"Dear Architect" wrote Maria Chinaglia Ponti in 1967 to the architect, but no relation, Gio Ponti, "why don't you design us some modern furniture? Daddy Walter is worried because our traditional stuff is not selling as it used to".1

An unsolicited request, from a company of whom he'd never heard, an architect of the status of a late 1960s Gio Ponti could have turned down, it wasn't as if a late 1960s Gio Ponti needed the commission; however, something about the letter from Maria Chinaglia Ponti interested, intrigued, Gio Ponti. Beyond the shared surname. For as he continues, in his recounting of the tale, "Ci vado".

"I went to see them".......

Born in Milan on November 18th 1891 we discussed the life and work of Giovanni “Gio” Ponti in a previous post, and so refer you there dear reader for the wider biography, and focus here on the part of that biography centred around events of the late 60s/early 70s, a period when the Grand Doyen of Italian architecture and design was in his late 70s/early 80s, but by no means thinking of retirement: in addition to developing the Denver Art Museum, and realising the façade and piazza for the De Bijenkorf department store in Eindhoven, the late 60s/early 70s also saw Gio Ponti working on his monumental Gran Madre di Dio Co-Cathedral in Taranto, one of the last, and most explicit, embodiments of Gio Ponti's architectural positions. And he still found time, and interest, to travel to the the small village of San Biagio, near Mantua in south-eastern Lombardy where in 1954, after 17 years as part of Fratelli Ponti, Walter Ponti had established his own, eponymous, carpentry workshop and furniture business.

A carpentry workshop whose workmanship, and proprietors, Gio Ponti was taken with, and thus he accepted Maria Chinaglia Ponti's request to design "some modern furniture" for, and with, Walter Ponti.

The first public fruits of the cooperation between Ponti (Gio) and Ponti (Walter) was a bedroom suite presented at Salone Milano 1968, a bedroom suite we've only seen in pictures2 and which for all that it is a very nice example of a simple, functional, rational, contemporary bedroom suite is also otherwise thoroughly inconspicuous. Certainly in context of the wider Gio Ponti canon. And also represents a very reserved interpretation of "modern". And that with good reason: "I was a bit cautious at first", confides Gio Ponti, "it's so easy to make mistakes with modern stuff, and I could have harmed them"3; or as Domus 468 noted it is a bedroom suite developed "with all the precautions, even of economic nature, necessary for the first attempt of an artisan-level industry wishing to embark on modern production".4 Is an expression of Gio Ponti (designer) and Walter Ponti (manufacturer) slowly feeling their ways forward, getting to know one another, developing a relationship, gauging in which direction things could, should, progress.

If both safe in the knowledge that things would progress.

Which, yes, does make the bedroom suite an interesting metaphor.

But before we come to that progression, let's take a brief step backwards. Which, no, isn't a continuation of the metaphor.

In 1966 Domus, that magazine Gio Ponti had established in 1928 and guided until his death in 1979, initiated its own bi-annual furniture fair, Eurodomus; an event which, according to Lucia Frescaroli and Chiara Lecce, rather than being about company's promoting their wares, was "a place where furnishing design and arts can perform a synergetic experience of their practices. Set up by designers, artists, and producers, it's stands abandon their mere commercial function and are transformed into scenic and experimential environments".5 And thus, and for all that Eurodomus may resemble many a contemporary furniture trade fair, represented a relatively new approach to furniture trade fairs at that time. And that not just in terms of how objects were presented, but also why and wherefore they were presented, or as Gio Ponti notes Eurodomus set out to show "realistic designs, produced at a competitive price, the work of trained designers, fulfilling the function for which they were required", and which in contrast to more conventional furniture fairs where people go "full of preconceived ideas - they go almost intending to be deceived", sought to teach visitors to discriminate in their furniture, furnishings and interior design, to think more about their interiors and to move away from "the fake, the commonplace, the imitation, the tinsel glitter, all that which will make their neighbours believe that they are richer than they really are".6

And a new approach to furniture fairs that was accompanied by the launch of Domusricerca, Domus Research, a cooperation between Domus and the manufacturers Arflex and Boffi; a platform established for the purpose of "studying and testing new proposals, new uses of materials, new products and forms of service to the life and house of man, in consideration of both his actual and foreseeable needs".7 And a platform whose first project by Gruppo 1 a.k.a. Cesare Casati, Joe Colombo, Giulio Confalonieri, Enzo Hybsch, Luigi Massoni & Emanuele Ponzio, and thus designers very much of late 60s pop and plastic persuasions - late 60s pop and plastic which help place Gio Ponti's "cautious" 1968 bedroom suite for Walter Ponti very much in context - was presented at Eurodomus 1 in Genova: an "experimental flat for a family of 4/5 persons" and which was defined by the floor plan in which "all the rooms are clustered together in the central part of the area, and surrounded and connected by a perimetral passage. The rooms open on this passage with folding partition walls"8, folding partition walls which allow the rooms to be varied in size as and when required.

Folding partition walls that bring us back to Walter Ponti, Gio Ponti and "modern furniture".

"What matters in a house is not the surface area in square yards, but the amount of space that is "useable", vitally, visually, effectively, with versatility in terms of light, air and variety of purpose"9, opined Gio Ponti in 1970. One secret of achieving such was, so continues Gio Ponti, the use of folding partition walls.

A position and argument that reminds very much of the logic behind Peter Behrens' 1912 Mannesmann-Haus in Düsseldorf and as such reminds of the helix along which architecture and design travels, and a position and argument, and Gruppo 1 project, Gio Ponti advanced and evolved in his so-called La Casa Adatta, the Well-adjusted Home, presented at Eurodomus 3 in Milan in May 1970; a Casa that according to Gio Ponti sought to resolve three contemporary issues: "1) architectural planning as an integral part of the nation's residential needs; 2) industrial participation in the the most well-adjusted procedures; 3) collaboration of the furnishing industry and the great distributing firms for the realization of price structures accessible to all".10

Issue three being approached in La Casa Adatta with furniture objects designed by Gio Ponti and produced by Walter Ponti; furniture objects which had fully discarded, overcome, vanquished, the caution of the 1968 bedroom suite, and that not just formally, but functionally and conceptually.

Furniture objects which, in keeping with the freedom afforded by the folding partition walls, were "designed in order to fit into all living areas, and not just belong to one kind of room"; and objects which additionally contributed to both the free use of space and maximising of the potential of the available space through a rejection of the conventional, static, large tables and armchairs of Italian interiors, and embracing lightweight items "on castors for easy shifting, or foldable, so that spaces can be easily cleared".11

Castors Gio Ponti had previously toyed with in 1968 in a, we suspect never commercially realised, project with Tecno12, specifically a bed and dressing table where the castors are very much a feature of the design, positioned as they are at the bottom of a very prominent, if formally open, chrome-plated steel rod structure. And which, again, helps place Gio Ponti's "cautious" 1968 bedroom suite for Walter Ponti very much in context. In the so-called Apta collection13 for La Casa Adatta the castors are more conceptually important than formally important, and thus (all but) hidden, save on a metal (day)bed which has an air of a hospital bed about it. In a good way.14

An Apta collection for Walter Ponti that also included, amongst other items, a round folding table whose top resounds in brightly coloured patterns, a wardrobe with a swivelling door we don't really understand, but whose playfulness we do enjoy, and a double seated desk where, as with Frank Lloyd Wright's desk for the 1906 Larkin Administration Building in Buffalo, New York, the chairs are attached to the frame and swing in and out. Gio Ponti's interpretation being however a much more sophisticated, refined, visually light object. Is, if one so will, a re-imagining of Lloyd Wright's iron brute for residential spaces, an updating of Lloyd Wright's concept for not only a new location, but also for a new society.

An Apta collection that although of conventional materials is, inarguably, "modern", conceived as it was in context of reflections on the realities of contemporary, and future, domestic arrangements, reflections on the contemporary, and future, economic realities of housing and furnishing, reflections on the realities of contemporary, and future, Italian society.

An Apta collection developed by a designer approaching his 80th birthday, yet who was still motivated and driven by questions of the contemporary and future, by questions of the relevance of his work; by a designer who was always seeking to remain relevant to prevailing realities, while never allowing himself to be distracted and deflected by what others were doing, a designer who explored his own ways forward, and thus a collection that, in many regards, embodies Gio Ponti.

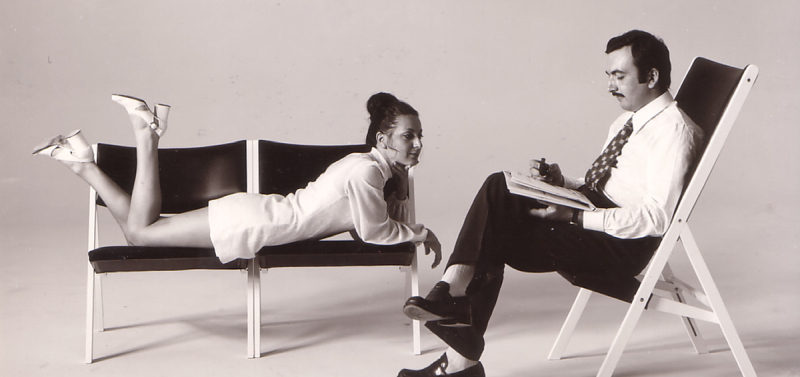

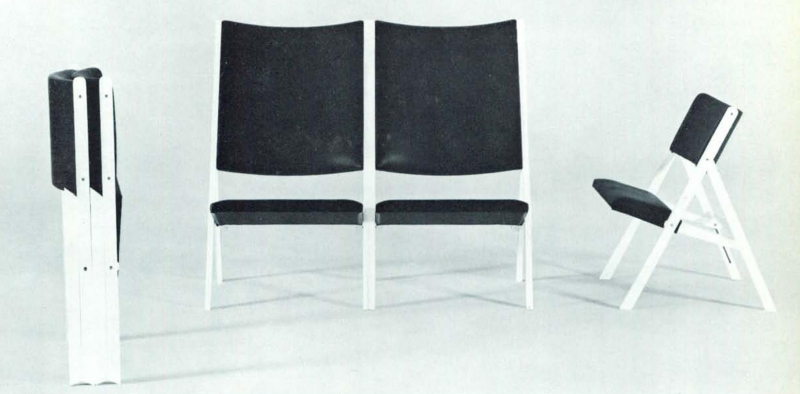

And an Apta collection whose star is and was, inarguably, the Gabriella Chair15. A work that is, we'd argue, Gio Ponti's most important chair design.

Which, yes, is a big claim.

The starting point for the Gabriella Chair was very clearly reflections by Gio Ponti on the act of sitting; specifically the fact that in a conventional chair while one may be able to sit comfortably with both feet on the floor, "you cannot cross your legs though, without slipping forward and using only half the seat".16 And also only using a part of the backrest, the small of your back and the bottom of your spine being unsupported. Or alternatively perching on the front half of the seat and using none of the backrest.

Now, a few of your thinking, that was Gio Ponti's biggest problem in 1970! Crossing your legs while sitting! Niche!

Which on the one hand is fair.

But on the other hand is to ignore that in his analysis of how sitting changes when you change your position, Gio Ponti implicitly questions the accepted conventions of chair design. Asks why do chairs still look the way they did centuries ago? Asks if the chair as universally known and accepted is universally relevant? Asks are there alternative typologies of chairs that would better support specific functional demands? Asks, how responsive are contemporary chair designs for contemporary society, for contemporary sitters?

And surely one of the functions of a furniture designer is to question, analyse, speculate, experiment, and that not just in context of materials and production processes, but in context of the modes of sitting.

And while we need chairs to sit on, for example, at desks, and at dining tables and at dentists, why shouldn't, couldn't, we have chairs that better support and assist us in other seated moments, other seated moments that call for, demand, alternative sitting positions; moments such as, for example, casually sitting at home reading a book/newspaper/magazine or enjoying a glass of wine, good company and animated conversation on the balcony/in the garden, or..... no we'll get to that? How does a chair for sitting comfortably and naturally with crossed legs look?

???

Gio Ponti's very simple solution was to half the size of the seat.

Not only do you not need it all, but having it all restricts your movement and forces you to take up a less than optimal ergonomic position. And requires the use of materials that could be readily saved: the full seat being as economically wasteful as it is functionally unresponsive.

Halving the seat depth is a very simple trick, but astoundingly effective.

Gio Ponti and Walter Ponti presented the Gabriella Chair in two versions, one with a short back and one with a high back, and for us the high-backed version is very much the more engaging, the more meaningful, the more satisfying of the two.

On the one hand on account of the delightful discrepancy between the short seat and long back, which creates a visual tension that irritates and delights in equal measure; and also because the security the high back offers means you can lean back, relax and concentrate on whatever it is your doing in a responsive, supportive environment.

Which makes the Gabriella Chair exactly the sort of seating device we need today.

Or put another way, and to return to where we abruptly stopped above, we'd argue that as a work the Gabriella Chair is a lot more relevant today than it was in the 1970s, that while people sat crossed legged in the 1970s, they didn't use tablets and smartphones and laptops, objects whose use, when not seated at a desk/table, demands when not necessarily crossed legs, although that is in many regards the optimal option, certainly demands the raised knees and leaning backwards the Gabriella Chair positively invites, insists, you to take. And that in a chair with the security of an over-dimensional backrest, a chair which reliably and comfortably and responsively cradles you.

And that not only in the home, but in the office, in the hotel lobby, in the garden, in the airport, in the atelier, in the over-priced artisan coffee roaster, in the wherever. Think of any space in which you sit on a regular basis, add a high-backed Gabriella Chair and that space becomes more inviting, more engaging, more meaningful, more enjoyable. Yet while one can imagine such, one can today on account of the Gabriella Chair's lostness, only imagine such.

Not that the Gabriella Chair is completely lost, certainly not to the extent other objects in this series are lost.

Since Gio Ponti's death in 1979 there have been a couple of re-editions: in 1991 Pallucco released the high-backed version in a limited run of 100 in steel and vinyl leather, a re-working that while not without its charms, misses a very important point of the Gabriella Chair; and in 2014 Molteni&C launched a, as far as we can recall, very short-lived re-edition, of both versions, and in which Gabriella was pitched very much as part of an upholstered interior, part of a conventional Italian interior, something to compliment the large tables and armchairs Gabriella inherently questions, but which are very much Molteni&C's forte. And which, for us, was a mistaken pitch, for while the Gabriella Chair is without question an object for the home, it isn't at home, it isn't at ease, is out of place, as a component of a formal ensemble. Not least because it's a folding chair, it is transient, non-committal, informal; that important point Palluco oversaw in their re-working. In addition the Gabriella Chair is purely about utility, is meant to fit in with your life not your interior, should be part of your home or office or hotel lobby not a component of your furnishing design: and always was, in context of the Apta collection the Gabriella Chair fits much more conceptually than formally. Or put another way, the Gabriella Chair is a tool for contemporary living, be that 1970s contemporary or 2020s contemporary, and is happiest, most relaxed, most engaging and communicative while waiting unobtrusively for its moment. But when that moment comes, it shines. And, for us, does that best in the unassuming dress and self-confident attitude bequeathed by Walter Ponti.

And thus for us, and having never tried the Gabriella Chair as produced by Walter Ponti, the Gabriella Chair as produced by Walter Ponti is, for us, the definitive version.

And that not just because of formal, material and tactile considerations. Not just because Walter Ponti understood the Gabriella Chair.

The exact numbers of Gabriella Chairs Walter Ponti produced and sold is, sadly, lost in the mists of time. But whatever the number is, it is nowhere near that which it should be.

However the numbers are also in many regards irrelevant.

The cooperation with Gio Ponti was, as best we can ascertain, Walter Ponti's only cooperation with a big name architect. Did however help the company achieve a wider visibility than it had previously enjoyed, helped bring in new, modern, clients, and for all allowed the company to enter new markets, and today, as Ermes Ponti, the company is primarily involved with the development, in cooperation with architects, of custom interiors on land and at sea.

In addition, beyond the bedroom suite, the Apta collection, the Gabriella Chair and the increased visibility of Walter Ponti (manufacturer), the cooperation between Ponti (Gio) and Ponti (Walter), led to a strong friendship between Gio Ponti and the Pontis of San Biagio; that 1967 letter from Maria Chinaglia Ponti17 being but the first of a great many letters to flow between San Biagio and Milan, letters, by all accounts, full of warmth and personality, not mundane business letters. And, again by all accounts, Gio Ponti thoroughly enjoyed and relished the time he spent with the Pontis of San Biagio, comparing it with "the good old days of Giordano Chiesa, good old [Egidio] Proserpio, and [Enrico] Monti", craftsman of various ilks who in decades past had helped Gio Ponti realise some of his more interesting and engaging interior and furnishing design ideas, as did, "the dear Cassinas who made chairs, the days that I enjoyed such a long time ago".18

"Days that I enjoyed such a long time ago" in which as Franco Cassina recalls Gio Ponti would turn up at the Cassina factory in Meda on Saturday afternoons to work with the Cassinas and their craftsmen on the development of the Superleggera, that other so essential Gio Ponti chair.19

Sentimental? Yes. Which is the point.

The Gabriella Chair was one of Gio Ponti's last commercially realised furniture designs, a work that is not only formally highly engaging, and highly modern, nor only functionally and conceptually intelligent, and highly modern, nor nor only only a work that in its simplicity, formal reduction, material reduction, visual and physical lightness embodies Gio Ponti, and as with Gio Ponti, has lost none of its charm and relevance over the decades, but is also a work that provides a (possible) answer to the question why a late 1960s Gio Ponti, given his status, and the number of major national and international projects he was working on, and that fact he was in late 70s, travelled to San Biagio to visit a manufacturer he'd never heard of: he didn't need the commission. But he was interested in people, genuinely interested in people, in craftspeople, in artisans, in the products of artisans, in cooperations and relationships with artisans. For all his success one gets the impression Gio Ponti was never that interested in the financial rewards, rather that he was, certainly in context of his furniture design work, primarily interested in the process of creation, and in the people with whom he cooperated, in the people with whom he worked for and with, interested in them as people as much as as partners; and for all was interested in the personal relationships that developed through the creative process. An interest in friendship and community which after five decades of cooperations and projects remained as strong as ever. Personal relationships he never stopped understanding as an important, ¿the key?, component of any project.

Thus the Gabriel Chair helps remind us that for all commercial furniture design is business, it can also be, should be, about personal relationships; that the process of developing new furniture designs, or new interior designs, should be about what the parties get personally, emotionally, from the process as much as about any potential financial returns.

Which is why, we'd argue, the Gabriella Chair is Gio Ponti's most important chair design, embodying as it does not just Gio Ponti (designer) but Gio Ponti (man).

And thus a great lost furniture design classic

1Gio Ponti, East Po River Story, Domus 490, September 1970, page 30 As with all quotes from Domus we use the english as printed rather than our own translations of the original Italian.

2There is, for example, a picture in Domus 468, November 1968 page 35

3Gio Ponti, East Po River Story, Domus 490, September 1970, page 30

4Domus 468, November 1968 page 37

5Lucia Frescaroli and Chiara Lecce, Eurodomus 1966-1972. Una mostra pilota per la storia degli allestimenti italiani, in ricerche di s/confine (Università di Parma), Dossier 4 Esposizioni, 2018 Available via https://www.ricerchedisconfine.info/dossier-4/index.htm (accessed 11.03.2022)

6Gio Ponti, The First Eurodomus Exhibition in Genova, Domus 440, July 1966, page 28-29

7Domus 438, May 1966, page 30

8La Prima Realizzazione di "Domusricerca", Domus 440, July 1966, page 9

9Gio Ponti, More usable space in a smaller area, Domus 490, September 1970, page 24

10Gio Ponti, La Casa Adatta, Domus 488, July 1970, unnumbered page (Domus 488 has no page numbers)

11Gio Ponti, More usable space in a smaller area, Domus 490, September 1970, page 24

12see Domus 463, June 1968, page 45

13see Gio Ponti, More usable space in a smaller area, Domus 490, September 1970, pages 24 - 29

14ibid, page 29

15For the etymology of "Gabriella" Chair see FN 17

16Gio Ponti, East Po River Story, Domus 490, September 1970, page 30

17Although signed by Maria Chinaglia Ponti, the daughter of Walter Ponti and sister of Ermes Ponti, the letter was written by Gabriella Ponti, wife of Ermes Ponti. Many thanks to Daniela Podda, wife of Paolo Ponti, architect and Artistic Director of Ermes Ponti for the clarification. A clarification which also explains the name.

18Gio Ponti, East Po River Story, Domus 490, September 1970, page 30

19see Superleggera: The Chair-Chair in Salvatore Licitra et al, Gio Ponti, TASCHEN Verlag, Cologne, 2021 pages 298 - 301