HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever at the Bauhaus Building, Dessau

“Exhibiting means selecting, emphasising, demonstrating as a model or an example”, wrote Klaus Wille in his 1960 Diploma thesis at the Hochschule für Gestaltung, Ulm, continuing that, “the object is information. This information can be used for didactic, commercial or representative purposes. Aimed at individuals as consumers of products and ideas, the exhibition is used to educate, canvass and represent, to influence people, to get them to react in certain ways.”1

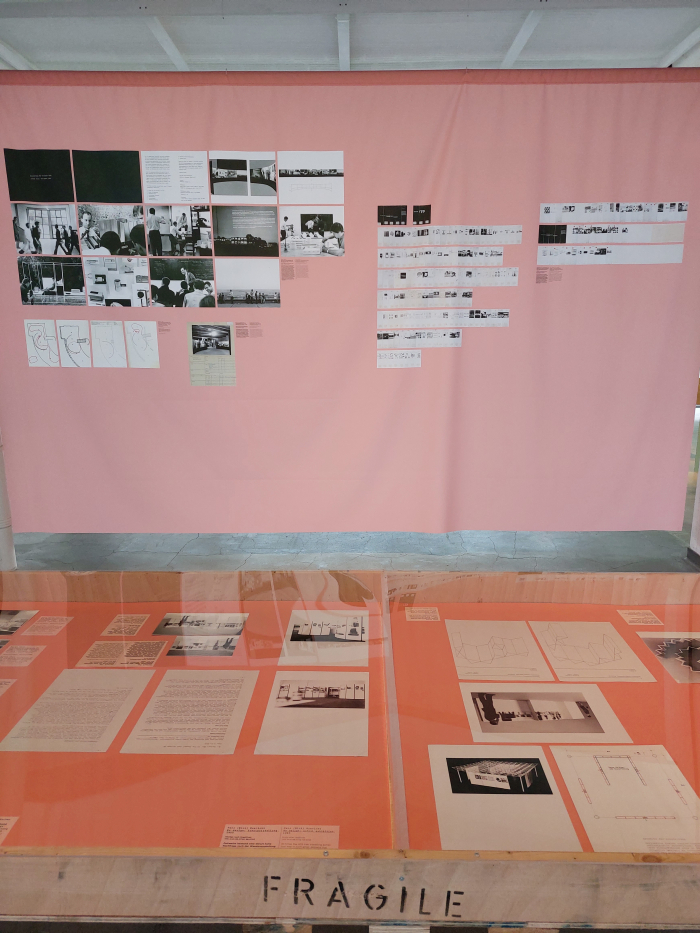

The exhibition HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever at the Bauhaus Building, Dessau, explores how the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm not only educated, canvassed and represented through the media of exhibition design, but how they thereby contributed to the development of the practice and theory of exhibition design……

Formally opened in August 1953 as an offshoot of the Ulmer Volkshochschule, as an offshoot of the ideals of the Ulmer Volkshochschule for a democratic re-start in the new West Germany after the years of Nazi dictatorship, for all that the Hochschule für Gestaltung, HfG, Ulm, is often considered the official unofficial Bauhaus successor institute it had, and as oft noted in these dispatches, a very different understanding of itself, or as Tomás Maldonado stated at the opening of the 1957/58 academic year, “trying to literally continue Bauhaus would be tantamount to a merely restorative endeavour … We only adopt its progressive, anti-conventional stance – striving to make a contribution to society in its own historical situation. In this sense, and only in this sense, are we continuing the work of Bauhaus”.2

A 1957/58 academic year that was the first following the departure of founding Rector, and ex-Bauhäusler, Max Bill and which thus marked the first academic year in which the school tangibly moved away from Bauhaus practice and began to enact and express its own understandings of a contemporary “progressive, anti-conventional stance”; and a 1957/58 academic year in which HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever‘s exploration of exhibition design at the HfG Ulm, more or less, begins with the so-called Mensa Exhibition of 1958, so-called because it was an Exhibition which via some 100+ display panels hung in the school’s Mensa sought to convey the pedagogic concept of the HfG Ulm, the so-called Ulmer Modell, that which saw it move away from a primacy of art in the creation of our objects of daily good and focus instead on engineering and science and technology, where design was understood as being based on objective analysis not subjective intuition, design being a process one learned in seminars not a talent one mastered in ateliers. And an exhibition that for all it represented a confirmation of a break with Bauhaus, can also be considered akin to the 1923 Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar, an exhibtion which in its own way sought to explain Bauhaus and its avant-garde positions on creative education and the priorities in the development of objects of daily use to its contemporary audience.

Not that the Mensa Exhibition was the first HfG exhibition, as Exhibition Fever helps elucidate by 1958 the HfG were, despite their relative youth, well versed in exhibition design and had, amongst other projects, developed the concept for the 1954 exhibition Gutes Spielzeug [Good Toy], an exhibition which presented toys that were considered particularly recommendable, a relative novum at that time, and an exhibition which following its premier in Ulm travelled globally; in 1955 had been responsible for Braun’s exhibition stand at the Große Deutsche Rundfunk-, Fernseh- und Phono trade fair in Düsseldorf, that trade fair which was so pivotal in helping Braun establish themselves in post-War West Germany; and in 1956 had staged an exhibition about themselves in the Museu de Arte Moderne, Rio de Janeiro. Three early HfG Ulm exhibitions which represent different aspects of the educating, canvassing and representing for didactic, commercial and/or representative purposes Klaus Wille refers to, and three exhibitions which help elucidate important aspects of both the HfG Ulm’s understanding of the role and function of the exhibition in the post-War realities, and the HfG Ulm’s contribution to the development of the practice, and theory, of exhibition design.

“Exhibition architecture is a crucial medium of exhibition design, often the decisive factor”3, opined HfG Ulm co-founder and leading protagonist Otl Aicher in 1960; yet whereas in decades past that exhibition architecture had been actual buildings specially developed for the exhibition, by 1960 the primary focus was the exhibition stand.

But, asked Aicher “what requirements do we demand of an exhibition stand in terms of a constructive and spatial solution?”4

???

First on Aicher’s list of answers was the requirement that “apart from exceptions, an exhibition stand is not an individual, single-use, object. It should be able to be used repeatedly”, a requirement from which, for Aicher, further requirements naturally and automatically flowed, including, and amongst others, that an exhibition stand should be convenient in its construction, should be readily transportable/storable, should be flexible, should allow internal and external variation, requirements that Aicher discusses as also being those required by building construction systems responsive to contemporary needs; conditions that today form the self-evident basis of the design of any exhibition conceived to be presented in more than one location, but conditions that, arguably, the HfG Ulm were one of the first to fully embrace, one of the first to fully comprehend as necessary to allow the exhibition, be that a didactic, commercial and/or representative exhibition, to play a meaningful role in the developing societies of that period; conditions that, arguably, one couldn’t have arrived at from a Bauhaus-esque primacy of art perspective, conditions that required a differentiated continuation of inter-War positions into post-War society.

And conditions which led the HfG Ulm to develop tailored exhibition stand systems for their exhibitions. The first of which being that for Gutes Spielzeug, a system which can be explored and analysed in Exhibition Fever, and which also led to the development by Otl Aicher and, the then student, Hans G. Conrad of the so-called d55 exhibition stand system for Braun, so-called because it premiered in düsseldorf in 1955, and a system which, as noted from Braun 100 at the Bröhan-Museum Berlin, was used for all Braun exhibition stands for the next 20-ish years. Testament we feel not only to its suitability and adaptability but also to its close association with Braun’s self-image under Fritz Eichler, and how that changed after Dieter Rams began defining the brand in the 1970s.

And a cooperation with Braun that is perhaps that most popularly known example of how the HfG Ulm were not only at the forefront of the development of design in its various hues in post-War West Germany, but how the HfG Ulm contributed to the post-War economic recovery in West Germany, and assisted the post-War rehabilitation of West Germany.

And did that not just through representing others, but through representing themselves as an integral component of that new, open, global, progressive, definitely non-Nazi, West Germany

Or put another way, Exhibition Fever helps one appreciate that the educating, canvassing and representing the HfG Ulm undertook was often very much in the context of the HfG Ulm.

Otl Aicher relaxing on the Gutes Spielzeug exhibition stand system, as seen at HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever, Bauhaus Building, Dessau

In 1963 the HfG Ulm staged an exhibtion at the Landesgewerbeamt Baden-Württemberg in Stuttgart which, as with the 1958 Mensa Exhibition, sought to explain the HfG in some 100+ display panels; the difference being by 1963 the Ulmer Modell was up and running and had results to show, and critics to contend with; critics Otl Aicher didn’t directly address in his speech at the exhibition’s opening, but indirectly very much did.5 And a 1963 exhibition which over the next two years was shown in the Ulmer Museum, Die Neue Sammlung München and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, the latter being indicative of an international interest in the HfG Ulm documented by Exhibition Fever, and which in addition to the aforementioned exhibition in Rio de Janeiro, saw the HfG Ulm present themselves at the XII Triennale di Milano in 1960 and also saw Tomás Maldonado, a man who although not amongst the founders of the HfG Ulm was amongst its most influential shapers, invited to lecture at events, and to serve tenures as a guest lecturer at institutions, across the globe.

If an international interest that didn’t extend to the hallowed halls of the Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, New York, that institution that was so pivotal in not only bringing the Bauhauses to America but in establishing the basis for much of the mythology that surrounds Bauhaus today, not least through their staging of the 1938 exhibition Bauhaus: 1919–1928. And an institution whose, then, Director of the Department of Architecture and Design, Arthur Drexler rejected in 1965 the idea of presenting the 1963 Stuttgart exhibition at the MoMA, noting that while he approved of the HfG Ulm and what they were doing, he didn’t think they were particularly relevant, opining that “neither the Braun Company nor the HfG has any particular claim to having “triggered a design revolution””, and that a comparison of the HfG Ulm “with the Bauhaus [is] more misleading than enlightening”.6 Should the MoMA be looking for an exhibition theme involving European design, Drexler’s opinions may provide an interesting starting point for a more critical discourse than he was prepared to allow.7

And an international visibility, and a contribution to exhibition design practice, that, arguably, reached its zenith at the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal, an event for which the HfG Ulm not only presented itself in context of the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design’s student showcase The New Designers, but for which the HfG Ulm in the guise of a team led by Herbert Ohl und Herbert Kapitzki were responsible for the design of the exhibition Man and the Community which was staged within the German Pavilion; a 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal with which Exhibition Fever ends. And a 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal staged but a year before the HfG Ulm itself ended.

A 1968 closure of the HfG Ulm which although it marks the end of the HfG Ulm’s direct association with exhibition design, doesn’t mark the end of the HfG Ulm’s influence on the practice and theory of exhibition design: not only did many of the institution’s staff and students go on to play important roles in West German exhibition design, in the further development of exhibition design in West Germany, but as Exhibition Fever allows one to better appreciate the work the HfG Ulm undertook in the 15 short years of its existence still informs and influences global exhibition design practice and theory.

Tomás Maldonado reflects on his travels in context of the HfG Ulm, as seen at HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever, Bauhaus Building, Dessau

Not that the HfG Ulm were alone in such developments, amongst the many other names one could, should, must, mention the more relevant in context of the HfG Ulm, arguably, include the likes of a George Nelson or a Charles & Ray Eames who played very important roles in re-imagining what an exhibition could, should, must, be in the 1950s and 1960s; or a Le Corbusier whose Poème électronique concept for the Philips’ Pavilion at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels as an immersive multi-medial experience exploiting the possibilities of contemporary technology stands diametrically juxtaposed to the reduced, analogue, poster format of the parallel running HfG Ulm Mensa Exhibition.

In addition viewing Exhibition Fever we were continually reminded of a creative not mentioned, and who, as best we can judge wasn’t an influence of the development of exhibition design at HfG Ulm, but who, inarguably really should have been: Lilly Reich.8 As previously noted, in the inter-War years Lilly Reich played an important role in developing exhibition design practice in the contemporary Germany, moving on from sales presentations in department stores to designing exhibitions for the Deutsche Werkbund and like-minded companies, exhibitions which stood out on account of their reduction, objectivity and clarity, which went new ways in the presentation of information, in the manner by which they educated, canvassed and represented, and were, arguably, exactly that which an Otl Aicher demanded. Yet, for example, when in 1960 Otl Aicher notes that exhibtion design was in “einer akuten Krise“9, “an acute crisis”, that contemporary exhibition design was an unsatisfying “exuberant play with materials, shapes and colours” and that “exhibition design has become an end in itself”10, he doesn’t reflect on the contemporary in context of what a Lilly Reich was doing four decades earlier. Which, arguably, he could have done. And which could indicate that by 1960 Lilly Reich had already slipped hopelessly into obscurity in West Germany, smothered by the shadow of Mies, or could underscore the degree to which with the departure of Max Bill, both an ex-Bauhäusler and active Werkbündler, the HfG Ulm not only sought to distance itself from Bauhaus but from the Deutsche Werkbund, and is certainly, we’d argue, worthy of further investigation.

And in a similar inter-War context, if we did miss one thing in Dessau it was a comparison of exhibition practice at the Bauhauses with that at the HfG Ulm; Bauhaus not only staged a couple of exhibitions themselves, including the aforementioned Weimar 1923 and New York 1938, but also entertained cooperations with, for example, the Grassi Museum Leipzig, and, and lest we forget, exhibtion design was taught at Bauhaus from 1923 onwards. The HfG Ulm didn’t introduce it to Germany. But how does exhibition design à la Bauhaus compare and contrast with exhibition design à la HfG Ulm? For all in context of the HfG Ulm’s understanding of its relationship with Bauhaus? How does a Herbert Bayer contrast with an Otl Aicher? Does our claim above about Otl Aicher’s position on exhibition stands not being possible at Bauhaus hold up under investigation? We’re not saying that the Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau should have produced something to the scale of Exhibition Fever, that would be a ridiculous demand; are saying a few posters and objects as a (short) fifth chapter would have been a very welcome, interesting, meaningful, extension of Exhibition Fever. And thereby its absence must be seen as an opportunity missed.

The HfG Ulm’s contribution to the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal, as seen at HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever, Bauhaus Building, Dessau

Curated by the HfG-Archiv Ulm in cooperation with the Folkwang Universität der Künste Essen and the Hochschule Pforzheim, Exhibition Fever premiered in Ulm in the summer 2021, in that brief window when such was possible, and through its pleasing mix of documents, photographs, reproductions of elements of exhibitions, and other supporting archive material, allows one to not only approach a better appreciation of how the HfG Ulm contributed to the evolving understandings of the exhibition and exhibition design in the immediate post-War years, and that, again lest we forget, a period when the exhibition was taking on an ever greater commercial and social significance, but is a presentation which in doing so, which in exploring beyond the exhibitions themselves and elucidating how they arose, why they arose, the positions that flowed into them, and the contexts in which they were presented, enables access to differentiated views of the HfG Ulm as a component of the rehabilitation and reinvention of western (Nazi-)Germany as West Germany, differentiated views of the reception of the Ulmer Modell in West Germany, differentiated views of the position of the HfG Ulm in a global context rather than the local West German context in which it is normally considered. And thereby allows access to a more probable appreciation of not only the influence of the HfG Ulm during its brief existence, but its contemporary legacy.

And is an exhibition about the HfG Ulm that while, one suspects, wouldn’t necessarily have served the canvassing and representative purposes the HfG Ulm sought, wouldn’t neceassrily have influenced viewers as the HfG Ulm sought to in its own exhibitions, is an exhibition about the HfG Ulm that uses objects as information for didactic purposes staged in an exhibition design concept which is convenient, transportable, flexible, can “be used repeatedly”, and thus an exhibition that is very much in the tradition of the exhibtion and exhibition design as understood and practiced at the HfG Ulm. And thus an exhibition that is in itself a model, an example, an object as information.

HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever is scheduled to run at Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Bauhaus Building, Gropiusallee 38, 06846 Dessau-Roßlau until Sunday March 6th.

Full details can be found at www.bauhaus-dessau.de/exhibition-fever

In addition the bilingual German/English Exhibition Fever project website contains, alongside brief background information on the school, its protagonists and exhibitions, archive photos from HfG Ulm exhibitions and texts from the likes of Otl Aicher or Tomás Maldonado.

In addition addition, until Sunday February 20th the Bauhaus Lab exhibition Vegetation Under Power – Heat, Breath, Growth can also be viewed in the Bauhaus Building, Dessau.

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……

1. Claus Will, Ausstellungsgestaltung, HfG Ulm, August 1960, HfG-Arch Dipl. 61.9, and presented in Exhibition Fever. Klaus Wille is sometimes written as Claus Wille, including by himself on his thesis, that Klaus appears the more regular and common version, and that which he himself appears to have used in later years, we’re going that.

2. Tomás Maldonado, Speech at the beginning of the 1957/58 academic year, October 3rd 1957, HfG Archiv PA 656.2, and presented in Exhibition Fever.

3. Otl Aicher, Ausstellungsgestaltung, Seminar June 1960, HfG-AR Ai AZ 564, available via https://hfgulmarchiv.de/quellentexte/fb2864d6654151b783c9c422e5c6bb5f (accessed 02.02.2022)

5. see Otl Aicher, Rede zur eröffnung der Ausstellung “hochschule für gestaltung”, Stuttgart Landesgewerbeamt 26.4.1963 HfG-AR Ai AZ 2062, available via https://hfgulmarchiv.de/ausstellungen/wanderausstellungderhfgstuttgart/9cb430da5c475520b9fa71951dd6a8a3 (accessed 02.02.2022)

6. Letter from Arthur Drexler to William S. Huff, July 1st 1965, Hfg-Arch AI AZ 3244.1, and presented in Exhibition Fever. The “triggered a design revolution” is a reference to a letter from William S. Huff who proposed the MoMA take on the exhibition, Huff was a HfG Ulm graduate and in 1965 Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh.

7. Not uninterestingly, in his letter Drexler implies that much as he admires the design of Braun and Olivetti, he doesn’t consider either of them anything special rather both as reflections of something general …. in 1952 the MoMA had staged an Olivetti exhibition, and although Drexler was a curator in the department at that time Philip Johnson was director. And which, arguably, highlights how the personal positions of those in charge in museums influences what museums show, and thereby how the popular narrative of design and the (hi)story of design is understood See Letter from Arthur Drexler to William S. Huff, July 1st 1965, Hfg-Arch AI AZ 3244.1, and presented in Exhibition Fever.

8. Lilly Reich may be mentioned in some documentation, we just haven’t seen it. Or we’ve missed it, which is always possible

9. Otl Aicher, Ausstellungsgestaltung, Seminar June 1960, HfG-AR Ai AZ 564, available via https://hfgulmarchiv.de/quellentexte/fb2864d6654151b783c9c422e5c6bb5f (accessed 02.02.2022)

10. Otl Aicher, Ausstellungsarchitektur, 1959 HfG-AR Ai AZ 2075, available via https://hfgulmarchiv.de/quellentexte/a8486556ff09589286a4ef9f4b771783 (accessed 02.02.2022)

.

Tagged with: Bauhaus Building, Dessau, HfG Ulm, HfG Ulm: Exhibition Fever, Klaus Wille, Otl Aicher, Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau, Tomás Maldonado, Ulm