smow Blog Design Calendar: April 30th 1993 – Opening of Citizen Office at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein

With the exhibition Citizen Office the Vitra Design Museum staged not only their first conceptual, research based, exhibition, but also one of the first museal reflections on “the world of the office”.

Reflections which not only pointed towards new directions and understandings then, but which offer insights and lessons for today…….

The ubiquity of office work in our contemporary society belies the relative youth of “the office” as a physical space, historically an “office” was a function: an Office of State, an Office of the Church, and thus a person and the duties attached to that person, while the common origin of the French “bureau” and German “Büro” can be found in the Old French burel, a coarse cloth which covered a table/desk in a place of official business, and which over time became that desk/table before being extrapolated to mean the room in which the desk/table stood. Similarly the understanding of “office” evolved to mean the place where the work of an Office was undertaken, before in the course of the political, economic and social changes of the nineteenth century, for all in context of, for example, advancing industrialisation, the shift from monarchies to parliamentary democracies, an increasing mobile global community, growing international trade and the associated development of the financial, commercial, legal and governmental structures necessary for such, office/bureau/Büro adopted to their contemporary understanding as general places of non-manual, desk bound, work.

The development of our understanding of the term office/bureau/Büro contains however several dimensions; as a place of work the understanding of office/bureau/Büro has changed only little since it first emerged in the 18th century, and in many regards is the least interesting dimension. Much more interesting is the developments in our understandings of “office” in context of its relationship to individuals and society. For example, only very few note and appreciate that the “-cracy” an the end of “Bureaucracy” is the same as that at the end of “Autocracy”, “Aristocracy” or “Democracy”: Democracy – rule/authority of the people. Bureaucracy – rule/authority of the Office. Which is what one had in the days of the Office of State or burel. And was something one had little choice but to accept. However as society developed, became more complex, more enlightened and reformed, so to did the nature of the office: whereas, for example, the large commercial offices of the 19th century were organised very much inline with feudal systems and prevailing class separation, throughout the course of the 19th and 20th centuries the office/bureau/Büro became increasingly open and responsive institutions, both internally and externally.

Remained however a place of structures, processes and controls, remained, if one so will, a local manifestation of the social contract; but became, along with wider society, much less regimented, less hierarchical, occasionally a little more colourful. And for all remained a reflection of contemporary society, its attitudes, understandings, positions. Or perhaps better put, an echo of contemporary society; changes in office culture invariably lagging behind changes in wider culture and rarely being an exact recitation.

And while society’s attitudes, understandings and positions are prone to gradual developments, there are moments of more sudden change, such as the late 1980s whose rapid social, cultural, political, economic, technical, et al evolutions and revolutions harbinged the coming of a new office age.

A coming office age Citizen Office sought to approach an understanding of.

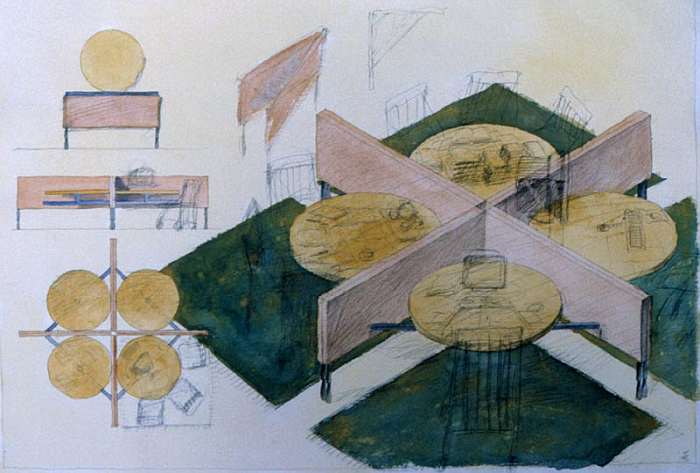

Sketch by Michele De Lucchi, with Geert Koster of the desk constellation for the flexible office concept for Citizen Office, Vitra Design Museum

In many regards Citizen Office arose as the logical merging of two paths: in the late 1980s Vitra began the, somewhat unfortunately monickered, project “Office Dreams – Dream Offices”, which saw them cooperate with designers on developing concepts for “a more attractive, sensual and social office”1, a project largely driven by the, then, Vitra CEO Rolf Fehlbaum, and as a targeted response to evolving realities. At around the same time the Vitra Design Museum were in talks with Ettore Sottsass about developing a monographic exhibition, an exhibition which was intended to include reflections by Sottsass on “The Hedonistic Office”, a section of the exhibition Sottsass suggested making the focus, a suggestion the Vitra Design Museum accepted and which saw Michele De Lucchi, Andrea Branzi and Rolf Fehlbaum brought in as co-collaborators in a process that, and despite its origins, wasn’t planned to necessarily end in an exhibition. And certainly not in office furniture. Far less dreams of such.

Much more the quartet began a discussion staged over five meetings throughout the course of 1992, a discussion which, essentially, saw them approach “the world of the office” as a so-called Wicked Problem, a problem with no definitive answer, just answers with differing degrees of incompleteness, and which they approached through deliberations less on the office itself as on the function of the office, the relation of the office to employee, of employee to office, of office to society, to technology, to urban spaces, etc, and, as Andrea Branzi notes, a discussion undertaken with the intention of “highlighting contradictions”2. Contradictions between, for example, contemporary office realities and contemporary office workers demands, between contemporary office life and contemporary non-office life.

A discussion which for all it that it is very familiar today, wasn’t then. Was then very new. And a discussion that not only involved three of the leading protagonists of Italian Radical, Anti, Design, but in many regards was a discussion enabled by post-War developments in design understandings originating in Italy, for all the Italian contribution to both the widening of the term “design” and also to the development of understandings of “function” as being both more than physical and more than a direct linear relationship. And thus not something form can necessarily follow.

Although undertaken as a theoretical exercise, a physical manifestation, an exhibition, did result: Sottsass, De Lucchi and Branzi each creating an office space as a reflection of their understandings and interpretations of the discussions; spaces that Andrea Branzi underscores weren’t to be understood as individual projects, rather as, “varying landscapes that unite in their differences”, specifically: the flexible office, the nomadic office, the vertical office.

In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue* Rolf Fehlbaum notes that “De Lucchi was keen to reminded us that we were considering real problems”, and for De Lucchi the most real problem was that contemporary offices “were not flexible enough”3 His answer? A system of desks, storage units and chairs that were transformable, variable, whose use, function, wasn’t strictly defined but was to be defined and discovered in practice, and continually re-discovered and re-defined, and that not least because, as he opined, “you can never fully approach the real life in an office, can never approach that which actually happens in an office.” And so don’t try. Leave space for that reality to develop.

Similarly Ettore Sottsass was the opinion that the office must “become a flexible instrument to correspond to the psychological nomadism of contemporary individuals”, and thus, not uninterestingly, an understanding of nomadism as of the mind, and not the physical nomadism than became so popular with designers a few years later. To this end he created with his nomadic office an office that, in contrast to the reserved, unassuming, character of De Lucchi’s flexible office, is/was very much what one might expect of an Ettore Sottsass: bright, colourful, squint, poppy. And with a large tent in the middle. On the one hand an easy metaphor for transiency, flexibility, nomadism, but also a room-within-room that could serve a myriad functions, be that for business or pleasure, and which, for all through its combination with the wider furnishings, prevents any easy association of the space with toil, burden or institution.

Whereas the proposals of Sottsass and De Lucchi, and despite their contentual distancing from the then office conventions, and despite Sottsass’s tent, are/were very much offices of the familiar desks, chairs, storage units, et al, Andrea Branzi’s vertical office sought to illustrate the evolving changes and understandings of the office through a new office scenography, creating, in effect, work pods, thin wooden frames housing work spaces, but also cooking and sleeping spaces, and thus underscoring one of the recurring themes in Citizen Office, the increasing blurring of the border(s) between home and office, or as Branzi phrased it, “the idea of “located work” is becoming weaker, a process of transformation of social behaviour patterns is underway. The office extends into the city, and the city in turn spills over into the office.” A process in which emergent technology was to play, was playing, a central role, opening up new possibilities, for all information transfer and communication possibilities within the office and between an individual and an office.

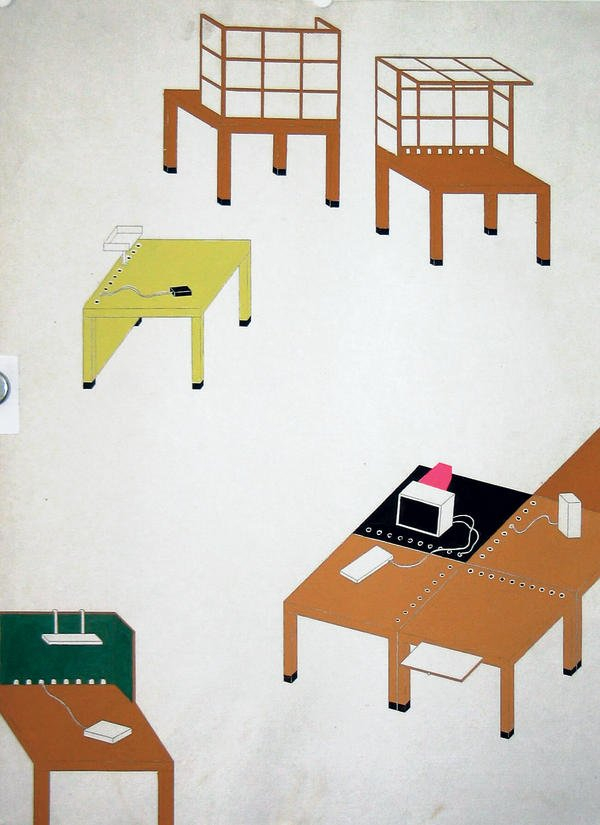

And something reflected throughout the three offices in a collection of speculative product proposals developed by the quartet in cooperation with Siemens and including, and amongst other preposterous flights of fancy: the Bildtelefon, a device which allowed for video telephone calls; the Dataspeicher, a mobile device which contained information in digital format and which could be connected to any computer to allow access to the information; or Power Books, quadratic digital devices based formally on paper books and which enabled the user to “lean back and read the screen like a book”. Imagine! Impossible! Amongst all this newness one notes that the telephone receiver retained its traditional banana-esque morphology because, “it is a well understood icon and thus aids the adaption to wireless technology”, and thus underscoring the value and function of the skeuomorph in product design.

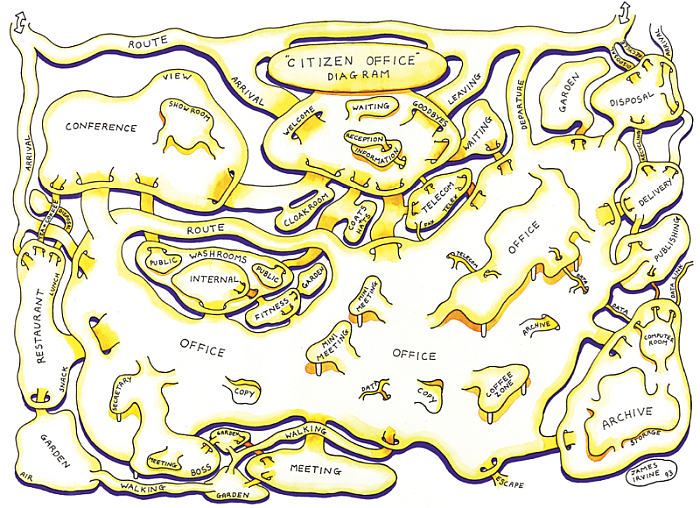

The uniting of the varying landscapes being reinforced by graphic depictions and visualisations of the discussions and understandings as sketched by James Irvine, who in addition had proposed the name Citizen Office, while the evolving acoustics of the office landscape were considered in a sound installation by media artist Walter Giers. Which we’ve not heard. But are very keen to.**

Visualisation of part of Ettore Sottsass’s nomadic office concept for Citizen Office, Vitra Design Museum

Reflecting on Citizen Office with the benefit of 27 years hindsight one is taken less with the number of statements and positions that have become, more or less, reality – proving any future vision was correct is easy with enough hindsight, just ask Nostradamus – but much more by the degree to which our contemporary flexible working, networking, endless availability was understood in the early 1990s, even though the necessary technology was in its infancy: the first GSM mobile phones, for example, were launched in 1992 while the World Wide Web was still, essentially, a research project. Yet the path we have followed since 1993 is, largely, that discussed in Citizen Office. And thus the question arises if that path was the correct one? The optimal one? Given that all was new, all was open, all was possible. Or put another way, when, for example, Andrea Branzi wrote, “the individual, equipped with mobile devices, can be reached anywhere, anytime, around the clock”, or, “Private and work life are becoming increasingly mixed …” were there not an awful lot of alarm bells ringing. Very, very loudly. For all against the background of the brief discussion in the exhibition catalogue on the shortcomings and negative consequences of both Taylorist optimisation and the Japanese inspired Company Wide Quality Control approach. Why would permanent availability and a blurring of home/office not contain shortcomings and not lead to negative consequences? Was permanent availability and a blurring of home/office not predestined to become the machinery in which a 21st century Charlie Chaplin would find himself entangled…….?

But then, as we noted above, the quartet approached the question of the office as a Wicked Problem, one with no perfect answer, one in which all answers are inclined to create new problems, and thus was permanent availability and a blurring of home/office the unavoidable symptom of the benefits mobile, networked technology brought both employer and employee? Was permanent availability and a blurring of home/office to be understood as the basis of the office social contract in a networked, digital age, the counterbalance for the loosening of the physical binding to the office and increased worktime flexibility? Or is it not the office’s fault, is the office not simply echoing wider society? Was a blurring of home/office simply a natural consequence of permanent social availability: was the price to pay for being permanently available for friends and family, being permanently available for work, and thus a blurring of home/office? And what can such reflections teach us about our contemporary emergent technology? Do we understand the inherent shortcomings and negative consequences? Do we understand they are inherent? Are there are alarm bells ringing? Why not?

In addition, reflecting on Citizen Office with the, for want of a better word, benefit, of our contemporary realities allows one a differentiated insight into a central theme in the Citizen Office discussions: the social function of the office, the office as a place of social interaction, of human intercourse. And the extrapolated understanding that if offices echo contemporary society then the life that occurs within the office must culturally be on a par with the expectations of employees. Which arguably is one of the reasons the infamous cubicles failed, they disabled the social functionality of an office at a time of increasing social mobility and diversification, were based on values not repeated outwith the office, and thereby disconnected the office space from all other spaces and in doing so alienated office workers from the office and thereby their work.

And home office?

We’d argue is largely the same in that it disrupts, disallows, the social function of the office. If one so will, with home office the cubicles are not only much further apart, but don’t have a communal water cooler that can serve as an occasional social oasis on the journey through the working day. And similarly must lead to an alienation of office workers because the social function of the office is absent.***

And thus the current levels of enforced home office could see the understanding of the social function of the office come more into focus; could see an increased understanding that the office and the home aren’t interchangeable, regardless of how similarly one furnishes the two; an increased understanding that the term “home office” relates purely to work, which isn’t the exclusive function of an “office office”, and that thereby the office could, should, stop being primarily associated with work.

Which would be a move on from Citizen Office: for all their considerations on the the social function of the office, the three Citizen Offices remain primarily places of work, that understanding of “office” that has accompanied us since the 18th century. And which in many regards is becoming ever less interesting. Not least because contemporary technology means that while the work undertaken in offices remains a challenge one must learn to master, and continue learning as the challenge evolves, much of the actual process of office work runs by itself in the background; it’s not so much the technology that has become integrated in the office, as that the office has become integrated in the technology, and that’s why you can work from home. And why managers can arrange so many meetings. But which also leaves space for the social, cultural, human, function of the office.

A phrase we keep coming back to when considering Citizen Office is Sottsass’s “psychological nomadism”, a phrase which, and as with much of Sottsass, we don’t really fully understand; but which, for us, on the one hand implies a rejection of the monotony of office work, and on the other an insatiable curiosity, be that for new information, understandings, experiences, challenges, learning, emotions, opinions, stimuli, etc. A curiosity that was once the preserve of a privileged few but is now near universal. A curiosity new technology helps feed. A curiosity that can help us establish the fairer society we all claim to want. And a curiosity that the complexity of an office is well placed to both respond to and nurture. And which it can, if we can free the office from its understanding as primarily a place of work.

And where does that leave the coming office age…….?

A Citizen Office Chair, and in the background a black/turquoise filing cabinet, by Ettore Sottsass, as seen at Vitra – Typecasting, Milan Design Week 2018

……we no know.

But then no-one does.

Certainly the Citizen Office quartet didn’t, nor claim to, all were clear that wherever their discussions took them it wouldn’t be an answer but rather a transitory moment “on the threshold between criticism of existing convention and, as an option, examples, of a future office landscape”. An understanding of which caused Rolf Fehlbaum to note that the quartet wanted to pick up their deliberation on “work and life in the office” at a later date, and “maybe realise Citizen Office 2 towards the end of the decade.” They didn’t, but three decades later it is certainly a subject in need of revisiting.

The ever increasing rise in home and decentralised working, increasing blurring of home/office, ever more prevalent permanent availability, ever more monotone, formulaic, formalistic, office furniture programmes and the ever more apparent shortcomings and negative consequences therein, would inevitably have led to an urgent need to reconsider “work and life in the office”, SARS-CoV-2 has arguably only accelerated that process, forcing as it did/does many who otherwise wouldn’t work from home, would never choose to work from home, to do such. And while we are certain, without actually knowing, that there are a great many office workers keen to get back to the office, we are equally certain that there are just as many facility managers and finance directors measuring the savings that could be made by keeping everyone at home, and just as many environmental scientists noting with delight the improving urban air quality through reduced commuting. The social demands of the individual against the economic demands of the institution against the ecological requirements of us all.

Contradictions that leaves us in need of “an option, examples, of a future office landscape”

In October, all going to plan, Europe’s largest office furniture fair, Orgatec, will be staged in Cologne, and where many such examples will be presented, in which context one imagines that near all manufacturers are currently rapidly reworking their portfolios to include more room dividers, desktop screens, touch-free mechanics, et al… and a lot less of the semi-enclosed acoustic meeting pods that have been so popular in recent years. Parallel Vitra will, as we predicted in 2016, stage their own event in Weil am Rhein, where they will present their latest proposals for office culture, their latest reflections in conjunction with their roster of designers, reflections staged at the interface between Citizen Office and “Office Dreams – Dream Offices”.

However, the current realities are also an opportune moment to reflect in greater depth, from a more theoretical, abstract, conceptual, longer, perspective than has been the case in recent years on the Wicked Problem of “work and life in the office”, not just in context of reflections on the future consequences of developments of recent months, but, and as with Citizen Office, in context of our rapidly developing technology, for all artificial intelligence, robotics, virtual networks etc, for such will define the future of office work, will define both the new shortcomings and negative consequences of office work and also the new advantages, for example, of shorter working weeks and increased flexibility, and thus the evolving office social contract. But for all deliberations with Citizen Office‘s “renunciation of a commercial intention”, that “unmerciful censor of all ideas”, and simply through a focus on “the world of the office” which, and as we all understand much better today, not least through the deliberations of Sottsass, Branzi, De Lucchi and Fehlbaum, is an echo of the world outwith the office, a world of inherent contradictions that need to be brought to the fore and, when imperfectly, aligned.

1. Martina Arnold, Von der Amtsstube zum Bürotel, taz, 17.04.1993 https://taz.de/!1620388/ (accessed 29.04.2020)

2. and all further quotes unless stated, in Uta Brandes; Alexander von Vegesack [Ed], Citizen Office: Ideen und Notizen zu einer neuen Bürowelt, Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 1994

3. https://www.archive.amdl.it/en/index.asp?f=/en/archive/view.asp?ID=305&h=archive (accessed 29.04.2020)

* Uta Brandes; Alexander von Vegesack [Ed], Citizen Office: Ideen und Notizen zu einer neuen Bürowelt, Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 1994. Although we’re calling it a catalogue it is more an accompanying publication, released as it was a year after the exhibition.

** The current realities have curtailed much background research for this post, not least the fact that a lot of possible sources are in the, currently inaccessible, cellar of the Vitra Design Museum. However, we have a crack team of researchers standing by and as soon as it is safe and responsible to do so will enter that cellar and extract all that is relevant and interesting. Having done so we will then bring a Reprise post, hopefully with a lot more photos. And having finished in Weil am Rhein will travel to Birsfelden and extricate the “Office Dreams – Dream Offices” documentation from Vitra’s cellar…..

*** We fully understand that there are those who prefer home office to office office. Us, for example. We have such an acute office allergy we have based ourselves just beyond the edge of the known universe to minimise the risk of every having to work in an office. However, we’d argue that a great many of those who regularly work from home do so either (a) as a compromise, for example, for reasons of family management, and that they would much rather work in an office office or (b) because they are solo self-employed and have neither colleagues nor an office office; whereby we’d argue that the existence and success of co-working spaces supports our position, indicating as it does that many solo self-employed want an office office. And which brings us back to a previous discussion about not creating offices that look like the places where freelancers work, but understanding why freelancers work where they do. And that they possibly don’t want to work where they do. But, and again without any evidence, we are certain that the greater many of those forced in recent weeks to work from home, really aren’t enjoying the experience. Although we do know people who are.

Tagged with: #officetour, Andrea Branzi, Citizen Office, Design Calendar, Ettore Sottsass, James Irvine, Michele De Lucchi, milestones, Rolf Fehlbaum, Vitra, Vitra Design Museum