927) featuring Zoltán Kodàly…………. and Béla Bartók! Who, and amongst other works, played his first series of Romanian Christmas Carols, his Piano Sonata Sz. 80, and his 3 Burlesques36

We presume Marianne Brandt was there. And that she enjoyed herself immensely.

The above is, can only be, but the briefest of explorations of the connections between music and Bauhaus, and we’d urge you all to do more research and exploring on your own; similarly the Radio smow Bauhaus playlist cannot hope to do full justice to the varyifold relationships between music and Bauhaus, not least because of the amount of material that doesn’t exist, never existed. Quite aside from the (near) silence that accompanies contemporary reflections on Bauhaus theatre, the non-recordings of Paul Hindemith’s rewritten Marienlieder and Ernst Krenek’s withdrawn 1. Concerto Grosso as performed during the Bauhauswoche, or the long since lost original music composed by Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt and Lonny Ribbentrop for the Mechanische Kabarett, one has (so far we can ascertain) no recordings of the many Bauhäusler who played music: for example, from Paul Klee whose professional violin recitals kept him fed and watered until he could make a living from his art; from Lyonel Feiniger who played violin and organ, composing in the 1920s thirteen fugues of his own, which he preformed at a Bauhausabend on October 30th 1922; or from the Bauhauskapelle whose recordings resonate in their absence. If ever we are fortunate enough to be granted three wishes, one would be an authentic live recording of the Bauhauskapelle.

In addition to the above listed works the Radio smow Bauhaus Playlist features a selection of music associated with/of relevance to the Bauhauses⇓⇓⇓: and all, as the 1920 Morgenfeier was intended to be, sandwiched between some triumphant Bach.

The Radio smow Bauhaus Playlist, and all Radio smow playlists can be found on the smowonline Spotify page.

More inspiration?

External content is linked here. If you want to see the content once now, click here.

The Radio smow Bauhaus Playlist: A quick guide

Johann Sebastian Bach, Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major, BWV 552: intended to be part of the planned Morgenfeier in the Deutsches Nationaltheater Weimar on March 21st 1920

Arnold Schönberg, Pierrot Lunaire: presented in Weimar in a, from Bauhaus co-organised, performance on October 27th 1922

Ferruccio Busoni, Perpetuum mobile, BV293: performed by Egon Petri in Weimar as part of the Bauhauswoche, August 18th 1923

Wenskat Orchester, Wo sind deine haare, August: the Wenskat Orchester performed at the joint Bauhaus/Burg Giebichenstein party Neue Sachlichkeit in Halle on December 4th/5th 1925. Unsure if this was actually played, but Wenskat recordings are rare….

Béla Bartók, Three Burlesques, Op. 8c, Sz. 47: performed by Bartók at Bauhaus Dessau on October 12th 1927 (possible October 14th 1927)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Piano Sonata No. 8 in A minor, K 310: performed by Eduard Steuermann at the second Bauhausabend, 21.04.1920

Else Lasker-Schüler, Fortissimo, Was hat die Lieb mit der Saison zu tun, Overture, Mein Tanzlied, Vollmond: At the first Bauhausabend on April 14th 1920 Else Lasker-Schüler performed works from her Hebräische Balladen, Der Scheik & Abigail I von Theben, but as we can’t find recordings of those, and felt we should include some Else Lasker-Schüler, these stand as proxy.

Johann Sebastian Bach, Sonate for Violin and Piano in G major, Adagio, BWV 1019: used by Paul Klee for a class in discussing the creation of art from music, and the similarities of the two genres.

Georg Friedrich Händel, Il trionfo del Tempo e della Verita: Helge Lindberg sang from Il trionfo del Tempo e della Verita at the 8th Bauhausabend on 03.07.1920 Unsure as to what exactly was sung, works here as representative of the work.

Ferruccio Busoni, 5 kurze Stücke zur Pflege des polyphonen Spiels: The first three were premiered in Weimar by Egon Petri as part of the Bauhauswoche, August 18th 1923

Johann Sebastian Bach, Sonata No 1 in G Minor, BWV 1001: performed by Adolf Busch as part of the Bauhausabende series on 01.07.1920

Béla Bartók, 2 Elegies, Op. 8b, Sz. 41: performed by Bartók at Bauhaus Dessau on October 12th 1927 (possible October 14th 1927)

Claude Debussy, L’isle joyeuse: performed by Eduard Steuermann at the second Bauhausabend, 21.04.1920

Ferruccio Busoni, Toccata. Preludio – Fantasia – Ciaccona, BV 287 : performed by Egon Petri in Weimar as part of the Bauhauswoche, August 18th 1923

Ferruccio Busoni, Prélude et étude en arpèges, BV 297: premiered in Weimar by Egon Petri as part of the Bauhauswoche, August 18th 1923

Kurt Schwitters, Die Sonate in Urlauten: performed by Schwitters, in part, in context of a Bauhausabend in Weimar on January 29th 1925

Modest Mussorgsky, Pictures at an exhibition: Wassily Kandinsky staged and produced a performance of Pictures at an exhibition with a mobile scenography in the Friedrich-Theater Dessau on April 4th 1928

Béla Bartók, Piano Sonate, Sz. 80: performed by Bartók at Bauhaus Dessau on October 12th 1927 (possible October 14th 1927)

Max Reger, Preludes and Fugen Op,117, No4: performed by Adolf Busch as part of the Bauhausabende series on 01.07.1920

Georg Friedrich Händel, Mirth, Admit me of thy crew, Let me wander, not unseen, Hence! Loathed melancholy: Helge Lindberg sang passages from L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, HWV 55 at the 8th Bauhausabend on 03.07.1920 Unsure as to what exactly was sung, works here as representative of the work.

Arnold Schönberg, 3 Klavierstücke Op.11: performed by Eduard Steuermann at the second Bauhausabend, 21.04.1920

Zoltán Kodàly, 7 piano pieces, Op.11, No. 4 Epitaph Rubato: performed by Kodàly at Bauhaus Dessau on October 12th 1927 (possible October 14th 1927)

Igor Strawinsky, Die Geschichte vom Soldaten: performed by musicians from the Weimarischen Staatskapelle alongside Karl Ebert (Vorleser), Fritz Odemar (Soldat), Hermann Schramm (Teufel) & Ilse Petersen (Prinzessin), under conductor Hermann Scherchen in Weimar as part of the Bauhauswoche, August 19th 1923

1. Marrianne Brandt, Brief an die junge Generation, in Eckhard Neumann [ed.], Bauhaus und Bauhäusler. Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse, DuMont Buchverlag, Köln, 1985

2. Volker Wahl, Das Programm für eine nicht stattgefundene Morgenfeier des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar im März 1920, Weimar–Jena:Die große Stadt, 3/2, 2010, 158–166

3. Wolfgang Rathert, Kult und Kritik. Aspekte der Bach-Rezeption vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, in Michael Heinemann and Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen [eds.], Bach und die Nachwelt Band 3 1900-1950, Laaber-Verlag, Laaber, 2000

4.Martha Ganter, Musikleben am Staatlichen Bauhaus in Weimar, Weimar–Jena:Die große Stadt, 5/3, 2012 182–190

5.Lyonel Feininger, Letter to Julia Feininger, 11.02.1922, in June L. Ness [ed.], Lyonel Feininger, Allen Lane, London, 1975

6. Susanne Fontaine, Ausdruck und Konstruktion. Die Bach-Rezeption von Kandinsky, Itten, Klee und Feininger, in Michael Heinemann and Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen [eds.], Bach und die Nachwelt Band 3 1900-1950, Laaber-Verlag, Laaber, 2000

7. Paul Klee. Beitrage zur bildnerischen Formlehre, in Paul Klee, Kunst-Lehre: Aufsätze, Vorträge, Rezensionen und Beiträge zur bildnerischen Formlehre, Verlag Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1987, 148ff

8. Willy Rotzler [ed.], Johannes Itten. Werke und Schriften, Orell Füssli Verlag, Zürich, 1972, page 95

9. Letter to Anna Höllering, 31.12.1918, in Willy Rotzler [ed.], Johannes Itten. Werke und Schriften, Orell Füssli Verlag, Zürich, 1972, page 62

10. Friedrich Teja Bach, Johann Sebastian Bach in der klassischen Moderene in Karin v. Maur [ed], Vom Klang der Bilder. Die Musik in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, Prestel, München 1985

11. Martha Ganter, Musikleben am Staatlichen Bauhaus in Weimar, Weimar–Jena:Die große Stadt, 5/3, 2012 182–190

12. Jelena Hahl-Koch [ed.], Arnold Schönberg – Wassily Kandinsky: Briefe, Bilder und Dokumente einer aussergewöhnlichen Begegnung, Residenz Verlag, Salzburg, 1980, 19-20

13. Dieter Bogner, Musik und bildende Kunst in Wien, in Karin v. Maur [ed], Vom Klang der Bilder. Die Musik in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, Prestel, München 1985

14. Felix Klee, Meine Erinnerungen an das Bauhaus Weimar, in Eckhard Neumann [ed.], Bauhaus und Bauhäusler. Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse, DuMont Buchverlag, Köln, 1985

15. Gertrud Grunow, Der Aufbau der lebendigen Form durch Farbe, Form, Ton, in Staatliches Bauhaus, Weimar 1919 – 1923, Bauhausverlag, Weimar-München, 1923, 20-23

16. Jelena Hahl-Koch [ed.], Arnold Schönberg – Wassily Kandinsky: Briefe, Bilder und Dokumente einer aussergewöhnlichen Begegnung, Residenz Verlag, Salzburg, 1980, 21-22

17. Linn Burchert, Gertrud Grunow (1870 – 1944). Leben, Werk und Wirken am Bauhaus und darüber hinaus https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/handle/18452/20284 (accessed 03.05.2020)

18. Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, Neue Musik, Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 1981

19. Walter Gropius, letter to Ernst Hardt 14th April 1919, reprinted in Volker Wahl, Das staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar: Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919-1926, Böhlau Verlag, Köln Weimar, 2009

20. Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, Musik am Bauhaus, Hans Maria Wingler [ed.], Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, 1978/79

21. Walter Gropius, Das Ende der Bauhausausstellung, Allgemeine Thüringische Landeszeitung Deutschland, Nr 275, 6th October 1923, reprinted in Volker Wahl, Das staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar: Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919-1926, Böhlau Verlag, Köln Weimar, 2009

22. Erich Lissner, Rund ums Bauhaus 1923, in Eckhard Neumann [ed.], Bauhaus und Bauhäusler. Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse, DuMont Buchverlag, Köln, 1985

23. Gisella Seidon-Goth, Das andere Weimar, Prager Tageblatt 26th August 1923, available at http://open-archive.bauhaus.de, Walter Gropius: Zeitungsarchiv. Ausstellung Bauhaus Weimar 1923. Mappe II

24. Walter Gropis, Entwurf der Satzungen des Staalichen Bauhauses zu Weimar vom April 1919, reprinted in Volker Wahl, Das staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar: Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919-1926, Böhlau Verlag, Köln Weimar, 2009

25. Xanti Schawinsky mentions performances in Hannover, Halle, Berlin and Magdeburg, Xanti Schawinsky, metamorphose bauhaus, in Eckhard Neumann [ed.], Bauhaus und Bauhäusler. Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse, DuMont Buchverlag, Köln, 1985

26. See, e.g. the various notes in Eckhard Neumann [ed.], Bauhaus und Bauhäusler. Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse; Lux Feininger, Die Bauhauskapelle und Evy Weininger, Letter tu Lux, 22nd November 1991, both in Bothe et al [eds], Das frühe Bauhuaus und Johannes Itten, Verlag Gerd Hatje, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1994, 374 – 380; Thomas Schinköth, Vulkanisches Gelände im Meere des Spießbürgertums: Musik und Bühne am Bauhaus, in Günter Eisenhardt [ed]. Musikstadt Dessau. Kamprad Verlag, Altenburg, 2006; Die Bauhaus-Kapelle in Andi Schoon, Die Ordnung der Klänge. Das Wechselspiel der Künste vom Bauhaus zum Black Mountain College, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld https://www.transcript-verlag.de/978-3-89942-450-8/die-ordnung-der-klaenge/?number=978-3-89942-450-8 (accessed 03.05.2020)

27. Lux Feininger, Die Bauhauskapelle, in Bothe et al [ed.s], Das frühe Bauhuaus und Johannes Itten, Verlag Gerd Hatje, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1994,

28. Halle und die Moderne, Stadt Halle (Saale) PDF available via http://www.halle.de/VeroeffentlichungenBinaries/787/1204/halle-und-die-moderne.pdf

29. Peter Bernhard, Einleitung, in Peter Bernhard [ed] Bauhaus Vorträge. Gastredner am Weimarer Bauhaus 1919-1925, Neue Bauhausbücher, Band 4, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin, 2017

30. Paul Klopfer, I. Lebenslauf: Entwicklung und Bestätigung, NL paul Klopfer SN11/301, quoted in Peter Bernhard [ed] Bauhaus Vorträge. Gastredner am Weimarer Bauhaus 1919-1925, Neue Bauhausbücher, Band 4, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin, 2017

31. Erika von Watzdorf-Bachoff, Im Wandel und in der Verwandlung der Zeit: Ein Leben von 1878 bis (1963),Reinhard R Doerries (Ed), Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart, 1997

32. Peter Bernhard, “Frau Lasker-Schüler hauue uns mit ihren Staccato-Versen völlif im Bann”, in Peter Bernhard [ed] Bauhaus Vorträge. Gastredner am Weimarer Bauhaus 1919-1925, Neue Bauhausbücher, Band 4, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin, 2017

33. Chronologisches Verzeichnis der Gastveranstaltungen am Weimarer Bauhaus, in Peter Bernhard [ed] Bauhaus Vorträge. Gastredner am Weimarer Bauhaus 1919-1925, Neue Bauhausbücher, Band 4, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin, 2017

34. Mitteilung über eine Einladung zum Bauhausabend an die Landtagsabgeordneten, reprinted in Volker Wahl, Das staatliche Bauhaus in Weimar: Dokumente zur Geschichte des Instituts 1919-1926, Böhlau Verlag, Köln Weimar, 2009 335

35. Isabel Schulz, “Märchen unserer Zeit”. Kurt Schwitters als Votragskünstler am Bauhaus, in Peter Bernhard [ed] Bauhaus Vorträge. Gastredner am Weimarer Bauhaus 1919-1925, Neue Bauhausbücher, Band 4, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin, 2017

36. Programm für die 11 Veranstaltung des “Kreis der Freunde des Bauhauses”, CHB – Collegium Hungaricum Berlin Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/collegiumhungaricumberlin/photos/a.351633731407/10156644885511408/?type=1&theater (accessed 03.05.2020)

Tagged with: Bach, Bauhaus, Dessau, Radio smow, Weimar