"What is the Paris Exposition?", asked Roger Gilman in the September 1925 edition of The Art Bulletin, "It is a new world of the applied arts. It is a new world of reality, reality in the square mass of concrete construction, reality in the smooth surfaces of machine products, reality in wonderful new materials offered by our mastery of science and transport, reality in the severe plainness of our practical age, reality in a marvellous effort to design everything and copy nothing. And it is a new world of color, rich and strange harmonies."

Hyperbolic?

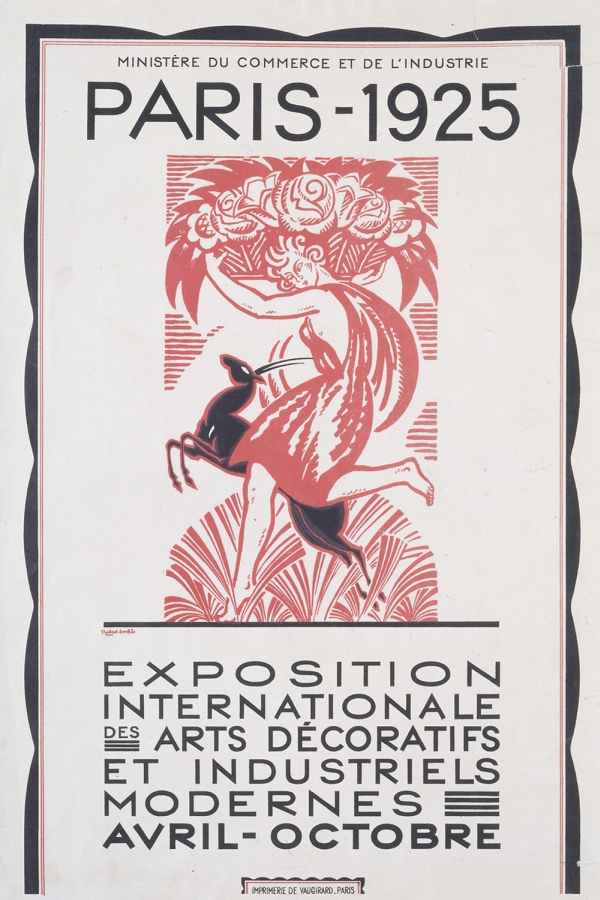

Perhaps, but l'Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes which opened in Paris on April 28th 1925 was without question one of the most important, and for all interesting, fairs of its age.

Originally proposed in 1907 by the French politician and literature critic Charles-Maurice Couyba as an exploration of the question "Why do our merchants and decorators, who are so ingenious in the design and fabrication of single pieces, not take the initiative in a renewal of moderately priced designs for distribution in unlimited numbers of copies?" - so the handwork versus industrial production debate that was dominating central European creativity at that time - it took the various factions until 1912 to find a common position and to propose a fair for 1915. By which time deteriorating relations between France and Germany and the approaching Great War made staging such an event impossible.

By the 1920s Europe had calmed enough to allow the organisation to begin again and in 1922 the organisers confirmed that the fair would finally take place in Paris from April to October 1925.

Although largely a Francophone event the 1925 Paris exposition included pavilions from some 18 nations including Italy, Russia, Poland, the United Kingdom and Austria; and didn't host notable absentees, including Bauhaus and De Stijl. Absentees all the more regrettable given both the word "modernes" in the fair's title and the organisers stipulation that all submitted works must "express a modern inspiration"

The absence of Bauhaus can be put down to the French sending the Germans their invitation so late they had no chance to organise themselves properly, Franco-Germanic relations still not being that good. And whereas Holland did a have a pavilion, according to Marie-Thérèse van Thoor De Stijl's absence was largely on account of Theo van Doesburg's stubbornness. We can't confirm or deny this. But it does sound most intriguing.

It must however also be noted that in addition to the absentees the 1925 exposition did represent an important milestone for several soon-to-be stars of their branches, including Poul Henningsen who was awarded a Gold Medal for what was to become the first in the now legendary PH lamp series, the then student Arne Jacobsen who was awarded a Silver Medal for a chair project, while a fresh faced Gio Ponti was awarded a coveted Grand Prix for a collection of objects for the Florentine porcelain manufacturer Richard Ginori.

Despite the plethora of pavilions, an exhibition concept that took the fair into the department stores and showrooms of the city, the illuminated Eiffel Tower and the almost incomprehensible quantities of marble, ebony, lacquer and tropical hardwood employed by the leading architects and designers of the period for their pavilions and furnishings, the 1925 Paris exposition is principally remembered today for two reasons: the fact that the exposition gave the primary architecture and applied arts movement of the period a name - Art Deco - and the l'Esprit nouveau pavilion from Le Corbusier, a pavilion that was one of only two genuinely modernist pavilions built for the fair - the other being Konstantin Melnikov's Russian pavilion - and an object not without its controversies, controversies which meant that according to Scarlett & Townley, "It was only at the last minute before the opening, by direct intervention from the Minister of Fine Arts, that the hoarding, 6 metres in height, erected by the authorities to conceal the building, was removed." Which doesn't sound especially welcoming. Or modern.

And in terms of the name Art Deco: as Alastair Duncan rightly points out, by the time the phrase was coined the movement was largely over; consequently, one must consider l'Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes as more of a wake for Art Deco than a christening. But of course being an Art Deco wake, and despite the best efforts of Le Corbusier and Konstantin Melnikov, it was a very decadent wake.

And in the words of Roger Gilman "...the most arresting and stimulating sight in Europe this summer"

We're genuinely sorry we missed it!