Basketry has something of the archaic about it, almost anachronistic, has echoes of a past we've all long moved on from.

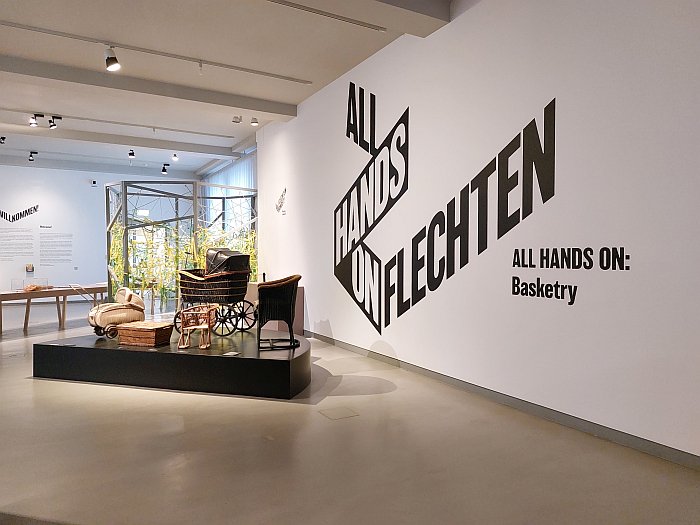

With the exhibition All Hands On: Basketry the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin allow for, demand, a critical reassessment.......

Presenting its narrative over the course of four chapters — People, Protection, Material and Pattern — four chapters which, and at the risk of opening with an unforgivable pun, intertwine.... sorry!.... to enable the construction of a space.... sorry!!.... in which to undertake an exploration of not only the (hi)story of basketry1 but also of the role, function, relevance and symbolism, the ever altering and evolving role, function, relevance and symbolism of basketry in, to and for human societies, or certainly the European societies of the museum's name, raison d'etre, in the course of that (hi)story.

A narrative populated and advanced by explanations and discussions on the tools and methods and processes of basketry and by a selection of some of the myriad products of basketry, products both practical utilitarian and decorative artistic, both ancient and new.

A mix that on the one hand helps underscore that the uses of the products of basketry have changed but little over the centuries, alone the contexts and materials have, and on the other allows one to better appreciate how basketry has helped contribute to the development of European societies, be that in assisting the practices of, and development of, for example, agriculture, commerce, apiary, or balloon aviation, as one learns hot air balloon gondolas are constructed from basketry not only because of the inherent lightness, but because of the natural cushioning they provide on impact, that gentle resilient landing you seek; or in context of clothing, where aside from the ubiquitous straw hats in their endless variety, All Hands On also presents shoes from across geography and time, and also a late 19th/early 20th century grass coat from an unspecified location in the Alps, a work that finds and found an echo a century and a bit later in the Harvest speculative clothing collection produced from plant material and realised in context of the 2023 edition of the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden's Design Campus Summer School, and as last seen in context of Vienna Design Week 2023. A late 19th/early 20th century grass coat that helps underscore that, and as oft noted in these dispatches, the solutions often exist, we've just got to look for them. And recognise them. Similarly the late 19th century rattan vest from Korea, we're presuming from Korea, Asia, not from Korea, Europe, and which was designed to create an air space between clothes and skin and thereby allow for a cooling effect on hot days, an object that for all its unwieldiness has lost nothing in contemporaneousness over the decades and which is another fine example, as Hot Cities: Lessons from Arab Architecture at the Vitra Design Museum Gallery so easily could have been had they not abandoned it early after Der Spiegel got extremely cross and cheeky, of how we in Europe can learn from those who live in hot climates to survive in our coming, self-kindled, furnace.

Or in context of the development of architecture, including making note of the fact that basketry was once the preferred method for wall construction, with the air pockets that are automatically produced providing for a natural insulation, and a process that, by all accounts, is the origins of the, a, German word for 'wall', 'Wand', a term derived from gewunden, wound, twined, wreathed etc. The etymology in English appears to have similar origins, if, and appositely given the nature of out subject, via a much more convoluted path. And while today the use of wooden basketry may be rare in construction, certainly in our European urban spaces, the basis of the reinforced concrete that has replaced it is still a weave, albeit one of steel rods and one that doesn't come with natural inherent insulation. If reinforced concrete that is easier to use and quicker to construct with. Developments can sometimes simultaneously be a step backward and a step forward, a staying in the same place with shift of focus giving the illusion of movement.

And reflections on basketry and architecture also encouraged via a presentation of examples of the use of basketry by non-human animals in their architecture, primarily the various species of the so-called weaver birds, alongside examples of the use of basketry by human animals without the assistance of architects, including examples of the many living root bridges to be found in the forests of the state of Meghalaya in northeastern India, again one presumes India, Asia, and not India, Europe, and alongside examples of the use of basketry by human architect animals such as the proposed Haus der Zukunft, House of the Future, in Berlin by Office for Living Architecture, OLA, a composition in steel, glass, concrete and trees as a union of the nature constructed world and human constructed world to a single inseparable entity. A three way juxtaposition that reminds, as with the 19th century Korean rattan vest and architecture in north Africa and on the Arabian peninsula, that European human animals don't have to invent everything from scratch in order to exist, we can learn from that which is done outwith Europe and outwith the human species. And doing such doesn't make us any less capable, but perhaps, hopefully, a little less culpable. And a juxtaposition that also allows one, forces one, to question if architects are actually necessary for the development and construction of our spaces of habitation. A question also posed by the existence of the profession of the Civil Engineer. And thus a component of that discussion on what is architecture and what are architects?

And a mix of basketry as anonymous vernacular and as the basis for international design that runs through All Hands On. Alongside baskets, bowls, crates et al of an apparently infinite variety, All Hands On also presents, for example, and amongst others, vases from the project The Resonance of Raw by Berlin based designer Thalea Schmalenberg [and, we're assuming, certainly judging by the photos, a (regrettably) unnamed glassmaker] in which hot glass is blown in wicker moulds to leave an undulating surface, that, we presume, we (very sensibly) weren't allowed to touch them, bequeaths a tactility every bit as engaging and communicative as the visuals; or the rattan chairs designed by Bernhard Pankok in 1919 for the Zeppelin 'Bodensee', a Bernhard Pankok who, as previously noted, was responsible for all the furniture and interior design of the earliest passenger Zeppelins; and rattan that was employed in those flying visions of the future for its lightness before being replaced by the lightness, painfully forward looking gaze, and future secure invincibility of, tubular metal2, that unequivocal symbol of 20th century progress. If, as the curators tend to imply, the cushioning qualities of basketry, that which means it its still used today in balloon gondolas, those humble, unassuming, relatives of Zeppelins, would have made Pankok's chairs more useful in context of, the one presumes inevitable, bumpy landings than the rigidity of tubular metal. Would steel tube cantilevers have helped?

And flying rattan chairs by Bernhard Pankok that are just one of an an array of seating objects to be found in All Hands On, including an Orkney Chair, a object tenaciously balanced between vernacular and design, an object that, as previously discussed, while its distribution, ubiquity, in the Orkneys before the late 19th century is as questionable as all other Orkney Sagas, is highly informative in context of the development of furniture, and as an object is thoroughly practical for life in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean; or an unfinished stripped willow chair begun by Wolfgang Jacob in East Berlin in 1982. A chair that in its incompleteness, and the apparent ease with which it can be unravelled, could be construed as a subtle criticism of the state of the DDR thirty years after its founding; a chair that is certainly never going to be completed today, which somehow adds to its value and resonance; but also a reminder that for all the DDR is often associated with anonymous industrial production, individual craft production did exist in the DDR, and arguably it was a solid craft basis which enabled the production of a chair such as the EW 1192 at such remarkable industrial levels. And a work that in its illustration of the process of weaving willow strips to form an chair enabled by its incompleteness elicits easy comparisons with the work of English manufacturer Full Grown who grow chairs directly in willow. Which, arguably, is an example of extreme basketry.

Or a Thonet child's armchair Nr. 4 from ca. 1900 with is fine geometric rattan Wiener Weave seat, and a 1980s kitchen chair from Portugal with a much coarser rush weave, presented in unison by way of introducing various types of weave used in the production of chair seats and backrests. The Portuguese version of which very much reminding of the woven rush seats of the vernacular Italian chairs that inspired and informed the woven rush seats of Kaare Klint's chairs for the Bethlehem Church in Copenhagen, and very much reminding of the seats of Gio Ponti's Leggera/Superleggera, or of an Egon Eiermann's SE 19 originally for the Matthäuskirche, Pforzheim. An Egon Eiermann who, as with the DDR of which he was so nearly a citizen, for all that he is associated with industry wasn't adverse to craft; an interest in craft most popularly known in his family of rattan furniture, objects developed together with and produced in the workshops of Heinrich Murrmann in Johannisthal-Kronach, Oberfranken, a long established manufacturer and that in region with a long tradition of basketry, the nearby town of Lichtenfels being one of the primary centres, and which since 1904 has boasted of a basketry college.

And while we are currently unsure as to the exact source of the bondoot rattan employed by Eiermann and Murrmann in the 1950s, but are very much on its trail, we are sure that the rattan palm isn't native to Europe. Nor was it the late 19th century and early 20th century when it was widely used across the continent. Rather rattan was a colonial good.

A colonial (hi)story of rattan, links between basketry and colonialism, basketry as a further example of the European Cultures of the museum's title as culpable, explored and discussed in All Hands On via a brief discussion, introduction, undertaken in the company of, for example, and amongst other exhibits, a 1950s sales aid for Bremen based rope manufacturer F. Tecklenborg & Co. with its photos of African sisal farms and production facilities, by early 20th century collector's cards glorifying German colonisation in Africa or by P. C. Ettighoffer's 1943 book Sisal. Das blonde Gold Afrikas. Die tat des Dr. Hindorf, [Sisal. The blonde gold of Africa. The deed of Dr. Hindorf], a book we've admittedly never read but which we very much get the impression the "tat" of the title could also be translated as 'exploit' as in 'exploitation', 'exploitation of Africa enabled by Dr. Hindorf through his highly questionable transfer of sisal from Mexico to Africa in the name of colonial agriculture and providing raw materials for German industry'. And thus a book that is both a reminder of that individual who did more than most to establish sisal in Germany's colonies, and by extrapolation in contemporary Africa, and which also helps underscore not only that blindness to the consequences with which we in Europe can pursue economic goals, nor only the resilience and legacy of the Colonial lies, but also the contemporary dangers of glorified, one-sided, European, interpretations of (hi)story: by 1943 the NSDAP were almost at an end, but their ideology was clearly still very buoyant. And, by all accounts, we never met him, P. C. Ettighoffer was a near perfect embodiment of that nefarious, infernal ideology.

And sisal that also take a central role in Nairobi based artist Syowia Kyambi's installation The Green Gold, alongside Sansevieria trifasciata a relative of sisal native to the African continent, in a composition that weaves components from the various narratives of the (hi)story of sisal cultivation and production in Germany's colonies in Africa through components of the biography of Sansevieria trifasciata. And where green gold and blonde gold sit tantalisingly close yet estranged.

A brief discussion on basketry and colonialism which, in many regards, and depending on the path you take through All Hands On, begins with a presentation of the materials of basketry, a presentation which helps explain that Europe has, and always has had, a plethora of options for materials for basketry, but still felt it necessary to exploit other nations and peoples for the benefit of the European economy, for European growth, for European comfort. It's not as if we're short of birch or willow in Europe, or the numerous plant species from which the generic material Bast can be won, that material that, amongst many others, an Else Mögelin used so effectively against the limitations and privations of early 20th century Europe, when other materials were lacking. But that wasn't enough, we wanted that which was on other continents and rather than cooperating took. Including taking from Mexico to eastern Africa.

And a brief discussion on basketry and colonialism, that is also very much an unmistakable admonishment to us all to concern ourselves more with late 19th/early 20th century rattan as a colonial good, a good invariably won through colonial exploitations. A process that you can initiate via the many late 19th/early 20th century rattan objects on show in All Hands On, including the aforementioned fine geometric Wiener Weave Thonet seats: Thonet may have employed large numbers of homeworkers to produce their seats in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and thereby provided extra income for a great many families in their various production locations, they may have been advanced greater social responsibility in corporate structures in terms of the treatment on their workers in Europe. But where did the late 19th/early 20th century rattan for their Wiener Weave come from? And how? That the majority of the Thonet archives have long since been lost to war, answers will be neigh on impossible to come by, but that doesn't mean the questions shouldn't, needn't, be posed. Nor those of Egon Eiermann's 1950s bondoot rattan.

Beyond its elucidations and discussions on the (hi)story of basketry, the products of basketry and the roles and functions of basketry, All Hands On also helps elucidate the singularity of basketry in human societies, including its existence, in many regards, as something that can only be performed by humans, or certainly a process that requires human input in context of the construction of 3D vessels, baskets,..... from natural materials; the last restriction being decisive for as All Hands On allows on to appreciate the development of novel materials allows for, will allow for, allowed for, the development of mechanised production of basket goods; something exemplified by a so-called Lloyd Loom chair from the late 1930s, so-called because it is crafted from a novel material developed in the early 20th century by Marshall Burns Lloyd from kraft paper and metal wire to realise a material which looks a bit like willow, and which is weavable, loom-able, machine basket-able. A capability also promised by Flignum, a contemporary novel material developed at Kassel University and which is, essentially, an elongated thread of connected strips of willow; thus a material which doesn't just look like willow, but which is willow, and which, we're very much assuming, allows machine production of basketry goods of all sorts. And thus a not uninteresting potential future production technology.

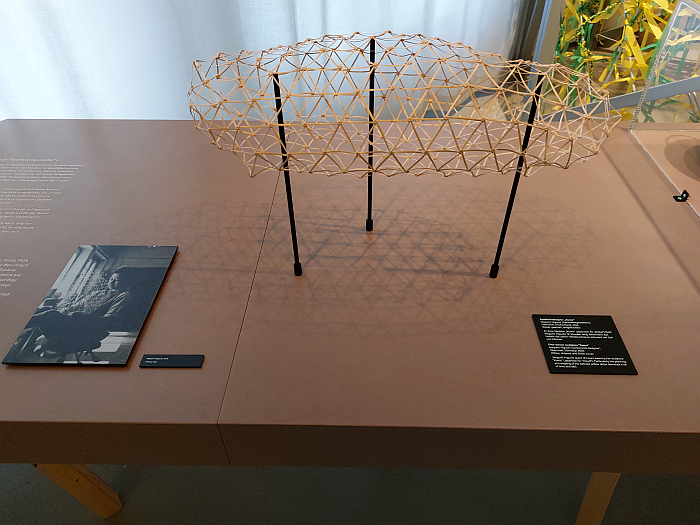

As is basketry with traditional materials being as it is one of the few human employed production processes that can be carried out with materials as found, doesn't require the prior processing of wool or metal or glass, far less the mining, a fact that links neatly back to other animals, is why weaver birds can perform such intricate basketry; and a use as found which can be experienced in All Hands On in Olaf Holzapfel's installation The Woven Garden, a collection of willow forms displaying different geometries, different curvatures, different weaves, different willows, that despite, ¿because of?, their differences unit to create a coherent whole, and which helps underscore that basketry with unprocessed materials is one of the lowest impact processes we can employ for constructing at all levels and scales, negating as it does the need for the resource heavy pre-production stages. And with, for example, willow one has a fast growing, low maintenance, readily renewable resource. And that in Europe, even in the coming European furnace. And which can be also be made into a machinable material. A future-orientated material winnable without violently exploiting and disrupting communities in other continents. Yes, one must be aware of the dangers of monoculture, that thing we're still learning, but, in principle, what's not to like?.

And where could basketry take us?

An accessible and neatly paced exhibition which alongside its coherent bilingual German/English texts and pleasing mix of objects also features numerous practical activities, the Hands On of the title being very much also also a call to action, a call to practice the art of basketry, a call to All young and old alike.

A presentation which despite its European focus never forgets that basketry is a global practice; but which through the concentrated focus on the role, function, relevance and symbolism in a European context allows for reflections beyond the objects themselves that wouldn't be possible with the necessary simplifications and generalisations of a global review. Or certainly would be less in the foreground.

A presentation which alongside its principle narrative also makes a commendably brave effort to compare basketry with contemporary interwoven, intertwined, interdependent human society, an interesting and well made argument; but for our part we still prefer the analogy of the fabric of global society, the warp and weft employing their differences to ensure a stable, durable, whole. Whereby the one question All Hands On doesn't approach, unless that is we missed it, is the one of the distinction between weaving and basketry. Is there one? Is it material specific? Is it to do with 3D versus 2D, and if it is, is 3D weaving just basketry under a new name? But that's something to busy yourself with at a later date.

A presentation which also develops a very nice framework..... sorry!!!.... in which to reflect upon what basketry and the long human relationships with basketry can teach us about European human societies' relationships with other global societies and with the planet we call home; that heavy implication inherent in All Hands On that we Europeans have to learn to reflect more honestly on the world and stop forgetting that when we want things that aren't native to Europe that that has to be done fairly. We may not be as appalling in the sourcing of our rattan as we once were, but our egoistic demand for avocados, turmeric, quinoa, açaí berries, and other things popular on Instagram and TikTok, isn't without consequences. And changing that, changing attitudes, requires All Hands. And maybe a little more basketry. A little less social media.

But for all All Hands On makes a very strong case for more nuanced and serious reflections on the long (hi)story of basketry, on the relationships between basketry and human societies, on the ever altering and evolving role, function, relevance and symbolism of basketry, and thereby on the potential long-term benefits of maintaining basketry as a contemporary, quotidian, practice. On basketry not as something we've all long moved on from, but as something we can all long move forward with.......

All Hands On: Basketry is scheduled to run at the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Arnimallee 25, 14195 Berlin until Sunday May 26th.

Full details, including information on th accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.smb.museum/all-hands-on-basketry

1The original German title is All Hands On: Flechten. 'Flechten' which the curators have translated as 'Basketry', and which we have no argument with. However, 'flechten' is also more generally braiding or plaiting, and such both the flatter constructions that one may find in the form of, for example, a chair seat or a piece of cloth, but also 3D spaces such as baskets. For reasons of readability we've use 'basketry' throughout, but in many cases words such as 'braid' or 'plait' maybe more appropriate. Feel free to substitute words yourself if and when it helps......

2We're assuming the chairs were crafted from aluminium, everything else was, but we are currently having difficultly confirming that, once we have we'll update.