#officetour Milestones – The Modern Efficiency Desk

In his 1917 novel The Job Sinclair Lewis makes note of a group of ambitious young clerks who work in the offices at Pemberton – “the greatest manufactory of drugs and toilet articles in the world” – and who sat at “shiny, flat-topped desks in rows”.1

And you’re all currently thinking, yeah… and… ???

……. and… while that may be a valid response today, in 1917 ambitious young clerks sitting at rows of “shiny, flat-topped desks” were, when not a revolution, then a relative novelty, and for all were highly indicative of a period of fundamental evolution and development in understandings of the office, of office work, of office workers, of office desks. A period of fundamental evolution and development that continues to inform the 21st century office. And the 21st century office desk…….

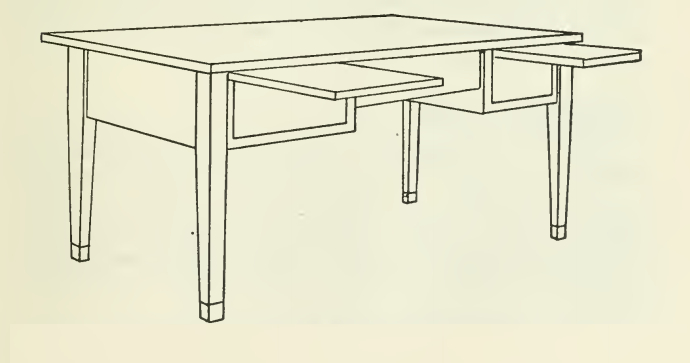

#officetour Milestones – The Modern Efficiency Desk (Image from Lee Galloway, Office Management. Its Principles and Practice, The Ronald Press Company, 1922)

Although in the Europe of centuries past desks for home use often had a flat surface, indeed the very first desks would have been so-called “tables”, the fact that until the second half of the 19th century commercial offices as we understand them today didn’t exist meant that neither did the commercial office desk; those who undertook what we understand today as “desk work” generally employing a raised standing height object with an inclined surface, an object required by necessity as working in and with the large folios of centuries past is neigh-on impossible on a flat surface.

Then as the 19th century moved ever closer to the 20th the commercial office as an institution began to appear, arguably arising first, and fastest, in North America, Philip Carlino noting that “the clerical workforce in the United States grew from 81,619 in 1880 to 740,486 in 1900 and more than three million by 1920”2, an expansion driven by increasing industrialisation and globalisation; an expansion which led to an increasing division of labour within the office, tasks that had once been performed by a single employee being actively separated and performed as separate tasks by separate employees; an expansion which saw the folio replaced by the ledger and the index card; an expansion which changed the practices and rituals of the office; an expansion which changed the role and function of the office. And an expansion which demanded new office furniture. Not just new furniture for the increasingly specialised office workers, nor only for the new practices, tools and materials of the new office, but also for defining office hierarchies: whereas in the small offices of the early 19th century with their two or three members the position of each in the hierarchy was clearly defined, and of only marginal importance because it was so explicitly understood; in the expanding offices of the late 19th century with their two or three hundred members, and for all through the increasing layers of middle management the new work practices spawned by way coordinating the new work flows, furniture was sought that allowed differences in rank and status to be both identified and confirmed. For lest we forget, in late 19th century America rank and status were highly prized and closely guarded commodities.

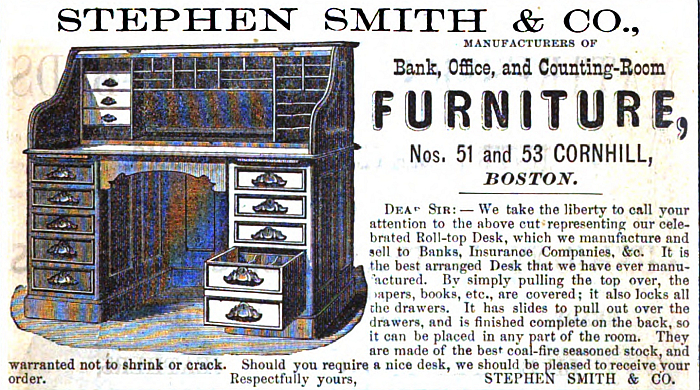

One of the more universal manifestations of the search for hierarchy affirming office furniture was the establishment of the roll-top desk in commercial offices. In many regards based on earlier centuries’ domestic writing furniture, roll-top desks, as the name implies, featured3 as a defining detail a rolling top, a construction of wooden slats which allowed the user to close, and lock, the desk when they left the office. The rolling top was however but one defining detail of the roll-top desk. And neither by nor in itself the most important. Of equal importance was that roll-top desks were, generally, large, imposing objects, occasionally ornately decorated, often crafted from high-value wood, and thus objects which established an assertive presence in a room, a presence which, as Adrian Forty notes, “encapsulates the responsibility, trust and status given to some clerks”4; in addition, and of equal importance, roll-top desks featured a high back which extended above the sitter and which, combined with the raised side panels necessary for the rolling top, endowed the user a degree of privacy, hid the desk’s surface from the casual gaze of others, and thus as Christine Schnaithmann opines granted the user “the privilege of private space”5, created a room-within-a-room in an open-plan office space, and thereby further underscoring the distinction of senior staff from lower ranked employees. Lower ranked employees who often worked at standing height objects with an inclined surface, for lest we forget developments and evolutions of office furniture, as with all furniture and architectural developments and evolutions, are never sequential but always aggregative, cumulative; or lower ranked employees sat at flat desks which with their heavy pedestal bases resembled the roll-top desks save without the high back or lockable rolling top, and thus without the privacy afforded their superiors.6

Beyond their role as confirmers of status and rank Carlino argues that roll-top desks, and their non-rolling companions, were also about storage of information7; the commercial office arising both in conjunction with an increasing amount of paperwork, the typewriter, for example, arriving in commercial offices at that period, and also arising slightly before the development of centralised filing and documentation systems, and thus placing responsibility for the management of all documents, and thus the operations of the company, with individual clerks. A responsibility the roll-top desk on account of its other defining, and equally important, detail, namely its profusion of drawers, cupboards and pigeonholes, aided and abetted the respective clerk to fulfil.

A profusion of drawers, cupboards and pigeonholes which made the roll-top desk, and its non-rolling companion, as much a multi-functional workspace as a desk.

And a profusion of drawers, cupboards and pigeonholes which would increasingly become an anachronism as the 19th century became first the 20th and subsequently the 21st.

An 1870s advert for Stephan Smith & Co, Boston, an early producer of commercial office roll-top desks (Image from The Boston Directory)

The developments of the late 19th century were largely concerned with maximising efficiency in the new office world, of establishing procedures and processes to enable the small offices of the past metamorphose into the large offices of the future; early efficiency experiments which, as the 19th century ceded to the 20th, became formalised in Scientific Management.

Originating in context of factories Scientific Management deemed that every task could be optimised, and through optimising every task the efficiency, the productivity and the profitability of a factory could be increased. And which in its transfer from the factory to the office (generally) took a position that understood the office as analogous to the factory, office workers as analogous to factory workers, and the office desk as analogous to the factory work bench.

A comparison intensified by the increasingly widespread adoption in the early 20th century of centralised documentation systems, the genesis, if one so will, of the age of the filing cabinet; a development necessitated by the ever increasing size of offices, by the ever increasing complexity of office work flows, and a development which greatly impacted on the required functionality, and understandings, of the commercial office desk: the profusion of drawers, cupboards and pigeonholes of the roll-top desks becoming not only unnecessary but posing a very real risk to the efficient running of the office.

And a comparison which had fundamental consequences for the status of the office clerk; whereas the office worker of the early 19th century, as with the craftsman of pre-industrial workshops, was entrusted and trusted with responsibility for a wide range of duties, often encompassing the entire production/office process, the office worker of the early 20th century was responsible for fulfilling their one single task, and that repetitively and often unaware of that task’s position in and relevance to the wider operation of the factory office.

A development which as Dale A. Bradley opines “marks a transitional moment in the clinical gaze of the office wherein control over work shifted from the individual to the system, which is to say, from worker to workflow”8; if one so will a shift to an industrialisation of office work and where the office worker became understood as but a cog in a machine, responsible for nothing more than the smooth transfer of paperwork.

A shift which for Bradley “is made manifest in the development of a new worker—desk assemblage”: the Modern Efficiency Desk.

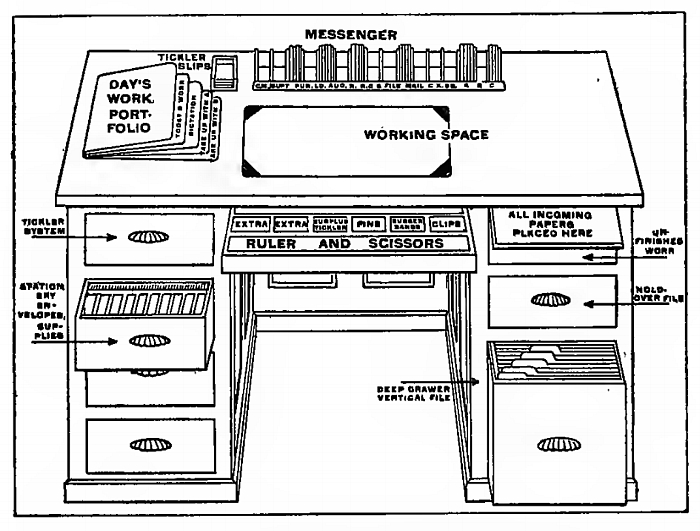

A standardised desk management system (image from P.W. Lennen, with the collaboration of the editorial staff of System, How to Double the Day’s Work, The System Company, Chicago, 1910)

The arrival of the, so-called, Modern Efficiency Desk is generally dated as 1915, specifically with a desk developed for the Equitable Insurance Company’s new office building in Manhattan9, a work poetically described in 1918 by Lee Galloway as “little more than a table with three shallow drawers”10; whereby the shallowness of the drawers was of particular importance to Galloway as it meant, “clerks cannot stow within it papers which will later be overlooked”, and that “as there is no room for placing current work in the drawers, any tendency to defer until tomorrow what can be done today is nipped in the bud”. An understanding of the evils of the desk drawer succinctly framed by Adrian Forty in his opinion that, “Scientific Management had a general, at times pathological, hatred of desk storage space”.11

An aversion combined with an almost pathological passion for efficiency amongst proponents of Scientific Management which meant that the desk of the early 20th century, in contrast to the desk of the late 19th century, was “no longer a storage place — nor even ornamental — but a tool for making the quickest possible turnover of business papers”.12

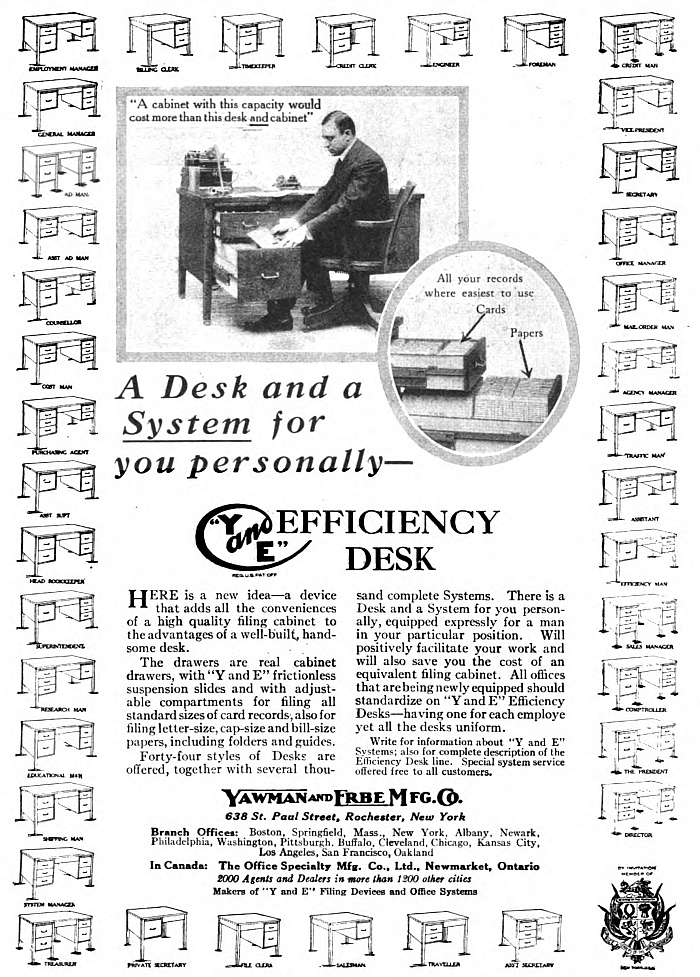

A tool of which a great many models were designed and produced in the 1910s and 1920s, all of whom sought to aid the “quickest possible turnover of business papers” not only via their want of storage space but also via that other great credo of the early 20th century: standardisation.

Specifically standardisation of construction and of use.

“In all the category of earthly subjects there is no better example of a really good thing gone wrong than the much-misused and much-abused desk drawer!”, exclaimed in 1910 the authors of How to Double the Day’s Work13, and for all the large file drawer often found at the bottom of the pedestal leg which, in their opinion, “”from time immemorial” this compartment in the desk has been totally misused and unappreciated … its ample proportions have been shamelessly used as a convenient annex to the waste bucket, or a sort of second scrap heap, rather easier of access than the one in the back yard”. Thereby indicating that for Scientific Management the problem wasn’t the profusion of drawers, cupboards and pigeonholes, but clerks.

Thus late 19th/early 20th century efficiency protagonists developed and advocated strict, standardised, systems of drawer use, standardised systems which strictly defined what was to be kept in which drawer, standardised systems of drawer use to be strictly used by all clerks thereby nipping in the bud the myriad problems caused by clerks, by individual decision making; and standardised systems of drawer use which as the number and scale of drawers were reduced became strict, standardised, systems of desk top use, standardised systems which strictly defined what was to be placed where on a desk top, and standardised systems to be strictly used by all clerks, for as John William Schulze opines, in terms of desk organisation “when it is left to employee’s own devices a tremendous loss of efficiency results”.14 So they weren’t. Which aside from (allegedly) aiding efficiency also meant that standardised desk tops, cleared of all unnecessary baggage, shone in a way their predecessors couldn’t.

And a standardisation of desk tops encouraged and advanced by the use of standardised models; while drawers were unquestionably dangerous they were still necessary in the early 20th century office, and different jobs required different drawers, thus many manufacturers of the period produced ranges of desks with differing drawer combinations and configurations, yet all of the same size, material and construction15; thereby not only easing the strict enforcement of standardised desk top usage, but, and as Schulze opines, standardised desks of the same basic model “have a good general psychological effect. The appearance presented by a uniform desk equipment throughout the office suggest the existence of well ordered methods. It is notice to the employee that the same care and regard for order will be required of him. Various kinds and shapes and an irregular arrangement of desks suggest, on the other hand, that there is no general scheme of supervision that is in harmony with well founded principles”.16

“An irregular arrangement” of “various kinds and shapes” of desks which could only impact negatively on the efficiency of the office machine; thus, the office of the early 20th century was, certainly ideally, an environment populated by disenfranchised, if often ambitious, clerks sitting at rows of “shiny, flat-topped desks”.

A 1916 Yawman & Erbe Mfg. Co. advert for Efficiency Desks in with a variety of drawer combinations for differing jobs (Image from System. the Magazine for Business, June 1916)

We can’t be 100% certain what the “shiny, flat-topped desks” used by Pemberton’s ambitious young clerks looked like, were it a Zola novel we’d know down to the tiniest detail, Sinclair Lewis leaving it more open; however, not only the image awoken by the description but also the number, and nature, of references Lewis makes in The Job to not only desks, both flat and roll-top, but also to office equipment and office efficiency, the latter viewed both positively and negatively, tends to imply that he was very much aware of and very much had in mind the optimised office of Scientific Management. And thus the near drawer-less Modern Efficiency Desk. And that in 1917 when the Modern Efficiency Desk was still very new.

Or new old, for the Modern Efficiency Desk is in many regards just a table, an early form of flat writing surface that had to be re-invented in the early 20th century for the contemporary office.

Or perhaps more accurately, the commercial office had to develop to a position where the Modern Efficiency Desk, the table, became a meaningful, practical, desirable solution.

A development of the commercial office in the late 19th/early 20th century not just in context of ever evolving workflows, office practices, office equipment, office materials, divisions of labour, et al, reducing the desk down from an active multi-functional workspace to a passive, mute work-surface, but also in context of that other other great early 20th century credo: hygiene. Not only do flat top desks improve the distribution of light and air within the office space as compared to their high-backed roll-top predecessors and thereby help induce a healthier office environment, but they also allow for improved cleaning of the office, both on the standardised desk tops and also under their standardised frames: their reduction in function allowing a reduction in form which saw the heavy drawer-laden pedestals of yore become four thin legs. Schulze telling, and epoch conform, refers to Modern Efficiency Desks as “sanitary” desks in contrast to the older

.17unsanitary

type

Thus for all that the Modern Efficiency Desk can appear a step-backward, can appear but a return to the tables of centuries past, they are and were very much objects of their age: objects that could only have arisen at that time, objects that evolved from and in conjunction with the evolving social, economic, technical, mercantile et al practices and realities of the period18, evolved from evolving understandings of the office, of office work, of office workers, of the period19, evolved from understandings of the role and function of the individual in society at that period.

And thus are objects which can teach us an awful lot about the relationships between our objects of daily use and contemporary realities, contemporary society.

But for all, and arguably above all else, the Modern Efficiency Desk stands as a genuine milestone in the history of office design.

A milestone on account of the continuation of the understandings of the form and the function of the commercial office desk inherent in the Modern Efficiency Desk to our current age; a continuation which helps underscore how the positions and understandings of the early 20th century continue to inform our contemporary understandings; a continuation which has seen us complete and consummate the removal of drawers and storage space begun in the late 19th century while maintaining the basic formal idea of the Modern Efficiency Desk and thereby advancing, optimising, the standardisation of rows of “shiny, flat-topped desks” that, a century and a bit later, still largely define the contemporary office.

And a milestone on account of the understandings of the office, of office work, of office workers which led to the rise of the Modern Efficiency Desk. The fact that the Modern Efficiency Desk arose in a considered, processual, manner at a period when, and to marginally, but not inaccurately, misappropriate the Vitra Design Museum’s 1993 exhibition Citizen Office, society stood on “the threshold between criticism of existing convention and, as an option, examples, of a future office landscape”20, stood on a threshold between the office, office work, office workers past and future, a threshold we also find ourselves on, allowing reflections on the hows, whys and wherefores of the Modern Efficiency Desk to inform reflections and considerations on our contemporary, and future, offices, office work, office workers. And thereby our future office desks.

1. Sinclair Lewis , The Job, Jonathan Cape, London, 1926

2. Philip Carlino, Docile by design: commercial furniture and the education of American bodies 1840-1920, PhD Thesis, Boston University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2020

3. We talk of the roll top-desk in the past tense, but clearly they still exist today. The past tense is simply used to ease readability.

4. Adrian Forty, Objects of Desire. Design and society since 1750, Thames and Hudson, London, 1995

5. Christine Schnaithmann, Das Schreibtischproblem. Amerikanishe Büroorganisation um 1920 in Lars Bluma and Karsten Uhl [Eds.] Kontrollierte Arbeit – disziplinierte Körper? Zur Sozial- und Kulturgeschichte der Industriearbeit im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, 2012

6. Important to note that in the late 19th century flatter topped, formally reduced desks were often used by female typists, the late 19th century marking as it did the widespread arrival of the female in the office, an arrival that also impacted greatly on office practices and design, and an arrival for another post. A post that may very well bring us back to The Job.

7. see, Philip Carlino, Docile by design: commercial furniture and the education of American bodies 1840-1920, PhD Thesis, Boston University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2020

8. Dale A. Bradley, From Wooton to Workstation: Mechanisms of the Visible in Office Spaces, Journal for Cultural Research, Vol. 11, Nr. 4 , October 2007

9. One often reads that the Equitable Insurance Company desks were supplied by Steelcase. We can’t locate a source to confirm that assertion. And while it may very well be true, we may just be looking in the wrong places, aside from the fact that in 1915 Steelcase were still called Metal Office Furniture Company, Steelcase themselves don’t repeat that claim: the Steelcase online archive presenting a desk from 1915 that while of a reduced a Modern Efficiency Desk type, isn’t that model Galloway implies was used by the Equitable Insurance Company. In addition one must add not only as in our footnote 6 that female typists often sat at flat-topped desks, but also that, for example, a decade before the Equitable Insurance Company desks Frank Lloyd Wright developed Modern Efficiency-esque desks for his Larkin Administration Building, all of which tending to underscore that the development of the Modern Efficiency Desk must be considered a process rather than a defined moment. And also to note that the adoption of the Modern Efficiency Desk was closely related to the adoption of Scientific Management to offices, and thus, arguably, the Modern Efficiency Desk only became visible and discernable as a thing when Scientific Management began promoting them.

10. Lee Galloway, Office Management. Its Principles and Practice, The Ronald Press Company, 5th edition, 1922

11. Adrian Forty, Objects of Desire. Design and society since 1750, Thames and Hudson, London, 1995

12. Lee Galloway, Office Management. Its Principles and Practice, The Ronald Press Company, 5th edition, 1922

13. P.W. Lennen, with the collaboration of the editorial staff of System, How to Double the Day’s Work, The System Company, Chicago, 1910. The System Company were a guise of the Shaw-Walker Co. a company who started with the production of index card filing systems and went on to be important early protagonists in the development of “efficient” office furniture. As part of their strategy they produced the magazine System. The Magazine of Business

14. John William Schulze, The American Office. Its organization, management and records. The Ronald Press Company,, New York, 2nd edition 1914

15. see, Philip Carlino, Docile by design: commercial furniture and the education of American bodies 1840-1920, PhD Thesis, Boston University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2020

16. John William Schulze, The American Office. Its organization, management and records. The Ronald Press Company,, New York, 1914

18. The reduced design also allowed Modern Efficiency Desks to be constructed from metal, a not unimportant consideration in an age when company’s records and files were all stored on paper and fire was ever present reality. Indeed it was a fire at the old Equitable Insurance Company offices that necessitated the building of the new Equitable Insurance Company office that is credited as the birth of the Modern Efficiency Desk.

19. Important to note that hierarchical understandings continued, that although executives’ desks were also reduced, they remained distinct from those of clerks, a distinction and differentiation which had begun in the late 19th century and which would continue until the late 20th century.

20. Uta Brandes; Alexander von Vegesack [Ed], Citizen Office: Ideen und Notizen zu einer neuen Bürowelt, Steidl Verlag, Göttingen, 1994. The authors were referring to a threshold in the early 1990s, but the same applied to the early 20th century, indeed the office can, must, be considered as permanently on a such a threshold, we however generally only understand them looking backwards, rarely in real time. As with so much in life……..

Tagged with: #officetour, Desk, desks, milestones, Modern Efficiency Desk, roll-top desk