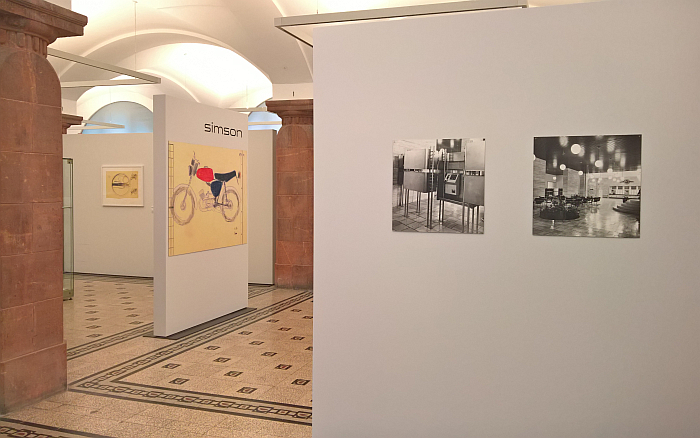

Simson, Diamant, Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

“In his work the designer seeks to find the constancy of the good”, wrote Karl Clauss Dietel in 1973, a lightly articulated yet not so straightforward task for, as he continues, not only is the assessment of such dependent on a myriad varying factors, but “the search for what defines design, what it grows from, where it comes from and where it wants to go, takes on new dimensions against the background of our cultural upheaval”.1

With the exhibition Simson, Diamant, Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz allow insights into not only how Karl Clauss Dietel understood “what defines design, what it grows from, where it comes from and where it wants to go” but how those understandings aided and abetted him in his own search for, understanding of, “the constancy of the good”…….

Born on October 10th 1934 in Reinholdshain on the edge of the sächsische Erzgebirge, the young Karl Clauss Dietel completed an apprenticeship as a Machine Fitter before enrolling in 1953 at the School for Automotive Engineering in Zwickau where he specialised in vehicle body construction, and subsequently studying Formgestaltung – Design – at the Hochschule für angewandte Kunst Berlin-Weißensee, graduating in 1961 with a Diploma project for a mid-range family car. And thus placing Dietel’s, formative, student years in exactly the period when the so-called Formalism Debate of the early East Germany with its implicit rejection by the East German authorities of the tenets of Functionalist Modernism was ebbing, and thereby allowing creatives of all hues to work freely, openly and critically in context of and informed by inter-War positions and understandings. A most fortuitous constellation for much of what would come.2

Following his graduation Karl Clauss Dietel took up a position with VEB Central Development and Construction for the Automotive Industry in, the then, Karl-Marx-Stadt, before in 1963 establishing his own design office in the city. Yes, freelance designers were a thing in East Germany, it wasn’t all VEB, LPG and Kombinate; freelance designers were however a rare thing in early 1960s East Germany, and design but a fledgling thing in early 1960s East Germany. A state of affairs neatly underscored by the fact that to satisfy the requirement of being a member of a professional association that was a prerequisite for working freelance in East Germany, Dietel was obliged to join the Association of Visual Artists, who had a sub-section Formgestalter, there being no distinct professional designer – Formgestalter – association.

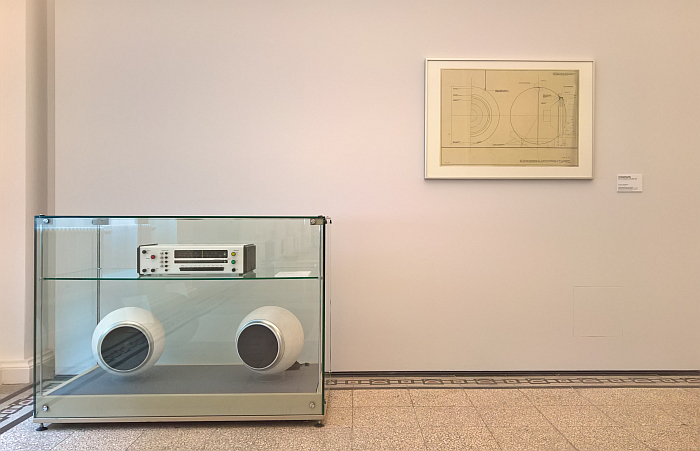

Freshly established in his own studio Karl Clauss Dietel initially (primarily) busied himself with both industrial design in the purist sense, designing machines, Capital Goods, for industry, and also with commissions from the fledgling 1960s East German computer industry, including working on the Robotron 300 an early East German midrange computer which was subsequently employed in many universities and factories, and also designing the D4a desktop computer, one of the very first, if not the first digital desktop computer worldwide, and thus making Karl Clauss Dietel one of the very first personal computer designers worldwide. Perhaps the first.

In addition, and somewhat invariably given both the path his studies and early career had taken, and also the propensity, and long history, of car making in the corner of Sachsen Dietel was raised and now lived, his early career also featured automotive design projects; one of the earliest commercial projects being the development in 1967 of the exterior and interior design of the new Wartburg 353 Limousine, a project realised in cooperation with Lutz Rudolph, at that time employed at the Zentralinstitut für Gestaltung, a continuation/reorganisation of the Institut für industrielle Gestaltung Mart Stam had established in 1950, a designer with whom Dietel had studied in Berlin, a designer with whom Dietel, as we shall see, had previously cooperated on commercial projects, and a designer with whom he would cooperate on innumerable projects over the coming decades. Including projects for the Simson of the exhibition’s title. Specifically the Simson Mokick.

A work that greets visitors to Simson, Diamant, Erika, the work with which Karl Clauss Dietel is, inarguably, most closely and popularly associated, and a work that, arguably, is best placed to explain various key facets of Karl Clauss Dietel’s design understandings and approach(es).

PRG 70000 programming unit for VEB Werkzeugmaschinenbau (top) and CNC 700 electronic controller VEB Numerik (below) by Karl Clauss Dietel, as seen at Simson Diamant Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

Karl Clauss Dietel’s cooperation, association, with Simson, or more accurately with VEB Fahrzeug- und Jagdwaffenwerk “Ernst Thälmann”3 who produced the Simson marque, dates back to his tenure at VEB Central Development and Construction for the Automotive Industry and his early freelance years, and specifically his work on the SR 4-2 and SR 4-3 motorbikes, the so-called Simson Star and Simson Sperber respectively, a commission which as Dietel notes only allowed him very limited room for self-expression, many of the components and much of the construction being pre-specified and/or taken over from existing models. Albeit a very limited room for self-expression he used very effectively, and innovatively, not least developing what he refers to as the “plastic differentiation of the components according to their function”4; which, yes, does sound like form following function. But which would be far too simple an understanding; for in addition to rational design thinking, the “plastic differentiation” was informed by emotional artistic positions, for all, as Dietel explains5, by artists such as Hans Arp or Alexander Calder and their compositions of differing plastic forms which exist in context of, and in free dialogue with, one another and with the viewer.

An interplay between the emotional and the rational of fundamental importance for Dietel: “without this lively dialectic between rationalism and emotion, that is, between science, technology and art, functionalism could not have arisen”, he opined in 1982, and that, arguably more importantly, “without this dialectic functionalism cannot continue to exist!”6 And for Dietel it had largely ceased to exist, certainly become highly endangered: Dietel arguing that the more dogmatic interpretations of Functionalism that became increasingly dominant, and also the deceitful, commercial, reduction of Functionalism down to a form – invariably quadratic and achromatic – ignored/denied this, for him, so necessary, so defining, dialectic. A position which is very much same same but different to the position Luigi Colani was advancing at around the same time in West Germany, and also very much in context of much of the international criticism of post-War Functionalism that developed in the course of the 1960s and 1970s and shaped much of what is popularly known today as Postmodernism. And a position which helps underscore that for all Dietel’s design is and was freely informed by Functionalist Modernist thinking, it was very much both an understanding of Functionalist Modernist that sought to correct some of the excess and falsehoods Dietel understood in contemporary understandings of Functionalism and which were confusing contemporary design and thereby confusing relationships between user and object, and was also an expanded understanding of “function” in product and industrial design, one that went beyond the technical, beyond a simplified form follows function understanding.

Consequently, with the 1964 Simson Star and 1966 Simson Sperber the numerous components are formed to be practically, rationally, functional, but through their relationships to both one another and to the user, also formed to be emotionally functional: an approach and understanding Dietel, together with Lutz Rudolph, refined, enhanced and sharpened in the 1975 Simson Mokick S50, and in doing so created, arguably the parade example, if one so will, the poster child, of one of Dietel’s popularly better known design positions, das offene Prinzip, the Open Principle.

Simson SR 50 (l) and MZ ETZ 150 (r) by Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph, as seen at Simson Diamant Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

As Simson, Diamant, Erika very neatly elucidates and underscores, das offene Prinzip is a recurring feature of Karl Clauss Dietel’s work, and is, as far as we can ascertain, a concept he first began to articulate in the early 1970s in conjunction with another of his key design positions, the Gebrauchspatina, the Patina of Use: Dietel arguing that whereas in centuries past objects of daily use were only replaced when they were verbraucht – used up, exhausted, worn out, finished – with the rise of objects as confirmers of status and of mass consumerism (we’ll add rise of objectification, fetishism) objects of daily use began to become replaced, as they are today, when they are gebraucht – used, not so fresh, old, not the newest model – and as a consequence the Gebrauchspatina that all objects develop acquired negative connotations, became an indicator of an urgent need to replace an object and not, as Dietel argues, and that convincingly so7, something understood as an added value in an object, arguably an added emotional value, an expression of an emotional functionality. For Dietel, in celebrating and embracing the Gebrauchspatina, via consciously and deliberately extending the lifetime of our objects of daily use, “the substance of the object, the relationship between objects and user, is preserved”, and further arguing, demanding, that “a principle of design that is open to humans and society, closed to all considerations of profit, needs to be formulated and applied”.8

With their Simson Mokick S50 Dietel and Rudolph formulated and applied just such an open principle of design.

And did so from the position that in context of complex objects, such as motorbikes, rather than a closed construction principle in which everything is hidden, inaccessible and opaque, they should be so designed so that the user can not only see how they are constructed, understand the relationships between the different components, but also designed so that the user is placed in a position, empowered, to replace and exchange components of that system over time. So with the Simson Mokick where, as Dietel and Rudolph note the tank, seat and side panels are not only “independent, plastic bodies related to each other” à la the Star and Sperber, but, and in contrast to the pre-specified closed Star and Sperber construction, they “do not conceal the supporting framework, rather are part of it and relate to the human being”9, an open construction that also enables open use: all Simson Mokick components can be exchanged and replaced, and that independent of one another and by the user.

Of equal importance is and was, as Dietel and Rudolph note that, “long production and service lifes are aimed for in context of a consistent concept”: or put another way, once bought a Simson Mokick could be used forever. The number of Simsons on the roads of eastern Germany 30+ years after East Germany ceased to be, inarguably, standing testament to the conscientiousness with which the concept was approached and realised.

In addition Dietel and Rudolph state that the concept meant that “all knowledge and demands that become apparent with time can be incorporated”. Which is what happened; over the years changes being made to several components, most notably in context of the 1981 Mokick S51, albeit always within context of the original, consistent, concept, and thus without necessitating major changes in the production nor impacting on the ability of the user to exchange and replace components as and when required/desired. The system, the principle, the Simson Mokick, remained, and remains, open.

Erika Typewriter designs by Karl Clauss Dietel, as seen at Simson Diamant Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

For all that the Simson Mokick can and does help one better approach Karl Clauss Dietel, Karl Clauss Dietel is a lot more than Simson.

He is also the Diamant and Erika of the exhibition title.

The latter a typewriter marque with whom Dietel cooperated from the start of his career in the 1960s until the end of East Germany in the 1980s, and for whom he developed numerous manual and electronic typewriters, the first of which being a study in 1965 of which Dietel notes “with this design components of the offene Prinzip were realised for the first time”, and that both formally open and also in its openness to the replacement and exchange of components. However, as Dietel notes, “for objective, emotionally determined reasons the study was rejected. It did not correspond to the perceived understanding of “typewriter” in those years”10; was, if one so will, formally and conceptually before its time. That time would come in 1976 when much of the conceptual basis of the 1965 study was incorporated into Dietel’s Erika 50/60.

The former primarily a producer of bicycles but who also produced industrial knitting machines, including, as one can see in Simson, Diamant, Erika, designs by Dietel. But who were primarily a producer of bicycles, and for whom in the early 1990s, and thus in the earliest days of considerations on and experimentation with e-bikes, Dietel developed a pedelec concept, the so-called Diamant Cityblitz. And that via, in essence, adding a new element to the existing construction, adding on battery, drive and control elements to the existing construction, which, yes, is a further example, and an extension of, das offene Prinzip; and a conversion of an existing bike to a pedelec, an acceptance of the Gebrauchspatina, a preservation of “the substance of the object, the relationship between objects and user”, popular today.

A pedelec which poses the question if an electric addition, an electric add-on component, for the Simson Mokick might not be conceivable to keep them rolling 30+ years after the last petrol station closes; and a pedelec concept which is one of only very, very, few post-1989 projects on show in Simson, Diamant, Erika.

As noted in context of German Design 1949–1989. Two Countries, One History at the Vitra Design Museum, following German unification design from the former East Germany was widely and popularly considered, derided as, secondary to the, allegedly, more valid and meaningful West German design, considerations which mirrored more general assumptions of a primacy of the (victorious) western culture over the (vanquished) eastern culture; thus while post-unification Karl Clauss Dietel sought work with West German companies and/or former East German companies under former West German control, takers he found very, very few.

Which brings us back to one of the questions we posed from German Design 1949–1989; what did post-unification German design lose from the lack of credit and respect afforded (former) East German designers? Simson, Diamant, Erika allows one to approach some answers, to approach an idea of what post-1989 Germany could have had. Not that Simson, Diamant, Erika is a place for reflecting on could have beens, although it does allow ample space for such considerations; Simson, Diamant, Erika is very much a place for approaching a better understanding of the whats, whys, wherefores of Karl Clauss Dietel.

And that far, far, beyond the Simson, Diamant and Erika of the title.

Diamant Cityblitz pedelec by Karl Clauss Dietel (prototype and commercial model), as seen at Simson Diamant Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

A title that could justifiably be extended to include Limbach-Oberfrohna based Heliradio, one of the very first company’s with whom Karl Clauss Dietel cooperated: while still students he and Lutz Rudolph began reforming and re-imagining the company’s radio and phonographic portfolio, and that very much in context of the changes Hans Gugelot and his team at the HfG Ulm were applying at that time to Braun’s radio and phonographic portfolio.11 Which isn’t an accusation, far from it, rather an observation, and one that tends to indicate that Dietel was very aware of developments in design thinking and approaches at that period; one which enables an understanding that a comparison of Gugelot and Dietel allows for interesting insights into how inter-War understandings developed post-War in the two Germanys; and one that tends to an understanding of the separation by Dietel and Rudolph of the previously one-piece Heliradio systems into individual components as the start of a path to das offene Prinzip.

While away from products, or perhaps more accurately away from commercial products, Simson, Diamant, Erika also introduces the visitor to aspects of Karl Clauss Dietel’s public space design and Kunst am Bau oeuvre, including his contribution to the 1969 Formgestaltungsprogramm Karl-Marx-Stadt, a series of public space design initiatives which had its origins in what Dietel refers to as “repeatedly discernable annoyances” about contemporary Karl-Marx-Stadt including and amongst many others, “the uniform equipment at the children’s playgrounds”, “the missing or the blinding light in the parks”, or “the benches, tables and chairs for open spaces that have to be repainted and transported every spring”.12 The latter annoyance Dietel taking on with a bench constructed from fibreglass-reinforced polyester and which although we only know from photos, and now from the model presented in Simson, Diamant, Erika, and which, as ever, is not enough to fully understand the work, is just the most joyously delicious public seating solution, a work that effortlessly and playfully combines in one answer the myriad, complex, challenges of public space furniture, a work that has lost nothing in terms of contemporaneous to this day, and a work, we’re arguing, as valid in any private garden as any public park.

Then there are the automotive projects. Throughout his career Karl Clauss Dietel continually developed automotive projects, many of which, but by no means all, were concerned with the Trabant, Dietel once referred to the Trabant P601, that enduring symbol of East German transportation, as “the worst designed mass produced car in the world”13, and which he long, actively, and ultimately unsuccessfully sought to redesign, his numerous proposals being rejected by the responsible authorities; projects which help highlight Dietel’s focus, almost obsession, in the 1960s and 1970s with developing a hatchback car, a relatively new, or perhaps more accurately evolving, concept at that period, a form, for Dietel, which “with a minimum of body size, offers a maximum of usable area”, a maximized effective space that “can be used variably, both for transporting people and luggage”14, and an internally variable hatchback envisioned by Dietel throughout the 1960s which in 1974 Volkswagen realised with the Golf. Where would Golf/Trabant comparions be today if Dietel had been allowed to develop a pre-1974 hatchback Trabant? And projects which through their inherent considerations on the fuel and material efficiency of the car more than the formal aspects help highlight the environmental thinking that underscores much, all?, of Dietel’s work. Environmental thinking inherent in das offene Prinzip, Gebrauchspatina, and also in Dietel’s Die großen fünf L, The Big Five Ls of product design: Langlebig, Leicht, Lütt, Lebensfreundlich, Leise.15 Durable, light, small, life enhancing, quiet.

Five Ls which can be understood and located in many of Dietel’s works, but perhaps most clearly in the Simson Mokick, that work which serves as such an accessible conduit to Karl Clauss Dietel. Or at least 4 of the 5 can, for today’s standards there is little quiet about a Simson Mokick, one can generally hear them coming two days in advance, but that is almost certainly solvable, certainly the Simson Mokick is designed to enable new technological standards to be introduced, conceived to enable “all knowledge and demands that become apparent with time [to] be incorporated”.

Less controversial is that Simson Mokicks are durable, small, life enhancing, and light – and more importantly lighter, Dietel and Rudolph noting that compared to other models the Mokick S50 saved 7.1 kg of rolled steel per bike16, which not only helps the fuel efficiency and thus the environmental footprint, but also helped East Germany reduce its rolled steel demand, a not unimportant consideration given the economic realities of later years East Germany. And which also reminds us that one of the jobs of any product designer is to realise new generations of products that are better than those we have, not only practically better nor only emotionally better but also productionally better, objects whose production require less resource usage than their predecessors, both direct resource usage and indirect resource usage.

Just one of many lessons a critical view of Karl Clauss Dietel’s oeuvre can allow.

Car designs and models by Karl Clauss Dietel (some in cooperation with Lutz Rudolph), as seen at Simson Diamant Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

In 2019 the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz acquired the Karl Clauss Dietel archive and began methodically indexing and cataloguing it, Simson, Diamant, Erika is the first fruit of that work and although bijou in terms of space and objects on show is expansive in terms of scope. A scope explored through a pleasingly and satisfyingly mixed and varied presentation of sketches, photographs, models and realised products, all supported by a short, take home, exhibition guide, whose texts allow the visitor to dive deeper into the oeuvre, approaches and thinking of Karl Clauss Dietel. And diving to the deeper depths is important.

Important, on the one hand, to allow us all to approach the more probable understanding of design in East Germany we need to achieve; allowing design in East Germany to free itself from both the accusations of second rateness and also from the cancerous scourge of Ostalgie under which it all to oft popularly suffers.

A more probable understanding of design in East Germany that better understanding Karl Clauss Dietel can help us all approach17; and which requires diving to the deeper depths, diving to depths which allow Karl Clauss Dietel to be understood beyond Simson, Diamant and Erika, beyond objects, and for all beyond East Germany.

To understand Karl Clauss Dietel as a designer who in his works and his writings exists very much in context of, as a valid component of, the international developments of design theory and practice since the middle of 20th century. If one little known outwith the borders of East Germany.

An understanding of Karl Clauss Dietel Simson, Diamant, Erika can help us all, start to, approach.

Or rather Simson, Diamant, Erika can allow us all to start to approach and understanding of Karl Clauss Dietel as a Gestalter who in his works and his writings exists very much in context of, as a valid component of, the international developments of design theory and practice since the middle of 20th century.

The reason we have kept the original German title of the exhibition, rather than using the English one, being that Karl Clauss Dietel refers to himself as a Gestalter, not a designer, and that not out of a dislike, out of a rejection, of a creeping anglicism of German.

Rather, for Karl Clauss Dietel the term design is both too restrictive, and also all too often popularly confused with fashion, visuals, t****s, and for all “styling”. As if to prove he is no rejector of a creeping anglicism of German Dietel has spoken out against “styling” since the 1960s, primarily in context of automotives but also in all objects of daily use; “styling” which he understands as arising where “the relationship between man and technology is out of kilter”18, if one so will the rational-emotional dialectic is out of kilter, and which for Dietel is nothing more than “a formal principle for planned obsolescence”19, about forcing consumption rather than creating meaningful, durable, responsive objects.

So Karl Clauss Dietel remains, deliberately, consciously, resolutely, a Gestalter.

And as Simson, Diamant, Erika helps one better understand, a Gestalter in all the term’s manifold glories. A Gestalter not just of forms but of relationships, of relationships between objects and users, between humans and their environment, between humans and humans; a Gestalter of systems, not a designer of products; a Gestalter who understands that all projects have, develop, a life after they have been released, and understands that while the Gestalter can’t accurately predict how that will unfold, they must be aware of it, accept that it will happen, and consider it in their work; a Gestalter who understands his place in and responsibility to society; a Gestalter whose written language is every bit as straightforward, clear, considered and engaging as his form language. And for all a Gestalter who being a Gestalter rather than a designer can help us appreciate the problems, shortcomings, with popular understandings of the term design, can help us appreciate what the term design could mean, and a Gestalter whose understandings of “what defines Gestaltung, what it grows from, where it comes from and where it wants to go” and of the importance of striving for “the constancy of the good” can inform contemporary and future design in our ongoing age of “cultural upheaval” and the ever new dimensions of the ever new challenges such presents.

Simson, Diamant, Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel is scheduled to run at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Theaterplatz 1, 09111 Chemnitz until Sunday October 3rd.20

Further information can be found at www.kunstsammlungen-chemnitz.de/simson-diamant-erika

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

Bench for Karl-Marx-Stadt and other furniture and public space designs by Karl Clauss Dietel, as seen at Simson Diamant Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

RK5 radio and K20 speakers by Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph for Heliradio, as seen at Simson Diamant Erika. Formgestaltung von Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

1. Clauss Dietel, Von den veredelnden Spuren des Nutzens oder Patina des Gebrauchs, Form+Zweck, 1973 Nr. 1. Accessible, as indeed are (near?) all East Germany era Form+Zwecks via https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/130943/1 (accessed 13.07.2021) Thank you SLUB Dresden!!

2. Perhaps also not uninteresting to note that Dietel’s student years in Berlin were the ones immedietly before the Wall was built, and thus when Berlin was still, more or less open, when passing from East to West was, relatively, unrestricted.

3. VEB Vehicle and Hunting Weapon Factory “Ernst Thälmann”, which is not only a curious mix of objects to produce, but a mix which dates back to when the factory was owned by family Simson. Before the Nazis expropriated the company from the Jewish family Simson. We’re still uncertain if the East German authorities decision to use the name Simson, more accurately to continue the use of the automotive marque Simson, was homage or derision. In East Germany the difference was often very fine and requires detailed consideration.

4. Clauss Dietel, Lutz Rudolph, Offen für Kommendes, Form+Zweck Vol. 7, Nr. 5 1975

5. Or at least does so verbally. We can’t find a written reference by Karl Clauss Dietel, but when he talks of the Mokick, two artists he regularly mentions are Arp and Calder. Whereby not uninteresting is that Arp was also an important influence on Alvar Aalto.

6. Clauss Dietel, Funktionalismus entstand und lebt nur mit Kunst, Form+Zweck, Vol.14 Nr. 6, 198

7. Clauss Dietel, Von den veredelnden Spuren des Nutzens oder Patina des Gebrauchs, Form+Zweck, 1973 Nr. 1

8. ibid Yes, one could read the words “closed to all considerations of profit” and think Yeah! East Germany! But the East German authorties loved profit, they were just rare. We understand the rejection of profit much more as being in a very similar vein to, then, Vitra CEO Rolf Fehlbaum’s criticism in context of the Citizen Office project of “commercial intention” as the “unmerciful censor of all ideas”. And there is a very strong argument to be made that that which is created for profit isn’t created for the good of society, and can only rarely be of meaningful, durable, responsive service to society. Similarly an argument that while art can be profitable, profit can never be the motivation for meaningful art.

9. Clauss Dietel, Lutz Rudolph, Offen für Kommendes, Form+Zweck Vol. 7, Nr. 5 1975

10. Clauss Dietel, Metamorphosen, Form+Zweck, Vol. 8, Nr. 1 1976

11. see Jens Kassner, Ostform – Der Gestalter Karl Clauss Dietel, edition vollbart, Leipzig, 2009

12. Clauss Dietel, Bemühen um Synthese, Form+Zweck, 1970, Nr. 1

13. Quoted in Olaf Weber, Politische Designpolitik – der Trabi, Form+Zweck, Vol. 22 Nr. 2, 1990. We can’t locate the original quote, but assume the Trabant 601 is meant.

14. Auto für die Freizeit – Freizeit für das Auto, Form+Zweck, 1971, Nr. 2

15. Clauss Dietel, Funktionalismus entstand und lebt nur mit Kunst, Form+Zweck, Vol.14 Nr. 6, 1982. Dietel notes that the five Ls were first formulated in 1975, and thus around the same time as das offene Prinzip and Gebrauchspatina were first formulated. 1982 was however their first publication.

16. Clauss Dietel, Lutz Rudolph, Offen für Kommendes, Form+Zweck Vol. 7, Nr. 5 1975

17. Clearly better understanding Lutz Rudolph is also important, however the focus of the exhibition is Karl Clauss Dietel and thus so is the focus of our text.

18. Auto für die Freizeit – Freizeit für das Auto, Form+Zweck, 1971, Nr. 2

19. Clauss Dietel, Funktionalismus entstand und lebt nur mit Kunst, Form+Zweck, Vol.14 Nr. 6, 1982 The phrase Dietel uses is “moralischen Verschleiß” which places it very much in a Marxist vocabulary, as was the norm in East Germany. “planned obsolescence” is not a fully accurate translation, but certainly implies similar.

20. Sadly Simson, Diamant, Erika closes two weeks before German Design 1949–1989 opens at the Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau, Dresden, otherwise one could have explored Dietel and Rudolph’s Simson Mokick and RK 5 and K20 for Heliradio in two different contexts. And in two sächsische meteropli that in their own ways are closely related with the career and oeuvre of Karl Clauss Dietel. Which would have been enormous fun……

Tagged with: chemnitz, DDR, East Germany, Karl Clauss Dietel, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, simson diamant erika, Simson Mokick