As the old adage has it, and as (hi)story tends to confirm, we, collectively and individually, often can't see the wood for the trees.

An amblyopia that of late has developed to a, collective and individual, difficultly in seeing both those metaphoric trees and those physical trees. And therefore to a deterioration of the understanding that we exist in a metaphoric and physical wood. With all the inevitable consequences that has, and will continue to have.

With Trees, Time, Architecture. Design in Constant Transformation the Architekturmuseum der TU München provide a space for considerations and reflections on physical trees and woods, and by extrapolation on metaphoric trees and woods.......

Trees were here long before humans. Loooooooooooong before. Which, perhaps, possibly, is the reason humans as a species are so dependent on trees: they not only helped lay the groundwork that enabled humans' arrival, intimately know the vicinity in which we exist, but also have centuries, millennia, more experience of existing on this planet than us, know the aptitudes and tricks required to flourish successfully. Are the sort of knowledgable local it's always good to hang with. Who are intrinsically better to rely on than a guide book or an Instagramer focussing on the next under-the-table, please-don't-tell-the tax-authorities, deal.

A reliance on, a dependence on, trees throughout the (hi)story of the human species, arguably since the days of the earliest proto-human species, discussed in Trees, Time, Architecture. Design in Constant Transformation's opening chapter Trees, Time and People, via themes such as, for example, The Canopy as Habitat, that reality that the earliest humans, and the even earlier proto-humans, lived in trees, and also, as The Tree as Material helps elucidate, lived from trees, lived with tress, from/with living trees, from/with living woodland ecosystems, that over centuries human society had a largely commensalistic relationship with trees/woods, arguably mutualistic, be that in context of for example, the grazing of livestock in forests, one thinks, for example, of the 17th century pigs we all met in context of Re:Generation. Climate change in a natural World Heritage Site – and what we can do about it at Park Sanssouci, Potsdam, that once fed on the acorns under the wild oaks of contemporary Potsdam before the Hohenzollern formalised that natural forest as a private park landscaped to resemble a natural forest, or tanners who once employed bark in their work, or the numerous uses of natural resins amongst near all global communities, before, and somewhat inevitably for all familiar with the path of human society, our latent hang to violence got the upper hand. We got parasitic. And started chopping trees down for our needs at the expense of all other needs: initially for fuel, later for building material. And even later razing swaths of forest for the grazing of livestock.

A shift the chapter Trees and Architecture argues not only wasn't the only option, but isn't the only option in our age of violent industrial monoculture and equally violent 'superfood' t*****. An argument made via a presentation of 30 international projects that provide access to aspects of a variety of active and passive, commensalistic, arguably mutualistic, relationships between trees and human society in context of the built environment that is Trees, Time, Architecture's, and the Architekturmuseum der TU München's, primary focus.

A discussion presented in five themes: Trees in Open Spaces, essentially parks and green urban spaces, including brief discussions on, for example, Parc Henri Matisse in Lille, France, from 1995 or the early 1950s Højstrup Parken in Odense, Denmark; Trees between Architecture; Trees on Architecture; Trees in Architecture; and Trees beside Architecture. Thematic discourses whose prepositions neatly allude to the nature of the relationships between Trees and Architecture in the projects presented. Projects that include, and amongst many others, the traditional Jardinu system of the islanders of Pantelleria, to the west of Sicily, essentially a high stone circle within which a citrus tree grows, thus protected from the hostility of the Mediterranean environment; Frei Otto's Ökohäuser project, his contribution to the 1987 International Building Exhibition, IBA, in West Berlin, an event discussed by and from Anything Goes? Berlin Architecture in the 1980s at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, and Ökohäuser that in not only integrating trees and plants in the structure of the construction, but integrating the existing trees in the concept, and being a participative, self-build project, tends to echo not only the main themes of IBA '87 but also the discussion of Otto's oeuvre in context of Nature, Softness, Transparency, Sustainability, Lightness by and from Beyond Geometry. Frei Otto x Kengo Kuma at the Kunstsammlungen, Chemnitz; the large greenhouse in the botanic garden in Yerevan, Armenia, a structure from 1979 that, having fallen into disrepair, began to be taken over, claimed, by some of the trees it once housed, once contained and restricted, in that they grew through, over and out of the structure. And having began to do so were allowed to, we empowered to, continue to do so in context of a major renovation of the garden's infrastructure. Thus a greenhouse that, among other didactic and metaphoric functions, stands as a reminder of that way nature tends to reclaim the human-built environment. A transiency of the human juxtaposed to a (near) eternity of nature to which we shall return.

Or the ever joyous Haushecken of the Eifel region in extreme western Germany, essentially, house-height beech hedges that traditionally stand beside houses on the exposed plateaus of the Eifel by way of protecting them from the winds and other local climatic singularities, much as the stone Jardinu protect the citrus trees of Pantelleria. A not uninstructive same same but different.

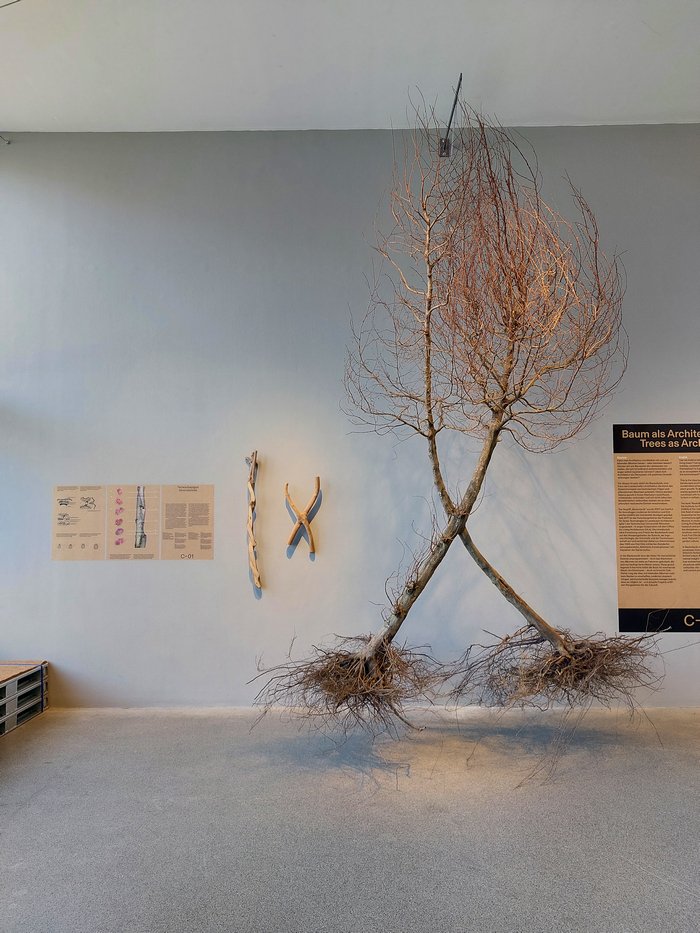

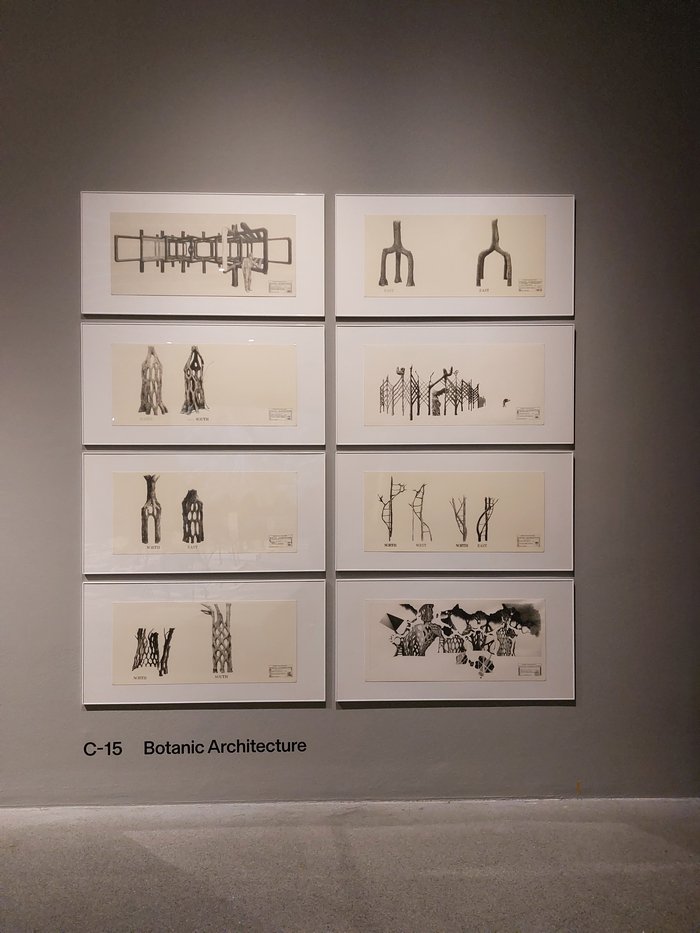

Thoughts on, and examples of, historic and contemporary Trees between/on/in/beside Architecture that in the final chapter become Trees as Architecture.

If one so will, after two chapters exploring wider issues and themes, one arrives at the end of the exhibition at a concentrated discussion on the Trees, the Time and the Architecture of the exhibition title.

A discussion on Trees as Architecture that is less a return to the living in trees of the opening chapter, and of the earliest incarnations of human society, than a documentation of a progression that, and much as with the progression followed in Plastic: Remaking Our World at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, from a peaceful relationship with nature through the commensalistic use of natural occurring materials for plastics, over a parasitic domination of nature as embodied by oil based synthetic plastics, and back to a relationship seeking the peace of yore in contemporary, novel, non-oil based plastic materials, represents a return to behavioural and theoretical foundations of relationships between human society and trees as they once were albeit in context of prevailing contemporary possibilities and appreciations of, and responses, to prevailing contemporary realities, rather than the 1:1 repeating of the past regardless of the now so often demanded, and practised, by those on the right wing of conservative political opinion. Times change, so must our solutions. While remembering the past. Learning from the past.

A discussion, a chapter, based around some 30 international projects represented by models and posters including for example Tongliang Boan Tempel, Taiwan, where in circa 1673 two Chinese fig trees were planted, essentially from principles of religious belief, superstition, but which over the intervening three centuries have grown in number and stature and scale to form a natural roof, supported by (human-built) brick structures, over a public space, over an implied building; the so-called Tree Circus in Scotts Valley, California, a project initiated in the 1920s by Axel Erlandson that sought to actively form growing trees into shapes, specifically rings, knots, hearts, etc that while they may be more decorative than utilitarian, also stand as an early demonstration, or more accurately an early 20th century demonstration, of the possibility of creating structures for human habitation from growing trees. Of an argument against the necessity to kill, dismember and quarter a tree to create a designed and structured building from it. Something echoed in The Edwardes Chair by Full Grown as seen in Plant Fever. Towards a Phyto-centred design at Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden: a living tree grown as a chair. Yes, a living tree that needed to be killed to make the chair accessible, but which save(s/d) a goodly deal of the processing resource use of conventional carpentry and chair production.

Or the Haus der Zukunft, House of the Future, Berlin, a unity of human construction and trees, an example of Baubotanik, that, if it is the building we think it is, which we very much believe it is, bears absolutely no similarly in actuality on the ground in Berlin to that described and presented in Trees, Time, Architecture. Nor, conceivably can it ever do so. Not least because the trees that are central to the project, are the botanik in dialogue with the Bau, aren't sighted on/in the ground in Berlin where they are on the renderings and the model on show in Trees, Time, Architecture. And thus can't do that which they are supposed to. Can't make the Haus der Zukunft the example Trees, Time, Architecture presents it as. Which is perhaps related to the banal realities of Berlin's planning regulations, or the ever present danger of a change of heart on the part of the developer; but also a nice reminder that just because something exists in a museum as a truth doesn't mean it actually is, museums contain mistakes and errors as much as every source of information does. Which is no reason to avoid them, but an admonishment to remember to approach them with care and questions. Similarly these dispatches. We may have gotten this wrong, Don't believe we have. But is something the curators probably should look into. Certainly if Trees, Time, Architecture is going to move on and be shown elsewhere.

In addition Trees as Architecture introduces the living root bridges of Meghalaya, north-east India, those, as the name implies, weavings of living tree roots to bridges, that, as discussed by and from All Hands On: Basketry at the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, not only enable a socially, culturally and economically important, necessary, mobility on the part of the human population of the region, but are an excellent example of the architecture without architects that was not only so important for the rise of the human society, but that can still instruct and inform us today. If we can stop believing the emotive PR-heavy storytelling of contemporary professional architecture.

Thus living root bridges that are also a reminder that architecture is something that became a profession in Europe, after centuries of being practised globally as construction.

A primarily text based presentation, which, as ever, is in no sense a complaint, far from it, we're all for, as we never tire of opining, making museum visitors work, it's the only way they'll take anything from the experience, Trees, Time, Architecture also presents a wide range of photos, sketches and archive documents by way of assisting the unfolding of its narrative. And also presents a large pile of coal briquettes, 16 tonnes of coal briquettes to be precise, one of several artistic inclined interventions that populate and expand the presentation. 16 tonnes of coal briquettes that were once trees. A lot, a lot, more than 16 tonnes of trees.

Thus 16 tonnes of coal briquettes that not only instigate a discussion on if we should be burning coal, a material that, as discussed by and from At the coalface! Design in a post-carbon age at the Centre for Innovation and Design at Grand-Hornu, Hornu, not only has a great many positive applications for human society beyond the fuel human society focuses on, but whose use as fuel impacts negatively on humans and on the environment. The latter reality being discussed in Trees, Time, Architecture by brief mention, not far from the 16 tonnes of coal briquettes, of the protest camps erected and populated by way of seeking to save the Hambacher Forst, an area of ancient woodland that was threatened by the ever expanding Hambach open-cast coal mine next to which it stood/stands. Problems of open-cast coal mines insatiably consuming ever wider areas by way of meeting contemporary global society's demands for a centuries old fuel, also reflected on in At the coalface! in context of the Hambach mine's near-neighbour, Garzweiler open-cast mine, in Joanie Lemercier's film Slow Violence.

And 16 tonnes of coal briquettes formed from a lot, a lot, more than 16 tonnes of trees compressed and anonymised over the millennia, that are also a reminder of just how much longer trees have been on the planet than us, and that thereby allows access to differentiated reflections on the disparity between the temporal scale at which trees exist and the temporal scale at which human society exists.

Or perhaps more accurately, the temporal scale at which human life exists.

For all that on any and every chart depicting the timeline of our shared planet, trees arrive relatively early with a subsequent loooooooooooong gap before we turn up for the last couple of millimetres, invariably breaking things when we do, the traces of human society are long lasting. Certainly relatively long lasting in relation to how long we've been here.

Something neatly elucidated by our buildings and constructions: globally there are innumerable structures, non-natural interventions in the natural landscape by human communities, that have existed for centuries. Buildings, constructions, that over those centuries have, in many cases, continually been repaired, reformed, reconfigured, survived whatever has been thrown at them; elucidations that our built environment is not only in a constant state of development and maturation but that it can be actively re-worked to meet new use scenarios and realities. Can if planned and approached, as a Karl Clauss Dietel demands in context of our objects of daily use, "Nicht für den Tag und baldiges Wegwerfen, sondern für langes Nutzen"1, 'Not for one day and quick disposal, but for long-term use', if they are allowed to, empowered to, develop that Dietelian Gebrauchspatina, patina of use.

A "baldiges Wegwerfen" as an antagonist to "langes Nutzen" that leads to a convincing argument for the necessity to differentiate between the transiency of the individual human life, the temporal scale of human life, and the (near) permanence of human society. A temporal scale of human society that, as the aforementioned greenhouse in Yerevan botanic garden, amongst other examples on show in Trees, Time, Architecture tends to imply, is still (notably) shorter than that of trees, than the loooooooooooong temporal scale of the natural world.

A discrepancy between the time scale of the human individual and the time scale of collective, cumulative, human society that, arguably, is one of those things we're losing an appreciation for through losing sight of trees and by extrapolation the wood. Or put another way, whereas, as Trees, Time, Architecture tends to imply, back in the day we constructed for the time scale of human society, over time we began to architect for the time scale of human life. Our focus has shortened. An argument, arguably, also inherent in Tsuyoshi Tane's Garden House on the Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein. And in the long practised, long conventional, Remove. Rebuild. Repeat approach to architecture, the Rip it up and start again of architects, discussed by and from Demolition Question at the Deutsches Architektur Zentrum, DAZ, Berlin.

A focus on, a primacy off, the scale of human life, arguably, inherent in the hunger of the Hambach and Garzweiler open-cast coal mines and their rapid destruction of that which has taken millennia to form with its inherent, inevitable, impact on that which coming millennia will have the ability to form, its inherent, inevitable, negative impact on coming millennia. ¿Is the contemporary human species unable to think beyond our own direct needs? ¿What if we could? ¿What if we could think beyond our own mortality? ¿What if we could architect analogous to how we once constructed?

¿What if we thought at the temporal scale of a coal briquet rather than that of the flame with which it burns?

Thoughts that set Trees, Time, Architecture in a very pleasing discourse with Monsieur Luftarchitektur – Hans-Walter Müller. Architekt, Ingenieur, Künstler; 1967 bis heute at the Luftmuseum, Amberg: the latter tending to an argument that the transience of human life demands a built environment that is just as transient, if one so will the design in constant transformation of Trees, Time, Architecture's sub-title at the individual scale; the former tending to an argument that for all human society at the individual level is transient it has a permanence at the collective level that demands a built environments that are as permanent, but also resilient to the inevitable changes they will face, not least on account of the individuals in that collective, if one so will, the design in constant transformation of Trees, Time, Architecture's sub-title at the collective scale.

Two temporal scales that we need to find a way to unify not only with each other but with the temporal scale of the tree, of nature. Which is arguably one of the demands of designing human society. A demand generations past didn't need to respond to, that was what they intuitively, instinctively did. But the we do need to respond to. Thus a pneumaticism in Amberg and an arborealism in Munich that for all they can be considered contrary, are, inarguably, both components of formulating the questions we need to approach, allowing as they do discursive takes on permanence, transience and the relationships between the built environment, the natural environment, the human species and the individual human.

Beyond the Architecture of the exhibition title Trees, Time, Architecture also allows for reflections on the (relatively) long lasting trace of human society in context of our contemporary climate emergency, that most palpable consequence of the parasitism and short focussed actions of human society in its most recent incarnation. And that regardless of whether or not you believe in our contemporary climate emergency. It's still true.

Climate change as something exacerbated and advanced by the shift to parasitism, and industrial monoculture, in context of our relationships with trees; but a climate change that, and as a great many of the projects featured in Trees, Time, Architecture discuss, a greater integration of trees in the human built environment, a great setting of trees between/on/in/beside architecture, a greater use of trees as architecture can, could, must, help to minimise, mitigate, but not negate. The latter a discussion point that was very present in Hot Cities. Lessons from Arab Architecture at the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein, and from where we would have discussed it at enormous length had the Vitra Design Museum not pulled the exhibition after Der Spiegel got cross and angry before we could be more constructive on the frustratingly idiosyncratic presentation, having actually engaged with it. Over the course of 7 hours. Rather than getting cross and angry with it. But which nonetheless is a use of trees to create urban spaces as a meaningful, active, response to high ambient temperatures and blazing suns we in Europe can learn from Arab Architecture. We in Europe could learn from Arab Architecture. Much as we in Europe could learn from vernacular, pre-architecture, architecture.

An increasing use, an increasing necessity, of trees in urban spaces in coming decades as a means of countering and responding to the inevitable, unstoppable, consequences of human activity on the non-human environment that, as discussed by and from the aforementioned Re:generation in Potsdam, means we need to start planning, planting, those trees now; the trees we need, need the decades between now and our acute need, to grow.

For all that urgency isn't a word normally employed in context of trees, it is most apposite, essential, for describing the speed at which contemporary urban planning, urban greening, urban treeing, decisions in Europe need to be formulated and realised.

In addition to exploring trees, relationships between arboreal society and human society in context of the Time and Architecture of the title, Trees, Time, Architecture also explores trees, relationships between arboreal society and human society in context of identity, of trees as having a function beyond the physical. A relationship inherent in a great many of the exhibits and discussions, including, for example the aforementioned Haushecken of the Eifel or the root bridges of Meghalaya, arguably also in the collection of photos from across the 20th century collected by Laura Leonelli of girls and women in trees, trees as components of the patriarch females are conventionally, traditionally, excluded from.

And identity that is all too graphically present in the large format photo that stands between the first and second chapters; albeit, and in an act we hope is deliberate for we very much approve of its location, in such a position between the first and second chapters that means you don't really notice it, don't really engage with it, until your on your way back from the end of the final chapter to the entry/exit. Until you've viewed Trees, Time, Architecture and can view the photo both for the photo it is and in context of Trees, Time, Architecture.

A photo that depicts a section of the German Forest, der Deutsche Wald, a romanticised and idealised, and core, component of the German national psyche, of the collective German identity. A Deutsche Wald that in a great many tellings of it since the days of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm is almost a metaphor for Germany. Regardless of what the Germany has variously been since the days of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. A metaphoric wood that can still be popularly seen. And a reminder that much as the aforementioned physical reformation, reconfiguration, re-working of buildings and constructions over time can also be a metaphysical reformation, reconfiguration, re-working of buildings and constructions over time, that the meanings buildings transmit and the associations they mediate are just as liable to variation as their pyhiscal self, so to the meanings and association of the natural world. Such as forests.

A section of the Deutsche Wald, a component of the collective German identity, a piece of Germany, whose entry point is marked by the sign: Juden sind in unsern deutschen Wäldern nicht erwünscht, Jews are not welcome in our German forests.

The photo is from circa 1936. There's a historical context, which doesn't make it any better, doesn't in any sense excuse it, but is important. While beyond the important reminder of 1930s Germany it represents, it is also an all too potent reminder of the darker side of identity. That for all flag waving and song singing is often popularly celebrated, it isn't itself intrinsically positive. Can go rogue. For all the popularly celebrated associations of peoples of all regions with their forests, it isn't in itself intrinsically positive. Can go rogue. And a photo that also stimulates a questioning as to who could find themselves "unwerüscht" in "unsere' deustche Wälder" in the 2030s? ¿Is the Deutsche Wald only for those whose ancestry allows them to 'understand' the deutsche Wald? ¿Is an appreciation for the Deutsche Wald inherited? ¿And if so how many generations must you have within you to appreciate der Deutsche Wald? ¿To appreciate Germany? ¿To be German? ¿What is the temporal scale of nationality? ¿What is the temporal scale of identity?

And a relevance of der Deutsche Wald for the collective German identity, der Deutsche Wald as a metaphor for Germany, that brings one back to our contemporary climate emergency. Specifically via the exhibited cover of an edition of Der Spiegel whose warning/caution Der Wald stirbt, The Forest is Dying — the edition in question is from 1981 thus its primary focus is acid rain, today we can add climate change and, in the case of spruce forests a European spruce bark beetle aided and abetted by climate change and monoculture — causes one to question: what is left of the collective German identity without der Deutsche Wald? ¿What is left of Germany without der Deutsche Wald? ¿What is left of Germany physically and metaphysically without der Deutsche Wald? ¿What is left of us all physically and metaphysically without forests?

¿What is left of us all physically and metaphysically without trees?

Providing as it does for differentiated perspectives on trees, on our relationships with trees, our impact on trees, trees impact on us, our dependence on trees, Trees, Time, Architecture is an engaging and entertaining space in which to not only approach appreciations of human society's relationships with trees past and present, but to approach the myriad roles and functions trees perform in the human environment, trees as also components of the human environment rather than exclusively components of the natural environment we often tend to approach them as. And thus also a meaningful place to begin to approach the myriad questions of human society's future relationship with trees. Of the roles, functions and importance of trees as components of future human society.

And also to reflect on architecture's role and responsibility in such questions. And on the roles, functions and importance of trees as components of architecture past, present and future.

An architecture that, as Trees, Time, Architecture doesn’t directly discuss but does direct one towards appreciations of, hasn't always been sensitive to a natural world it all to often has seen as something both to freely use to meet its ends and to replace, to dominate. Or at least has done since architecture became a profession in Europe. But that as Trees, Time, Architecture allows one to better appreciate, an architecture that can be sensitive to, can work with, nature, trees.

Can. Can work with not from trees. Can learn from Arab Architecture. Can learn from vernacular, pre-architecture, architecture.

A can that if it is to be a 'can' rather than the 'could' it often currently is, requires changes in not only how we build, but how we plan and how we approach the built environment.

Changes Trees, Time, Architecture implies are not only very much possible, but are happening.

Albeit primarily as exceptions to conventional building, conventional planning, conventional architecture, conventional approaches to the built environment.

Exceptions that if they are to move from being thought-provoking exhibits in museum exhibitions to standard daily practice requires moving on from that definition of architecture as an artistic profession for those with a specific training that it has existed as these past centuries. And also requires moving on from the construction of yore. And of appreciating architecture as an active, ongoing component of social processes, as an active, ongoing component of democratic processes, an active process that learns, listens, asks, argues its corner, rather than demanding, dictating, and a process to which we are all empowered to contribute. Of us all as being architects of the local and global spaces and building we populate.

Thus changes in how we build, how we plan, how we approach the built environment that intrinsically involves us all

And whose becoming a norm rather than an exception requires that we all, collectively and individually, lengthen our focus and not only learn to once again see the individual physical and metaphoric trees, but the wood around us, the wood in which we exist, in all its glorious physical and metaphoric complexity.

Trees, Time, Architecture. Design in Constant Transformation is scheduled to run at the Architekturmuseum der TU München, Pinakothek der Moderne, Barer Str. 40, 80333 Munich until Sunday September 14th.

Further details can be found at www.architekturmuseum.de

1Clauss Dietel, Funktionalismus entstand und lebt nur mit Kunst, Form+Zweck, Nr. 6, 1982 pg 35