It is a universally acknowledged fact that men only buy Playboy to read the articles.

And we only visited the exhibition "Playboy Architecture, 1953-1979" at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt in order to, to, to, tttoooooooo see the Eames DCW that is on display.....mmmm...... its not a chair you see that often..... aaahhh......mmmmmmmm..... or the Bertoia Diamond Chair?

[Audible nervous cough. Depart stage left.]

Originating from a project by students at Princeton University under the guidance of the architecture historian Beatriz Colomina, Playboy Architecture, 1953-1979 seeks to explore Playboy magazine's role in disseminating contemporary architecture and design. Since its première in 1953 Playboy has frequently covered contemporary architecture and design subjects and so, according to the students theory, helped bring the new ideas of 1950s, 60s and 70s architecture and design to a wider public, and specifically to a public composed of those with the money and influence to help spread the message. And so help move American architecture and design on from the staid pre-war concepts towards lighter, modern styles.

Playboy Architecture, 1953-1979 presents the results of the students research in form of photographs, architectural models, magazines and items of furniture divided into six broad thematic categories.

To begin with however, yes, there is no escaping the nudity nor the widely known if not widely accepted Playboy representation of the female. Not least because the central area in the exhibition space has been converted into a sort of library featuring a complete collection of all Playboy magazines published from 1953 to 1979 for visitors to peruse at their leisure. And pleasure.

No, honest.

Does that matter? Should that matter? Can one look beyond the nudity and inappropriate visual imagery and concentrate on the architecture and design? Distance oneself from the objectification?...... No. Of course you can't. Don't be stupid.

When, for example, you want to check in the September 1970 edition to see what the authors had to say about "portable playhouse" architecture, you can't help noticing that the same edition includes "A loving look at the no-bra look"

However, having viewed the exhibition you do realise that the academic position from which the project arose does have a validity, and as such project and exhibition are perfectly valid.

We would just have preferred it if rather than ignoring the magazine's wider context, that the curators had split the exhibition into two components: one looking at the serious, sensible coverage the magazine gave contemporary design and architecture. And one looking at naked women perched on chairs.

And then compared, contrasted and drawn some form of conclusion

We don't want to get all sociological on you. It would just have been better.

Despite any and all objections to the form of female representation on show, the exhibition ably demonstrates that over the period in question Playboy did cover architecture and design with a degree of seriousness. If a lower degree of regularity.

They, for example, only published one full length piece that dealt directly with contemporary American furniture design; the July 1961 article "Designs for Living" from John Anderson, and which was accompanied by a double page photo of George Nelson, Charles Eames, Edward Wormley, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia and Jens Risom each sitting on/standing next to an example of their craft. All in suits. One must add. And one must also add that it is a very well written and serious article. Not just a collection of "Enjoy the curves on that!", "form follows function!!!" innuendo, but a genuinely well written piece that could conceivably help make the subject of 1960s furniture design clear and understandable. And is in many respects a better piece than most contemporary articles you are likely read on the period and its designers.

In addition throughout the 1950s, 60s and 70s Playboy featured regular-ish interviews with architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Buckminster Fuller, Mies van der Rohe, presented regular features on home electronics, Hi-Fi and other lifestyle accessories and had an almost childish fascination with 1970s fantasy "UFO" architecture. But perhaps most interestingly and most relevantly Playboy regularly published their own vision of the ideal bachelor pad for the suave, sophisticated man about town.

In many ways similar to all those nauseatingly awful "home lifestyle" features magazines are full of today, just much better.

Starting with an idealised "Playboy Penthouse Apartment" in 1956 and moving over, for example a "Weekend Hideaway" or a "Duplex Penthouse", the zenith of the project was unquestionably reached with the publishing in 1962 of plans for a Playboy Town House. Created by R. Donald Jaye the construction was published with the tag line "Posh plans for exciting urban living" and included a swimming pool housed in an atrium with a retractable roof. In addition to sketches and pages from the original article the exhibition also includes a scale model of what could, arguably should, have been. The project was, regrettably, never realised.

Through the presentation of all these projects however one realises just how well, how competently and how self evidently Playboy placed the furniture of the period into a highly stylised vision of the perfect urbane existence.

As we say just like all those nauseatingly awful "home lifestyle" features magazines are full of today. Just much better.

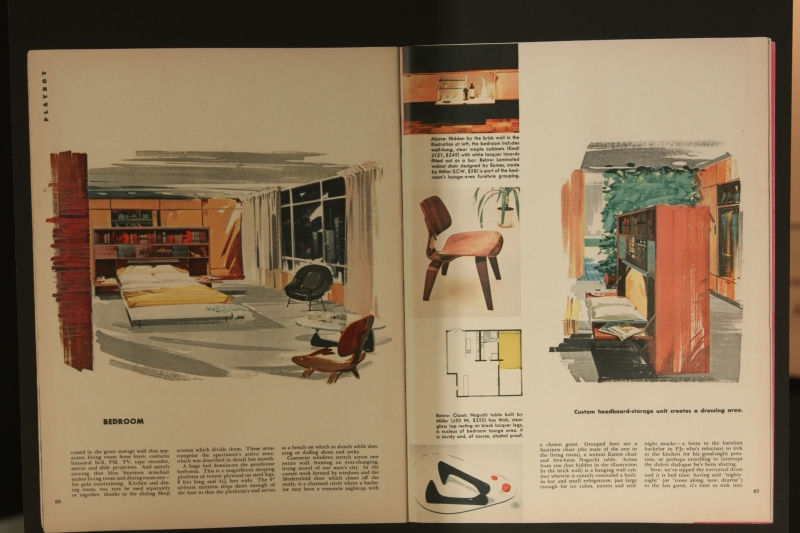

A Nelson bench in the bathroom, an Eames DCW and Isamu Noguchi Coffee Table in the bedroom, or a Saarinen Womb Chair in the lounge of the Penthouse, while the Town House model features, amongst other pieces, an Eames Lounge Chair and ottoman, a brace of Barcelona Chairs and a complete Eero Saarinen Tulip Dining Room ensemble.

Who wouldn't want all that?

As we say, interspersed with such well considered and genuinely interesting features are the photos of women sitting on chairs in various stages of undress and in improbable and not especially comfortable looking positions. Every bit as competently and self evidently presented as the furniture in the Playboy buildings; and images which present a highly stylised vision of the perfect compagnon for the suave, sophisticated man about town.

A parallel which delightfully illustrates from where much of today's over sexualised advertising originates. Today's advertising executives obviously spent their youth stealing dad's copy of Playboy.

Despite presenting a few excellent arguments Playboy Architecture, 1953-1979 fails to provided any scientific, validated evidence to back up the claim that Playboy was or has been central in disseminating new design and architecture thinking. Far less support Beatriz Colomina's assertion that "Playboy made it acceptable for men to be interested in modern architecture and design"

It does however wonderfully explain that the magazine clearly played a role and that it unquestionably helped introduce the ideas and protagonists of the period to a consumer group interested in modern fashion, hot cars, smooth cocktails, careless adventure and naked breasts.

But without any evidence to the contrary we maintain a position that such a group were relatively small and of only marginal significance to the success of Charles Eames, George Nelson et al. Not least because, as the exhibition itself shows, the serious coverage of architecture and design was far too intermittent. Plus there are too many important developments, designers, architects and subject areas from the decades in question that Playboy never covered to allow one to argue that the magazine was "important". Essentially it only presented a very narrow, selective, impression of design and architecture, and one that largely mirrored the magazine's unhealthy infatuation with James Bond.

And the titillating photos are and were intended to transmit just the one idea.

Or put another way, we believe that, for example, whereas most Playboy readers of the period probably remember the image of November 1954's "Playmate of the Month" reclining, carefree, in her B.K.F Hardoy Chair. Only very few will be able to describe the chair. Far less name the designer(s). And no one bought one on the strength of Miss November's recommendation.

The exhibition still has a few weeks to run and so there is still time to make up your own minds.

Obviously if your not comfortable around lots, as in lots, of images of naked females and women in various stages of undress, your not going to enjoy the exhibition and shouldn't go. Nor should you go if 1960s faux-jazz lounge music makes your stomach turn. A constant background drone diffuses through the exhibition space.

If however you enjoy all that, or at least can contextualise and accept such, Playboy Architecture, 1953-1979 is a thoroughly entertaining and informative exhibition that, as we say, may not prove the students theory but does provide insights that their logic wasn't entirety misplaced and that Playboy was at least partly responsible for advancing, for example, American mid-century modern.

And as we all learnt at school, showing your workings always gets you bonus marks, even if the end result isn't the required one.

Playboy Architecture, 1953-1979 can be viewed at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Schaumainkai 43, 60596 Frankfurt am Main, Germany until Sunday April 20th 2014