It is perhaps indicative of the differing receptions to and estimations of design in the former West Germany and the former East Germany that while Dieter Rams' Ten Principles of good design are revered as if cast in stone, Karl Clauss Dietel's Five Big Ls of good design have barely seen the light of day since November 1989.

A popular focus on the former West which tends to popular understandings of design from West Germany as being valid and authentic and laudable, while design from East Germany is reduced, denigrated, to cartoon Ostalgie.

With karl clauss dietel. die offene form Walter Scheiffele and Steffen Schuhmann allow one to approach more probable understandings both of the (hi)story of design in the former East Germany and of Karl Clauss Dietel's position in the (hi)story of design, and in doing so stimulate a re-evaluation of the receptions to and estimations of design in and from East Germany.......

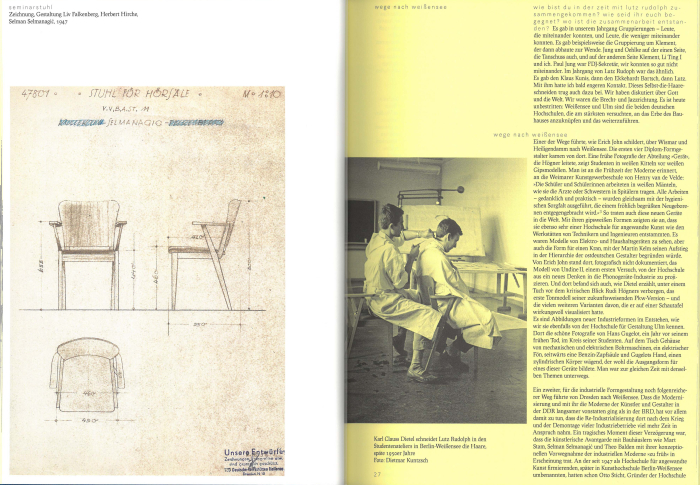

Born on October 10th 1934 in Reinholdshain, Sachsen, Karl Clauss Dietel initially trained as a machine fitter and vehicle body constructor, before in 1956 enrolling at the Hochschule für angewandte Kunst Berlin-Weißensee to study Formgestaltung, Design.3

Which is where die offene form begins, with a chapter that sets up the format of the book: a chapter that opens with an interview with Karl Clauss Dietel4 before moving into an essay by Walter Scheiffele which extends the scope and range of the chapter's themes, which brings in other protagonists, and which moves the chapter's discussion away from Karl Clauss Dietel and into the wider economic, political, cultural, et al contexts in which design existed in the DDR.

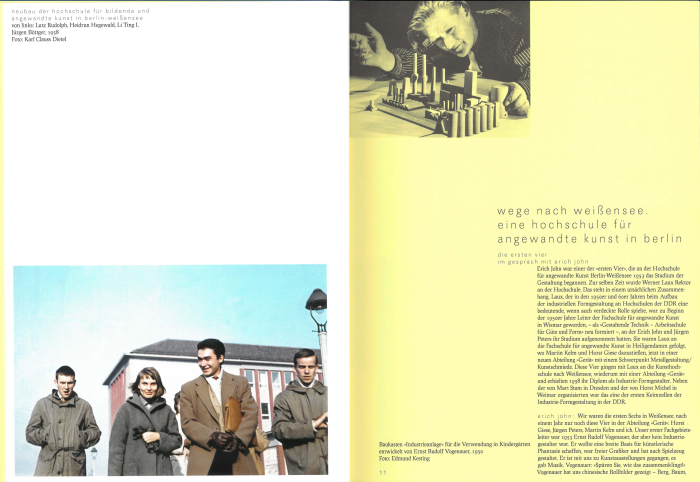

An opening chapter which, amongst other subjects, discusses the Formalism Debate and associated disputes and demonisations that defined, complicated, the establishment of industrial design in the DDR; an opening chapter which introduces numerous important individuals in the development of design in the DDR, individuals who are regularly encountered throughout die offene form including, and amongst many others, Erich John, Martin Kelm or Lutz Rudolph, the latter with whom Dietel worked closely throughout his career and is inextricably linked; an opening chapter which confirms the "permeability" of the 1950s Klara Nemeckova spoke about from the exhibition German Design 1949 - 1989 at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden, the reality that in the 1950s, before the Wall, Berlin was still relatively open, or as Dietel recalls of his student years, "we lived in DDR reality, we acknowledged it, and partially withdrew from it ... every week or two, we were in West Berlin, on Kurfürstendamm. ‘Braun’ had a store there, there was ‘Knoll International’, works by Alvar Aalto and by Saarinen .... When a new Braun product was launched, we saw it eight days later ... We knew every house in the Hansaviertel [Interbau '57 International Building Exhibition]....".56

And an opening chapter which allows insights into the background of das offene Prinzip, the Open Principle, that position that is so central to Karl Clauss Dietel.

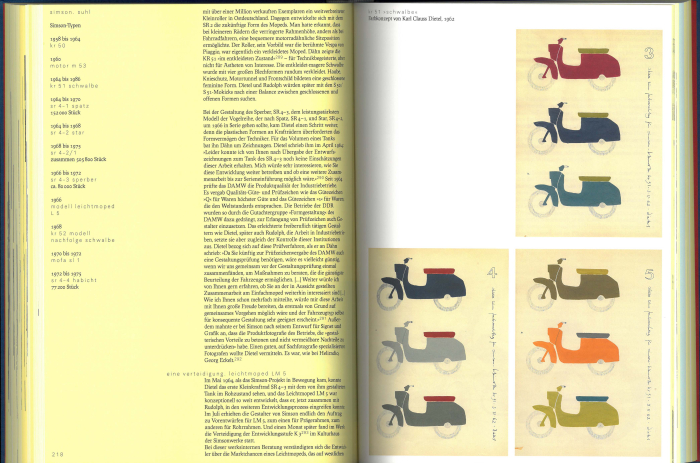

A principle that, and simplifying more than we're happy with, decrees that objects should be designed so that the user can not only understand the internal relationships, but for all designed so that the user is empowered, encouraged, to replace individual components as and when required and thereby extend the lifetime of the object; a principle that is very much the opposite of planned obsolescence; a principle closely related to the Gebrauchspatina, the Patina of Use, a further key principle in Karl Clauss Dietel and which extols an emotional functionality as a key component of an object; a principle we discussed in our post from Simson, Diamant, Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, and to which we refer you dear reader.

And a principle which die offene form allows one to understand as having arisen from several directions: from the DKW RT 125, a motorbike developed in the 1930s in Zschopau near Chemnitz, and which greatly informed Dietel and Rudolph's Simson Mokick, that work which so elegantly expresses das offene Prinzip; from the idea of Der Nutzer als Finalist, the principle that the end-user should decide on the formal expression, the layout and the nature of use, et al, and of which the MDW shelving system by Dietel's contemporary Rudolf Horn is perhaps the most complete expression; from an almost allergic reaction to his Professor at Weißensee, Rudi Högner's, passionate adherence to the closed form, and against which the young Dietel rebelled, recalling that when tasked with designing a machine for a foundry "I tried not to work with closed cladding but with open components"; from the political reality, "an inner reflex on our part to the closed society DDR is to be assumed".

And from inspiration found in another creative genre: "music played a major role for me", for all jazz, specifically "the open forms of jazz " as interpreted by the likes of Stan Getz, Ella Fitzgerald or Dave Brubeck, and from which arose an interest for the likes of Bach, "his open structures, with the fugues, how he constructs the works ..."

A not irrelevant influence in the career of designer whose work can be understood as a development and extension of the positions of the inter-War Functionalist Modernists, for, as previously discussed, Bach was an important influence on those Expressionist artists who were so central to the development of Bauhaus Weimar, who in essence were Bauhaus Weimar, the likes of, for example, a Johannes Itten, a Lyonel Feininger or a Paul Klee, the latter once employing two bars of a Bach Adagio as the basis for developing a visual form.

Yet while Bach's fugues may have been the soundtrack to both Bauhaus Weimar and das offene Prinzip, the visual, formal, impulse for das offene Prinzip, as so neatly expressed in the Simson Mokick, came not from Weimar but from from inter-War protagonists of a different hue: "the alignment of bodies, the free order of shapes in space " ... "not arranged as with El Lissitzky, or Kandinsky, linearly stereometrically, but surfaces and spaces structured with flowing free bodies. Something that can be seen with Mirò, and which with Hans Arp is divine".

For all the latter being an important influence on Dietel, and again not irrelevantly so, for lest we forget, Hans Arp's free artistic understandings were also a great, defining, influence on Alvar Aalto, another designer who helped move inter-War Functionalism in much more humanistic, human, responsive, directions, another designer who helped liberate Functionalism from much of its technical dogma.

And a discourse between art and design, an understanding of the necessity of art in design, that as die offene form helps one appreciate, is central to Karl Clauss Dietel's approaches and positions.

For all that Karl Clauss Dietel's name is on the cover, and that Karl Clauss Dietel is without question the central protagonist, die offene form is in many regards not a book about Karl Clauss Dietel, as a book it is not to be confused for a Karl Clauss Dietel biography, we're not even sure it mentions his date of birth; much more it is a work that uses Karl Clauss Dietel as a conduit, a perspective, a voice via which to approach and then explore the (hi)story of design in the DDR, for all industrial design in the DDR.

If that was intended or if the project developed in that direction over the several years it's been in preparation, we no know; we do however very much approve as it bequeaths die offene form a multi-dimensionality and a vitality that it would otherwise not have.

And also allows one very direct access to the realities of design in the DDR, for all to the problems of design in the DDR, including the problems of working, as Dietel did his entire career, as a freelance designer in a socialist state, a socialist state that wasn't that keen on freelancers, was very much in favour of designers being directly employed by manufacturers/industry, but which, as die offene form discusses and dissects, rather than ban freelancers sought to make life for them difficult. A reality that made life as a freelance designer in the DDR anything but light.

And a reality which as die offene form elucidates, Karl Clauss Dietel sought to change; Dietel, as one learns through the course of die offene form, is and was a very staunch, passionate, vocal, defender of the freelancer, is and was very much the opinion that the freelancer brought and brings a value to a company over and above that of their designs, that freelancers are necessary for the meaningful development of goods of all genres in context of evolving and developing societies.

A committed defence of the freelancer which brings us back to Dieter Rams: whereas, and as noted in context of the exhibition Braun 100 at the Bröhan-Museum Berlin, in the early post-War decades the, then, Braun Design Director Fritz Eichler promoted cooperations with external designers, most notably the HfG Ulm, after Dieter Rams succeeded Eichler he set very much on in-house designers, the likes of Gerd A. Müller, Dietrich Lubs or Ludwig Littmann who were responsible for so much of the Braun output from 1970 onwards. And thus one has the fascinating position that many of those Braun objects so closely associated with post-War West Germany, were developed via a system promoted by the East German authorities and rejected by some of the leading designers in the former DDR. Yes, there are contextual differences, very, very important contextual differences we certainly aren't ignoring nor downplaying; but, in Dieter Rams' advocating the primacy of the in-house designer he stands diametrically opposed to a Karl Clauss Dietel, and very much on a line with the Amt für industrielle Formgestaltung, AIF, the official organ responsible from 1972 onwards for coordinating and controlling industrial design in the DDR, and who caused so many problems for Karl Clauss Dietel and his contemporaries. Which is, we'd argue, well worth reflecting on.

The problems of designing in the DDR were, as die offene form further elucidates, also of a much more mundane nature, something very neatly illustrated by the so called Großer Windkanal, large wind tunnel, in Dresden, a facility erected in the 1950s to assist with the development of jet engines, another oft overlooked aspect of DDR industry, and which Dietel was allowed to use to optimise the aerodynamics of his car designs: albeit on the one hand "we could only use it at night because the energy demand was comparable with a small town of 15,000 inhabitants", economic considerations and infrastructural weakness being never that far away in the DDR; nor was the government's obsession with beating, being better than, the West, and thus over time Dietel's opportunities to to use the wind tunnel were reduced, "because therein the bobsleighs were optimised - strategically more important than cars". One senses that it still rankles, one hears that his incomprehension of the authority's priorities has never subsided. But in the interests of fairness, East Germany dominated the bobsleigh at the Olympics and World Championships in the 1980s, a decade which was essentially a private contest between the DDR and Switzerland, with West Germany but a bit player. And so the bob designers and engineers of the DDR were obviously making good use of the Großer Windkanal. And the Dresden nights.

And in any case, aerodynamics were not Karl Clauss Dietel's principle problem in context of his car design work.

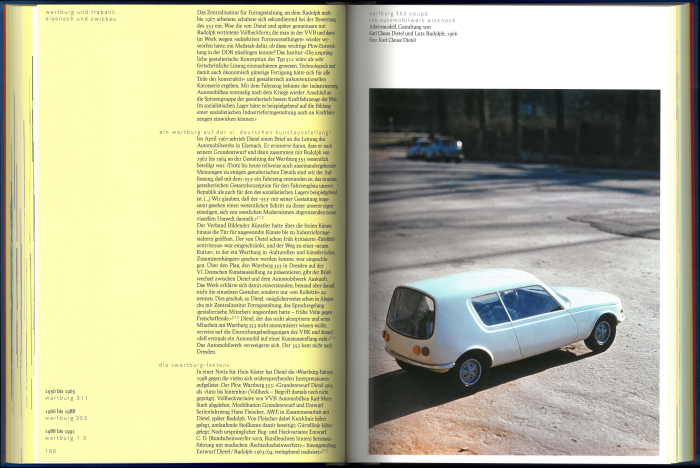

Designers, much like authors or musicians, are generally assessed, judged, understood, by those objects and projects that are realised; that which never made it from prototype to production, those drafts that were never published, tending to be overlooked. A fallacy and error that Karl Clauss Dietel's ill-fated Trabant P603 neatly illustrates.

Developed by Dietel between 1963 and 1968 as a replacement for the Trabant P601, before the East German government pulled the plug on the project and decided to maintain the P601, that Trabant we all know as the Trabant today, the defining feature of the P603 is and was that it is a full hatchback; at that time a rarely exploited concept in global car design, and one that for Dietel offered both the maximum amount of inner space in the smallest volume, and also the maximum amount of variability and flexibility for the contemporary user, a user very different from the car user of generations past, in the smallest volume, and thus was very much not only in line with das offene Prinzip but also in line with his tenet that "everything that fulfils its function with the smallest possible volume, augments humankind".

A full hatchback in service of the user which, as die offene form in its long discourse on the P603, and also on Dietel's myriad associations with Wartburg and Trabant, allows one to appreciate, embodies much of Karl Clauss Dietel's positions not just on car design but of the, at times imbalanced, relationships between cars, users and societies; and which thus as a project is every bit as instructive and informative in Dietel's canon as the Simson Mokick.

A full hatchback in service of the user which in many regards stands proxy for Dietel's many thwarted car design projects; Dietel's positions and the East German authorities' positions rarely overlapping.

And a full hatchback in service of the contemporary user which the imperialist West achieved in the early 1970s, a decade after the development of the Trabant P603, with the VW Golf.9

As we opined from the exhibition German Design 1949 - 1989 at the Vitra Design Museum, in context of the differing receptions of design from the former West and East: the Trabant is a joke, the VW Golf an ideal. But what if that Trabant was not the P601 but the P603? Olympic Bobsleigh gold medals are all well and good in underscoring your superiority to your neighbour, in confirming the pre-eminence of your political and economic system, the dominance of your society, no-one could disagree with that; but having a thoroughly new car design concept that is responsive to contemporary needs, redefines international standards and that your unloved imperialist neighbour will be forced to copy, is surely better. But, as we all know, making intelligent, long range, decisions wasn't the East Germany leadership's defining feature.

Much as designers tend to be defined by those projects that are realised, they also tend to be defined by those realised projects that are publicly discussed, and for all the detail and depth of the discussions in die offene form on Dietel's cooperations with the likes of Heliradio, Robotron or Simson, there are, for us, two important subjects which fly-by a little to quickly: Kunst am Bau/public space design and education. The former is discussed briefly in context of, for example, Dietel's contribution to the development of the internal and external spaces associated with the VEB Gießerei "Rudolf Harlaß", his considerations in the 1970s on Karl-Marx-Stadt, or his opinion that environmental, spatial, design as practised in the DDR of the late 1980s, was more advanced than much practised today. But Dietel's oeuvre is much larger than that depicted in die offene form and, we'd argue, forms a relevant part of not only his biography but his relationships with Karl-Marx-Stadt/Chemnitz/Sachsen. While in context of the latter, in the course of his career Dietel taught at Burg Giebichenstein Halle and at the Fachschule für Angewandte Kunst Schneeberg, including a tenure as Director in Schneeberg which coincided with the end of East Germany and which itself ended with the formation of the new unified Germany. Teaching which, we'd argue, is important in enabling extended understandings of Karl Clauss Dietel beyond Karl Clauss Dietel, the question of how Dietel's positions were taken on and developed, or rejected, as he rejected Högner's closed constructions, by younger generations. And teaching you'll struggle to find in die offene form. Schneeberg isn't even indexed.

Yes, it is very mean to complain about what isn't in a book or isn't in an exhibition. And unfair. Not only are their natural limitations of time and space, but the finished product must be rounded and form a coherent, cohesive whole, must be meaningful and approachable, and if it leaves you keen to do more reading and research yourself, so much the better. And die offene form is such a work, the concept is clear, is cleanly executed and stimulates one to explore further.

Is however, as the brevity afforded such themes tends to confirm, a work very much focussed on industrial design, on Karl Clauss Dietel as an industrial designer, a thus a work which for all its fulsomeness is only part of the stories: is only part of the Karl Clauss Dietel story and is the story of only part of design in East Germany. A partial telling confirmed by a much more glaring omission.

As a work die offene form closes as the DDR opens; save, for example, the reprinting of a 2001 text by Karl Clauss Dietel on the future of transportation and a few pointed comments by Walter Scheiffele, we'd argue justifiably pointed, on the post-1989 treatment of much of DDR industry, and the designers who worked with it, die offene form largely stops in November 1989.

Does that matter?

On the one hand, no.

Post-1989 meaningful large scale industrial design work largely dried up for Karl Clauss Dietel, as with so many in the former DDR the new unified Germany having no real interest in what he could offer. And for all the implicit harshness, sadness, disbelief, irrationality and unfairness, within such a statement, it is a reality. And a reality which means that only discussing the practising industrial designer Karl Clauss Dietel up until 1989 is, in many regards, how one must discuss Karl Clauss Dietel as a practising industrial designer.

On the other hand, yes.

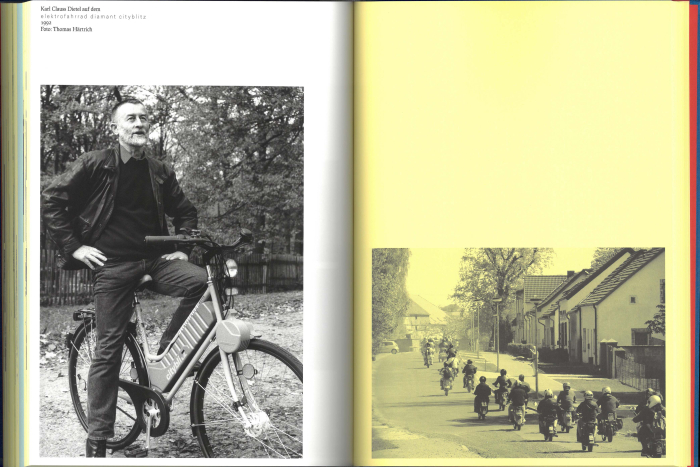

Post-1989 meaningful large scale industrial design work largely dried up for Karl Clauss Dietel, as with so many in the former DDR the new unified Germany having no real interest in what he could offer. And thus in order to properly understand, to correctly chart, the (hi)story of design in Germany it is important to document and discuss the experiences of ex-DDR designers in the 1990s, to chart their careers into the new unified Germany, regardless of how successful they were. Or better put, exactly because of how unsuccessful they were. Karl Clauss Dietel didn't stop working in November 1989, not only were there commissions, including the development of a pedelec concept for Chemnitz based bicycle manufacturer Diamant, one of the earliest commercial pedelec concepts and one of those highly instructive and informative "lost" works in Dietel's canon, but he did also attempt to make contact with and establish cooperations with firms in the west of the new unified Germany. Which came to nothing. As they came to nothing for the greater many of Dietel's ex-DDR contemporaries: Why were Karl Clauss Dietel et al unable to continue that which they had developed over three decades? Why was the new unified Germany so inhospitable, non-sustaining, for the likes of Karl Clauss Dietel? What were the companies saying to a Karl Clauss Dietel? What reasons were given for not cooperating? What economic, political, cultural, social et al forces were at work? What role did ex-East Germans and their rush west, their hurried rejection of the material culture of the DDR play? What role did foreigners and their distant, potentially biased, understandings of the relative merits of East and West Germany play? What role did ex-West German designers, design critics, design institutions, design publications, et al play? Etc, etc, etc......

While on the all too rare, and thereby particularly valuable, third hand ...... although as a book die offene form closes as the DDR opens, as a work it allows Karl Clauss Dietel to extricate himself from the realities of post-1989 eastern Germany, to dissociate himself from his physical oeuvre, and to reverberate forwards.

For all that Karl Clauss Dietel unquestionably and inarguably was a designer in the DDR, as die offene form helps one better appreciate he was, throughout his career, an international designer; although the daily realities and contexts in which he worked, and problems he faced, were very DDR specific, the theoretical basis which underscores his work, his understandings of the relationships between objects, users, materials and the wider natural and human-made environments, his positions to design, make him very much a moment in the (hi)story of global design, place him very much in context of international developments in design approaches, understandings and practices of the post-War decades.

Something that can be garnered, gleaned and appreciated not only through the numerous tales told in die offene form but also through the reproduction in die offene form of selected texts by Dietel; tales and texts which allow Dietel's voice to be heard.

And which, arguably, is the most important aspect of die offene form, for it is their voice that designers most often lose in the turmoils of history. Something perhaps most appositely exemplified by Marianne Brandt, a designer with whom Dietel became friends in the 1960s, there is a delightful photo in die offene form of the pair in conversation in 1973, and a designer whose biography shares some unhappy, unfortunate, comparisons with Dietel's: not only were both associated with Chemnitz, but whereas Brandt's career was abruptly stalled in her late 50s by the rise of the DDR, Dietel's was abruptly stalled in his late 50s by the demise of the DDR12, Brandt's by a dogmatic rejection of all things deemed western, Dietel's by a (¿dogmatic?) rejection of all things deemed eastern.

Yet for all that we have ever more objects by Marianne Brandt, and also ever more sketches and draughts by way of appreciating just what could have been, appreciating just how much she still had to contribute in the early 1950s, her voice is largely lost, only very few texts or interviews existing, or at least are popularly known, via which to hear her today. Which is tragic. In contrast, die offene form allows Dietel's voice to be heard, allows Dietel's voice to be a component of contemporary design discourses, and to remain so going forward; and the many references in die offene form to unpublished documents in the Dietel archive pleasingly hinting that there is still a lot more to be heard from Karl Clauss Dietel...

...more accurately, a lot more to be contributed by Karl Clauss Dietel, for as die offene form helps one better appreciate, the texts and works of Karl Clauss Dietel, the positions of Karl Clauss Dietel, aren't to be understood and approached as closed definitives, that would be a grotesque contradiction; rather the texts and works of Karl Clauss Dietel, the positions of Karl Clauss Dietel, are to be understood as freely debatable contributions to an ongoing discourse undertaken against the background of ever changing cultural, social, political, economic, environmental et al realities, an ongoing discourse on design, on the relevance of design, on the function of design, on the formal expressions of design, on the responsibilities of designers, on art and design, etc, etc, etc....

Or as Karl Clauss Dietel opines at the end of his Five Big Ls of good design, and which could just as easily stand as the testament of his collected texts and works, "our thoughts were also quietly put forward here, to enable a conversation about them. Hopefully some of them are powerful enough not to be carried off again by the breeze, and to allow them to advance indispensable Functionalism through position and deed".13

The conversation die offene form enables on the indispensable positions and deeds of Karl Clauss Dietel is likewise put forward quietly, but with a well-measured force that anchors the thereby engendered thoughts.

In his reminisces of the permeability of 1950s Berlin Karl Clauss Dietel notes that in addition to the positive aspects of West-Berlin, "we also got to know the darker side of the West", and that "die simple Bananengläubigkeit, die 1989 hier aufbrach, sie hatten wir nicht", "we didn't have the naive Faith of the Banana that erupted here in 1989".

Similarly die offene form is no devotional to a Bananagläubigkeit of DDR era design, and is certainly not a hagiography of Karl Clauss Dietel, rather is a pleasingly objective, reflective, critical, detached, discussion on and journey through the (hi)story of design in and from East Germany, industrial design in and from East Germany.

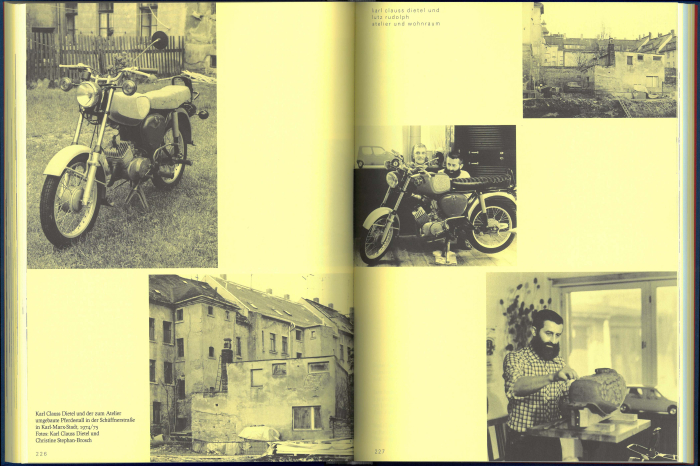

A work in which the essays and interviews are supported by sketches, draughts, archive documents and oodles and oodles of photos, including one of Karl Clauss Dietel cutting Lutz Rudolph's hair during their student days; a photo we thoroughly enjoy, not just because it allows one to understand the personal closeness of the two, nor because it makes two designers humans, which is rare, but also because they are both sat in the so-called Seminarstuhl by Selman Selmanagić, Herbert Hirche and Liv Falkenberg, one of those objects of DDR furniture design which through its ubiquity in all and any DDR design exhibition has increasingly become an object on a pedestal, and which it's really nice to see in context of what it is, a chair for everyday use.

A work in which the essays and interviews allow previously little illuminated, or known, aspects and perspectives of design in and from East Germany to become exposed, which help document the processes, systems, pressures, machinations of design, of designing, in East Germany, help document the discourses and dialogues on which design in East Germany was carried; and which means that as much as being a self-contained entity in itself it is also an important reference book, a starting point, for further research. If a larger, more extensive, bibliography would have been appreciated. Not least one with all Karl Clauss Dietel's known published texts.

A work in which the essays and interviews allow one to get closer not only to what Karl Clauss Dietel did and didn't realise, but closer to what Karl Clauss Dietel wanted, and why he wanted that; help move the focus away from the objects to the why of the objects and in doing so not only helps one better understand the designer Karl Clauss Dietel, but also helps deconstruct a lot of the unhelpful, harmful, objectification that dominates popular discussions on design in and from the DDR.

A work in which the essays and interviews through allowing one to better understand Karl Clauss Dietel in East Germany and to better understand design in East Germany, also allow one to achieve an alternative perspective on East Germany, to acquire an alternative filter through which to view and reflect on and understand and remember East Germany.

A work in which the essays exist as counterweights to the interviews with Karl Clauss Dietel, and which in moving the discussion away from Karl Clauss Dietel while keeping him very much a key component of that discussion, allows for differentiated reflections on Dietel's comments, positions and opinions, allows one to question Karl Clauss Dietel, allows one to argue with Karl Clauss Dietel, to disagree with Karl Clauss Dietel, to agree with Karl Clauss Dietel, which is important, discourse is important.

And a work which through being a documentation of and discussion on industrial design in and from East Germany via the conduit of Karl Clauss Dietel, allows one to approach the question: What if Karl Clauss Dietel's largely organic, integral, humanising Five Big Ls of good design were as popularly well known as Dieter Rams' more visual, technical, restrained Ten Principles of good design?14

karl clauss dietel. die offene form by Walter Scheiffele (Text) and Steffen Schuhmann (Design) is published by Spector Books, Leipzig, weighs in at 422 pages and features a thread-sewn cover which is haptically as engaging as the content of the book is intellectually. Full details can be found at https://spectorbooks.com/die-offene-form

And is only published in German.... and so why have we discussed it at such extreme length in English? Apart from that reason, obviously, one of the most banal reasons for the narrowness of global design understandings is language barriers - while the works designers realise tend to have a universality of language, the texts they write, and the texts written about them, tend to be only available in one language. There is no easy way round such a problem, certainly no quick way, but for our part we can discuss that which others can't read, in a language they can, and thereby try to stimulate some to improve their language skills to enable them to read a little deeper.....

1The Five Big Ls can be found in Clauss Dietel, Funktionalismus entstand und lebt nur mit Kunst, Form+Zweck, Vol.14 Nr. 6, 1982 which is reproduced in die offene form and is also accessible via https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/131357/43 (accessed 19.11.2021) And one again a big, big, Thank You!!! to SLUB Dresden)

2Langlebig sollten unsere Dinge sein ... With all five we've gone for a very free translation, we hope correctly so......

3As discussed from Simson, Diamant, Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Dietel himself uses the term Gestalter rather than Designer. And a subject given its own chapter in die offene form

4The first chapter actually opens with an interview with Erich John, followed by an interview with Karl Clauss Dietel; however, that almost all other chapters open with an interview with Karl Clauss Dietel, and that the interview with Dietel followed by an essay concept is that on which the book is based, we thought we'd keep it simple in our text for sake of readability. Apologies for the slight duplicity.

5...and all other quotes unless otherwise stated, our translation of Karl Clauss Dietel as quoted in karl clauss dietel. die offene form by Walter Scheiffele and Steffen Schuhmann, Spector Books, Leipzig, 2021

6The fact that Knoll and Braun are mentioned is in all probability no chance event, as previously noted, in 1955 a number of West German companies looking to promote new interior and lifestyle ideals began cooperating via a platform known as the Verbundkreis für Industrieform, and in which context products from one manufacturer were often displayed alongside and employed in context of works from another. Braun were an important protagonist and although Knoll were American, Knoll International was the new German based, European arm seeking to establish itself, and Knoll and Braun cooperated very closely. Why Aalto is there is a little less clear.......

7Leicht müssen unsere Dinge werden, um es nicht so schwer zu machen ... In his text Dietel plays very nicely with Leicht as both "not heavy" and "not dificult" and schwer as both "heavy" and "difficult". He also discusses leicht as "light", as in illumination

8Lütt, klein, ist jede Sache im Raum anzustreben

9There are those who see the P603 as the prototype of the VW Golf and who believe there to be a connection between the cessation of development of the P603 in 1968 and the appearance of the VW Golf in 1974..... And certainly there are formal similarities between the first generation Golf and not just the P603 but many other of Dietel's unrealised 1960s and early 1970s hatchbacks, including the Wartburg 353 coupé, and so........ However we'd also mention the Renault 16, launched in 1965, which is a full hatchback and may have inspired VW more than Dietel. In the 1960s hatchbacks were in the air, and Karl Clauss Dietel with out question a very early developer of the concept and one who'd forged his own path to the hatchback.

9Lebensfreundlich soll die zweite Natur erwachsen, die der Mensch sich erschafft

10Leise möchten die Dinge um uns sich verhalten ... Loudless isn't a word, but we needed an L.....sorry.....

11Our math doesn't quite work... Marianne Brandt was born in 1893 and thus 60/61 when she when she left the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung in 1954; Dietel, born 1934, and thus 55/56 during the process of political and economic German-German unification in 1989/90 ..... It works better if we are less specific and assume that Brandt's problems began in the late 1940s and Dietel's became more serious in the early 1990s, then both are in their late 50s. But the point is both were years away from considerations on retirement. 60 is very young for a designer.

12Leise auch wurden unser Gedanken hier vorgetragen, um das Gespräch über sie zu ermöglichen. Hoffend, einiges davon ist eindringlich genug, um nicht wiederum in den Wind gesprochen zu sein, sondern um unverzichtbaren Funktionalismus durch Haltung und Tat zu befördern

13According to Dietel the Five Big Ls were first formulated in 1975, and were first published in 1982, see footnote 1. Dieter Rams' path to his Ten Principles begins in ca. 1976 before the ten make their public debut in 1985 ... and thus there is a contemporaneous between the two. In how far the two influenced and/or informed the other we no know, but is worth asking/clarifying. A brief summary of the development of Rams' Principles can be found in Klaus Klemp, Dieter Rams: Ethics and Modern Philosophy. What Legacy Today?, docomomo 46: Designing Modern Life, 2012 Available via https://www.docomomo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/DocomomoJournal46_2012_KKlemp.pdf PDF!!!! (accessed 19.11.2021)