#officetour Milestones – Centripetal Spring Chair by Thomas E. Warren

While understandings of form, of beauty, in context of the objects with which we surround ourselves continually evolve and develop, understandings of function are, generally, much more stable. Or at least are once they have been identified, understood and normalised.

Something that can be studied and appreciated in Thomas E. Warren’s Centripetal Spring Chair…..

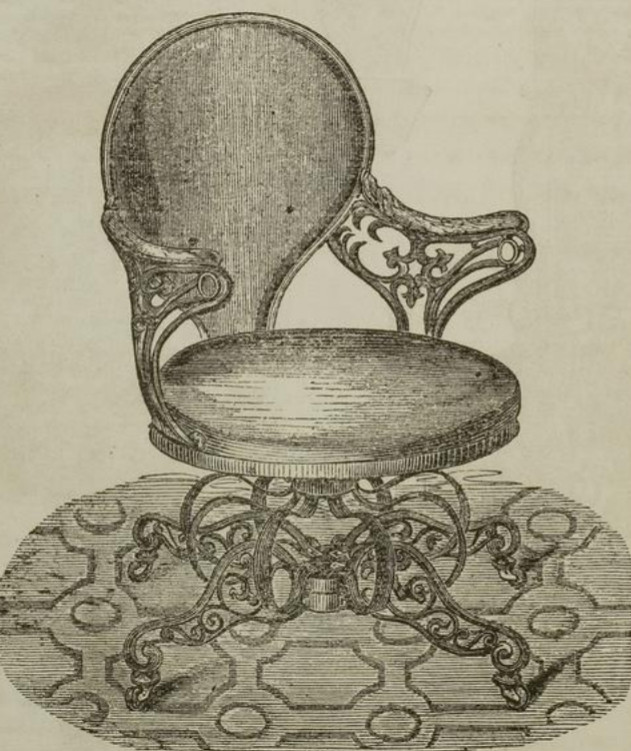

A Centripetal Spring Chair by Thomas E. Warren for the American Chair Company with tapered back and armrests (Image © and courtesy Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn)

We once saw a cartoon, which we sadly can no longer locate, of two Victorian gentleman standing next to a small steam locomotive on which was mounted a candlestick telephone, a gramophone and a large bellows camera; and one gentleman asking the other, who needed a portable telephone which could play music and take photos…….?

We think something similar when looking at Thomas E. Warren’s Centripetal Spring Chair: who needs an office chair which not only features a revolving seat, but which also allows free movement forwards, backwards, sideways and in circles…….?

In 1849 the answer was as many as who needed a portable telephone which could play music and take photos, and thus the Centripetal Spring Chair was a relatively short-lived excurse in 19th century American furniture design.

The basic concept inherent within the Centripetal Spring Chair, the functionality inherent within the Centripetal Spring Chair, remained, and would be widely taken up, expanded upon, and normalised a century and a bit later.

Albeit in a very different technical expression.

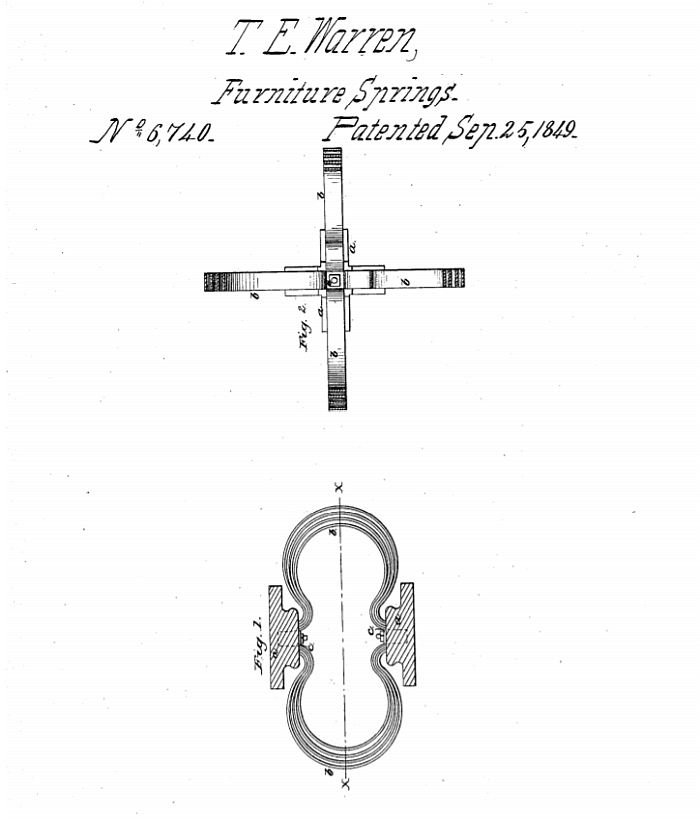

The heart of the Centripetal Spring Chair is a C-shaped steel spring patented by Thomas E. Warren in 1849 and which, and as he describes in the patent application, doesn’t straighten, elongate, under pressure as with the common elliptic springs of the period, but rather rolls, closes, from a C to an O, and which thereby, so Warren, not only makes his springs stronger than conventional elliptic springs, but allows them to “bear the weight with which they may be loaded more steadily, without what is termed throwing it off by means of sudden jolts”1

Springs which when judiciously placed between a chair base and seat allow for a simple, controllable, rocking motion in all directions; springs which facilitate “postural changes by using the sitter’s feet as a fulcrum”2; springs which allow the chair to move, flow, naturally with the occupant, as if an extension of the human body.

And springs which Thomas E. Warren attached to all manner of chairs, or perhaps more accurately put, attached to chairs which could be used for all manner of activities, the differentiation of chair typologies being somewhat less advanced in 1849 than today. And thus despite the oft claimed status of the Centripetal Spring Chair as the first multi-functional office chair, it wasn’t really; much more it is and was one of the first objects to feature and exploit a multi-functionality that would become popular in office chairs, in office seating.

Which isn’t to say it wasn’t intended for use in offices, it very much was, amongst the myriad uses mentioned in any given Centripetal Spring Chair advert one invariably finds “office”. Whereby one must remember that the office, certainly the large commercial office, was still in its (relative) infancy in the mid-19th century and thus while Warren was invariably hoping to place his chairs in larger spaces, an, arguably, more probable office was the home office, the study. Although one must also note that before developing his Centripetal Spring Chairs, and establishing the not unconfidently named American Chair Company to produce and distribute them, Warren worked variously as a clerk, broker and merchant, and so would have had personal experience of small commercial offices.3 And the, invariable, shortcomings of the contemporary small commercial office chairs. While, and not uninterestingly, Warren also seems to have briefly worked as a music teacher, which links in nicely with another much promoted, and seemingly obvious, use of the Warren spring as a component of a music/piano chair/stool.4

A Centripetal Spring Chair by Thomas E. Warren for the American Chair Company with tapered backrest and no armrests (Image © and courtesy Wolfsonian–FIU, Miami)

Aside from the springs the other three central features of the Centripetal Spring Chair were and are the cast iron frame, the upholstery and the prominent ornamentation.

The former, no doubt, inspired/informed on the one hand by the large iron industry that existed at that period in and around Troy, New York, where Thomas E. Warren and his American Chair Company were based, and on the other by the rise in the use of iron as an alternative to wood in furniture construction that occurred in the course of the 19th century, a rise, arguably, driven by (a) the fact that iron, in contrast to wood, doesn’t burn, (b) on iron’s ready, free, castability, and thus its advantages over wood in terms of both the forms it could achieve and the industrialisation of the production of those forms, and (c) that in the 19th century iron was considered modern and contemporary, represented, if one so will, progress. If not a progress all were approving of; an 1851 advert for the N. Y. Patent Merchandise Co. who sold Warren’s chairs, considered it necessary to argue against the “erroneous idea prevalent in this country that Iron Furniture must necessarily be coarse and clumsy, and inapplicable for household purposes”.5 A situation which neatly predicts the rejection amongst a percentage of the population of the bent tubular steel of the inter-War Modernists on account of its perceived coldness and impersonality; metal furniture, it would appear, has always had it tough. And has never replaced wooden furniture.

Yet whereas the inter-War Modernists compounded their use of metal by denuding their works of of all upholstery, Warren not only adorned his chairs in rich velvet, an act, one imagines, intended to guard against any accusations of coarseness or clumsiness, but also prudently hid the spring mechanism behind a valance; the brutality of the spring construction arguably being too much for Victorian sensibilities and needed to be discretely obscured.

And equally prudently made use of that form of iron that was very much approved off in the mid-19th century: ornamental cast iron. As Ellen Marie Snyder neatly describes,6 the process of producing ornamental cast iron became particularly refined in the course of the 1800s, initially in the United Kingdom, subsequently in the United States, and with the increasingly refined process, increasingly refined works could be realised, works that became themselves the height of refinement, or as The Art-Union deliciously opined in 1845, “the most stubborn portion of the mineral kingdom has been annexed to the realms of taste”.7 And was accordingly used with gusto and wherever one could, and thus, unsurprisingly, features prominently in all versions of the Centripetal Spring Chair.

A Centripetal Spring Chair by Thomas E. Warren for the American Chair Company as depicted in The Illustrated Exhibitor, 1851

A further reflection of the formal, aesthetic, understandings of the period can be studied in the artwork that was, as far as we can ascertain, regularly applied to the backs of Warren’s chairs, and that often as period conform romanticised artwork. Or as The Boston Olive Branch noted in 1851 of a Centripetal Spring Chair in the possession of Thomas Whittemore, editor of The Trumpet and Universalist, “upon the back is a neatly executed painting of the Hoosac tunnel, completed, and a train of cars about to enter from the east. In the distance is a beautiful sketch representing a body of water with steamers and pleasure boats pling to and fro, and uplands and hills rising in the back ground.”8 All very idyllic. But that this was a heavily romanticised idyll can be understood by the fact that although in 1851 the Hoosac tunnel was being discussed, construction didn’t start until 1855. And wasn’t completed until 1875.

In addition to romanticised art Warren’s Centripetal Spring Chairs are often encountered with lacquered backs; as oft discussed in these dispatches, following Japan’s ending of its self-enforced isolation in the mid-19th century oriental lacquer work, or more commonly local adaptations of oriental lacquer, became very popular in Europe and America and was employed on and with a myriad of goods.

Thus formally, aesthetically, but also materially, the Centripetal Spring Chair was very much a work of its age, was a thoroughly contemporary mid-19th century object.

Similarly in terms of its functionality: the Centripetal Spring Chair stands as a near textbook example of so-called American Patent Furniture, so-called because it was furniture which contained a patented mechanical novelty, a genre of furniture that reached its zenith in the second half of the 19th century and which, as Sigfried Giedion opines, was a moment in the (hi)story of furniture chiefly concerned with motion, “the Americans of about 1850 to 1893”, he notes, “drew upon an almost inexhaustible fantasy to solve the motion problem for furniture”, adding that “no other period knew this mobility, this adjustability to the body”, and that Patent Furniture allowed for “comfort actively wrested by adaptation to the body, as against comfort passively derived from sinking back into cushions”.9 Or if one so will a reimagining of not just furniture, furniture construction and furniture’s function, but our relationship(s) with furniture.

And that not out of idle curiosity or an abstract whim, but because, as Jennifer Pynt and Joy Higgs note, “the design principles underlying multipostural patented chairs accorded with medical concepts of healthy sitting and seating at the time.”10

Ergonomics may or may not have existed in 1850, but medical opinion was that sitting rigid and still wasn’t that good for you. And that movement while seated, multipostural seating, was good for you.

Thomas E. Warren’s Centripetal Spring Chair was one of the very first to, as it were, actively, address the issue of active sitting.

The painted back of a Centripetal Spring Chair by Thomas E. Warren for the American Chair Company (Image © and courtesy Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn)

One of the earliest recorded public appearances of the Centripetal Spring Chair was at the 1849 Rensselaer County Cattle Show and Fair held in Troy, an event that opened on September 25th 1849,11 and thus the very day on which Thomas E. Warren was granted his patent; and newly patented Centripetal Spring Chairs which caught the eyes of the Troy Daily Post who noted “Mr. Thos. E. Warren’s Patent Spring Chairs were decidedly the greatest novelties on exhibition. They are unsurpassed in ease, durability and convenience. They are not on a luxury but a necessity as every body must have one of these chairs.”12 And also caught the eyes of the judges, as Diane Mary Shewchuk notes,13 Warren was awarded a diploma, and $3.00 prize money, for four office chairs and a piano stool. Which may not sound like much, but was more than he achieved a month later at the Great Fair of the American Institute, an event staged at Castle Garden, New York, and where, and to judge by the near endless list of exhibits that were awarded prizes,14 Warren’s chair must have been about the only exhibit not awarded a prize. Not that it went unnoticed, Scientific American singling it out, describing it à la Bill and Ted as “a most excellent invention”, and noting it was “generally admired” by show goers.15

And a positive mention that Thomas E Warren, presumably, noticed because in November 1850 Scientific American announced, in context of an, allegedly, unplanned, visit to the American Chair Company’s factory in Troy that “we have had two of Mr. Warren’s patent spring chairs in our office for the past year, and we are better pleased with them than with any other chairs we have ever seen or used.”16

Then as now little is better guaranteed to get you positive media coverage than a freebie or two.

Something that was clearly well understood at that time: the aforementioned Centripetal Spring Chair in the possession of Thomas Whittemore was also a gift of Warren’s, one caustically remarked upon by the editors of The Carpet-Bag, one of America’s first humour magazines, who bemoaning and lamenting the near complete absence of chairs of any sort in their office, wondered if the American Chair Company would also gift them one, “according to custom”, they confirmed, “we should undoubtedly make some very eloquent remarks on taking the chair.17

That they subsequently didn’t, tending to imply their request fell on deaf ears.

Warren however didn’t rely on PR alone to market his product, and whereas his Centripetal Spring Chairs first public outings may have been at what were, essentially, local agricultural shows, in 1851 he went global, presenting his chairs at the Great Exhibition in London, that first World’s Fair, an event that was to be so influential in the development of understandings in the later 19th century, and an event Warren, presumably, hoped would be influential in the development of his business: ahead of the event he took the precaution of acquiring a UK patent,18 while a Centripetal Spring Chair is illustrated in the official catalogue, Warren presumably paying (handsomely) for the privilege.

However, despite his best laid plans,19 the 1851 exhibition didn’t bring the hoped for international breakthrough; not that Warren’s chairs went unnoticed, one finds occasional reference to them in the press of the period, including in the The Art Journal who in praising the form and function noted that “we have never tested a more easy and commodious article of household furniture”.20

Call us cynical, but the question arises if they also had one in their office?

Yet despite Thomas E. Warren’s extensive, international, PR and marketing campaign, the apparent, and understood, benefits of such a chair to the health and well-being of one sitting in it, the ornate cast iron and plush velvet upholstery, and the prominence of Patent Furniture in America throughout the later part of the 19th century, by the 1860s the American Chair Company and Thomas E. Warren’s Centripetal Spring Chair had vanished.

How? Why?

The Centripetal Spring Chair by Thomas E. Warren for the American Chair Company as depicted in the catalogue to the 1851 Great Exhibition in London

Questions whose answers are neigh on impossible to fully approach because as Diane Mary Shewchuk neatly documents21 there is next to no archival information on the American Chair Company, and only sporadic information on Thomas E. Warren. Or put another way, we are in possession today of more Centripetal Spring Chairs, than information on the Centripetal Spring Chair.

Questions whose answers may or may not involve a mix of the precarious financing and unstable business structures on which the American Chair Company may have been built22; the political and economic situation as America moved ever more inescapably towards Civil War; and/or the sheer number of patent seating objects of the period and thus the very real competition in a still developing market.

And questions whose answers invariably involve the prevailing attitudes of the period, a period which, and once again pre-empting the discussions of the early 20th century, found itself involved in a debate on the merits of industrial production versus craft production in terms of furniture, and also involved in a debate on posture. Amongst the many conflicts of Victorian society one of the most interesting is Comfort versus Elegance: patent furniture may have seen “comfort actively wrested by adaptation to the body, as against comfort passively derived from sinking back into cushions”, but was that elegant? Was that compatible with what Jennifer Pynt and Joy Higgs refer to as “the socio-cultural mores of etiquette and aesthetics”.23 Did one move in one’s chair? In the mid-19th century the ruling taste was the opinion one didn’t, certainly not in public, in private, as with so much in (Victorian) life, different standards prevailed, but in public one sat still. One sat upright. And on a handcrafted upholstered wooden chair. And not on a Centripetal Spring Chair. A work that, therefore, can, must?, be considered a prime example of the right solution at the wrong time, a work that while it invariably had supporters, had not enough to sustain it.

Yet, while the exact hows, whys and wherefores may be uncertain, certain is that from around 1855 Thomas E. Warren’s Centripetal Spring Chair slipped quietly from view……..

A Centripetal Spring Chair by Thomas E. Warren for the American Chair with armrests and a quadratic backrest (Image © and courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

….before reappearing a century and a bit later, or more accurately, the basic concept inherent within the Centripetal Spring Chair, the functionality inherent within the Centripetal Spring Chair reappeared a century and a bit later, not only in works such as the ON office chair by wiege for Wilkhahn, but in all manner of soft ergonomic office seating solutions which promote, via a variety of means, the multipostural seating once enabled by Thomas E. Warren and which considered together, as a single genre, mean that the early 21st century knows more motion in seating than Giedion claimed for the late-19th century.

And a situation that for us neatly echoes the words of Sir Henry Cole, one of the leading figures behind the 1851 Great Exhibition, who opined that the American industrial objects presented in London “adapted to new wants and infant periods of society.”24 In terms of active seating it took society a bit of time to mature enough to fully understand and normalise those wants.

In addition to being a forerunner of the contemporary office chair in terms of functionality, the Centripetal Spring Chair was also a forerunner in terms of manufacturers obsession with offering office chairs in a range of versions: an 1851 advert noting that it was available in “100 varieties, at prices varying from $7 to $75”.25 A variety which can be understood today by the fact that you will rarely, if ever, see two identical Centripetal Spring Chairs; a variety that was achieved not just through varying forms, including with and without armrests, with a choice of backrest shapes, and a range of fabrics, but variations in the ornamental iron work, of making use of developments in ornamental iron casting to develop different decoration for every chair. And a variety of forms and prices the contemporary office chair industry is loath to relinquish: the principle boast for any new office chair being in how many millions of variations it is available. Regardless of how convenient, or otherwise, that may be.

And was also, in many regards, a forerunner in terms of formal considerations on office chairs. For all that the Centripetal Spring Chair stands formally of and for the mid-19th century, it, and generalising to the point of inaccuracy, also formally moves away from much of the conventions of the period. For all the version with the formed, lightly curved, tapering back, a formal, and construction, decision which, for us goes new ways for upholstered furniture, is a much more informal, open, construction, one which differentiates the Centripetal Spring Chair from other seating objects and thus one that, we’d argue, predicts not only the relevance, the importance, of the shape of an office chair to its functionality, but the contemporary formal separation of office chairs from all other chair genres. And a differentiation which may also have alienated it from its intended market, but which today has a certain logic and not unaffecting charm, for all that it is of and for the mid-19th century, it is also, we’d argue of and for today.

And extened considerations which help underscore that while Thomas E. Warren’s Centripetal Spring Chair may not have been an office chair per se, it stands in formal, functional and mercantile contexts as an important milestone in the (hi)story of office chair design………

1.US Patent 6,740 granted on September 25th 1849

2.Jennifer Pynt and Joy Higgs, Nineteenth-Century Patent Seating: Too Comfortable to Be Moral?, Journal of Design History, Autumn, 2008, Vol. 21, No. 3 pages 277-288

3.see Diane Mary Shewchuk, Thomas E. Warren, the American Chair Company and the Centripetal Spring Chair, MA Thesis, S.U.N.Y. Fashion Institute of Technology, February 1993

4. Another obvious and oft promoted use is/was in railway carriage seating. Here the springs are placed pointing forward and backward so that motion would be more up/down and forward/back than sideways. In addition Thomas E. Warren invented a sprung iron backrest for railway carriage seating (US patent 7,539 30.07.1850) and iron carriages (US Patent 10,142 October 18th 1853)

5.Christian Review, October 1st 1851, page xi

6. Ellen Marie Snyder, Victory over nature: the elevation and domestication of Victorian cast iron seating furniture, MA Thesis, University of Delaware (Winterthur Program), August 1984

7.The Mercantile Value of the Fine Arts, The Art-Union, July 1st 1845, page 223

8.Weekly Editorial Memoranda, The Boston Olive Branch, July 19th 1851, page 2

9. Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization takes command. A contribution to an anonymous history, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2013, page 390

10. Jennifer Pynt and Joy Higgs, Nineteenth-Century Patent Seating: Too Comfortable to Be Moral?, Journal of Design History, Autumn, 2008, Vol. 21, No. 3 pages 277-288

11. Daily Albany Argus. September 26th 1849 quoted at https://lansingburghhistoricalsociety.org/parks/rensselaer-county-agricultural-society-fairgrounds/ (accessed 24.07.2020)

12.Troy Daily Post, 30 September 1849 quoted in Diane Mary Shewchuk, Thomas E. Warren, the American Chair Company and the Centripetal Spring Chair, MA Thesis, S.U.N.Y. Fashion Institute of Technology, February 1993

14.see Eigth Annual Report of the American Institute of the City of New-York, February 26th 1850

15. Great Fair of the American Institute. No. 3, Scientific American, October 27th 1849 page 45

16. American Chair Manufacturing Company. Scientific American, Vol. 6, No. 10, 23.11.1850, p. 77 The authors claim that, in Troy for an unspecified reason, they were wandering aimlessly around “to see what we might see,” when all at once, and unexpectedly, they came across Warren’s factory. Yeah. That’s what happened. Yet despite the very obvious PR tone of the text, it is the only known insight into the American Chair Company.

17. An Editorial Chair, Carpet-Bag, August 2nd 1851, page 5

18. UK Patent 13,361 November 21st 1850. Granted not to Warren but John James Greenhough, and not for the springs per se but, for “Improvements in the construction of chairs, couches and seats; parts of which improvements are also applicable to various purposes where springs for supporting heavy bodies and resisting sudden and continuos pressures are required” see Patents for Inventions: Abridgements of Specifications Relating to Furniture and Upholstery 1620-1866, Patent Office, London, 1869, page 155 John James Greenhough was a New York based engineer and patent attorney closely linked with Warren, see Shewchuk for more information

19. According to Benjamin P. Johnson, the agent of the State of New York, appointed to attend the Great Exhibition “the chairs of the American Chiar Company, Troy, are being manufactured in England, and are much esteemed” [see Report of Benj. P. Johnson, agent of the state of New-York, appointed to attend the Exhibition of the industry of all nations, held in London, 1851] As far as we are aware there is no evidence the chairs were ever made outside Troy, and certainly not that they were made in England, and thus we suspect this was a nugget of misinformation fed to Johnson by Warren in an attempt to raise his chair’s profile. One also notes that the 1860 Chase Brothers & Co.’s illustrated catalogue claims that, “These celebrated Chairs received one of the highest premiums at the World’s Fair London”. They didn’t. Didn’t win any form of award. By 1860 Thomas E. Warren appears to have long since moved on from Troy and chairs and so it is unclear if he had anything to do with the claim.

20.The Art Journal illustrated catalogue: The industry of all nations 1851, page 152

21. Diane Mary Shewchuk, Thomas E. Warren, the American Chair Company and the Centripetal Spring Chair, MA Thesis, S.U.N.Y. Fashion Institute of Technology, February 1993

23. Jennifer Pynt and Joy Higgs, Nineteenth-Century Patent Seating: Too Comfortable to Be Moral?, Journal of Design History, Autumn, 2008, Vol. 21, No. 3 pages 277-288

24. Sir Henry Cole, Fifty years of public work of Sir Henry Cole, K.C.B., accounted for in his deeds, speeches and writings, G.Bell, London 1884, page 252

Tagged with: #officetour, American Chair Company, Centripetal Spring Chair, home office, milestones, office chair, Thomas E. Warren, Troy