"Conservative Hamburg only permits white paint for its ceilings, doors and windows, and, at most, economical gilding", remonstrated once the decorative painter Peter Gustaf Dorén.1

And set about rectifying that, set about bringing more colour to Hamburg......

Born on September 21st 1857 in Sireköpinge, southern Sweden, as Peter Gustaf Andersson, the "Dorén", we learn in the exhibition, being borrowed, usurped, from the popular 19th century French illustrator Gustave Doré, a renaming which, as the curators note, was essentially a rebranding and as such succinctly underscores Andersson/Dorén's marketing skills...... but we'll get to them..... first Andersson/Dorén must train as a painter and decorator in Lund and Eslöv, before going auf der Walz, undertaking the obligatory multi-year journey of the newly qualified tradesperson by way of completing and rounding their training; and specifically a six year journey which saw Andersson/Dorén move over stations in Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Paris and Elberfeld, before, briefly, returning to southern Sweden, and, subsequently, settling in Hamburg, where in 1887 he established a joint business with one Helmuth Harbordt. A joint business Peter Gustaf Dorén took over as sole proprietor in March 1898.

Which is, in effect, where Peter Gustaf Dorén Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 begins.

And thus at a period, as we learn in the exhibition, defined by large scale rebuilding in and redevelopment of Hamburg, and that both in terms of public/commercial/hospitality buildings and also private homes, including the villas and townhouses of Hamburg's established Old Money; and also a period, as we all (should) know, which marks the breakthrough of what we term today Art Nouveau, with its understandings of the necessity for new approaches to architecture, new approaches to the design of our objects of daily use, and also of new approaches to interior decoration.

And thereby a period which allowed ample opportunity for a young decorative painter who not only possessed ideas as to how those new understandings could, should, must, be expressed, but possessed the nous to enable him do just that.

Peter Gustaf Dorén had, one assumes, acquired the first over the course of his career, and lest we forget, when he established his own business in March 1898 Dorén was 40 and with a good two decades of experience behind him, and that in a period which had seen avant-garde understandings move increasingly away from the formal confusions of the mid-19th century avant-garde understandings, a movement that Peter Gustaf Dorén had clearly embraced; while the second brings us back to his aforementioned marketing skills, and also to a business ethos which was, by all accounts, every bit as contemporary as his work.

Or as Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 helps one understand, Peter Gustaf Dorén not only employed flat hierarchies in the company structure but also placed a great deal of responsibility and trust in the hands of the individual employees, something illustrated, for example, by a job advert in the magazine Jugend from 1908 which notes that only those capable of "working thoroughly independently" would be considered2, while the fact the advert was in Jugend that magazine which gave the German Stil of the period its name, underscoring the contemporary understandings of potential employees Dorén sought. Similarly in terms of marketing Dorén was very much up-to-date, for then and for now: on the one hand, he understood the need for a distinct, contemporary, corporate identity, and over the decades developed several which he used uniformly throughout his stationery and advertising; on the other hand he was clearly very aware of the importance of communication with customers, including maintaining more informal, almost personal, lines of communication away from the formal business communication; on the rare third hand he understood the importance of the presentation of examples of his work, of reference projects, and for which he often used his own spaces as practical examples. And on the near mythical fourth hand, Peter Gustaf Dorén networked; for the exhibition curator's a, the, key factor in Peter Gustaf Dorén's success, his adeptness as a networker, his understanding of the importance of being networked, of existing in networks, and an understanding/adeptness which saw him join all the important institutions of the period, stand in contact with all important instances, ensure he had a place on all relevant committees, regularly update his LinkedIn profile and also saw him accompany Justus Brinkmann, founding director of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, to the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, an exhibition staged very much in context of the developing Art Nouveau, and a connection with a museum very much aligned to new developments and understandings which, one presumes, greatly helped Peter Gustaf Dorén's still fledgling solo business.

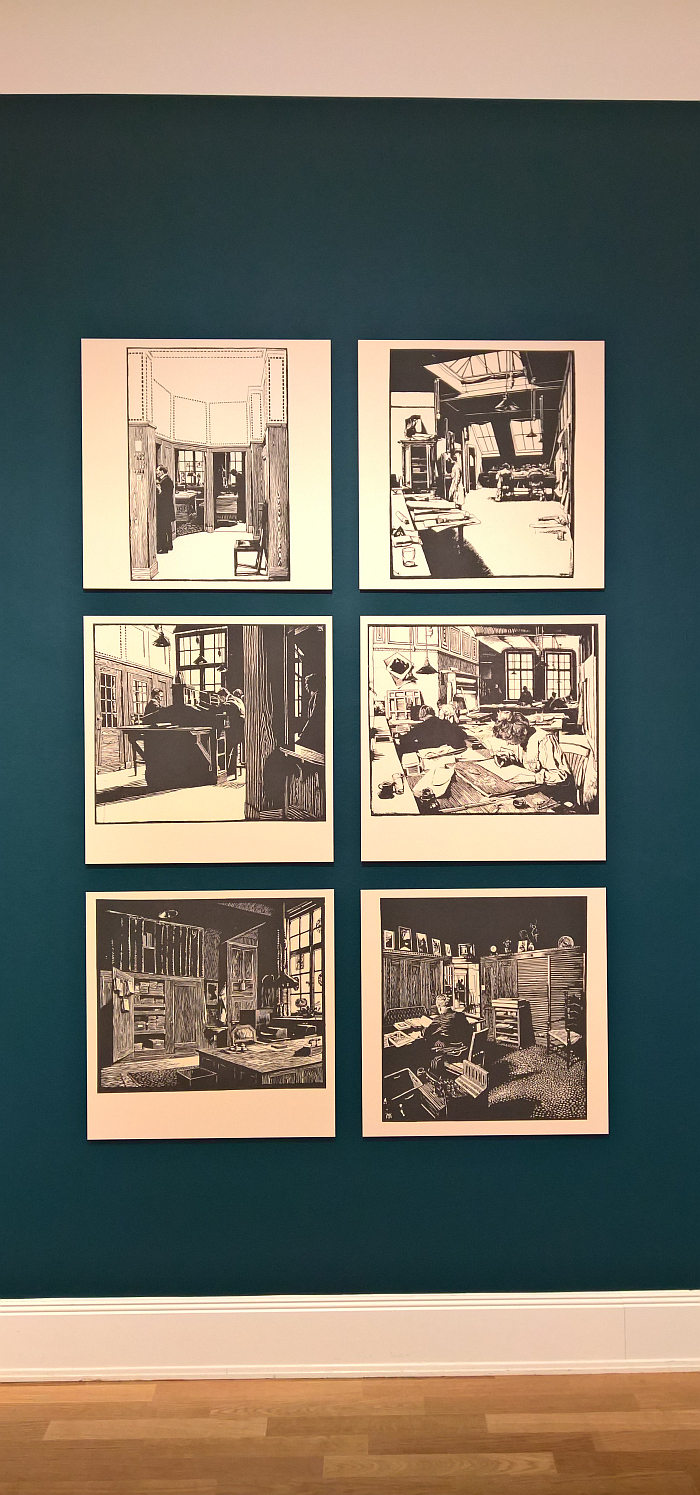

A fledgling solo business which, aided and abetted not only by the aforementioned developments in Hamburg but also, one can glean between the lines, Hamburg's shipbuilding industry which allowed Dorén to undertake numerous passenger ship interior decoration commissions, subsequently became a thriving concern; a business which went from being a primarily decorative painting company concerned exclusively with walls, ceilings, doors etc, to an interior decoration company, who took on all aspects of the furnishings, fittings and decoration; which went from employing an average of 35 staff in 1900 to an average of 135 in 1908, and at peak periods, one presumes when large commissions were in key stages, employed over 200 staff. And that at a time before handwork was industrial, was an age still very much of smaller workshops. And growth which meant, as we learn from the exhibition, regular changes of address: first to an existing building in the contemporary Adenaueralle in the Sankt Georg quarter of the city, before in 1908 moving round the corner to Pulverteich 28 and a purpose built five story office and atelier building which, by all accounts, was not only architecturally conceived to promote smooth workflows in a healthy, convivial, environment, but which linked the various floors and departments via telephone. And thus providing a very contemporary, hi-tech, and highly representative, company HQ. Also for the Kunstgewerbeverein zu Hamburg [Hamburg Applied Arts Society] who also had their registered office at Pulverteich 28. A further nice example of Peter Gustaf Dorén's networking.

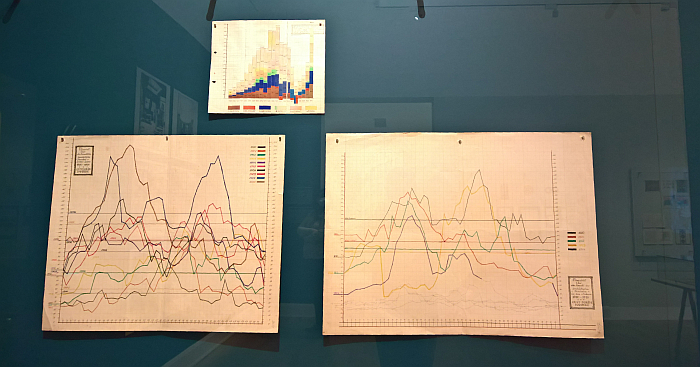

And then, as so oft in the early decades of the 20th century, came the Great War, and tellingly the chart noting the number of employees in the years 1910 - 1919 ceases abruptly in late August 1914, and so just at the moment hostilities started becoming serious, or more accurately, ceases to be formally marked in late August 1914, its steep downward trajectory being continued, as are the numbers for the War years, in an almost poetically despondent pencil grey rather than the bright hues of previous years, while the economic data records a dramatic loss in 1915. And a very strong return to profit in 1919, which might be worth reflecting on in these unsettled days of ours. Or possibly not, for the return to profitability was subsequently affected by the economic crises of the 1920s, to what Dorén refers to as "the choking of the economy", and that obviously over a prolonged period, for as Dorén laments in a letter from January 23rd 1933 to Max Sauerlandt, the, then, Director of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, the company had traded "for 3 years without earnings and at a loss, with sales at 10% of pre-War levels, at ca 50% lower prices, while the fixed costs flow unabated".3 The reference to pre-War sales in a letter written in 1933 indicating the gravity of the economic problems of the Germany of the period.

Dorén continues in his letter that, "at the age of 75 my expectation that I will experience an improvement, is low", a prognosis that the returning War sealed.

Peter Gustaf Dorén died in Hamburg on August 24th 1942, aged 84.

As an exhibition Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 takes the visitor on a thematic tour through the life and work of Peter Gustaf Dorén, and in doing so provides not only an introduction to Peter Gustaf Dorén, but also very neatly employs Peter Gustaf Dorén as a conduit by which to both approach better understandings of the development of interior decoration at a period in the (hi)story of architecture and design which saw the Gesamtkünstler architect increasingly be replaced by specialists, and thus a period which saw interior decoration establish itself as an independent design profession, become interior design, and also to approach better understandings of the evolution of formal expressions in context of interior decoration in the early decades of the 20th century.

But for all Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 takes you to colour and to Peter Gustaf Dorén's understandings of the use of colour in interior decoration and design.

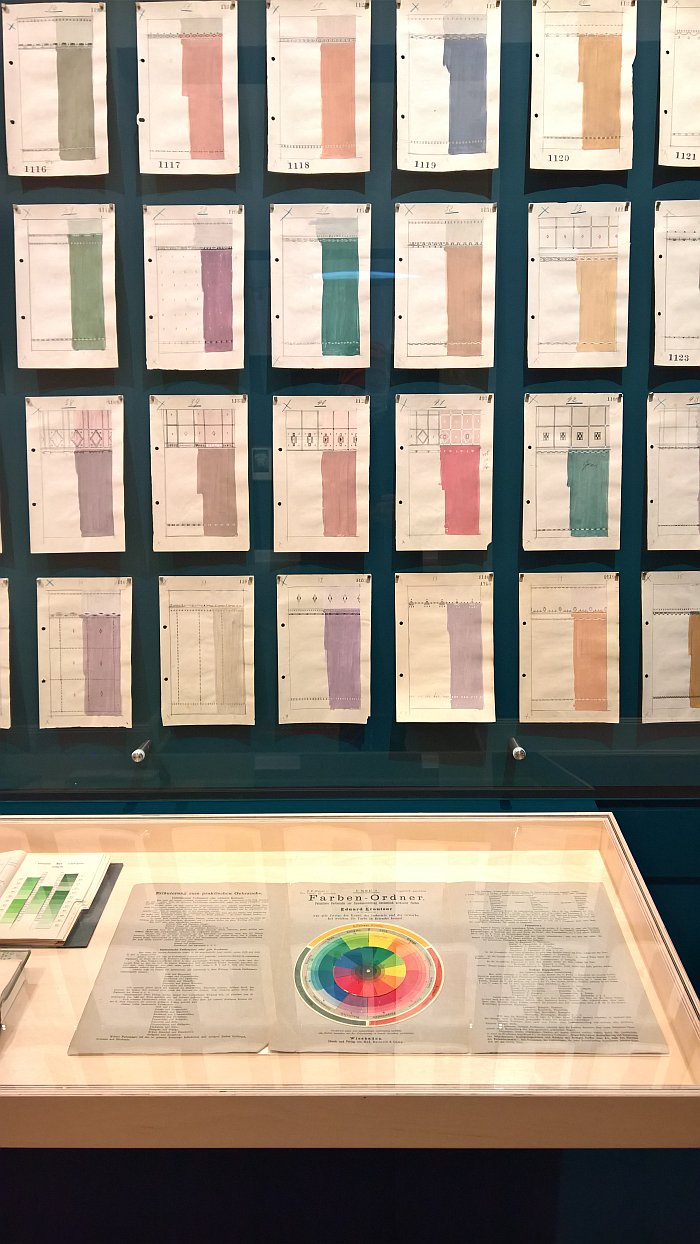

And takes you there via, for example, amongst other routes, sketches and illustrations in various formats which provided the client with a visual impression of how the room should look when finished, and which provide us today with insights into Dorén's approach, Doren's visual compositions, Doréns understandings of how colour and decoration should be used in a wide variety of contexts and scenarios, and also, if one so will, represent analogue versions of contemporary renderings, if no less descriptive and illuminating for their analogueness; via stencils Dorén and his team used to apply patterns to walls in place of the not yet readily available wallpaper, and also as, if one so will, a reduction and rationalising of the more expressive, freehand, murals that had been applied to walls by way of decoration in previous decades; or via numerous colour charts, tables and samples which help underscore that Peter Gustaf Dorén's work was based on studied, grounded, understandings of colours, on considered reflections of the colours to be used for a particular project, for all the combinations of colours to be used, and which help one approach an understanding that for Dorén colour, the combination of colours, was more than something additive in a space, was more than a passive feature of a room, but was for him a, the, key component, an active component, of the design of the space.

Opinions as to the artistic, aesthetic, value, to the quality, or otherwise, of Peter Gustaf Dorén's creations can only be formed by each and every visitor individually; however, can, must, we'd argue, be considered bold in their use of colour. Peter Gustaf Dorén wasn't a man who feared the use of colour. Wasn't a man who understood a representative space in reserved hues. Far less the logic in a white ceiling, door or window frame.

And which all reminds very much of Verner Panton's appeal, demand, for “more courage about colours”, and also Panton's position that "there should be a tax on white paint".

Peter Gustaf Dorén was there a good half century and bit before Verner Panton.

A comparison that can be reflected on more directly on the floor above Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 in the remnants of Panton's canteen design for the former Spiegel building in Hamburg, and which the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe thankfully rescued from the developers. And which allows not only for very neat reflections on the work of Peter Gustaf Dorén in more contemporary contexts, for example, what would Dorén have made of Panton's Spiegel canteen? How would Dorén have realised the Spiegel canteen? But also reflections on Verner Panton; on the one hand the reciprocal question of how a Verner Panton would have realised many of Dorén's commissions, including, and perhaps as most tantalisingly, the Thalia Theatre or Schümann's Oyster Bar for which Dorén created a collection of themed private dining rooms, which sounds just up Panton's street, and on the other, reflections on a Verner Panton, and similarly inclined designers of the 1960s and 70s, as continuations of early 20th century Art Nouveau and the drift towards Neue Sachlichkeit and International Modernism. Which isn't a context one normally considers them in. And thereby reflections on an understandings that (hi)story, including design (hi)story, rarely repeats itself, rather we're continually revolving around the same location, just in ever new contexts, with ever evolving understandings and with ever new materials and technology.

Beyond the exploration and elucidation of Peter Gustaf Dorén's use of colour as paint and fabrics, Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 also introduces Dören's applied use of colour via his patented Tilrén decorative glass concept; a concept in which two decoratively painted glass plates each featuring part of the complete composition, are bonded as one, the light passing through creating an illuminated 3D effect. Or at least we're told it does. The three examples in the exhibition not being illuminated from behind, one presumes for conservation reasons; but even unilluminated they not only indicate how the effect could have worked and what Dorén sought to achieve, but in their use of romanticised folklore, inferences of nature, a sense of the ephemeral and a Japanese longing, place them very much in Art Nouveau. And themes which allows one to understand them as a development of the aforementioned murals that Peter Gustaf Dorén realised in the earlier part of his career, before the use of colourful motifs and patterns as decoration increasingly became the use of colour, combinations of colour, as decoration.

In addition Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 presents examples of furniture by [insert details here] from [insert details here], publications such as [insert details here] which either feature Dorén or were penned by him, examples of greetings cards, ex libris and similar stationery items by Dorén for the likes of [insert details here], a selection of paintings by Dorén of [insert details here] from [insert details here] and similar objects which help round understandings of Peter Gustaf Dorén and his work.

And which, we'd argue, would do more so if [insert details here].

Or put another way, there are no signs/labels telling you what the objects are, when they are from or their relationship to the life and work of Peter Gustaf Dorén. Why? We no know, but it is a highly curious omission. Or maybe we just missed them. Even if we can't work out how we could have missed them. And while in most cases one can discern what you're looking at and its relevance to Dorén's life and work, in other cases one can only guess. And hope you're right. And which while, yes, is a weakness in the presentation format, isn't as dramatic as it could be as the larger part of the presentation relies on objects of similar sorts, for example sketches, illustrations, draughts of interiors, colour samples or examples of Dorén's various corporate identities, and which are often either self explanatory or labelled in that information is written on them.

But, yes, external labels would be most helpful.

And while we're finding fault. Which we never enjoy doing, but while we're here, the biography of Peter Gustaf Dorén comes, for us, a bit short in the presentation. We're told, for example, that he changed his name from Andersson to Dorén, but not when, one presumes post-Paris, but....?; we're told that he moved to Hamburg's Sankt Georg quarter, but not from where or indeed when, one presumes around 1904/05, but........?; we read that in the early 1930s he left Hamburg, but know not for where, one presumes in the close vicinity, perhaps somewhere that today is Hamburg, but....?

And while, yes, the exhibition is primarily about Dorén's contribution to the development of interior design as a profession, the Hamburg of the first decades of the 20th century, and for all Dorén's use and understandings of colours, given that the exhibition is also introducing Peter Gustaf Dorén to a whole new public, a bit more biographical information would be desirable.

Whereby it is important to note that an accompanying book is ........ due in April, and which should fill in many of the gaps in the biography and also [insert details here].

Which isn't to dismiss Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900, isn't to say ignore the exhibition and buy the book, far from it; as a presentation Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 allows for an accessible, informative and entertaining introduction to the life and work of Peter Gustaf Dorén, one which tends to an understanding that while Peter Gustaf Dorén may not have been an absolute key figure in the developments of design in the first decades of the 20th century, on account of the works he realised, and for all the formal and conceptual development of those works over the decades, but also through the connections he kept, the circles in which he moved, and the businesses practices he.... well, practised, Peter Gustaf Dorén is very much someone who can help us all move towards more probable understandings of the formal aesthetic developments of the early decades of the 20th century, help us all move towards more probable understandings of the development of interior design as an independent profession, and also allow for reflections on how far, or perhaps more accurately, how not far, the interior design industry has developed in terms of project development processes and business, marketing, practices since the early decades of the 20th century. And is also someone who can help us all further our own understandings of and positions to the use of colour in interior design.

And thus even if the biography were fuller and the objects labelled, Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 would and could, by necessity of limitations of time and space, be but the start of a more thorough exploration of its subject matter and themes.

And as an exhibition it does more than enough to indicate that exploration could be well worthwhile, and thus recommends itself as an meaningful starting point.

Wandering through Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900, reflecting as one does on Peter Gustaf Dorén, his work, interior design and the development of the interior design profession since 1900, the thought keeps on returning that Peter Gustaf Dorén would have been all over Instagram; @pgd_hh would unquestionably have been one the better subscribed profiles in the first decades of the 20th century. And that not just on account of the contemporaneous of Dorén's work, and the very obvious attraction of such brightly coloured images for the contextlessness of social media, but as an adept networker Peter Gustaf Dorén would have instinctively understood the benefits of visual social media and would, one presumes, have invested heavily to increase his visibility and penetration. And in Hamburg there are no shortage of freelance digital media professionals who could have assisted.

Thoughts which automatically lead on to the reflection that our understandings of the early decades of the 20th century are somewhat coloured, pun intended, by the fact that the photos of the period are black and white, a state of affairs which tends to lead us to the assumption that the interiors of the period lacked colour. And while many invariably did, as Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 helps explain, many domestic, public and commercial spaces were highly colourful affairs.

Thoughts which bring us back to Luigi Colani's argument that while Bauhaus understood itself as brightly coloured geometry, contemporary Bauhaus understandings are achromatic and quadratic.

And thereby towards an understanding that in the course of time colour fades from our collective memory.

Or put another way, when we think of the interiors of the first decades of the 20th century, we think in terms of objects, for all furniture, we think in terms of materials, in terms of formal expressions, of ornamentation, of functionality; we don't think in terms of colour. And certainly don't think in terms of colour as an active component of that space. And in doing so exclude a key component of the actual experience of the actual interiors, and thus limit our understandings of the period, and by extrapolation reduce our ability to fully understand developments since then.

Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 helps remind us of the error of our ways, of the necessity of considering early 20th century interiors in their full sensory complexity.

And helps restore the visibility Peter Gustaf Dorén once enjoyed, helps Peter Gustaf Dorén reclaim his place on design's helix and allows him and his contribution to the development of design understandings to be considered and analysed in context of his contemporaries, our contemporaries and all those contemporaries who've came in between; and for all allows for reflections on the passion for colour which underscored much of Peter Gustaf Dorén's understandings of interiors; a passion for colour which he successfully convinced the conservative classes of Hamburg to permit for their ceilings, doors, windows, walls, floors, facades......

Peter Gustaf Dorén. Interior Design in Hamburg circa 1900 is scheduled to run at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Steintorplatz, 20099 Hamburg until Sunday May 30th

Full details can be found at www.mkg-hamburg.de/peter-gustaf-doren

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

And for all who can't make it to Hamburg, or indeed all who can but wish to prepare, a short tour through the exhibition courtesy of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in the company of Peter Nils Dorén, Peter Gustaf's great grandson (spoken German, English subtitles, ca 7 minutes)

1Unreferenced quote in exhibition

2Jugend, Volume 13, Nr. 20, 1908 page 471 available at https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/jugend1908_1/0497 (accessed 18.03.2021)

3Letter from Peter Gustaf Dorén to Max Sauerlandt, January 23rd 1933, displayed in exhibition