Braun occupy a special, ¿unique?, position not only in the mythology of product design but also in the (hi)story of West Germany; arguably no brand is as closely related with and to West Germany as Braun.

With the exhibition Braun 100 the Bröhan-Museum, Berlin, explore the development of design at Braun in the post-War decades and in doing so help one approach differentiated understandings of not only Braun and Braun design, but also of the relationships between Braun, design and West Germany.......

For all Braun's close association with post-War West Germany the (hi)story of Braun begins in pre-War Germany on June 1st 1921 with the formal establishment of the company Max Braun, Maschinen- und Apparatebau oHG in Frankfurt by..... Max Braun; an event with which Braun 100 opens. Or more accurately Braun 100 opens with a chapter titled 1921...; the ellipsis introducing the chronological flow of the exhibition's narrative, while the presentation introduces objects from the early Braun years including, and amongst others, the Manulux dynamo torch, a small pebble shaped Bakelite object which sits in the palm of your hand and which through a pumping action produces light, is, if one so will, mobile electricity in an age before we all needed, relied upon, mobile electricity; the S50 electric razor by Max Braun, a product which, according to the exhibition catalogue is as much about the patent as the product, a patent which "carried the company, technologically and financially, until the 21st century"1; or a 1928 wooden armchair by Erich Dieckmann, not for Braun but for the Städtische Zentrale für Erwerbslose in Frankfurt, a reminder of the company's origins in Frankfurt in the age of Moderne am Main. And as a chair both a pertinent reminder of how undervalued Dieckmann is today, and also one of several pieces of furniture mixed in and through the presentation which pleasingly extend the discourse away from Braun and which in doing so allow Braun to be understood in wider contexts.

From 1921... Braun 100 moves on to... 1952.

Which, yes, is a 31 year step leap.......... leap(ed) years which have a very important place in the (hi)story of Germany; and years which saw Braun remain in Frankfurt but move from Germany to West Germany where, following the death of Max Braun in 1951, his sons, the 26 year old Artur and 30 year old Erwin succeeded to the management of Braun. A succession of fundamental importance for the coming decades: Artur and Erwin's decision to update the company's portfolio, and for all to conceptually reposition the company in line with more avant-gardist understandings of the period, understandings in line with early 1950s interpretations of 1920s/30s Modernism, setting Braun on that course which is so special, ¿unique?, in the mythology of product design and in the (hi)story of West Germany.

A course on which in addition to Artur and Erwin Braun, Fritz Eichler was an important navigator.

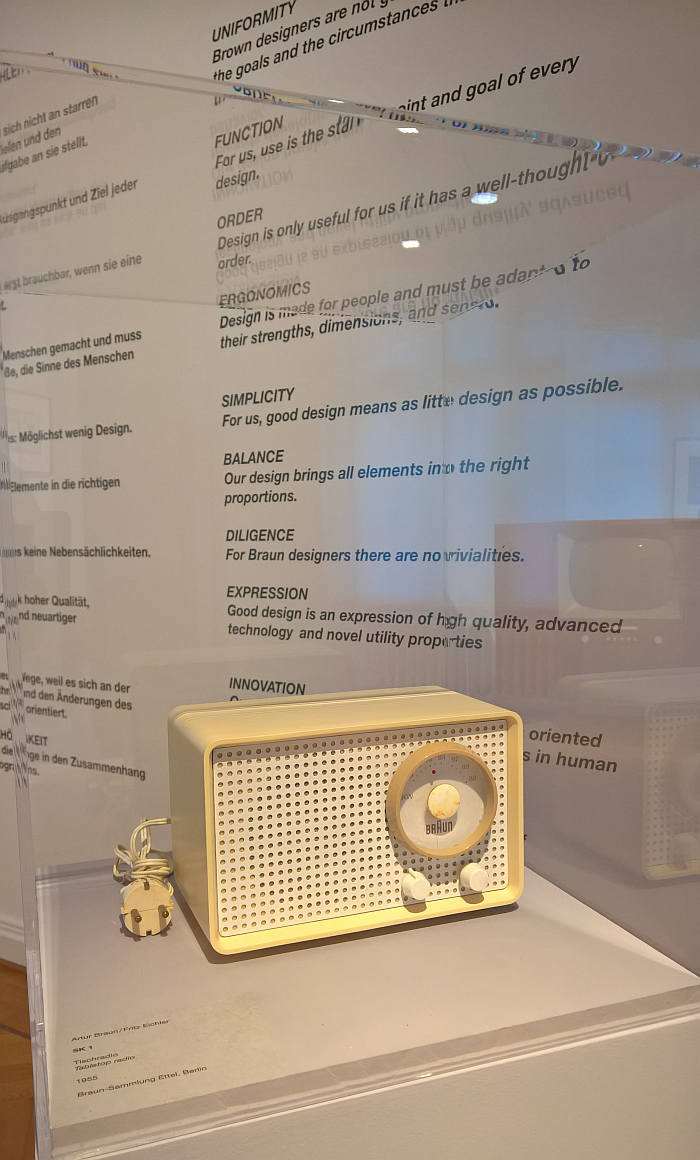

Born in Luxembourg in 1911 Fritz Eichler completed a PhD in Theatre Studies in 1936 before, and as a consequence of the 1940 German occupation of Luxembourg, serving in the German army; War service he completed alongside, and, by all accounts, in friendly camaraderie with, Erwin Braun. Post-war Eichler settled in Frankfurt, working as a freelance theatre and film director before in 1953 being brought into the Braun team where he established the in-house design studio, an institution of enormous importance to much of that on show in Braun 100, and which Eichler led until 1973. In addition Fritz Eichler was, along with Artur Braun, responsible for the SK 1 table top radio: an early expression of the new form language, of the Braun expression of post-War society, Eichler and the Braun brothers were searching for, a work that today screams BRAUN at you, but which back then, as Braun 100 elucidates, was just beginning to find its voice, was learning to articulate itself.

For all that Fritz Eichler was convinced of the importance, essentiality, of all design being in-house for the success of the venture, Erwin Braun was more inclined to cooperations with external designers, for all with designers wise in the ways of pre-War Modernism; designers like Wilhelm Wagenfeld and Herbert Hirche, whom, shortly after taking charge of Braun, Erwin contacted and commissioned. And thus two designers, two Bauhäusler, who in the early 1950s chose to settle in West Germany rather than remain in the eastern Germany they were, until then, most closely associated with. Decisions which when not exclusively, then certainly partially, made on account of the official Modernist/Bauhaus bashing of the Formalism Debate of early 1950s East Germany. Thus making Braun 100, or at least the chapter 1952 a succinct reminder of (some of) the design talent, experienced design talent, the fledgling East Germany lost on account of its own monstrous stupidity.

In addition to Wagenfeld and Hirche Braun's other key cooperation of the early 1950s was without question that with the Hochschule für Gestaltung, HfG, Ulm: an institution formed in the early 1950s; an institution, as with Braun, seeking a post-War way forward for pre-War design positions and understandings; an institution, as with Braun, seeking an expression of post-War society, an expression of the new West Germany; an institution, as with Braun, which has a special, ¿unique?, ¿mythical? place in the (hi)story of design in West Germany; and an institution who, arguably more than any other helped set Braun on its West German Kurs.

And that not just in terms of product design: Braun 100 helping one appreciate that in the person of Otl Aicher, one of the co-founders of the HfG Ulm, Braun found a creative who, along with Wolfgang Schmittel from the Braun in-house design team, was instrumental in establishing, re-modelling, the Braun corporate identity, an element of Braun every bit as important to popular understandings of Braun as the Braun product portfolio. Or perhaps better put, a corporate identity developed by Aicher in close cooperation with Braun in context of the company's design understandings, as an expression of Braun's design understandings, and which, as BRAUN became ever more confidently articulated, became ever more indistinguishable from the product design until the two became one and the same thing. And which meant/means that Braun, arguably, more so than any other company before them, became identified with and by the formal expression of their products, with and by the manner in which their products communicated with the user and the wider world. And that deliberately so. Something neatly underscored by the fact that the Braun in-house design team was officially known as the Abteilung Form- und Werbegestaltung: Department of Form and Advertising Design.

As noted in context of the exhibition Hans Gugelot. The Architecture of Design at the HfG-Archiv, Ulm, the first fruits of the cooperation between the HfG Ulm and Braun, a first public articulation of an evolving BRAUN, were presented at the 1955 Große Deutsche Rundfunk-, Fernseh- und Phono trade fair in Düsseldorf; an event at which Braun caused a furore with both their stand and their products.

The former a re-usable, modular stand concept developed by Otl Aicher and Hans G. Conrad, a re-usable, modular concept that was an absolute novum at that time, a re-usable, modular system which under the name d55 would be re-used by Braun as the basis for their exhibition stands until 1970. And which is (partially) re-used for part of the Braun 100 exhibition stands.

The latter the responsibility of Hans Gugelot and his students, and which, as noted from Ulm, aside from formal and material refinements of the existing Braun portfolio stood out for all in the manner in which Gugelot separated the existing one-piece multi-function objects into a series of separate, standardised, formally unified objects which could be freely employed alongside and/or on top one another. Were, as Fritz Eichler later commented, “light and precise-looking devices which although individuals, formed a family".2 And for all meant that just as much as with the d55 modularity had arrived in exhibition stand design, with the Braun G-11 Super radio, G-12 record player, FS-G television modularity had arrived in audio-visual technology.

Modular understandings in home entertainment systems Braun continued to develop over the coming decades, while never losing sight of the one-piece multi-function objects with which in 1930s Germany they had first entered the home entertainment market; a continuing focus indicated and announced the year after the Düsseldorf success with the release of the SK 4, a combined radio/record player, an object that is often referred to in hallowed tones, exists for many as a devotional object in the (hi)story of audio-visual design.

And an object co-designed by a young Dieter Rams. The future Mr BRAUN

Born in Wiesbaden in 1932 Dieter Rams studied architecture and interior design before joining Braun in 1955, initially as.... an architect and interior designer, but who from his earliest days was involved with product design.

Amongst Rams' earliest projects was the development of a low-cost home hi-fi system, a hole in the contemporary market Artur Braun sought to close, and which Rams approached in cooperation with Fritz Eichler. As Eichler later noted3, the pair had largely developed that which they wanted, conceptually it was ready, the individual components and lay out decided upon, but they were uncertain as to how to close the design, and for all how to enclose it. They had no casing. Nor an idea for the casing they were happy with. And so asked Hans Gugelot if he had an idea. He did.

Or rather, Hans Gugelot and Herbert Lindinger, then one of Gugelot's students in Ulm, developed the metal/wood combination case that not only so elegantly, individually yet unostentatiously houses the object; nor only which formally set the SK 4 apart from all other domestic radio-phonographic equipment at that period; nor nor only only which enables the SK 4 to make the decisive break with the long-standing understanding of radio-phonographic equipment as an item of furniture; but which also brings in a wood/metal combination that implies technology and nature, which wasn't a thing then, is now very much a thing, and is one of the myriad reasons the SK 4 has lost little in contemporaneousness since 1956.

And a wood/metal concept Dieter Rams developed further into the 1957 Atelier 1, one of his first "solo" designs for Braun, and a work in which he separated radio/record player from the speaker, a concept which although not revolutionary in 1957, was very much a concept patiently waiting for its time to come. The release in 1957 of the first stereo LP aiding and abetting the arrival of that time. And also necessitating a need for speakers the mono Atelier 1 wasn't troubled by.

Not that Braun were only hi-fi and audio-visual equipment in West Germany, they weren't. Home entertainment was however that product genre via which Braun, if one so will, announced its restart in the new West Germany, and that, as one learns in Braun 100, primarily because a survey by the Allensbach based Institut für Demoskopie suggested that many younger West Germans, and for all younger West German females, wanted domestic objects that reflected a moderne Wohnstil, a contemporary domestic environment. A moderne Wohnstil barely expressed in domestic goods in early 1950s West Germany; and notable by its absence in domestic home entertainment systems, which tended to the heavy, solid, dark wooded objects of pre-War Germany. Consequently, Artur and Erwin Braun decided to develop those competences in radio/phonographic technology and design the company had established in pre-war Germany as their stepping stone into the, still developing, moderne Wohnstil of post-War West Germany.

The chapter 1958 being the first chapter in which non-home entertainment objects appear. Or more accurately the first Artur and Erwin Braun era chapter in which non-home entertainment objects reappear; and that with kitchen machines reminiscent of Max Braun era kitchen machines presented in 1921... albeit re-formed and re-imagined in context of the changes instigated by the Braun brothers and Fritz Eichler.

And which would soon be joined by all manner of electronic consumer goods as West Germany entered the Age of BRAUN.

An Age of BRAUN dominated by Dieter Rams who in 1961 formally took charge of product design at Braun, an influence on Braun and the Braun portfolio that increased in 1973 when Fritz Eichler swapped the hustle and bustle of daily business operations for the calm of the Supervisory Board, and Rams replaced him as director of the Department of Form and Advertising Design.

For all that post-1961 Braun is and was dominated by Dieter Rams, it wasn't exclusively Rams, and Braun 100 also features works by designers such as, and amongst many others, Gerd A. Müller, Dietrich Lubs or Ludwig Littmann who all contributed significantly to the development of design at Braun, to the development of BRAUN, and who were all employed by Braun; Dieter Rams (largely) ending the cooperations with external designers.4 But before he did, Hans Gugelot, together with Fritz Eichler and Gerd A. Müller, set another milestone for Braun with the Sixtant razor, a work, as Braun 100 notes, which established the black/silver combination so identifiable as and with Braun, a product which thus deepened the interplay between corporate identity and product design, a product which, much as with Max Braun's S50 electric razor, became a foundation on which the company's future financial success would be built. And one of the last products Hans Gugelot designed before his untimely death in 1965, aged just 45. Thus making Braun 100 also part of considerations on what if Hans Gugelot hadn't sadly, tragically, died so young, how would he have influenced design in later decades West Germany? Where else would Hans Gugelot pop up in Braun 100? For he would, of that we have little doubt.

The chapter exploring Braun under the influence of Dieter Rams is, unsurprisingly given the importance of Rams to the exhibition's West German narrative, the largest chapter in Braun 100, carries the title 1968, for reasons that will become clear, and is followed by... 1995.

Which, yes, is a 27 year step leap.......... leap(ed) years which have a very important place in the (hi)story of Germany; and years which saw Braun remain in (the close vicinity of) Frankfurt but move from West Germany to Germany.

Where in the 1995 of the chapter title Dieter Rams stepped down from his tenure as Director of the Braun design department; 1995 is also the exhibition's final chapter, one which charts the post-Rams, unified Germany, era as a timeline of razors, hairdryers and irons which brings the presentation to ...2021 and thus ending its tour through a century of Braun.

A century of Braun as told by a (near) century of consumer electronic goods; and while understanding the technical nuances of the various evolutions and developments in the numerous genres does/would allow for nuanced technical understandings of what is in front of you, Braun 100 isn't an exhibition for technology nerds; not least because as an exhibition Braun 100 isn't that interested in the technology, isn't an exhibition about the evolution and development of technical specifications in consumer electronics in the second half of the twentieth century, but an exhibition about the evolution and developments in the design of consumer electronics in the second half of the twentieth century at Braun. Is about what the objects tell us about the evolution and development of design at Braun in West Germany, and also the relationships of those developments to the (hi)story of West Germany.

Considerations on the latter naturally requiring a goodly degree of generalisation and simplification, but so do all reflections on the (hi)story of design; no society, no epoch, is ever an homogenous readily definable form, we all just pretend they are because heterogeneous indiscernible masses don't fit in pigeon holes. Certainly not the finely crafted pigeon holes of cultural (hi)story. Which is always important to remember.

As noted above, a key motivation for Artur and Erwin's repositioning of Braun in 1952 was to align with post-War interpretations of pre-War Modernism, and that as a way of appealing to a younger clientele who were consuming, or at least desiring to consume, new ideals in, for example, clothing, furniture, crockery, or home entertainment equipment. The last of which being non-existent in the new West Germany.

In which context one of the more interesting objects on show is a bench by Harry Bertoia, not for Braun but for Knoll, one of Bertoia's first products for Knoll, a work released in 1952, a work that could be released tomorrow and still surprise and delight in equal measure, a work on which in Braun 100 an FS 1 television by Hans Gugelot/HfG Ulm sits. And a joyously unassuming bench that reminds that in 1955 Braun established the so-called Verbundkreis für Industrieform, a network of West German firms, as with Braun, developing contemporary products for a moderne Wohnstil, a collaborative network whose members included the likes of, and amongst others, Pfaff sewing machines, who as with Braun cooperated with the HfG Ulm/Hans Gugelot; Rasch, who in the 1930s had produced wallpaper under licence from Bauhaus Dessau; WMF, who in post-War West Germany cooperated closely with Wilhelm Wagenfeld; and Knoll5. The latter being interesting for a myriad reasons, not least because through exhibitions such as Design for Use, USA, a presentation of contemporary US furniture and household objects organised by MoMA New York which travelled Europe in 1951, or through articles in 1950s interiors magazines, post-War American design became, in the course of the 1950s, increasingly understood by many in West Germany (and Europe) as representing an ideal worth striving for, as representing an ideal of an expression of a moderne Wohnstil. As a component of the Verbundkreis cooperation all Braun exhibition stands were furnished with Knoll furniture; thus at events such as Düsseldorf 1955 or Interbau Berlin 1957 Braun's new radios, tvs and record players stood alongside, in context of and in dialogue with, contemporary US furniture by the likes of Eero Saarinen, Florence Knoll or Harry Bertoia. How could that not help Braun? How could that not help Braun establish a popular acceptance of the expression of the period and the understandings of its products it sought? And thereby allow Braun to contribute to, allow Braun to define, the rise of a moderne Wohnstil in 1950s and 1960s West Germany that was simultaneously West German and international.

Then, and as noted from Anything Goes? at the Berlinische Galerie, as the golden shine of the immediate post-War economic boom began to fade, political, social and cultural dissatisfaction began to simmer, a simmering that boiled over in 1968. And a period of political, social and cultural dissatisfaction reflected in design by the rise of not only more radical positions but also the influence of the insolence of Pop Art on design, and which for all saw the post-War interpretations of inter-War Modernism being increasingly questioned. A period of questioning and challenging of accepted conventions that also reached Braun; or as Verner Panton writes in his book Lidt om Farver/Notes on Colour, "for many years Braun confined itself to colours like white and black and, as a merry prank, grey", then in the early 1970s came....red. And as Braun 100 neatly demonstrates not just red, but yellow and green and orange and blue, I can sing a rainbow, sing a rainbow..... if a rainbow that was, as with all rainbows, transient. "Try something new!" Panton had exclaimed in context of Braun's new colourful expression, Dieter Rams, as one reads in Braun 100, didn't agree, and on his insistence the Braun portfolio quickly returned to expressing itself in "white and black and, as a merry prank, grey". Which arguably it had to given the close associations between Braun object and Braun identity, and the complexities of controlling such if you introduce diversity. Braun can't simultaneously be black/silver and a rainbow. While Braun could, and would, develop, that could only be in gradual steps within their own framework.

Developments which on the one hand enables you to understand that the Luigi Colani quote you passed coming up the staircase to Braun 100, and Colani's general tirades against the HfG Ulm, were imprecisely targeted, his target was very much Braun.

And on the other poses the question, what if in the course of the 1960s, 70s and 80s rather than adhering to their reduced, rational, ornament-free conventions derived through evolving interpretations of inter-War Modernism, Braun had questioned the basis of its existing design understandings, if Braun had embraced more of the revolution in Europe? What if, as with Olivetti in Italy, Braun had actively supported designers of more radical positions, if Braun had offered designers of more radical positions the freedom to develop those positions?

What if Braun could have tried something new?

What would that have meant for contemporary understandings of BRAUN? What would that have meant for understandings of Braun's association with West Germany? To what degree was Braun in the 1970s and 1980s informed by 1970s and 1980s West Germany? To what degree was West Germany in the 1970s and 1980s informed by 1970s and 1980s Braun?

Questions which naturally lead into reflections on 1970s and 1980s West German society: Was it as achromatic and quadratic as a Braun stereo? Was it as conclusively and studiedly ordered as a Braun coffee machine? Did a predilection for control reduce diversity? Was society brighter, livelier, more fun elsewhere in Europe in comparison to a conservative, safe, grey, West Germany? Once the dust had settled did the confusions of 1968 pass West Germany by without leaving a lasting trace? How do we remember 1970s Italy? 1970s Sweden? 1970s France? 1970s West Germany?

Don't forget the generalisation and simplification (and light rhetoric exaggeration) inherent in such questions, but they're well worth thinking about.....

And then the Wall fell.

But before it did, and as Braun 100 discusses, Braun as a company underwent a couple of interesting and important developments.

In 1967 Braun had been bought by Gillette, for all the importance of home entertainment system one should never forget the central role of razors in the Braun (hi)story, for all in Braun's financial (hi)story; and hence the chapter title 1968, the start of a new era. For all that following the takeover Braun remained very much a West Germany company, its products were increasingly marketed and sold abroad, something, arguably, reflected in the decision for colour in the early 1970s; Dieter Rams however was able to assert his belief not only in the importance of a clear, unequivocal, communication through the objects, but also in a reduced, minimal, formal expression which had little interest in t****s and fashions, which understood itself alone in context of itself, and which not only, and ironically, became a much imitated fashion, but, arguably, helped with the international marketing: Made in West Germany being an accepted quality standard, and there being little as instantly identifiably Made in West Germany as Braun.

Which, yes, does cause one to reflect deeper on the questions posed above.

Not least because, and as one reads in Braun 100, by 1983 some 75% of Braun's sales were outwith West Germany, and in 1986 some 50% of Braun's income was from products less than 3 years old; and while a more exact analysis of the numbers is necessary before making any claims, they do tend to indicate that by the time West Germany ceased to be, a goodly percentage of Braun's income was from new products sold outwith West Germany, and therefore, one presumes, new products designed for that global market rather than the West German market. The once expresser of a moderne Wohnstil in West Germany, had become an expresser of a global(ised) moderne Wohnstil.

Or put another way, not only does Braun's shift from a West German to a global brand neatly mirror how throughout the 40 years of its existence West Germany moved from being a near pariah state who had caused so much suffering and pain6 to a major international force, but is a shift, arguably, partly, aided and abetted by Braun; that through Braun's representation of West Germany, of a West Germany, Braun helped contribute to West Germany's increasing global acceptance. That having first become a formal expression of Braun, Braun products became a formal expression of West Germany.

And also, and for us absolutely fascinatingly, is the understanding, realisation, argument, therein that as West Germany neared its end Braun's association with West Germany increasingly weakened.

A weakening association poetically underscored by the fact Braun stopped producing hi-fi equipment in 1991: when West Germany ceased to be Braun ceased production of that genre of consumer goods with which the firm had re-established itself in the 1950s, with which the firm had contributed to the development of a moderne Wohnstil in youthful West Germany, with which the firm had more precisely than anywhere else expressed itself and its understandings, with which the firm had first learned to articulate BRAUN. But which was an understanding of BRAUN that was very much West German. Internationally BRAUN, certainly by the late 1980s, was clocks, hairdryers, irons, food-mixers, coffee machines et al. And the omnipresent razors. And for all was an image, a brand, an identity. And an all-pervasive mythology.

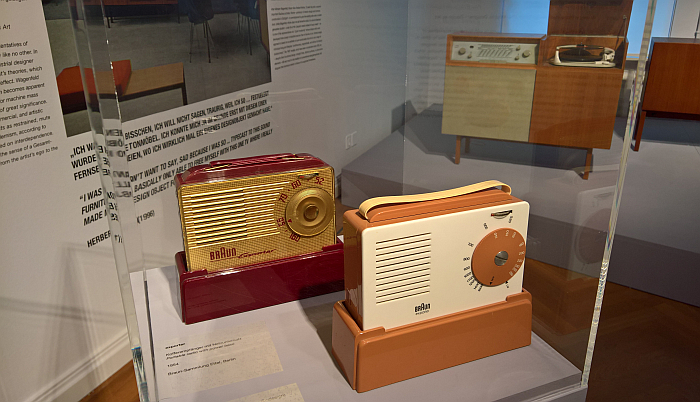

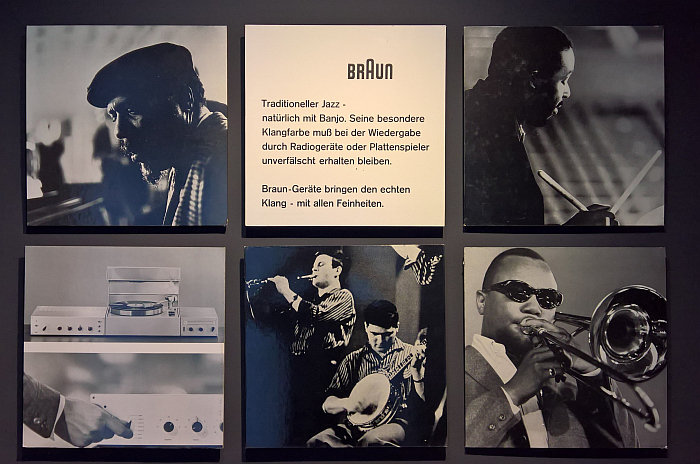

An accessible, intelligently designed and clearly comprehensible exhibition, for all that Braun 100 is an awful lot of electronic consumer goods, it never feels as if it is an awful lot of electronic consumer goods, it never gets tedious; something arguably related to the wide variety of objects presented including, and amongst other genuine delights, innumerable table/desk top cigarette lighters which seem almost prehistoric artefacts in our contemporary society; an advertising campaign, based around photos by Wolfgang Schmittel, which claims that Braun stereos are the only ones on which to listen to jazz, which, we'll continue the argument, is a particularly refined, complex and urbane music genre, like Braun stereos; or the Braun Exporter and Braun Exporter 2 portable radios, the former a ¿pre-1952? works design, the latter a 1956 HfG Ulm update which deliciously underscores both the new thinking of the 1950s and what the HfG Ulm brought to 1950s Braun, how helped it to become BRAUN. And both of whom feature a charging station that could be from next week.

A wide variety of objects ably supported and extended by succinct German/English texts on a wide variety and range of subjects; objects and texts which combine to enable subtle changes of context as you pass through the space, subtle changes in the narrative's focus which keep the presentation fresh and allow it to flow at a very natural pace, a pace you readily follow.

If we did have one complaint it would be that which is left uncommented in the leap from 1921 to 1952. In the final exhibition space visitors are invited to reflect on a number of questions on themes related to Braun, many have instead chosen to pose their own question: "1933-1945?" Which is a very valid question. We don't want to labour the point,.... well actually we do, but we're not going to...., will restrict ourselves to the comment that 1933-1945 is present in Braun 100's opening chapter in the form of a War-time ER 3 radio receiver for the Luftwaffe and a VE 301 Dyn domestic radio, the latter being an example of those, oft mentioned in these dispatches, affordable, contemporary and readily aesthetically accessible objects that so aided and abetted the NSDAP with the dissemination of their propaganda and hate. As we all know design is never neutral. Yet we all ask Alexa. And thus, for all that Braun 100 is unquestionably an exhibition about Braun in and in context of West Germany, not an exhibition celebrating Braun's centenary in its entirety, that Braun 40 would be the more apposite title, and for all that pre- and post-West Germany Germany are barely present in the exhibition, exist more as a necessary rounding of the exhibition's West German narrative rather than as a central component of it, accepting all that, you still can't, as Braun 100 does, mention the 1920s Neues Frankfurt urban planning project to which Braun wasn't a contributor, and not mention the Nazi dictatorship to which it was. And thus for us a short text on what Braun produced, and for all designed, for the NSDAP is missing. The fact that visitors have asked "1933-1945?" being more than enough impetus to study the wider story yourself once home.

Otherwise, Braun 40 100 very pleasingly allows one to approach an understanding of the development of design at Braun beyond the easier cliches, of which an awful lot can quickly arise: allows one to better understand the importance of Artur and Erwin Braun as active definers of the early course, yes, originally out of a market research analysis, but then from an honest committent to and belief in the course they had selected; allows one to better understand the importance of Fritz Eichler and the HfG Ulm to the establishment of Braun in the 1950s and how Dieter Rams, with Fritz Eichler, built on that foundation in his own manner; allows one to better understand the importance of home entertainment systems in both the rise of Braun and in Braun's own understanding of itself as it grew and became global; allows one to understand the worlds, universes, that separate Braun as it existed in West Germany and Braun as it exists today, that the two are, in many regards, and to paraphrase Fritz Eichler, although family, estranged individuals; allows one to better understand that for all the popular focus on the formal aesthetics, the graphics, of Braun products, much of the formal, structural and constructive changes and developments throughout the West German decades were functional changes and developments, technical functional, in context of how the objects work, or emotional functional, in context of how they interacted with the user or the wider environment, and not simply about producing ever new forms for the (commercial) sake of it, not about a styling that so winds up a Karl Clauss Dietel.

And in doing so Braun 100 helps helps demystify the objectification of BRAUN, helps move the collective focus to the whats, whys and wherefores of BRAUN, and thereby allowing for more probable understandings of BRAUN. And ample scope for differentiated reflections on culture and society in West Germany.

Braun 100 is scheduled to run at the Bröhan-Museum, Schlossstraße 1a, 14059 Berlin until Sunday August 29th.

And until Sunday August 29th you can also view the exhibition Luigi Colani and Art Nouveau, which offers a different take on design in West Germany, a different take on the interpretation of inter-War Functionalist Modernism in post-War West Germany, and how often is design in West Germany reflected on in a museal context? Braun 100 together with Colani and Art Nouveau being very much the sort of smaller, more, specialised exhibitions we had in mind at German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History at the Vitra Design Museum, via which to deepen understandings. Viewing Braun 100 together with Colani and Art Nouveau also posing a few very interesting what ifs? And is something we'd very much recommend you do if you get the chance.

Full details can be found at www.broehan-museum.de

For all who can't make it to Berlin, or who can and want to prepare in advance, there is also a fulsome bilingual German/English online exhibition guide available at guide.broehan-museum.de/braun100

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

1Tobias Hoffmann [Ed.], Braun 100. Design - Gestaltung - Kunst - Haltung, Wienand Verlag, Köln, 20201

2Fritz Eichler, Realisation am Beispiel: Braun AG, in Hans Wichmann, System-Design, Bahnbrecher: Hans Gugelot 1920-1965, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 1987

3see, Klaus Klemp, Ein Glückskind mit einigen Vätern. Die Radio-Phono-Kombination SK 4, in HfG-Archiv/Museum Ulm and Christiane Wachsmann, Hans Gugelot. Die Architektur des Design, avedition, Stutttgart, 2020

4A sight aside, but, as far as we could see all designers featured in Braun 100 are male, which got us thinking about electronic consumer goods in general and the gender balance in contemporary electronic consumer goods design. And which from our quick, and non-academic, survey appears to be even more male dominated than furniture design, which can't be right......

5Knoll Associates established Knoll International in Stuttgart in 1951 primarily to enable them to fulfil US government commissions in Europe, but which also enabled them, and that as the first design led US furniture manufacturer in the post-War era, to serve European domestic and contract markets. Something membership of Verbundkreis für Industrieform was, we presume, intended to promote and advance.

6As were the new East Germany, but because they were now Marxist-Leninist's their role in Fascism was easier to deny......