The contemporary systematics of the family Cactaceae recognises four subfamilies, Cactoideae, Maihuenioideae, Opuntioideae and Pereskioideae; is however a classification very much in motion, one very much in an ongoing process of re-evaluation, re-definition, re-assessment, one which undergoes regular revisions.

¿An ongoing re-evaluation and re-definition and re-assessment and revision which could see the addition of a fifth subfamily, the Craftoideae?

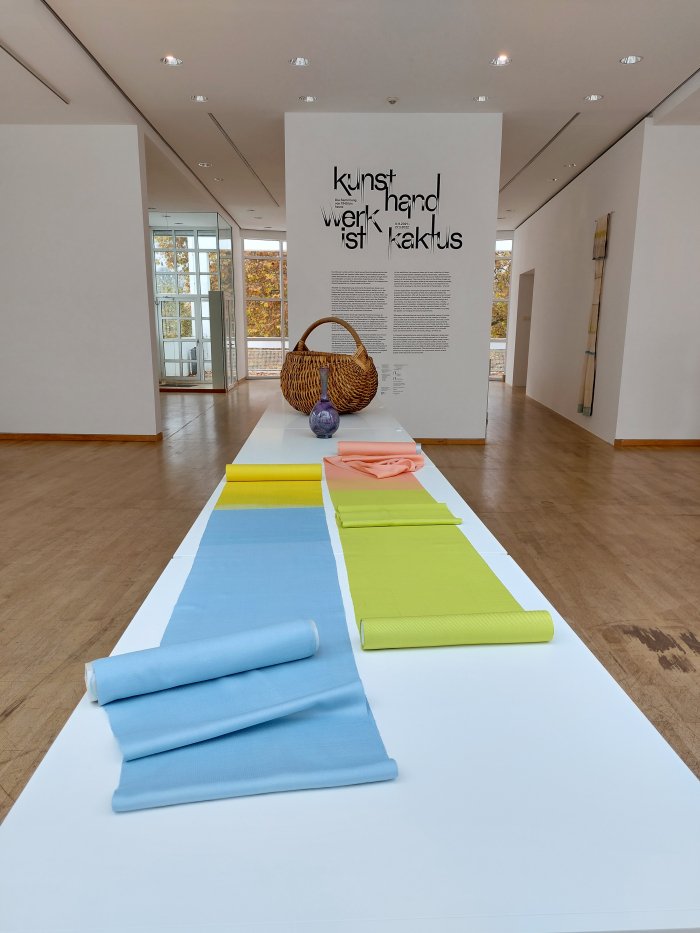

With the exhibition Craft is Cactus. The Collection from 1945 to Today the Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt, explore contemporary craft in its myriad expressions, positions and relationships, and in doing so also undertake an appraisal of the contemporary taxonomy of our objects of daily use.......

The Museum Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt traces its history back to the second half of the 19th century and the founding by the Mitteldeutsche Kunstgewerbeverein of a library, a school and a Kunstgewerbe museum, and thus common institutional additions to many European cities against the background of the developing industrialisation of the second half of the 19th century; yet whereas the focus of contemporaneous institutions such as the V&A in London or the MAK in Vienna was, as Craft is Cactus's curator Sabine Runde notes, advancing that developing industrial production, "the focus of the collection in Frankfurt was on Kunsthandwerk".1

The Kunsthandwerk of the exhibition's German title, Kunsthandwerk ist Kaktus.

A Kunsthandwerk that as a term is not only as complex to define in German as it is to translate in to English2, but also a term that is as difficult to cleanly separate, in both German and English, from the Kunstgewerbe of the original Frankfurt museum and the Angewandte Kunst of the contemporary Frankfurt museum.

A linguistic challenge that is one of the pillars on which Craft is Cactus. The Collection from 1945 to Today is built; or perhaps better put a central pillar of Craft is Cactus is reflecting on craft in context of, with reference to and in contrast to, Angewandte Kunst [Applied/Decorative Art, Arts & Crafts] and Kunstgewerbe [Applied/Decorative Art, Arts & Crafts]. And that as the subtitle neatly confirms, from 1945 to Today.

A time-frame not chosen to avoid historical reflections, but much more by way of keeping the focus of the study on contemporary craft and contemporary society.

And also because the second half of the 20th century sees, in many regards, the breakthrough of an important fourth term, a fourth term to add to the Kunsthandwerk/Kunstgewerbe/Angewandte Kunst dialectic: Design.

There is a popular argument that design as a profession and verb arises around 1900 as, and simplifying more than is prudent, a re-imaging of Kunsthandwerk/Kunstgewerbe/Angewandte Kunst in context of evolving social, economic, technological, et al realities, a re-imagining that became increasingly industrial in the 1920s and 1930 before post-War realities, post-War needs, saw industrial production, and its enabler design, very quickly become accepted as a normal and natural process via which to produce our objects of daily use. In many regards became the only viable option. And saw industrial production and its designers supersede craft production and its artisans.

A development which not only impacts on the definitions, translations and distinctions in the matrix of processes by which objects of daily use are developed and produced, but, as Craft is Cactus's curators opine, meant that post-1945 craft found itself with the choice of going over fully to function and thereby ignoring its artistic traditions or going fully to decorative and thereby ignoring its utilitarian traditions; as Craft is Cactus helps elucidate, craft choose to be both, and neither, or as Eva Linhart notes "is a discipline that today is diffusely located between the purposelessness of fine arts on the one hand and the functional demands of design on the other".3

To which, and after viewing Craft is Cactus, we'd add that, and as noted from The Magic of Form – Design and Art at Kunsten, Aalborg, much as design and art, by necessity of evolutions and developments in society, have evolved and developed in the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, so craft has in and of itself developed and evolved alongside society; and just as we suggested from Aalborg that a factor in the development of both art and design in the 20th century could, possibly, be understood in a need on the part of both to maintain a distance, an independence, from the other, while freely and happily letting oneself be informed by the other, so, we'd argue, the need to maintain its position as neither an artistic practice nor a design practice has played a role in the developments of craft since 1945. That a key motivation in the development of craft practice since 1945 has been a desire to remain "diffusely located" between art and design.

A diffusely location that can be observed and studied and questioned and approached in Craft is Cactus.

Presenting itself in a depot-style showcase more familiar in context of permanent collection exhibitions, Craft is Cactus takes the visitor on a multi-faceted journey through materials and time: its various chapters focussing on a single material, arranged chronologically in decade sized blocks, and as represented by a wide variety of processes; thus, for example, the chapter Ceramics features examples of modelling, free turning, template turning, casting, cutting, faceting, inlaying, glazing, painting and firing from across the decades and as represented by objects that form a span from the more decorative to the more utilitarian, and from the unique individual to the serial reproducible.

And which in doing such not only allows for reflections on the development of craft, nor only on the developments in formal understandings, of production processes or of technological integration in context of the various materials, but also helps underscore the primacy of materials in craft, helps underscore the kinship between a craft and a material, helps underscore that whereas, for example, design can be considered, for example, an exercise in problem solving where the material is chosen on the basis of what is considered optimal for the given solution in the given context, craft starts from the material and seeks to employ that material to achieve the desired end. And while the results can be very similar, they are in their essence very, very different.

Differences and similarities which are components of the systematic study of our objects of daily use and which make compiling a universal, stable, taxonomy so very difficult.

But as Craft is Cactus teaches, a systematic study that exactly on account of its complexities is immensely satisfying to undertake.

In addition Craft is Cactus allows for appreciations of how over the decades industrial production has continually borrowed from craft production, the debt of gratitude industrial production owes craft production, something for us, and that, arguably, on account of our unique way of viewing the world, best exemplified in furniture, for all chairs: Arne Jacobsen's Ant, for example, or Peter Hvidt and Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen's Ax Chair, which although, for us, are both design objects, were both dependent for their genesis on contemporaneous developments of craft processes; similarly the Eames Wire Chair, again for us a design object, yet one which, as previously noted, arose in the early days of attempts to make goods industrially from the long established practice of weaving wire. And all three works in which the material, the understanding of the material and necessity of working in harmony with the material, that which as Eva Linhart argues in the Craft is Cactus catalogue is "an essential prerequisite for craft creation" is very obvious, very apparent.4 Yet also very much not the works' singular attribute, is but a part of a much wider whole.5

In a similar vein Craft is Cactus helps elucidate how machines have increasingly been employed to undertake jobs once done by hand, and in doing so further blurring boundaries between craft and industry, something neatly encapsulated in the ever deceptively simple Ulmer Hocker, a work whose construction principle, as noted from Idea ─ Icon ─ Idol at the HfG-Archiv Ulm, is based upon Fingerzinken, finger joints, a classic craft technique but an object which was devised, designed, to be produced 20% by hand and 80% by machine, an object whose Fingerzinken are cut by a machine using a specially designed jig, and thereby enabling rapid, serial production. And which makes the Ulmer Hocker a craft product or an industrial product?

Considerations on the relationships between machines and industry and craft very much embodied in Günter Beltzig's Floris moulded plastic chair; while we did once anoint Christian Dell as father of the craft of the Plasticsmith, plastics ain't a material popularly associated with craft. But why not? If craft is a material centred approach to developing objects of daily use which exists diffusely between art and design, can there be limitations on the materials that are craft?

In context of Louise Brigham we argued that through developing a system for turning wooden packaging waste into furniture she developed a new craft. Can one not make the same argument that the use of recycled plastic packaging waste to create new objects of daily use is also a craft? One that could only arise when the requisite materials and technologies were available, identified and understood? Or are such arguments invalid sub-divisions of the species Cabinet-Maker and Plasticsmith?

And where does developing production technology leave craft? Is a 3D printed ceramic vase craft? Is a 3D printed wooden chair craft? Does Paul Hildinger and Josef Schlecker's jig for the Ulmia 1615 circular saw mean the Ulmer Hocker can't be considered a craft product? What function does analogue, tactile, craft have in an increasingly digital, virtual world? Can craft exist in the Metaverse? Should craft exist in the Metaverse? Should the Metaverse exist?

Questions on the future of craft the Museum Angewandte Kunst's exploration on contemporary craft very naturally leads you in to, which neatly expand the scope of Craft is Cactus and which further complicate the process of establishing a universal, stable, taxonomy of our objects of daily use.

And add to the satisfaction of that process.

And to the satisfaction of Craft is Cactus.

An expansive and diverse presentation, yet never distractingly or confusingly so, Craft is Cactus is a tightly focussed and accessible presentation which, and much as with a cactus house in a botanical garden, sees species normally geographically far removed from one another reside side-by-side in an artificial landscape, is a curated showcase which presents diverse objects thoroughly out of context; but a presentation format that is necessary in the cactus house for both enabling direct comparisons of different expressions of "cactus" and posing the question what is "cactus"? And which in the Museum Angewandte Kunst is necessary for enabling direct comparisons of different expressions of "craft" and posing the question what is "craft"? What is Kunsthandwerk? What is Design? What is Kunstgewerbe? What is Angewandte Kunst?

And a presentation which aside from its museal intents can also be approached and viewed as a collection of objects of various types and genres to be explored as individual objects within and of themselves; a presentation in which, and as with the cactus house, all will invariably be drawn to different examples, in our case the principle delight was the chance to reacquaint ourselves with objects we don't see that often, including Ferdinand Kramer's Rainbelle paper umbrella, Peter Hvidt and Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen's aforementioned Ax Chair, or Diana Stegmann's woven wicker baskets, works we first saw at Tendence Frankfurt 2015 and which have lost nothing of their engaging and challenging character, have lost none of their easy comparison with your average Berliner, over the years. And which are and were without question the closest thing to a real cactus in the presentation, the closest embodiment of Craft as Cactus.

But is Craft a Cactus?

Can one add the Craftoideae to the Cactoideae, Maihuenioideae, Opuntioideae and Pereskioideae?

Cacti are extremely variable in their expression.

Cacti can readily adapt to new conditions.

Cacti are important for supporting communities.

Cacti can be decorative, but needn't be.

Cacti can be utilitarian, but needn't be.

Cacti are resilient.

Cacti have few external demands.

Cacti are locally native but can be cultivated globally.

Cacti are survival specialists.

Cacti are versatile.

Cacti contain a myriad species and subspecies.

Cacti cannot be readily grasped.

Craft is a classification very much in motion, one very much in an ongoing process of re-evaluation, re-definition, re-assessment, one which undergoes regular revisions.

¿Can one add the Craftoideae to the Cactoideae, Maihuenioideae, Opuntioideae and Pereskioideae?

Craft is Cactus. The Collection from 1945 to Today is scheduled to run at the Museum Angewandte Kunst, Schaumainkai 17, 60594 Frankfurt until Sunday March 27th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.museumangewandtekunst.de/craft-is-cactus

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious.......

1Sabine Runde, Die Verwendung des Begriffs Kunsthandwerk und seine Historie, in Sabine Runde and Matthias Wagner K [Eds.] Kunsthandwerk ist Kaktus, Arnoldsche, 2022 [Owing to ongoing supply chain problems the global publishing industry is unable to print as quickly as it would like to, which means that as of writing the Craft is Cactus catalogue is not yet available, is however scheduled to be published in April 2022. We have advance [working] copies of Sabine Runde and Eva Linharts' chapters, for which we are grateful and thankful]

2Kunsthandwerk is a compound of Kunst, Art and Handwerk, Craft, and can thus be considered as "artistic craft", whereby the question of the art in craft is obviously subjective and most craftsfolk would consider themselves as also being responsible for any artistic forming and thus making the "artistic" in "artistic craft" superfluous, ergo Kunsthandwerk = Craft. But you do then need to define "craft" in English, and for all separate it from "trade" and also "artisanal"... The fact that Germans employ, but are barely able to differentiate between, Kunsthandwerk, Kunstgewerbe and Angewandte Kunst invariably has its origins in the structure and development of Germanic languages past and their forming into contemporary German. A clear out and re-ordering could be considered highly advisable, but 🤫 don't tell any Germans we said that, they'll be furious.....

3Eva Linhart, Abenteuer Kunsthandwerk in Sabine Runde and Matthias Wagner K [Eds.] Kunsthandwerk ist Kaktus, Arnoldsche, 2022 [see as FN 1]

4ibid

5We'd also add that the same can be said of the Thonet bentwood chairs from the mid-19th century, works which for us are design objects and also mark the start of industrial production of furniture, and thus the start of a lot of the complications in terms of defining and distincting between craft and industry.