Not the Situla itself.

But rather what is depicted on that small, delicately carved, 10th century ivory object: the four Christian Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, busy writing their gospels while seated at height-adjustable desks.......

.....or possibly, possibly, height-adjustable desks.

As Bert S. Hall, to whom we will be eternally indebted for introducing us to the Situla,1 notes, the depicted carvings on the poles in the middle of the evangelists' desks could be be functional, but could also be purely decorative; we, and as we will discuss, believe the carvings are functional, that the depicted desks are height-adjustable, and as thus represent one of the earliest references to that most contemporary of office furniture essentials.

But let's start with the Situla.2

Believed to have been created in Milan between 974 and 979 CE at the behest of the city's, then, Archbishop Gotofredo in context of a (possible) planned visit to Milan by the, then, Holy Roman Emperor Otto II, the Situla is today part of the treasures of Milan Cathedral, and depicts in addition to the four Evangelists Mary and the infant Jesus, and that, as Paola Venturelli discusses, in a form that has no apparent antecedent in western iconography.3

What interests us however is less the question of the Situla's antecedents, as the question if the depicted desks are themselves antecedents?

Or better put the depicted lecterns, that antecedent of the contemporary desk.

Whereby the first thing to note is that the depictions are just that, 10th century depictions of scenes believed to have occurred some 900 years earlier, and scenes for which no documentary evidence as to the furniture, utensils, scenography, etc exist. The scenes on the Situla are imagined, fictive, figurative.

And the lecterns? Are they also imagined, fictive, figurative?

We admittedly can find no physical examples of tenth century lecterns matching the depictions on the Situla. But tenth century furniture is generally more plentiful in its absence than presence, or as Eric Mercer opines in terms of medieval furniture, "there are very few pieces which can be certainly ascribed to a date before 1200 and not many to before 1300"4, or as Penelope Eames opines, "before the twelfth century, extant medieval furniture which is complete rather than fragmentary is almost wholly confined to a handful of thrones, the majority of which are of stone or metal".5 Thus it would be a wonder if we could find a physical example.

And so maybe let us approach the subject from another perspective.

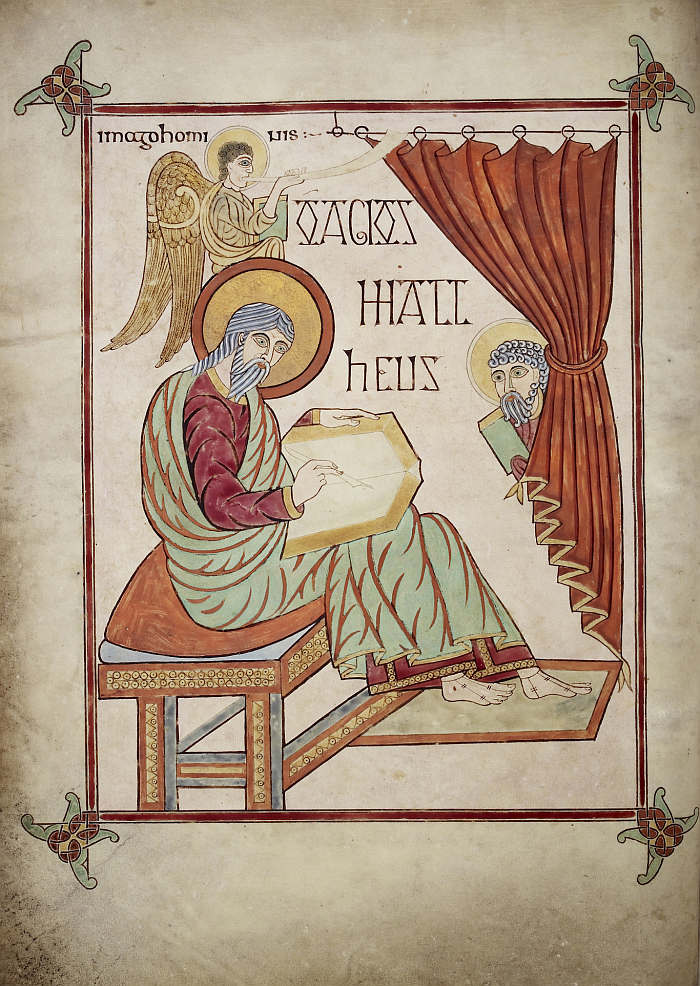

Some of the earliest depictions of the four Evangelists at work on their gospels are to be found in the late 7th/early 8th century Lindisfarne Gospels, a work which depicts three of the four with their manuscripts on their knees, alone Mark has the aid of a round lectern.

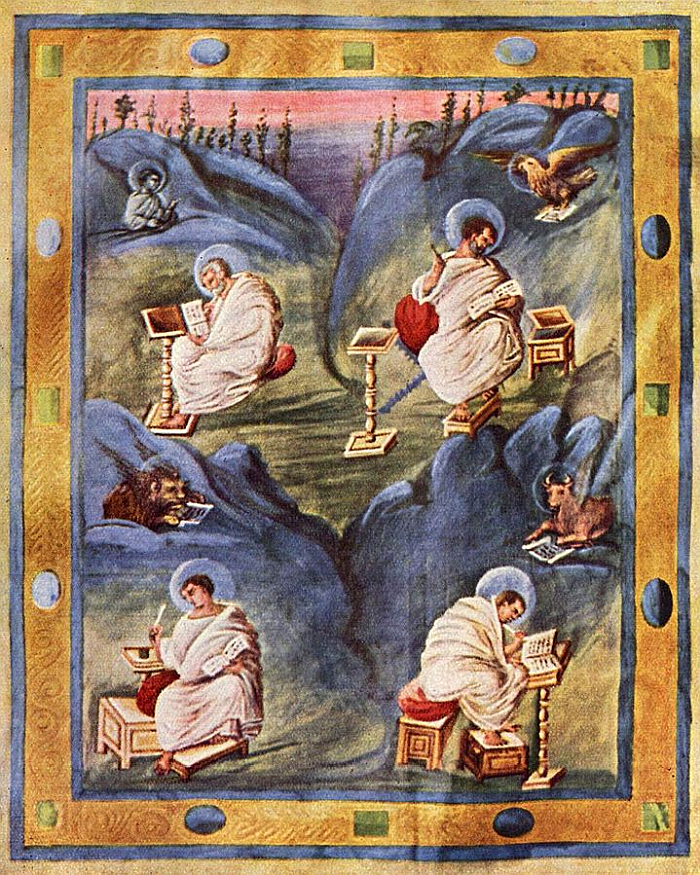

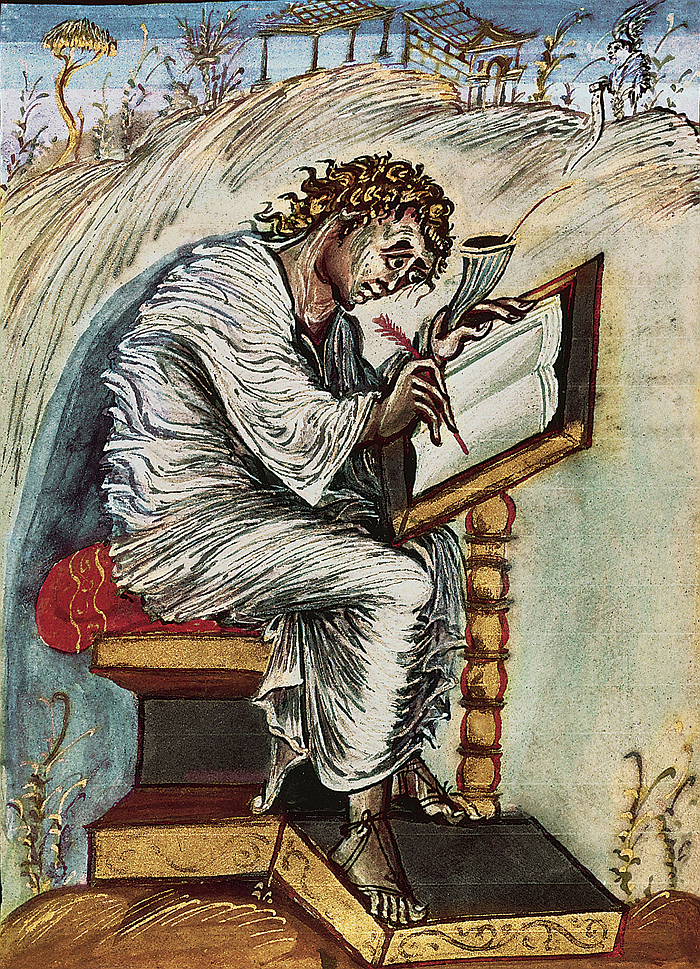

And as Bruce Metzger discusses, from antiquity until the early centuries CE most depictions of scribes at work show them either writing on tablets while standing - wax tablets, but just another perfect reminder that we've not evolved, only technology has - or sitting while writing on scrolls placed across their knees; however, "during the latter part of the eighth century and throughout the ninth century the number of artistic representations of persons writing on desks or tables shows a marked increase."6

And in context of the four Evangelists means in near any text from the early ninth century onwards you will, and generalising to the point of inaccuracy, regularly find two of the four sat at lecterns; for example, and amongst others, the early 9th century Ebbo Gospels associated with the cathedral in Reims sets Matthew and Luke at lecterns, while the Regensburg Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram from ca. 870 CE depicts Luke and Mark working at lecterns. But why not all four? Metzger opines this could be related to a conservative tradition amongst the artists of the period, of an established, conventional, romanticised, tradition of depicting the Evangelists writing with their papers on their laps.7

First with la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo are all four sat at lecterns.8

Such a progression in the depiction of writing habits in the early centuries CE would, logically?, have been influenced and informed by developments in the actual, real, utensils and furniture available for and employed in writing.

Or put another way, an argument can be made, and we will make, which follows that the artists of such medieval iconography would not only have followed existing conventions, would not only followed tradition, however romanticised, but would have incorporated contemporary understandings, would have incorporated contemporary objects into their works. And that possibly subconsciously. An individual living in the ninth or tenth century who had only known monks working at lecterns, arguably, wouldn't question if that had always been so. Would have believed it had always been so. Which isn't to mock previous generations, far from it, but is to acknowledge that over time our understandings of history, as with our understandings of, for example, anatomy, astronomy, geography, furniture, religion, etc have evolved and developed. Or put another way, you try explaining to a five year old that smartphones haven't always existed.

Thus, the argument continues, as lecterns became more popular in reality they, logically?, became popular in iconography.

And continuing that argument, the fact that the vast majority of the lecterns depicted in 9th century iconography are very clearly carved, turned, would tend to indicate that carved, turned, lecterns were a common object in the 9th century. Certainly in those places where monks were to be found.

However, while unquestionably carved, turned, the depicted 9th century lecterns are also unquestionably static, the depicted carving and turning is purely decorative.

And the carving on the Milan Situla?

For us there are a couple of important factors, a couple of important, fundamental, differences, betwixt the lecterns on la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo and the 9th century depictions.

Important, fundamental, differences which, for us, indicate the depicted carving and turning is very functional.

Firstly the la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo lecterns are held within a frame. Throughout the previous two hundred years (more or less) whenever lecterns have been depicted in association with the four Evangelists they have been free-standing, single, turned poles. See above. And below. The poles depicted on la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo are held within a frame. Which is a new form of lectern, a new form of writing furniture. And if we step away from the lectern for a moment, and consider the process of creating the Situla: it's a miniature carving in ivory. And with such you don't take on extra work, but you do want a realistic depiction. And the carving is phenomenal, the carver clearly had an eye for detail and knew how to achieve it, for example the way the front post of the lectern is shorter than the back and thus accommodates the slant of the lectern top isn't something most 10th century artists would have considered. The carver understood their art, but if they could have gotten away with a free-standing single turned pole, we'd argue, they would have. But the carver placed it in a frame. Why?

Or, more accurately put, placed three of the four depictions in frames. While Matthew, Mark and John are busy at lecterns akin to the one illustrated above, Luke's is of a different kind. Luke's is very much a free-standing single turned pole, an object we can sadly find no picture to publish or link to,9 but is very much an object whose carving is unquestionably decorative, is very static. Why? Symbolism? A coded reference to Luke's place in the 10th century church? "An ecumenical matter?" He couldn't afford the other type? Truth be told, we're not that interested; what interests us is the fact that Luke's lectern is different, and that in its difference underscores that the other three have been deliberately placed in a frame. Why?

Secondly, not only is the carved pole held in a frame but it passes through through two braces. And while that could be considered generally useful in aiding stability, it takes on an extra relevance if the pole is a screw. In the 10th century screws were hand-crafted from wood, and regardless of the skill of the individual, you're invariably going to get a bit of give. The double brace helps compensate for any inconsistencies in the horizontal plane, while also providing two points of resistance to help carry the weight of the book, for providing support in the vertical plane. It's the construction you would choose if the carvings on the pole were functional. If one so will, the function defines the form.

But for us the decisive argument in favour of a height-adjustment functionality is the third: the way in which in the depictions of Matthew, Mark and John, the carved pole extends below the lower brace. There is, for example, an 11th century depiction which similarly places a carved pole within a frame; the bottom of that pole is however resting on the lower brace, and thus the brace could be considered to be supporting it. And the pole features a double helix, which not only isn't practical as a screw but would tend imply some symbolic status, a vine or some similar Christian imagery. With la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo we not only have a single helix, but it passes through the lower brace. Again why? That's a lot of extra work, they all end in a point, and is, we'd argue, only necessary, as in both physically necessary in reality and artistically necessary in context of a realistic depiction, if the pole turns.

If the pole turns, the construction is functional, the lectern is height-adjustable.

And, and despite being unable to locate any corroborating evidence, any actual lecterns, we would argue that, and returning to the above position that most tenth century religious artists would have relied on a combination of reference to existing works and contemporary inspiration for their depictions, would have realised a work that not only fitted in with the traditions of Christian iconography but the reality of contemporary society, the lecterns depicted on la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo indicate..... no, no, not indicate...... the lecterns depicted on la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo confirm that the height-adjustable lectern was known in and was used in late 10th century Milan.

Which, yes, is a bit like Einstein's theoretical prediction of the existence of Gravitational Waves without him offering supporting evidence10; but we're equally confident that some day, somebody will find that evidence.

If the lecterns on la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo are height adjustable, its does pose the question of who first proposed such? And where? Why?

The screw had been known since Roman days and was used, for example, in presses for olive oil and wine, devices which by necessity rise and fall. Thus it's a fairly short step to a lectern which rises and falls. Yet, and as so oft, someone has to identify the necessity of a lectern that rises and falls. And that isn't so simple.

And is a who, where and why, that involves quite a bit of conjecture and postulation. And a little fantasy and imagination.

When one views 8th, 9th, 10th century Christian iconography, one notices not only a development in how the Evangelists wrote, but the construction of the furniture they used, and for all that whereas, and generalising dangerously, in works such as the Aachen Gospels or the Codex Aureus of Lorsch, the seat, footstool and lectern are all depicted as individual objects, in a work such as the Ebbo Gospels or the Gospels of François II, Matthew, and accepting that 9th century artists didn't do perspective, appears to be sitting at a single unit, a single object featuring seat, footrest and, fixed in a corner, the lectern.

Similarly on la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo all four lecterns, including Luke's static lectern, appear to be mounted on the structure on which the Evangelists are sitting; that seat and lectern are fixed to a small raised platform, a workstation. And thus, possibly, indicating a move from the use of mobile objects for writing to static, in-built, constructions and, potentially, therefore a greater institutionalisation of the scribe's profession. In addition such constructions, if they existed, could be considered as not just a potential forerunner of the contemporary single workstation, but, potentially, of the church pew and/or single unit school bench/desk.

And thus one could, and again, we will, build an otherwise unfounded argument, that scribes being invariably of different sizes, in some Scriptorium or other in the course of the 9th or 10th century the idea was hit upon to make the lecterns height-adjustable as a response to the differing statures of the monks, and in order to thus aid the work of the individual. And to enable hot-desking in the newly in-built, institutionalised, workspace. The technology to achieve such was known. The step was short. Just had to be identified. While such a set up also allows the lectern tops to turn, to be positioned at a freely selectable angle, and thus allow the scribe not only to sit at a relation to the lectern that was appropriate for them and/or the task at hand, but also to adjust that position in response to, for example, changing light conditions. Such a theory does of course rely on the transposing of contemporary understandings on historic understandings, which is rarely a good idea. But which is very tempting. And if true would be a further demonstration that functionalism isn't a 20th century concept.

Evidence we have none. But somehow in course of the 9th or 10th century lecterns, so our argument, were fitted with a functionally rather than decoratively carved supporting pole, with a screw, and became height-adjustable. Had they not, la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo would depict all four sitting at lecterns similar to Luke's.

We are admittedly leaning quite a bit further out the window here than we are normally comfortable with; if that's because we feel unconquerable in our position, or because we really, really want the Situla lecterns to be height adjustable, and fear part of our soul may wither and be lost to us forever, and with it part of our joy in life, if they aren't, isn't clear. We suspect the latter, hope the former.

And certainly feel emboldened in the justification inherent in the former through developments that came after the creation of la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo.

Or at least would come by the 15th century.

We can, again, find little, no, evidence of the height-adjustable lectern, or indeed any screw/spindle height-adjustable furniture, in the 11th, 12th or 13th centuries, but as above, that shouldn't surprise us. And that we can find no evidence doesn't mean that evidence doesn't exist. There's a fine but fundamental difference between no evidence and no known evidence, and we may just be looking in the wrong places. In the wrong manuscripts. In the wrong museums. Nor can we read the Latin and Aramaic that would be necessary to spot a fleeting reference to height-adjustable furniture. Nor have we access to all relevant sources, many of those that aren't online are locked away in vaults in countries we're currently unable to visit. Nor do we have the year and a bit it would take for a full survey, we've had to abbreviate our search.

Or maybe height-adjustable lecterns just didn't catch on; maybe contemporary understandings were too conservative; maybe the ruling taste rejected such a technological gimmick; maybe suitable skilled craftsfolk were rare; maybe they were too expensive; maybe it was a slow burner, like tubular steel seating which for all its popularity today wasn't particularly so in the 1920s and 30s, or the Centripetal Spring Chair which was developed in the late 1840s, vanished in the late 1850s and reappeared 140ish years later as the multi-functional office chair. Furniture design, relationships to furniture, evolves relatively slowly. And while four hundred years would be a really long, slow, burn even by furniture's standards, in the fourteenth century we do find a possible (re)appearance of the height-adjustable desk.

Possibly.

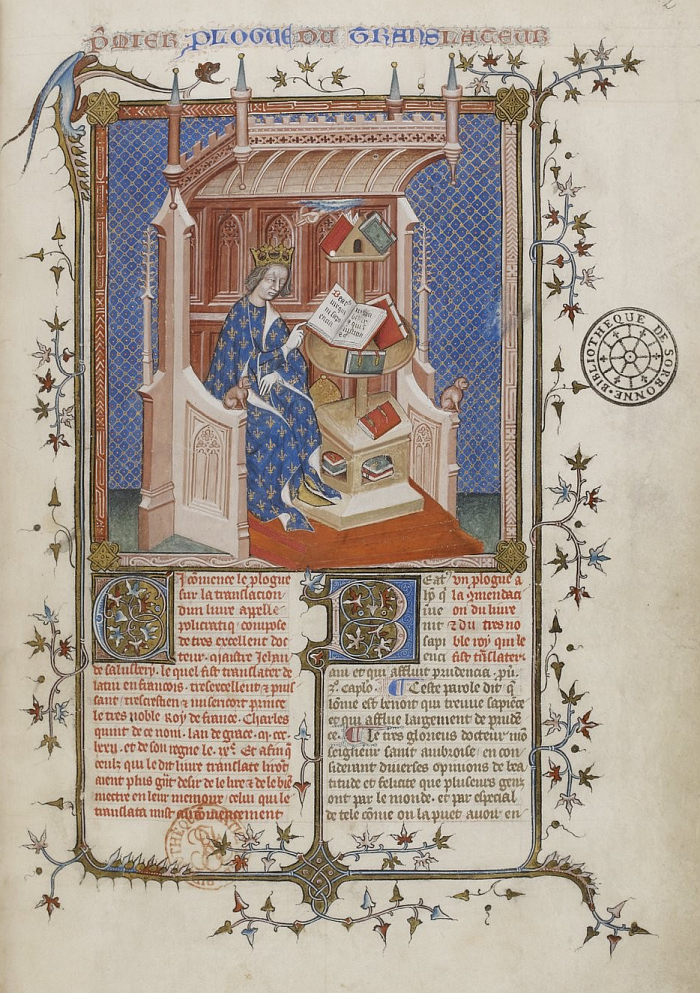

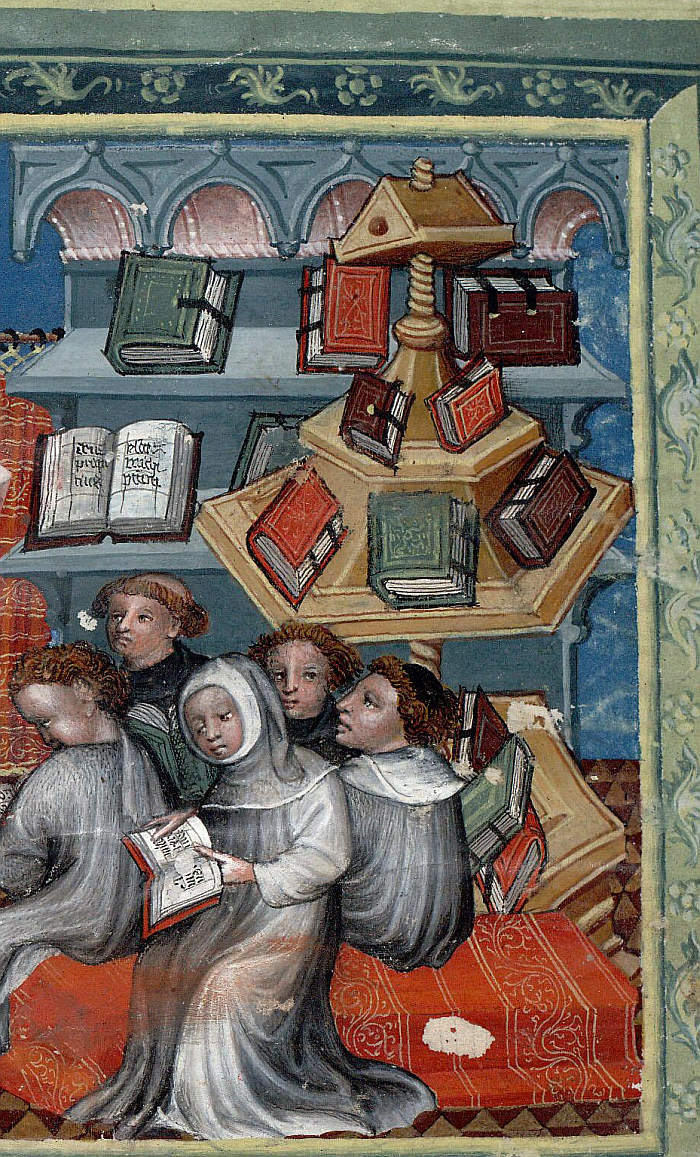

J. W. Clark notes that between 1364 and 1368 the library of Charles V was moved from the Palais de la Cité to the Louvre, and that this library contained "revolving desks".11 Exactly what they were isn't recorded, J. W. Clark however postulates they could have been similar to what Percy Macquoid and Ralph Edwards, refer to as a "Wheel Desk",12 an object depicted in a late 15th century edition of Boccaccio's Des Cas des nobles hommes et femmes, and which shows Boccaccio and Petrarch at an octagonal? desk that clearly rises and falls on a central spindle13, and which could be considered as an adaptation of the revolving, but not height adjustable, 6th century Buddhist octagonal bookcases mentioned in our Radio smow Bookcase Playlist. The depiction of Boccaccio sitting and Petrarch standing beautifully illustrating, when perhaps unintentionally, the sit-to-stand functionality of such an object. While the fact that both are doing that "straight back at you", finger gun thing is particularly joyous.

If Charles V had such an object a century earlier is unclear; however, a 1372 illumination by Jean de Salisbury, see above, depicts Charles V in said Louvre library sat next to an object that features book storage in the base, a standing height lectern and in the middle a round table that may or may not rotate. And if that object is, as we believe it is, the object referred to by Clark, and it certainly features the bancs and roes - boxes and wheels - Clark refers to, then the table would be a carousel. But not to judge from Jean de Salisbury's image, height adjustable.

Unlike two very similar objects from the early 15th century.

One, depicted in a copy of Boccaccio's De casibus virorum illustrium from 1420 held by Oxford's Bodleian library and which obviously is a height-adjustable book carousel, and thus both a height-adjustable desk and a height-adjustable side table. Another genre in urgent need of re-discovery. And again there's that "straight back at you", finger gun thing, this time in the direction of Adam and Eve. Which is a confident statement. And would tend to underscore that finger guns were very much à la mode in the 15th century.

Two, depicted, see below, in Petrus Comestor's Bible historiale from ca. 1415-1420 and in which not only is the standing height lectern height adjustable, but the spindle on which it is mounted goes all the way to the base, meaning the hexagonal? carousel is also height adjustable, is a height-adjustable desk. Disappointingly though no finger guns, which does cause us to question if we weren't a little rash in pronouncing their 15th century popularity....

And one could argue that an object depicted in the first decades of the 1400s would have been known in last decades of the 1300s, and thus that the height-adjustable book carousel/side table/desk was known in the late 14th century. And that Charles V's might have been height-adjustable, but just not so clearly depicted as such.

And then in the 15th century we, finally, find physical evidence of height adjustable lecterns.14 Or almost physical evidence: the MAK Vienna has in its photo collection a 19th century image of a 15th century height adjustable lectern from a church in Herrieden, near Nürnberg, a much more ornate work that than that on the Milan Situla, but which features the same double bracing and is in many regards a free-standing version of the integrated Situla lectern; similarly the Antiquities Museum of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina in Alexandria posses in their collection a late sixteenth century lectern which not only features the double bracing, but also the storage boxes from Charles V's library.

By the late Middle Ages height adjustment via a screw/spindle was practised in lecterns and other furniture objects that can be considered predecessors of contemporary desks. Such a concept must have arisen somewhere. Why not 10th century Milan?15

Which yes, once again, is a very Christian and very Eurocentric understanding. We have searched for an alternative (hi)story in other continents and cultures, without success. That may however be more to do with our (lacking) competencies in such matters rather than the actual truth. And we would be genuinely delighted if an alternative (hi)story could be proven. Remain convinced however that wherever the idea came from, and whomever first identified the necessity and developed a solution, the height-adjustable lectern was known and was used in 10th century Milan.

Before that knowledge and understanding became lost.

Victorian height-adjustable desks are rarer than Medieval, even amongst American patent furniture, and that despite, as previously noted, the benefits of moving while seated being known in the mid-19th century, and thus, arguably, the benefits of sit-to-stand desk solutions; unless we're missing something very obvious height-adjustable desks weren't a subject the inter-War functionalists concerned themselves overly with, and that despite the scores of architects and designers amongst their number who could have benefited from such, and being a near textbook example of a functional solution; the earliest height-adjustable desk patent we can locate is from 195616, and in his 1970 text which introduced us to la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo Bert S. Hall only speaks of them being an antecedent of the revolving bookcase, height-adjustable desks clearly weren't an issue in late 1960s Los Angeles. Only in the 21st century has interest in the height-adjustable desk really blossomed.

Despite having been known since the 10th century.

And yes there is something absolutely delicious in the possibility of a genuine milestone of office furniture design, such a simple, logical, functional solution to a complex problem, an answer we've had to develop in the 21st century, existing quietly all these centuries in Milan, that centre of the Italian furniture industry, that centre of Italian furniture design, the home of Salone del Mobile, and once a year the holiday home of the international furniture industry and international furniture design.

1Bert S. Hall, A Revolving Bookcase by Agostino Ramelli, Technology and Culture, Vol. 11, No. 3, July 1970, footnote 8, page 391-392

2For more photos and descriptions see https://www.restituzioni.com/opere/situla-di-gotofredo/ (accessed 07.09.2020)

3Paola Venturelli, La situla eburnea di Gotofredo del Duomo di Milano: segnalazione di quattro copie accessible via http://www1.unipa.it/oadi/oadiriv/?page_id=767 (accessed 07.09.2020)

4Eric Mercer, Furniture 700 - 1700, Weidenfeld, Nicolson, London, 1969

5Penelope Eames, Furniture in England, France and the Netherlands from the twelfth to the fifteenth century, Furniture History Society, London, 1977

6Bruce M. Metzger, When did scribes begin to use writing desks, in Bruce M. Metzger, Historical and Literary Studies. Pagan, Jewish and Christian, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1968. In addition one must add that the move wasn't purely towards lecterns, but also, for example, knee boards, see, for example, Mark as depicted in the Quattuor Evangelia ca. 791-810 CE, note also the ink stand is atop a turned pole.

7ibid

8This is a big claim. And not one we're certain we can substantiate. For all given our general ignorance of early medieval iconography. But we're going with it. And expect to be proved wrong. And would also note that in the Gospels of François II from 850-875 three of the four are sat at lecterns, John is writing on his lap, but a lectern is standing next to him.

9There is an image in Paola Venturelli's above quoted article, but it isn't that clear, while at https://www.restituzioni.com/opere/situla-di-gotofredo/ there is an image of Luke illuminated from within which allows the form to be understood when not fully seen. The best images we know of are in Rossana Bossaglia and Mia Cinotti [Eds.], Tesoro e Museo del Duomo. Volume 1 Antiquarium: tesoro e arti suntuarie, Museo del Duomo, Milan 1978 Plates 88 - 91

10It's not, obviously. Apologies. For all to Albert Einstein.

11J. W. Clark, Libraries in the Medieval and Renaissance Periods. The Rede Lecture delivered June 13th 1894, Macmillan and Boews, Cambridge, 1894

12Percy Macquoid and Ralph Edwards, The Dictionary Of English Furniture. From the Middle Ages to the late Georgian period. Vol.II (Ch. - M.), Country Life, London, 1924 Page 209ff.

13Here again, that both Boccaccio and Petrarch died in the 1370s tends to imply that they are illustrated at an object known to the illustrator but not necessarily known to Boccaccio and Petrarch. Although it may have been.

14In addition to the screw based lectern, Jacob von Falke also depicts a 15th century lectern that was displayed in context of an exhibition of Middle Ages wooden furniture held at the, then, Österreichischen Museum Vienna in winter 1892/1893, and which is height-adjustable via a "peg and hole" system and which appears to have two positions, see Jacob von Falke, Mittelalterliches Holzmobiliar, Verlag von Anton Schroll & Co. Wien, 1894 Plate XXXVII

15The more we've been developing this post, the more an alternative, darker, position has arisen. La Situla del vescovo Gotofredo is recorded as being in the Duomo since 1400. And before? Although believed to have been in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio where Gotofredo was based before becoming Archbishop of Milan in 974, as Mia Cinotti notes, "a quick glimpse of the S.Ambrogio archives revealed no trace of either its ancient presence or its transfer to the Duomo", see Rossana Bossaglia and Mia Cinotti [Eds.], Tesoro e Museo del Duomo. Volume 1 Antiquarium: tesoro e arti suntuarie, Museo del Duoma, Milan 1978. We don't want to cast doubt on its provenance, not least because that really would cause part of our soul to wither, and as far as we are aware no one else is casting doubt; but given how far ahead of its time it appears to be, could it also be more recent than 10th century? Could the lecterns be the evidence for that? That they, possibly, simply couldn't have existed in that form in the tenth century and thus confirm a more recent creation of the Situla? That it's less a case of the Situla confirming the lecterns existed in the 10th century, as the lecterns confirming the Situla didn't exist in the 10th century? We do hope not, that would be awful, but the thought simply won't leave us.........

16Patent CH316117, Höhenverstellbarer Pulttisch, Willy Baumann, Kriens. Granted 30. September 1956. Available at https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/004496249/publication/CH316117A?q=CH316117A (accessed 07.09.2020)

But then, la Situla del vescovo Gotofredo is housed in the Duomo, and not in those more profane cathedrals of Milano where furniture designers tend to congregate, celebrate and take the communal wine......