smow Blog Design Calendar: January 10th 1875 – Happy Birthday Louise Brigham!

“Boxing is not an exclusively athletic term in these practical and utilitarian days”, noted John Crocker in 1913, rather, “the making of useful and ornamental things for the home, from the boxes, that in other days adorned the rear of stores, is the nucleus of armament that has made “boxing” a pursuit that contains both amusement and substantial results.”1

And nobody contributed more to promoting and advancing the amusement and substantial results of the practical and utilitarian craft of domestic boxing than Louise Brigham.

A contribution that for all it may have been little recognised in recent decades remains as informative and instructive in the early 21st century as it was in the early 20th century…….

Louise Ashton Brigham was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 10th 1875 as one of five children to William and Maria Brigham, proprietors of an apothecary in nearby Medford……. and little more is known of her earliest years2, save the death of her mother when she was but two, and the death of her father when she was but 19; after which Brigham becomes visible in New York where she studied at first the Chase School of Art and subsequently the Pratt Institute. The latter established in 1887 by the oil tycoon and philanthropist Charles Pratt with the aim of increasing access to education, and where Brigham took courses in “the Domestic Art, Domestic Science and Kindergarten departments”3, before in late 1897 taking up a position with the Pratt Institute’s Neighborship Association4, an institution which had arisen as “an outgrowth of the Alumnae Association” and was comprised of “chapters representing the different departments, and each chapter carries its own special line of neighborly work. Thus the kindergarten students have established a free kindergarten at Greenpoint”.5

Specifically a free kindergarten established within the Astral Apartments housing project in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, a project initiated, again, by Charles Pratt in the mid-1880s as both housing for the workers of his Astral Oil Works and also as his response to, his solution for, the lack of affordable housing in the Brooklyn of that period; a project very much inspired and informed by contemporaneous social housing projects in Europe, for all those instigated in London by the likes of, and amongst others, George Peabody, Baroness Burdett-Coutts or Sir Sidney Waterlow6, a project which beyond affordable housing and a free kindergarten also entertained a public lunch room, a community library, offered a range of practical, domestic, skills courses and also hosted regular lectures which, judging by the announcements we’ve seen, concerned themselves with contemporary, reformist, avant-garde, aspects of society, science, culture, etc.

In addition to her work with the Neighborship Association Louise Brigham was also involved with the Brooklyn Society for Parks and Playgrounds, an association founded in 1898 as “the first society of its kind in the state of New York”7, and who in the summer of 1898 ran a free public playground a couple of blocks from the Astral Apartments; a playground that owed its existence to the “instrumentality of Miss Louise Brigham of Boston and Miss Laura Steel”8; a playground whose primary objective, according to Brigham, was, “to keep the children of the streets”, and a playground which she was keen to underscore was “conducted in a different way from the City Park playground in respect that the children are not given tasks to perform. They simply amuse themselves by passing the time in pleasant and innocent games and chorus singing”9. An understanding of a child as a child who learns about the world, and themself, through play, copying and exploration still very much in its infancy, pun intended, at that time.

And experiences with running contemporaneous, reformist orientated, playgrounds and kindergartens Louise Brigham took with her to Cleveland, Ohio.

The exact date of Louise Brigham’s move west is (currently) lost in the mists of time10, as shall be seen much of the Brigham biography is a question of conjuncture in terms of dates rather than (currently) verifiable facts, similarly the exact reason, motivation, impetus for the move west is (currently) lost in the mists of time; however, she was resident in, and therefore one presumes active within, the Hiram House settlement project for at least a year in 1900 and 190111. Dates which may give us a clue, which certainly enable conjecture. Hiram House was established in 1896 as the first settlement house project in Cleveland, and thus at a time when then settlement movement, so-called because the social workers “settled” in the locality of their work, lived amongst their clients, generally impoverished inner city communities, was very much on the ascendency in America. One of Hiram’s co-founders, George Bellamy, was additionally a leading proponent of and activist in the development of playgrounds in late 19th/early 20th century America, at that time a relatively new concept in context of childhood and child rearing: and ’twas Bellamy who oversaw the creation of a new playground at Hiram House following the institution’s move to a new location in 1899/1900. A new playground that would, presumably, require experienced, reformist orientated, staff. Thus, that Louise Brigham moved to Cleveland in context of helping establish the new Hiram House playground appears, to us, a reasonable supposition. If (currently) no more than that.12

What is more than a supposition is that in 1901 Brigham was active with the Cleveland Day Nursery and Free Kindergarten Association as a so-called “friendly visitor”, we assume a helping pair of hands, at their Louise nursery13 and also that by May 1901 she had opened her own social work, arguably street work14, project, the so-called Sunshine Cottage15, initially on Burwell Street and subsequently, and apparently on account of the necessity for a larger property demanded by its success, on Hamilton Street16; a project that as with the Brooklyn playground can be understood as a vehicle to “keep the children of the streets”, if slightly larger children, and if less in the interest of promoting innocent play as of maintaining legal innocence through avoiding association with criminal gangs; a project where, again as with the Brooklyn playground, the youths who visited were under no compulsions, were set no tasks, rather were encouraged to take responsibility themselves for using their time, a challenge they appear to have accepted17; a project which was also concerned with the wider community, for all in context of the homes of the neighbourhood, which sought through its furniture and interior design to promote and encourage the position that practical, efficient, and aesthetically pleasing furniture and furnishings weren’t a preserve of the wealthy, was something open to all, something to be recommended for all, or in the words of contemporary observers, Sunshine Cottage sought to be, “an object lesson to show people what a very attractive interior may be had with a very small outlay of money”18 and which “will afford a model for the poor people to copy”.19

And a Sunshine Cottage project which although, as we shall see, was very important in the development of Louise Brigham, was but a brief episode in the biography of Louise Brigham.

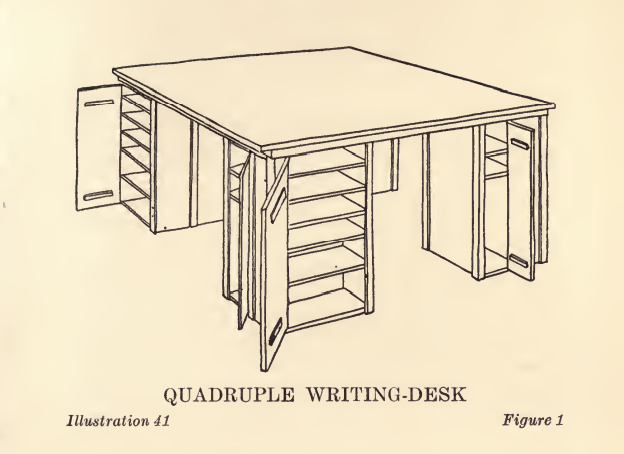

A quadruple writing-desk by Louise Brigham from Box Furniture, 1909 (the top is an extra piece of wood, the four pedestal legs crafted from packing crates) (sketch by Edward Aschermann)

Around 1904 Louise Brigham contracted typhoid, and, and whether as a direct or indirect consequence, stepped away from Sunshine Cottage20, if not away from the idea of Sunshine Cottage; a report from a lecture she presented to the New York Charity Organization Society in April 1905 noting that “Miss Brigham is going abroad for several years to study handicrafts with a view to establishing similar cottages on her return”21. A going abroad that began on June 7th 1905 when Louise Brigham “sailed for Europe”22, where she intended to “study interior decoration in Germany, Sweden, France and Italy”, “for the purpose of introducing decoration in humble homes”23. And a trip to Germany, Sweden, France and Italy which became, by her own account, a tour of some 19 European nations24, the original quartet being joined by the likes of Denmark, Scotland, Austria, and perhaps most significantly Norway, specifically Spitsbergen, where Louise Brigham spent the summers of 1906 and 1907 as a guest of the Arctic Coal Company.

Why Louise Brigham ended up in the barren wastes of Spitsbergen given that her stated intention was to study handicrafts and interior decoration, which one suspects were both only rarely encountered in the barren wastes of early 20th century Spitsbergen, is one of the many, many (currently) unclear aspects of the Louise Brigham biography. The popularly understood narrative is that in 1906 she travelled there as a guest of the Arctic Coal Company’s General Manager William Dearborn Munroe and his wife; the popular assumption being Brigham was there as a companion for Mrs. Munroe. We (currently) can’t ascertain who Mrs. Munroe is, other than the wife of William D. Munroe, nor how the three were acquainted, and thus how the offer of a summer on Spitsbergen originated25; however, unless there is a (currently) unknown compelling personal reason for Brigham being there, given the intentions of her trip, and the very tight schedule she must have had on departure, spending the summer of 1906 on Spitsbergen sounds like a wasted summer.

Yet transpired to be, arguably, the most important summer of her life.

For faced with the rudimentary, sparse, impersonal interior of the house she shared with the Munroe’s, a house, arguably, with amenities akin to those of the poorer quarters of Cleveland she had previously called home, Louise Brigham began creating furniture objects from the myriad shipping and packing crates that, literally, littered the mining camp.

And thus a material she had previously employed to furnish Sunshine Cottage: in the popular Louise Brigham narrative it is often claimed that she created all the furniture for Sunshine Cottage from packing crates and boxes, she didn’t, a contemporary report from Sunshine Cottage noting that while the dressing tables, writing desks and “prettiest window seats” were crafted from boxes, boards and barrels, and one presumes crafted by Brigham, the dining room furniture “was made to order by a carpenter”, as were, judging from the photos, the shelving, while the beds are metal. And there is at least one Windsor chair.26

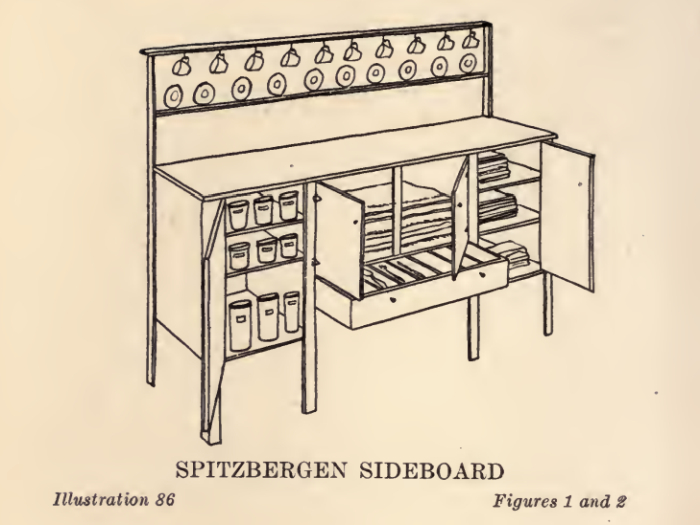

On Spitsbergen Brigham wouldn’t have had the luxury of commissioning a carpenter, or indeed a ready supply of affordable wood, and thus was forced to develop a much wider collection of objects from those packing and shipping crates she had available; and that, obviously with a great deal of passion, was obviously something which struck a chord with her, as he returned to Spitsbergen in the summer of 1907, without the Munroes27, to continue her project.28

A project which shouldn’t be confused with simply using upturned boxes as they were, Louise Brigham’s box furniture is and was no readymade project, is and was in many regards much more bricolage: Louise Brigham developing a construction system in which the boxes were “ripped apart and the material (pieces of wood and straightened out nails) put together in better form”29, and arguably also in a much sturdier, stabler form; the wood and nails were the material not the box, and the, when not standardised then arguably universal sizes of different kinds of boxes of that period, enabled the creation of a definable, systematic process, requiring but the simplest of tools and meagrest of technical skill, and which could be freely adapted to any need and any situation.

A project which following her return to New York in ca 1909 grew, and grew and assumed an existence all of its own: Louise Brigham furnishing her apartments on the city’s East 89th Street (more or less) entirely with furniture she developed and constructed from packing crates; a project which found its way in to print in Louise Brigham’s 1909 book Box Furniture. How to Make a Hundred Useful Articles for the Home30, a work that took/takes the reader step for step through the 100 articles, starting you off with very simple objects that largely used the box as it was and working up to ever more complex builds.

And a project that saw Louise Brigham return to her youth street work, and that with, arguably, more structure and a more specific direction in New York than she had left it in Cleveland.

The Spitzbergen Sideboard by Louise Brigham from Box Furniture, 1909. Requires two dynamite boxes, testimony to where it was developed….(sketch by Edward Aschermann)

Amongst her many other talents Louise Brigham was a skilled communicator, was someone who understood the necessity of networking and promotion in order to advance her projects, something one can readily understand from her earliest projects in New York and Cleveland; thus in addition to publishing Box Furniture, a work reviewed and commented on by newspapers across America, she regularly hosted journalists in her New York apartment by way of demonstrating her work and positions, regularly hosted “at homes” at which all were free to visit and interact with her work, she held regular lectures on her furniture work, published articles in magazines explaining what she had done, how she had done it and for all stressing that anyone could, and should, do it31, and participated in numerous and varied exhibitions, including the so-called Child Welfare Exhibit, an event which sought to “put matters pertaining to children before the people so strongly they will have to be seen and investigated … the kind of thing we will do will fairly startle the public into intelligent comprehension of the effects of city life upon children”32. An exhibition which after its initial run in January/February 1911 in New York moved on to Chicago, Buffalo and Rochester; an exhibition in context of which Brigham presented an installation of her furniture designs specifically for children under the title “Room Delightful”. And an installation which, by all accounts, led to her hosting a street work project for children in New York’s so-called Gracie Mansion33: today the official residence of the Mayor of New York City, then a “dilapidated and melancholy” ruin “watched over only by the park sparrows”34 and standing just a stone’s throw from Brigham’s home on East 89th Street in the city’s Yorkeville district, a district that for all its affluence today was then, as Thompson notes, “far beyond the pale of polite society”35,36. And a packing crate furniture workshop project which according to Theodore Kallman “quickly became an integral part of community life”37, and which counted some 600 boys amongst it clients.38

And thus a New York project which can be considered when not a direct continuation of Sunshine Cottage then certainly a development.

For whereas, as best we can ascertain, the youth who visited Sunshine Cottage didn’t actively build furniture, or perhaps better put, as far as we can ascertain building furniture wasn’t a regular, planned, key, activity at Sunshine Cottage, the focus being much more the demonstration of what the packing crate furniture could bring to a space, to a home39, in New York building furniture was very much the raison d’etre: the project was still very much about helping “keep the children of the streets” and encouraging them to take responsibility for their own use of their time rather than setting specific tasks, they were, for example, free to come and go as they pleased, just as at Sunshine Cottage and at the Brooklyn playground, and was also still very much about enabling poorer communities to improve their domestic arrangements with practical, cheap, furniture, the boys taking their finished objects home; however, not only the construction of the furniture, and toys and accessories, but also the organisation of the logistics for the collection of the necessary packing and shipping crates from local stores, bequeathed the Gracie Mansion project a structure that defined it and gave it a purpose beyond that of Sunshine Cottage.

And which also enables Louise Brigham’s packing crate furniture to be understood in a second context: while still very much about attempting to improve the interiors of the homes of the urban poor through practical, contemporary furniture, the shift of focus at Gracie Mansion to making rather than demonstrating, means the furniture can now be understood as much as a means to an end as the end in itself, it, arguably, had (primarily) existed as in Cleveland and Spitsbergen.

A thought which flags up the fact that until now we’ve barely mentioned the actual packing crate furniture Louise Brigham designed and built and used.

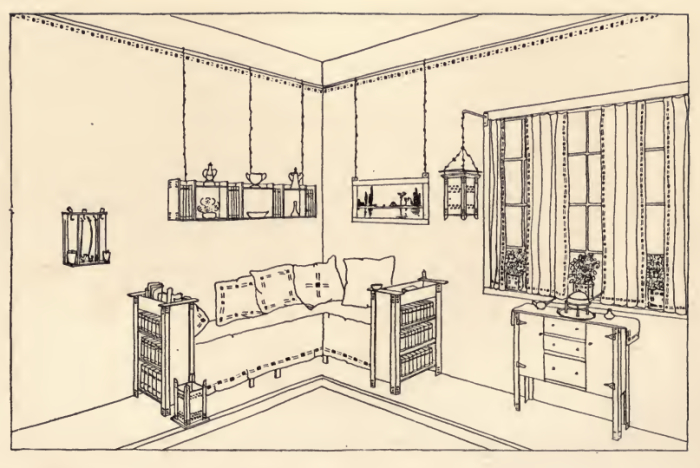

The College Boy’s Corner, as imagined by Louise Brigham in Box Furniture, 1909 (sketch by Edward Aschermann)

And which we don’t really intend to mention.40

Not because it’s not interesting and important and informative, it very much is and is and is; however, for us, Louise Brigham’ furniture is less interesting and important and informative than the hows and whys and wherefores of Louise Brigham’s furniture.

The origins of Louise Brigham’s interest, fascination, obsession, with packing crate furniture are (currently) lost in the mists of time; however, in the late 19th century such wasn’t unknown, certainly not in the USA, with numerous works, perhaps most notably and most relevantly, Emma Churchman Hewitt’s 1898 domestic advice book Queen of Home41, making several references to the creation of furniture from boxes of various genres; while, and potentially not irrelevantly, in her 1899 essay Skönheit i hemmen, Beauty in the Home, the Swedish reformist pedagogue and author Ellen Key notes of “an American authoress” who comments most positively on a “log cabin out West” where the “walls were plain logs, the tables were made of unpainted wood, the seats of packing crates”, and also notes of “a young artist couple, who could not afford to order even the simplest furniture, made all the furniture for their drawing room and dining room themselves from packing crates”.42 That unrecorded “young artist couple” may or may not have been Swedish and acquaintances of Key’s, and that unrecorded “American authoress” may or may not have been Julia McNair Wright who in her 1879 book The Complete Home notes very approvingly of an old school friend’s home in the Rocky Mountains which her, unnamed, friend, had furnished with objects created from “dry goods boxes”.43,44

Thus during Louise Brigham’s formative years, and certainly during her time in New York and the Pratt Institute’s Neighborship Association, she, arguably, must have been aware of the concept of packing crate furniture, before, and equally arguably, the need of the community in Cleveland she found herself amongst led her to her first experimentations.

And then Louise Brigham found herself on Spitsbergen in a situation of need of a similar yet different kind…….

…….whereby fully appreciating the process, the progression of steps, understanding if it is that simple, is hampered by the lack of either definitive chronological information or independently verifiable facts: as noted above, conjecture is very much one’s only true compagnon on much of the journey through Louise Brigham’s biography. (Currently)

And for us, amongst the more important and interesting questions, points of conjecture, is where was Louise Brigham between Sunshine Cottage, Cleveland, and Land-of-the-Midnight-Sunshine Cottage, Spitsbergen?

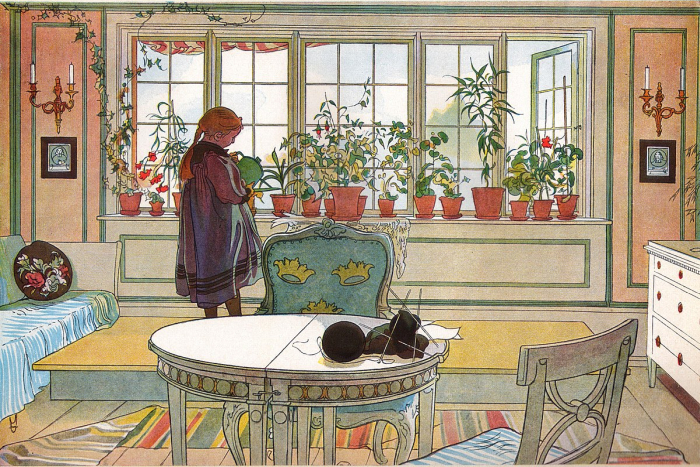

Blomsterfönstret, The Flower Window, by Carl Larsson from Ett Hem, 1899 (via commons.wikimedia.org public domain)

And for all, was she in Sweden before arriving on Spitsbergen?

In the popular Louise Brigham narrative a very, very, prominent place is traditionally given to Josef Hoffmann who Brigham met, and possibly studied under, in Vienna around…..????45 We have several fundamental problems with the prominence given to Josef Hoffmann in the popular Louise Brigham narrative, we’d don’t reject an influence of Hoffmann, far from it, but can’t buy into the primacy he is popularly afforded, too much of it makes too little sense to us; here however, sadly, is neither the time nor the place for a fulsome discussion on our objections, we’ve already dangerously distended the internet, and so they will have to wait. Here is however very much the time and the place to note, and admittedly without either evidence or knowing what potential evidence others have studied and discarded, that for us the aforementioned Ellen Key, and also Carl and Karin Larsson, were, potentially, of greater importance in the evolution and development of Brigham’s positions to and on packing crate furniture.

Again, limitations of time and space prevent us from fully expounding our argument, but do allow us to quickly note that while Ellen Key was no great fan of packing crate furniture, Key’s furniture was made by craftsfolk, she was an advocate of the ordered, uncluttered, open interiors Brigham also advocated, was an advocate of a reduction in decoration, a decoration Brigham had once sought to bring to humble homes but which is very much in the background of the formally and visually reduced objects depicted in Box Furniture, and was also, as with Brigham, an advocate of a utility in objects, of an efficiency in use of space and expediency in the cost of furnishing, believed, as did Brigham, that a meaningful, attractive, homely interior wasn’t a question of wealth but a question of reflection: Key’s assertion that beautiful interiors “can be achieved by simple means and without great expense”46, could have just have easily have been from Brigham’s pen. Barbara Miller Lane refers to Beauty in the Home as “a do-it-yourself manual for people of humble means”47, and what is Box Furniture if not a “a do-it-yourself manual for people of humble means”; the former more interior than furniture design, the latter more furniture than interior design. In addition both Key and Brigham can be considered as being primarily active in context if childcare and pedagogy, furniture and interiors being for both but a component of such.48 And thus while there are important differences in their biographies, in the nature and context of their journeys, there are a lot of similarities.49 And while we’re not implying Ellen is Key in Louise – Brigham had clearly developed a great may of her understandings and positions before setting sail for Europe50, was very much, we’ll argue, an independent thinker who forged her own way forward – we are suggesting a Key influence on the development of Brigham’s positions. And possibly vice versa. Even if Louise Brigham never appears to mention Ellen Key. Which, yes, could weaken our position.

Unless of course the pair never met. Brigham could however have been introduced to Key’s work by Carl and Karin Larsson, who she did meet. And did become friends with. And who were good friends with Key.

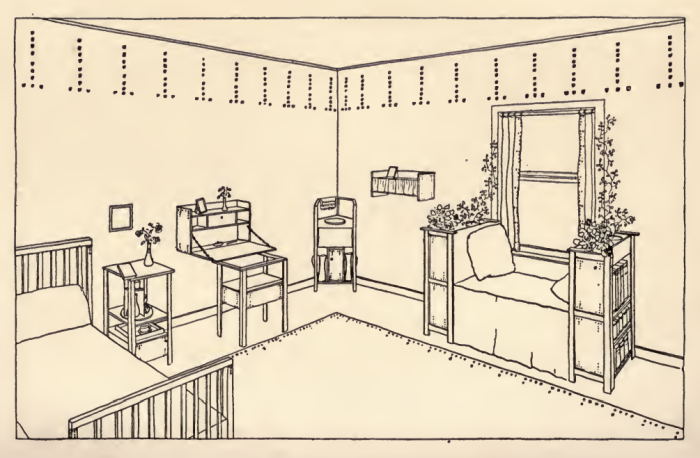

Carl and Karin Larsson were, as with Key, very much informed by the likes of William Morris and John Ruskin, whom Brigham references in the preface to Box Furniture, and the Larsson’s home, Lilla Hyttnäs, in Sundborn, became, still is, one of the paragons of the translation of English Arts and Crafts into Swedish; and while they may or may not have been the aforementioned “young artist couple” who had once furnished their apartment with packing crate furniture, they did design the greater part of the furniture, fixtures and fittings for Lilla Hyttnäs. Furniture, fixtures and fittings that although largely in a flowing neoclassical style also features more quadratic expressions of a formal, material and visual reduction, while the interior of their home as a whole expresses a simplicity and restraint, a less is more, also reflected in the room plans presented in Box Furniture.

And so, for us, there is an argument to made that having been exposed to packing crate furniture in New York, and undertaking her first experimentations in Cleveland, Louise Brigham developed differentiated understandings of packing crate furniture through her contact with Carl and Karin Larsson, and, one presumes, their like-minded acquaintances, including possibly Ellen Key, and through such began to reflect on her experimentations with packing crate furniture in new contexts, began to appreciate that packing crate furniture could be more than just a solution for those lacking resources, more than, to quote Key, “an example of how on can manage when necessary”51, and thus that context in which packing crate furniture existed in the late 19th century books of an Emma Churchman Hewitt or a Julia McNair Wright, and also in which context it had existed in Sunshine Cottage, as something for the urban poor who had no other option, and began to appreciate that packing crate furniture could be something with a value and justification of its own, as a contemporaneous approach to furniture design and construction in context of developing and evolving ideas of furniture, furnishings and interior design in the early 20th century, as a means of maintaining handicraft in the industrial age, of enabling the universal provision of high quality home furnishings against the background of ever more ever poorer quality industrial furniture. And then recognised, and grasped, the opportunity afforded by the Arctic Coal Company camp on Spitsbergen to take her considerations beyond the theoretical and test her positions under real conditions.

And thereby allow her to fully appreciate “the latent possibilities of a box”52

Assuming that is Louise Brigham was in Sweden before Spitsbergen.53

Where Sweden is without question important, is sloyd. Or more accurately educational sloyd.54

När barnen har gått och lagt sig, When the children have gone to bed, by Carl Larsson from Ett Hem, 1899 (via commons.wikimedia.org public domain)

Arising in Scandinavia in the late 19th century educational sloyd employs “handicrafts practised in schools to promote educational completeness through the interdependence of the mind and body”55, an holistic education system based on practical work rather than academic study still practised at schools in Scandinavia, and where, for example, in Finland it’s purpose is “to develop pupils’ skills with crafts so that their self-esteem grows on that basis and they derive joy and satisfaction from their work. In addition their sense of responsibility for the work and the use of material increases and they learn to appreciate the quality of the material and work, and to take a critical, evaluative stance towards their own choices and the ideas, products and services offered”.56

Amongst the most important figures in the early development of educational sloyd was the Swede Otto Salomon who, amongst other contributions, was instrumental in establishing an educational sloyd teacher training college at Nääs, in the general vicinity of Gothenburg, an educational sloyd teacher training college Louise Brigham attended during her European tour. And which may have been the reason for Sweden being placed on her itinerary: the first recorded sloyd programme in America was hosted by the North Bennet Street School, NBSS, in Brigham’s native Boston around 1889, when Brigham was, possibly, still there, with Gustaf Larsson, a Nääs graduate and director of the NBSS sloyd programme, publishing the book Sloyd in 1902, in addition educational sloyd was practised at the Baron De Hirsch Trade School in New York, the schools superintendent B. B. Hoffman publishing The Sloyd System of Woodworking in 1892.57 And thus Brigham, again arguably, would have been exposed to the principles of educational sloyd in her formative years, and given her background, interests, the manner in which Sunshine Cottage developed in its few short years, and her desire to “study handicrafts” in Europe, it is not unreasonable to suppose that her schedule on sailing for Europe included learning to teach educational sloyd.

Nor unreasonable to suppose that being instructed in the ways of educational sloyd was an important moment in her development: a supposition that takes on a tangible form in not only the Gracie Mansion street work project, which can be understood very much in context of the above quoted Finnish example, but also in Brigham’s attempts to persuade American schools to use her packing crate furniture, her furniture design approach, as the basis for practical handwork classes.58

Thus educational sloyd can, we’ll argue, be understood as that which, if one so will, facilitates the shift of focus in context of Louise Brigham’s packing crate furniture, that which enables her furniture designs to be not only an end in themselves but also a means to end, to be both a contemporary method for furnishing homes with practical, utilitarian, furniture and also as a tool in supporting the development of contemporary youth, that which meant the increased value achieved in the transformation from box to furniture was not just in context of the object but also in context of the individual. Which helps allow Louise Brigham’s box furniture to exist today as furniture, but also as more than just furniture.

And which also means that it is largely irrelevant to the Louise Brigham story that no known pieces of Brigham’s furniture survive today.

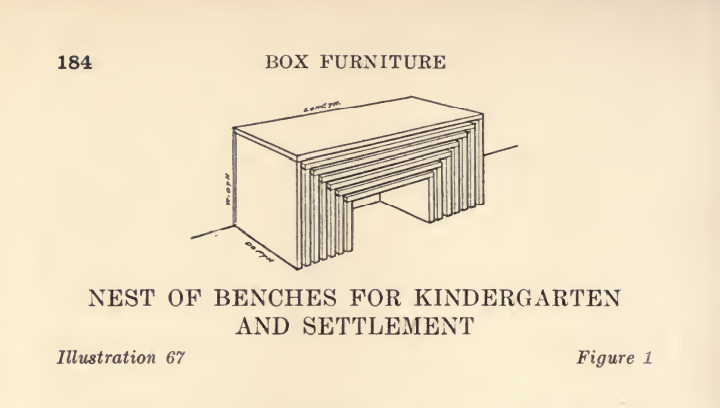

A set of nesting benches and/or tables by Louise Brigham from Box Furniture, 1909. This set was in use in her Sunshine Cottage project in Cleveland before December 1902. Which is outrageous…. (sketch by Edward Aschermann)

In order to fund and finance the Gracie Mansion project Brigham and her supporters founded the so-called Home Thrift Association, which in addition to raising funds through donations from and social functions for New York society also established the company The Home Art Masters which sold designs by Brigham, produced from virgin wood, as flat-pack mail order products, and that as, arguably, one of the very first companies globally to attempt such.59 If a short-lived venture, Kallman suggesting that restrictions on and regulation of raw material supply enforced from 1918 by the War Industries Board may have been primarily responsible for The Home Art Masters’ demise. And to which we’d add that establishing a commercial furniture company is always difficult, especially when, as Brigham was attempting with mail order flat-packs, you’re trying to introduce something very, very new.60

And in the same period in the second half of the 1910s Brigham appears to have moved away from street work and sloyd.

Why?

???

For all given the energy and time she appears to have invested in advancing her packing crate furniture projects since 1909, and the passion with which that was undertaken.

???

One popular theory is that whereas in the first decade of the 20th century packing crates were made from sturdy, quality, wood nailed together, over time they became increasingly made of “thin wood, bound together with wire bands”61 and thus thoroughly unsuitable for furniture, certainly for robust furniture intended to be used in homes over several years. And while we’ve not undertaken a history of the American packing crate, such sounds plausible against a background of increasing industrialisation. As do arguments that changing social and economic realities may have questioned the viability and function of a project such as the Gracie Mansion workshop.

In addition the second half of the 1910s saw changes in Louise Brigham’s personal life: in 1916 she married the widower Henry Arnott Chisholm, a wealthy Cleveland industrialist, and someone she had, presumably, known since Sunshine Cottage; the first Mrs. Henry Chisholm having been a supporter of the project.62 The second Mrs Henry Chisholm and her husband undertaking a year long honeymoon following their wedding and subsequently settling in Cleveland.

Married life was however short for Louise Brigham Chisholm, Henry passing in 1920, after which she moved back to New York, taking an apartment in MacDougal Alley, Greenwich Village, a street famed for its artists, that street where in the 1940s Isamu Noguchi would rent a studio and develop some of his more important and interesting works, and from where the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported Brigham Chisholm intended “to preach her doctrine of making simple, efficient furniture, and of showing others how to assemble beautiful things into a harmonic unity”63; essentially a continuation of that which she had previously undertaken, if an intention, desire, that remained unfulfilled, and which may have led her to beginning a long, and for us not particularly healthy sounding, association, fascination, fixation with the clairvoyant Edgar Cayce.64

Louise Brigham Chisholm died at the Sylvan Nursing Home in Trenton, New Jersey, on March 30th 1956, aged 81.

For all that Louise Brigham is today best known as a furniture designer, she is, was and, for us, always will be, primarily a street worker, a social worker, a pedagogue, and urgently needs to be investigated and rediscovered as such; just as much as she urgently needs to be better appreciated and understood as a designer and constructor of furniture.

For as a designer and constructor of furniture Louise Brigham is interesting and important and informative for a number of reasons.

On the one hand she was, arguably, one of the first Americans to fully immerse themselves in the developing material, aesthetic, production and functional understandings and positions of early 20th century European Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau, as in physically immerse themself not just looking at pictures and reading texts. Actually getting out there and experiencing it in the flesh. There would have been others, and Americans based in Europe, but arguably only few, if any, who would have been in a position to compare and contrast so many differing understandings, to develop appreciations of the many varying regional dialects, to contrast the handwork centred positions with the arguments of the industrialists, first hand. A circa four year craft and design study tour through Europe from 1905 to 1909 is a notable, and arguably unique, undertaking.65

On the other, while formally and materially reduced furniture which placed its focus on functionality, usability, practicality rather than representation or tradition and which had a hang to the quadratic, and was clearly inspired by European Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau, was known in America of the early 20th century, including in designs by the likes of Frank Lloyd Wright, and in objects by manufacturers such as, for example, Stickley Brothers, the Michigan Chair Company, or, and perhaps most relevantly in context of Brigham’s designs, the Charles P. Limbert Company66, it was, arguably, nowhere as elegantly expressed, or expressed in such a filigree and open and honest manner as in Box Furniture, an expression which, yes, was invariably influenced by the material employed, but which nonetheless neatly anticipates much of what would arise in coming decades, including the so-called Modern Efficiency Desk that arose in 1910s America and ushered in the modern office. Whereby, Brigham’s response to all that she was exposed to, both in Europe and America, and all the positions on and to the formal, functional and material questions of furniture she developed from that exposure and her own experiences, wasn’t to produce furniture, but to develop designs which allowed others to produce furniture as she understood furniture should be. She didn’t give early 20th century Americans fish, she taught them to fish. Or at least tried.

And on the rare, and thus highly significant third hand, there is the fact that she employed waste material, technically packaging waste, and used it not to create new commercial objects, didn’t produce objects to add to the consumer cycle, but reused it for social and educational purposes. And that, one appreciates from a study of Brigham, very much consciously and deliberately. Wooden packaging waste was as ubiquitous in the early 20th century as plastic packaging waste is in the early 21st, and wooden waste that, as with our plastic waste, was primarily burned. Brigham was one of the first people to question the sense of burning that wood waste, was one of the first to consider it as resource that could be used in a new context, and which caused the New York Times to opine in 1909 that Box Furniture “may also be taken as one of the few indications of the birth in this country of a tendency towards less wastefulness of raw material”.67,68

Was it?

Or more generally, how can one asses Box Furniture and Louise Brigham’s furniture design work some 100+ years later?

A proposal for a so-called Invalid’s Room, but could be any spare bedroom. Note in particular the wall-mounted, closable, desk and the bookcases in the window bench. The bed is not made from boxes….As imagined by Louise Brigham in Box Furniture, 1909 (sketch by Edward Aschermann)

The Austrian philosopher Paul Feyerabend argues that, “the inventor of a new world view (and the philosopher of science who tries to understand his procedure) must be able to talk nonsense until the amount of nonsense created by him and his friends is big enough to give sense to all its parts.”69

Louise Brigham’s furniture design work, we’d argue, can be considered early 20th century furniture design nonsense, which we don’t mean as an insult. Far from it.

With the benefit of a 100+ years hindsight we can all appreciate Louise Brigham much better, understand her experimentations and positions as a part of something that couldn’t necessarily be understood in its day; and also better understand the tragedy that through her fall into anonymity in the 1930s and 1940s Brigham never got to know the great many friends who helped contribute to turning that mass of nonsense she helped compile into a widely understood sense. Or perhaps better put, Brigham’s fall into anonymity makes it very difficult to describe her as a pioneer, as an early protagonist, yes, as an early practitioner, yes, but not as a pioneer, for the great many moments that should have featured her, that she should have informed and influenced and defined, arose and developed without her, without the new practitioners being aware of the old work they were building on. Something we’d argue is particularly true of the radical, counter culture, design movements of the 1960s and 1970s and 1980s.

For Louise Brigham was counter culture.

And Louise Brigham was radical.

Through developing her own construction system and employing the box as a raw material rather than as a box, Louise Brigham in effect, turned something that had previously been a low-quality response to need into a valid craft, something one could learn and then apply to your own projects, and develop according to local conditions within a universal system. And that with a waste material. Which is radical, involves a shift in perspective, a new understanding of relationships, a suspending of accepted conventions, a repositioning of values.

In which context, amongst the many comparisons of Brigham’s work with the work of later practitioners one of the most common, and most visually obvious, is Enzo Mari’s 1974 Autoprogettazione project. A comparison that beyond the visual similarities both works and doesn’t work.

Doesn’t work in that Brigham and Mari, at least initially, approached their projects from different perspectives: Mari wanting to educate people as to what good furniture is, Brigham that all can furnish their home with good, attractive furniture. And which as such brings Box Furniture much closer to Thomas Chippendale’s 1754 The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker Director, both being as they were instruction manuals for the creation of contemporary furniture which everyone was free to re-produce; both being Open Design before Open Design was a thing; Chippendale’s carrying the subtitle A large collection of the most elegant and useful designs of household furniture which echoes 150+ years later in Brigham’s, How to make a hundred useful articles for the home: the major difference being that while Chippendale’s was aimed at Noblemen, Gentlemen and their wealthy ilk, Brigham’s was for everyone regardless of wealth and status, is an equitable, universal, inclusive Director. Which, we’ll argue, is glorious and something to be applauded.70

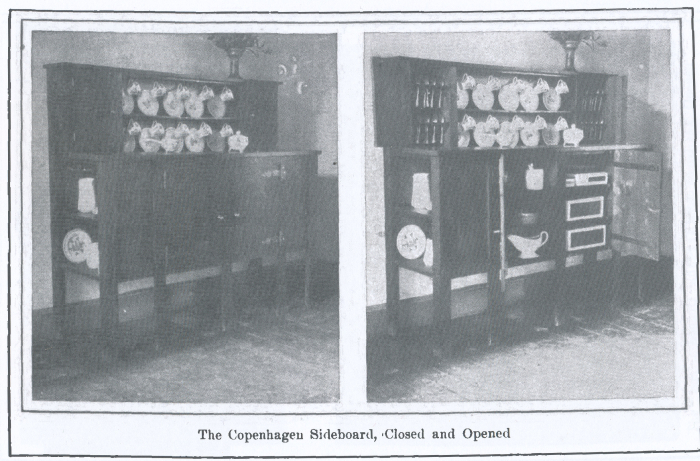

Does work in context of Mari’s opinion that “the real need for a manufactured object correspond[s] to the moment of its production”71, that an object only meaningfully exists in a definitive reason for its creation, at the moment that need is satisfied and in the people who create it, not in its being, that any object is why it is not its what it is; which is also what Louise Brigham teaches us not only in her use of packing crate furniture as a method of improving domestic comfort in the poorer areas of Cleveland, nor only in her using it to relieve the privations of a Spitsbergen mining camp, nor only as a social and educational tool in the Gracie Mansion workshops, but also, for example, and amongst other projects72, in the furniture she developed for a settlement project in Copenhagen in context of a workshop in autumn 1907, and also in the, sadly, only very limited 1918 project that employed emergency aid crates as the basis for furniture for war ravished villages in France73, a project which, we’ll argue, is approaching genius as a nose-to-tail approach to emergency aid provision. And one which has lost nothing in its contemporaneous and from which there is much to be learned.

We don’t believe for minute Louise Brigham understood her work in that context, we’re not even sure that would have been possible in 1909; but she did understand her furniture designs as being about more than just objects of furniture, something Louise Brigham was able to do because she wasn’t a furniture designer, she was a street worker and pedagogue who reflected on and employed furniture design in her work. Which was, arguably, part of her problem; for (near) everyone else in early 20th century America furniture was furniture, and there was no framework in which to understand furniture as anything but furniture, any other understanding was nonsense, and so the social and environmental and economic and value aspects were (largely) ignored.

As subsequently was Louise Brigham.

Louise Brigham’s popular rediscovery (largely) begins with a 1996 essay by Neville Thompson74 and has reached its contemporary highpoint with Antoinette LaFarge’s 2019 book Louise Brigham and the Early History of Sustainable Furniture Design75, a work that allows for a sprightly if satisfyingly wide and varied tour through the life, times and works of Louise Brigham, a tour in a number of contexts, a tour that casts light on a great many previously lost subjects; and a tour which also underscores just how much is still unknown, how many questions are still (currently) unanswered, how many questions are still (currently) unposeable.

Questions that need to be posed and answered not only to allow us to better understand Louise Brigham and to allow her fully reclaim her place in the (hi)story of furniture design, her place on furniture design’s helix; nor only to allow Louise Brigham to become the pioneer she should always have been, the contexts of Louise Brigham’s work and the reflections those engender on our relationships with our objects of daily use, allow Brigham, we suspect, to be as relevant in the future as she should have been in the past; but also in helping us all better appreciate that throughout the ages and years of human society, for youths seeking to find their place in the world, seeking to find a path through life, a path to themself, boxing has always been capable of engendering more amusement and more substantial results than boxing.

For all when one has a boxing trainer who understands their craft.

Happy Birthday Louise Brigham!!

1. John Crocker, A Visit to “Box Corner”, National Magazine Vol 37, Nr. 4, January 1913, 775-779

2. The Cleveland Plain Dealer notes that as a girl she “had her schooling in Europe”, which may be true or may be a misinterpretation of her European tour in her 30s (Eleanor Clarage, Main Street Meditations, The Cleveland Plain Dealer, Monday February 4th 1929, page 20); Crocker (see FN 1) notes that “Miss Brigham’s first work was begun in connection with sand gardens and home libraries in Boston”, the Sand Gardens being a playground, or more specifically “a mound of sand was donated by Waldo Brothers and was placed at the Parmenter Street Chapel in Boston’s North End” (Kyle James Fritch, “The Right to Play” The Establishment of Playgrounds in the American City, MA Thesis, University of Massachusetts, August 2018), a playground/mound of sand, which opened in Boston in 1885 as one of the first public play spaces for children in the city and which as a concept appears to have spread USA wide in the late 19th century. Similarly the New-York Daily Tribune notes that “for years [Brigham’s] work was aiding in the development of the home library movement [in Boston]”. (This Woman Wields a Hammer, New-York Daily Tribune, Sunday May 15th 1910, page 4). And if true, the sand gardens and home libraries of late 19th century Boston may help elucidate who the “Cynthia P. Lane” of Box Furniture’s dedication is….

3. see Antoinette LaFarge, Louise Brigham and the Early History of Sustainable Furniture Design, Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2019 page 20

4. The Brooklyn Times, Saturday October 2nd 1897 page 10 notes that Miss Ovington, the resident worker “will be assisted this winter by Miss Louise Brigham of Boston, a former student at the institute”, unclear exactly when Brigham started.

5. Pratt Institute Happenings, The New-York Times, Monday December 17th 1894, page 12

6. see G.F.A., Problem of City Living. Difficulty in Solving it Satisfactorily, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sunday December 5th 1886, page 15

7. https://www.nycgovparks.org/about/history/playgrounds (accessed 10.01.2022)

8. Where Children Play, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Monday August 29th 1898, page 11

9. ibid Brigham also states her hope that in the long-term the park may become a year round play space akin to the Charlesbank Park in Boston, which had opened in 1895, and a reference that tends to further underscore that before New York she was involved with playgrounds and parks in Boston, see FN 2.

10. Brigham is named in March 1899 as being an assistant worker at the Astral Apartments (Brooklyn Life, Saturday March 18th 1899 page 25) and in May 1900 in context of a society wedding in New York as being of Cleveland (Patteson-Lowell Nuptials, The Brooklyn Daily Tuesday May 1st 1900, page 5), so some time between those two dates…….

11. see, Eleventh Annual Report of Hiram House, May 1st 1907, page 29

12. The answer may be found in the Annual Reports of Hiram House from 1900 and/or 1901 and/or in the editions of the Hiram House Life from around those times, but we currently have no access to them. They may also help explain if there was any connection between Hiram House and Sunshine Cottage. Yes, we assume others have already looked, apologies in advance…..

13. Women’s Activities, Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 19th 1901 page 23

14. The Brotherhood of St. Andrew apparently helped out at both Hiram House and Sunshine Cottage, in context of the latter undertaking “largely “street boy” work”, St. Andrew’s Cross Vol. 17 Nr. 6 March 1903, page 185

15. The implication is always very much that Brigham established Sunshine Cottage as an independent, individual venture; however, at around the same time the so-called International Sunshine Society, an association largely concerned with assisting the blind but which also sought “to incite its members to the performance of kind and helpful deeds, and thus bring the sunshine of happiness into the greatest possible number of hearts and homes” (From the society’s constitution and by-laws, quoted in Frederic J. Haskin, The International Sunshine Society, Los Angeles Herald, Friday Morning, May 21st 1909 page 4) was very much in the ascendency across America, and according to a 1903 article in the Buffalo Evening Times Brigham’s Sunshine Cottage was part of the International Sunshine Society movement. But that is the only reference of an association we can find, and so they may very well have been mistaken, see Sunshine Cottage, The Buffalo Evening Times, Monday December 7th 1903, page 3

16. As far as we can ascertain there is no Hamilton Street or Burwell Street in the contemporary Cleveland, if the streets have changed name or been built over we no know. What is very telling however is that the contemporary reports refer to Sunshine Cottage as being in the “foreign” districts/quarters of the city…… so presumably those not inhabited by the Shawnee, Lenape, Myaamia and other native Ohioan peoples……

17. see Mary A Dickerson, Sunshine Cottage, Ideal Home, Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 30th 1902, page 52 We assume there were also problems and that all wasn’t always as harmonious as it appears.

18. ibid We’re taking it as a paraphrasing of a direct quote from Brigham

19. Women’s Activities, Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 19th 1901 page 23 The phrasing clearly reflects contemporary attitudes. An 1894 article refers to the Pratt Neighborship Association as working “among the backward social classes” (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Monday February 5th 1894 page 6) Unsure if Brigham would have used such phrases, but would be very surprised if she had…….

20. Although Brigham appears to have run Sunshine Cottage alone she was assisted by two individuals who are variably referred to as “a deserted scrub woman and her child” (Making Box Furniture: Its Practical and Ethical Value, The Craftsman, Vol. 21 Nr. 2 November 1911 218-221), as “a woman of their own station and a little girl”, for “their” read Sunshine Cottage’s neighbours and for “own station” one can read poor immigrant, (Elizabeth McCracken, The Women of America, Macmillan, 1904 page 244 (McCracken doesn’t specifically name Brigham but the New York Times, April 3rd 1909 says it is her, and a great many of the facts line up)), and, thankfully, as “Mrs. Kronheimer and her little daughter, Vinnie” (Mary A Dickerson, Sunshine Cottage, Ideal Home, Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 30th 1902, page 52). What happened to Sunshine Cottage, Mrs. Kronheimer and Vinnie after 1904 is (currently) unclear…. [In the Cleveland Plain Dealer from Dec 25th 1902 we learn “Mrs. S. Kronheimer”, and in “Sunshine Cottage, Ideal Home” that she had the authority to fine boys for swearing, and so presumably was more than just a domestic help]

21. Notes of the Week, Charities. A review of local and general philanthropy, Vol. 14, No. 5 April 29th 1905, page 692

22. (Currently) unable to verify on which ship she sailed or where her first port of call was, which would be helpful in piecing together her trip. Reading the New York Times from early June 1905 the only two scheduled sailings we can find for June 7th 1905 were the White Star Line’s Oceanic from New York to Liverpool via Queenstown (the contemporary Cobh) and the Holland-America Lines’ Statendam from New York to Rotterdam via Boulogne. We’re assuming she sailed from New York….. And that the date June 7th 1905 is correct…….

23. American Art News, Vol. 3, Nr. 80, June 15th 1905 page 3

24. Teaching boys to make good furniture out of boxes, New York Times, January 19th 1913 We are (currently) unsure if there is any confirmation of exactly where Louise Brigham travelled, certainly no-one mentions any cast-iron documentation, all there seems to be is Brigham’s own statements, which we don’t doubt, but which one should verify, for 19 countries in ca. four years, with two summers on Spitsbergen, is a sporting schedule, for all given the European transport network of the first decade of the 20th century….

25. The Brigham family tree contains numerous Munroes, we (currently) can’t locate a William Dearborn Munroe, but that may be flaw in our research and William may have been a relative, alternatively Mrs. Munroe could have been an old friend, or Brigham might just have met the Munroes on her travels….

26. Mary A Dickerson, Sunshine Cottage, Ideal Home, Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 30th 1902, page 52

27. William Dearborn Munroe died on February 21st 1907 when the SS Berlin sank at Hoek van Holland. Mrs Munroe remained however involved with the Arctic Coal Company, at least for a while, and in 1907 worked at their office in Trondheim and helped secure Brigham’s return to Spitsbergen, see Nathan Haskell Dole, America in Spitsbergen. The Romance of an Arctic Coal-Mine, volumes I & II, Marshal Jones Company, Boston, 1922

28.s ibid Volume I, page 284, which also appears to claim that the idea for the book arose before her return in 1907 and was to be published by Scribner’s, New York. Dole also notes that Brigham took “potted ivies and other plants to adorn the engineer’s house” (page 300) and makes note the one evening in July 1907 “Miss Brigham varied her activities in furniture making by preparing eider drakes’ breasts for use as furs” (page 336), thus underscoring her technical skills went beyond carpentry.

29. Making Box Furniture: Its Practical and Ethical Value, The Craftsman, Vol. 21 Nr. 2 November 1911 218-221

30. Louise Brigham, Box Furniture. How to Make a Hundred Useful Articles for the Home, The Century Co, New York, 1909 Available at https://archive.org/search.php?query=%22box%20furniture%22%20Brigham (accessed 10.01.2022) and also in print as a re-edition through Self Reliance Books, ISBN 978-1718989078

31. Primarily in a quartet of articles under the title How I Furnished My Entire Flat From Boxes published between September and December 1910 in the Ladies Home Journal

32. Ray Smith Wallace “secretary of the committee”, quoted in Child Welfare Exhibit Planned, Trenton Evening Times, Tuesday July 20th 1909, page 10

33. We don’t know how the use of Gracie Mansion came about, but from what we do know about Brigham we suspect there was some active lobbying on her part……

34. Boxes and Boys, New-York Tribune, September 24th 1911

35. Neville Thompson, Louise Brigham: Developer of Box Furniture, in Bert Denker [Ed.] The Substance of Style. Perspectives on the American Arts and Crafts Movement, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Delaware, 1996, 199 – 211

36. The Los Angeles Times noted in 1916 that Brigham maintained an apartment on 5th Avenue where “she had a charming nursery for the children of her friends and their nurses and governesses” (Money and Art Happily Mated, Los Angeles Times, August 22nd 1916 page 16) It is unclear if she owned the 5th Avenue apartment parallel to East 89th Street or if the move came later. What is, relatively, clear is that Louise Brigham was a woman of independent wealth, presumably a sum of money inherited from her father that allowed her a very comfortable existence, in which context we’re always tickled by an ad she placed in the Cleveland Leader in 1902 for the return of a “mink collar with tails” she had lost in the city. Not sure how many of her Sunshine Cottage clients had mink collars. Or warm winter coats. (Lost and Found, Cleveland Leader March 13th 1902 page 8)

37. Theodore P. Kallman, The Pilgrimage of Ralph Albertson (1866-1951): Modern American Liberalism and the Pursuit of Happiness, PhD Thesis, Georgia State University, 1997,page 385

38. It apparently was only boys who made furniture, girls doing more “feminine” things. You’d have to ask Louise Brigham why she didn’t empower the girls more…

39. None of the contemporary reports we’ve seen make major mention of furniture making, which they presumably would have done had it been at the core of the concept at Sunshine Cottage. Or even practised by the boys at Sunshine Cottage.

40. We will come back to it at a later date, for now the pictures will have to suffice.

41. Emma Churchman Hewitt, Queen of Home. her reign from infancy to age,, from attic to cellar, Miller-Megee Company, Philadelphia, 1889

42. Ellen Key, Beauty in the Home, translated by Anne-Charlotte Harvey, in Lucy Creagh, Helen Kåberg & Barbara Miller Lane [Eds.] Modern Swedish Design. Three founding texts, Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, 2008 page 40-41

43. Julia McNair Wright, The complete home: An encyclopædia of domestic life and affairs, J.C. McCurdy & Co., Philadelphia, 1879, 157-158

44. In context of Beauty in the Home in Modern Swedish Design. Three founding texts (see FN 42) the editors note they were unable to identify the “American authoress”, we don’t know if McNair Wright was considered and rejected, but for us there appears to be enough similarities to justify the supposition that it was McNair Wright, and the dates fit……

45. The Kansas City Times heavily implies that having left Spitsbergen Brigham visited first Copenhagen and that “from Copenhagen Miss Brigham went to Vienna”, (Box furniture as an art, The Kansas City Times, Saturday September 4th 1909, page 10) and in Box Furniture she notes she was in Copenhagen in the “fall of 1907” (page 282), so presumably, if the above is true, and nothing else came in between, Brigham was in Vienna autumn/winter 1907/08. After Spitsbergen. And thus, potentially, around the time Lilly Reich was, possibly, studying with Hoffmann in Vienna. If she was or wasn’t is still unresolved. And also around the time the, then, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris was in Vienna and spending most of his time hating the city but gaily swinging along to the works of Wagner and Bizet in the Vienna Opera House. Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris met Hoffmann in March 1908, just before his departure for Paris (see H. Allen Brooks, Le Corbusier’s Formative Years. Charles Edouard Jeanneret at La Chaux-de-Fonds, The University of Chicago Press, 1997)

46. Ellen Key, Beauty in the Home, translated by Anne-Charlotte Harvey, in Lucy Creagh, Helen Kåberg & Barbara Miller Lane [Eds.] Modern Swedish Design. Three founding texts, Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, 2008 page 36

47. Barbara Miller Lane, An Introduction to Ellen Key’s “Beauty in the Home”, in Lucy Creagh, Helen Kåberg & Barbara Miller Lane [Eds.] Modern Swedish Design. Three founding texts, Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, 2008, page 25

48. Certainly for Brigham, arguably less so, or less directly so, for Key, for Key furniture and interiors were more about developing society, of which she understood children as a central component

49. There is also an interesting question of political affiliations, Key was a committed, and a times radical, socialist, Brigham….. you’ve got to assume she was left leaning but she never appears to have made any statement or declared any political affiliation…..

50. In Box Furniture there is a set of nesting benches and/or nesting tables (page 184), which Brigham notes were used in Sunshine Cottage, and which can be (partially) seen in a photo in Sunshine Cottage, Ideal Home (FN 26), and which in terms of form, reduction, functionality and space-saving concept are outrageously modern. And that in ca. 1902. And crafted from recycled packaging waste….In ca. 1902….

51. Ellen Key, Beauty in the Home, translated by Anne-Charlotte Harvey, in Lucy Creagh, Helen Kåberg & Barbara Miller Lane [Eds.] Modern Swedish Design. Three founding texts, Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, 2008 page 41

52. Louise Brigham, Box Furniture. How to Make a Hundred Useful Articles for the Home, The Century Co, New York, 1909, Preface (unnumbered)

53. Brigham’s correspondence with the Larssons is maintained in the Carl Larsson Archive at Uppsala University Library, we have had no opportunity to explore it, but suspect it will provide the necessary information to support or negate our theory ….. Also important to note that we’re trying hard to ignore a Washington Post article (Miracles with old boxes, handiwork of a woman, August 29th 1909) which notes, that, after Spitsbergen, she went to Norway, and then, “from Norway she went to Sweden, where she studied knife work for six weeks, to Copenhagen …..to Holland and Germany and Vienna and England, always living among the peasants studying their arts and lessons of utility, simplicity and thrift”, and trying to ignore it because it’s far to jumbled, means she did everything after the summer of 1907, and in the terms of the peasants, is probably not 100% true. But it does indicate a possible alternative itinerary

54. sloyd is derived from slöjd, the Swedish for craft or handicraft

55. David J. Whittaker, The Impact and Legacy of Educational Sloyd. Heads and hands in harness, Routledge, 2014, title page

56. Finnish National Framework Curriculum 2004, (translated and???) quoted in ibid page 5

58. According to the Lexington Herald (Sunday October 10th 1909, page 7) Brigham instructed in the making of Box Furniture over a period of three weeks at the W.C.T.U Settlement School in Hindeman, Kentucky, and the same paper reported a month earlier (Wednesday September 22nd 1909, page 12) that Brigham also spoke to the school authorities in Lexington and Louiseville about the possibility of staging courses in their schools. We (currently) have no evidence she tried any where other than Kentucky, but you’ve got to assume she did…… Also important to note it is 1909 and thus prior to Gracie Mansion, implying the move to teaching packing crate furniture production rather than just demonstrating packing crate furniture occurred immediately upon her return from Europe, i.e. was decided upon in Europe.

59. see Antoinette LaFarge, Louise Brigham and the Early History of Sustainable Furniture Design, Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2019 page 77-83 for more on Brigham and the (hi)story of flat-packs. Also important to note that flat-pack furniture involves the development of a specific construction system which allows anyone with minimum technical skill to build the object. And it can’t be taken for granted that Brigham’s packing crate approach would have been 1:1 transferable to flat-pack… and so did Brigham develop a new construction system, and if so how did it work? Flat-pack also requires a different design approach.

60. Brigham also appears to have had a company called “Louise Brigham Box Furniture” which may or may not have sold objects made from boxes (see, for example, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle Wednesday March 28th 1917, page 24) A Home Art Masters advert in the Los Angeles based Evening Express (Friday November 10th 1916, page 9) heavily implies that Louise Brigham Box Furniture and/or The Home Art Masters had a presence in the so-called Brack-Shops building/galleries in downtown Los Angeles. There was also a company called Louise Brigham Home Arts, San Francisco, which may or may not have been incorporated in conjunction with the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, but which forfeited its charter in June 1916, see The San Francisco Examiner, Sunday June 25th 1916 8E (business pages) … Still a lot of work to be done on fully discerning the exact nature of her commercial interests. And why they all failed.

61. Bernice Griswold, What women are doing to help win the War, Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 29th 1918, page 50

62. Cleveland Plain Dealer January 25th 1903 page 28, for example, lists Mrs Henry Chisholm as helping at the Sunshine Cottage housewarming on Hamilton Street. Same article also lists a Miss Virginia Graess as being present, which may or may not be the the Miss Virginia Graeff thanked in the forward to Box Furniture for “valuable help and suggestions”

63. Eleanor Clarage, Main Street Meditations, The Cleveland Plain Dealer, Monday February 4th 1929, page 20

64. For more on Louise Brigham and Edgar Cayce see see Antoinette LaFarge, Louise Brigham and the Early History of Sustainable Furniture Design, Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2019 page 91 – 98

65. Given that Brigham was in Europe to study contemporary and vernacular craft practice and interior design, and that for 4 years, it appears reasonable to assume she made notes, wrote some things down, made a few sketches, possibly kept diaries…. if only those could be located….. In later life Brigham apparently planned numerous, never completed, book projects. In our fantasy they are books collating impressions and recollections of early 20th century Europe. And are wondrous treasure troves which help us all approach more probable understandings of early 20th century design…….

66. see, for example, Don Marek, Arts and Crafts Furniture Design. The Grand Rapids Contribution 1895 – 1915, Grand Rapids Museum of Art, 1987

67. A book of boxes, New York Times June 5th 1909

68. In which context, yes, it is ironic, from a contemporary perspective, the among the more important companies in advancing Brigham’s work were the Astral Oil Works and the Arctic Coal Company…….

69. Paul Feyerabend, Against Method, Fourth Edition, Verso, 2010 page 201

70. Another interesting comparison between Brigham and Chippendale is that both, effectively, had a commercial arm: while you were free to re-produce Chippendale’s designs you could also commission Chippendale to make them for you, which many wealthy individuals did, while The Home Art Masters and Brigham’s other companies produced Brigham’s design so that you didn’t have to

71. Enzo Mari in Hans Ulrich Obrist, The Conversation Series 15: Enzo Mari, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, Cologne, 2008 page 38 Mari also speaks of the importance of “concrete needs – that is, the facility of using it, solidness, elegance, low cost” (page 37) which also fits in very, very nicely with Louise Brigham. And Ellen Key.

72. Among the other projects Brigham refers to in the preface to Box Furniture, but on which can (currently) find no further information, is “Bradley Republic” which may or may not be the contemporary Allendale Association in Lake Villa, Illinois, to the north of Chicago, and which between 1897 and 1909 were busy building their centre for, at that time, homeless and destitute boys. And if so fits in very well with the general plan. Also makes mention of a “vacation home for girls in Connecticut” which is much harder to identify and unclear if the girls made the furniture, if so that would be a real novum in the Brigham (hi)story…..

73. see, for example Bernice Griswold, Store box furniture of Cleveland woman brightens homes in France, Cleveland Plain Dealer May 19th 1918 page 45 and Bernice Griswold, What women are doing to help win the War, Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 29th 1918, page 50 Appears the so-called American Fund for French Wounded had a small project creating furniture from emergency aid crates, and that in New York ladies were trained in the art with the intention that they travel to France to help. Unclear if any ever did. Also unclear if Brigham was directly involved, although the training centre appears to be based in the The Home Art Masters factory space at 16 Horatio Street, Greenwich Village and amongst the ladies training to make box furniture was one “Mrs William D. Munroe of Houghton, Massachusetts”, which is presumably the same Mrs William D. Munroe who was once of Spitsbergen……

74. Neville Thompson, Louise Brigham: Developer of Box Furniture, in Bert Denker [Ed.] The Substance of Style. Perspectives on the American Arts and Crafts Movement, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Delaware, 1996, 199 – 211

75. Antoinette LaFarge, Louise Brigham and the Early History of Sustainable Furniture Design, Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2019,

Tagged with: Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts, Box furniture, Cleveland, Design Calendar, Enzo Mari, Louise Brigham, New York, packing crate furniture, Spitsbergen, Thomas Chippendale