Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery and on the Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein

“When architecture is born, a place is born” opined Japanese architect Tsuyoshi Tane in 2018, continuing, “humans began to understand that by building architecture, a meaning is given to a place, and then that place has a story that can be passed on to others”.

But for Tane architecture doesn’t just bequeath a place meaning and a story, it also “gives memories to a place”, memories of the past and memories of the future, collective memories that help create bonds. But memories that are increasingly being lost in our complex, high-tempo, contemporary society, with all the inevitable consequences that has for an architecture that must grow organically from itself in unison with society; architecture and society which both need the memories of the past and the memories of future.

Thus, argues Tane, “to create the architecture of a more meaningful further future, perhaps we must … dive in to the past to think of the future, rather than only looking forward”.1

The exhibition Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, and the eponymous Garden House by Tsuyoshi Tane, the latest addition to the Vitra Campus in Weil am Rhein, allow one to approach not only a better appreciation of Tane’s positions but also to experience how they influence and inform his approach, his works, his architecture…….

For all that Vitra is popularly associated with Weil am Rhein, Germany, the company’s origins are to be found just across the border in Switzerland, specifically in Birsfelden on the edge of Basel, the association with Weil am Rhein being first forged in the early 1950s, a period when Vitra was still, primarily, a shop-fitting company, if one taking its first, tentative, steps into domestic interiors alongside retail interiors.

An expansion northwards that was also the start of a building development process that has seen a once rural location on the edge of Weil am Rhein, a space that was once populated by the fields and orchards of small-scale agriculture that define the region, become both the contemporary Vitra Campus with its museums, art works, cafes, salerooms and architecture, and also become a sprawling production, storage and distribution centre for the varied and various Vitra enterprises. Whereby the Vitra head office remains to this day in Birsfelden.

A development process in Weil am Rhein that is one of the opening subjects of Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery; and also where one finds the, if one so will, seeds of the Garden House itself, namely in reflections by Rolf Fehlbaum, Vitra’s ex-CEO, ex-long-serving CEO and that guiding hand without whom the company’s development would have been unthinkable, that while “the industrial idea of taking over nature without caring was very typical for that time”, for all in that period in the second half of the 20th century when Vitra, under Fehlbaum’s guiding hand, was growing to its current stature, “now is the time to rethink nature on the Campus”.2 The first visible expression of that rethink, arguably, being the decision to let the grass around the VitraHaus grow over the summer into a deep, lush, mixed meadow, a genuine joy on a late summer’s day; the first more permanent expressions being the Piet Oudolf Garden and Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House.

A Garden House that the showcase in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery allows one to approach via a series of short texts that move chronologically from the background over the development process and on to the realisation.

Texts supported and backed up by a selection of models, mock-ups, prototypes, etc, including, and amongst many others, numerous conceptual models for the complete house and components thereof, or models of the Garden House in location at various scales by way of helping visualise relationships, or explorations by Tane on creating a door handle without industrial components and which is, in essence, an exercise in basketry, and as such a neat echo of the appreciations enabled by All Hands On: Basketry at the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, of the continuing relevance of basketry in contemporary, and future, society. Or studies for the construction of the rope balustrade for the staircase to the roof-top viewing platform; a viewing platform offering vistas over not just the Oudolf Garden, the architectural highlights at the northern most point of the Vitra complex, or the sprawling production, storage and distribution centre, but also over the fields and orchards and vineyards that still stand opposite the Vitra Campus on the slopes of the Tüllinger Berg, searching, forlornly, for an echo on the plain below. And a viewing platform that was, as one learns, a key component of the process that led to the decision to construct the Garden House. A key component alongside the need for a house for gardeners: both those professional tending the Oudolf Garden and those amateurs tending the Vitra staff vegetable garden.

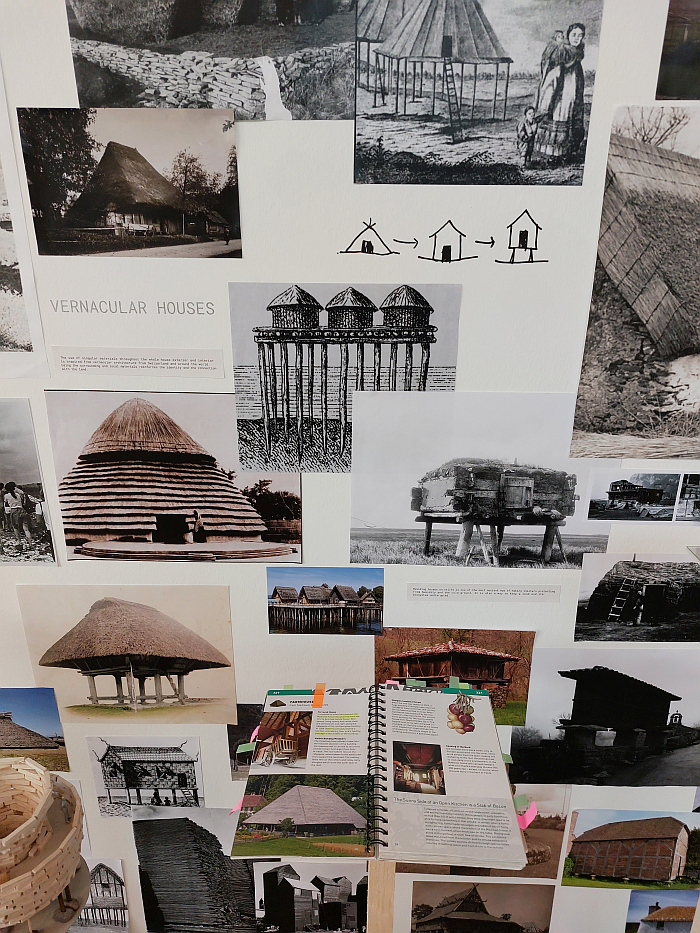

Texts accompanied by an expansive collage of images and statements and questions, which if one takes the time to engage with in detail, which sadly, regrettably, most visitors on the day we were there didn’t, contains a deceptively large amount of information and elucidations both on the conception and development of the physical Garden House and on Tsuyoshi Tane’s positions.

Texts and a collage which elucidate, for example, the importance of Ballenberg in the development of the project and (further development) of Tane’s positions. Ballenberg being an open air museum at the eastern end of the Brienzersee in central Switzerland that is home to over 100 historic rural buildings collected from all corners of Switzerland; a reserve, a repository, if one so will, of rural vernacular Swiss architecture, that in context of the Garden House is and was an important stimulus for reflections on global vernacular architecture, on that, to evoke a Bernard Rudofsky, non-pedigreed architecture without architects, on the “houses of the lesser people” as opposed to the “buildings of, by, and for the privileged — the houses of true and false gods, of merchant princes and princes of the blood”3 that architectural (hi)story primarily concerns itself with. Global vernacular architecture richly celebrated within the collage, and where one notes that a great many of the presented vernacular works are round, and which brings us all back to Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński at the Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław, and the strong implication mediated therein that the houses of the past were round, the houses of the future are round, and we live in quadrats. Why? Or put another way, and with apologies to Tsuyoshi Tane, the memories of the past are round, the memories of the future are round, in our contemporary age where we seek to delegate ever more tasks to, and to isolate ourselves from the world with the aid of, technology, our houses are quadratic. What if they weren’t? Tane’s garden house is (more or less) octagonal, so round with corners. And thus, if one so will, an implication of a move away from that quadratic that European society has, arguably, become stuck in, a move forward back to the future, a move forward back to memories of the future.

A well notated Ballenberg guide book and global vernacular architecture, as seen at Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein

Rural vernacular Swiss architecture that for all it is presented in Ballenberg wildly, decadently, out of context, neither geographically, socially, culturally or functionally in the context it was created, and thus that thing all museums do with their collections, and underscoring that Ballenberg is a museum not a village, does exist in Ballenberg as buildings to be explored, compared and contrasted, as constructions, or as expressions of the relationships between humans and our buildings, between the built environment and the natural environment, or as expressions of the much vaunted form:function correspondence, in which context Rolf Fehlbaum makes note of, learns from, “the appropriateness of these buildings and their interiors”, describing them as works that show “no invention for the sake of novelty but clearly out of necessity” and which for all accept “constraints as a matter of course”, be they constraints, material, climatic, economic, social, whatever. Constraints he believes we need to re-engage with in our complex contemporary age. And also to be explored as expressions, as Fehlbaum opines, of something we’ve “lost”, but what? “A sense of community, respect for an environment that belongs to everybody, a feeling of shelter or being protected?”4 he asks. And in doing so allows one to appreciate “a feeling of shelter or being protected” as being more than a physical act, but something immaterial, something social. Something arising from a “sense of community”. Something, arguably, innate in all animals, something important for the survival of all animals, yet while other species effortlessly master it, the contemporary human animal has lost interest in it. Rejected it. Has sacrificed it for ‘growth’. For a pot of gold at end of a rainbow. And seeks, forlornly, helplessly to replace that ‘feeling’ with an App. Or a snake oil sellers promise of H****.

And an idea of villages of yore possessing a “sense of community” that Rudofsky also understands as a central element of vernacular describing vernacular as a “communal enterprise” rather than “the work of an individual architect”, and also quoting Pietro Belluschi’s definition of “communal architecture” as an architecture, an art, “not produced by a few individuals or specialists but by the spontaneous and continuing activity of a whole people with a common heritage, acting under a community of experience”.5 Thoughts which can also be followed in, approached through, Tsuyoshi Tane’s notion of ‘neighbourhood’, a central theme in the development of the Garden House; and a concept of ‘neighbourhood’ that for all it is physical is for Tane also, ¿primarily?, immaterial, is shared knowledge and experiences, a ‘community of experience’, is that ‘feeling of shelter or being protected’, and is also that which takes on responsibility for the care and maintenance of the buildings in an area. Something that while it, arguably, was an actual thing back in the day when the buildings at Ballenberg stood in their original contexts, is, another, one of things “lost” in contemporary society. How many of us can validly claim to live in a neighbourhood? And an idea of neighbourhood reflected in Tane’s commissioning of local craftsfolks to build the Garden House, of building it from the neighbourhood, of using the neighbourhood not only to create it but to root it in the collective memory of the future. Whereby one must add, comment on, that fact that the thatcher is/was based in Berlin, which barring the fact Berlin isn’t local to Weil am Rhein ……. although, OK, yes, you’re right, there was once a Vitra Design Museum in Berlin, but that’s another story, another memory of the future……. is a deliciously confounding thought: Berlin not being a city known for its endless expanses of thatched roofs, isn’t a city where one can imagine there is much demand for a thatcher. Except at Dalhem Dorf underground station. We’ve since learned that the company have a close association with Spreewald to the east of Berlin, which makes much more sense. But is still an extreme interpretation of neighbourhood. And a focus on local craftsfolks as important in the maintenance of a building, a neighbourhood, a community, a state, our collective memories of the future, that, in may regards, echoes, paraphrases, the opinion of a William Lethaby, that important figure in the move from craft to industry, from Arts and Crafts to more Functionalist Modernist positions, in early 20th century Great Britain, that despite the rise of the machine, despite the inevitability of the coming machine age, we must preserve the handcrafts, otherwise “some day we may wake up to find that the welfare of the nation depends on them”.6 An echo which helps underscore that many of the thoughts, positions and challenges embodied in the Garden House are ones we’ve been at and have faced before, that we currently are at and are facing afresh in new contexts. A reminder that there’s nothing new under the sun, a reminder of a Kaare Klint’s “Problemerne er ikke saa nye, de er i mange Tilfælde løst før”7, ‘the problems are not so new, they have in many cases been solved before’, that we don’t have to invent everything from scratch, a lot of what we need is already here. We just have to learn to see it. Learn to adapt it to our contemporary realities. Learn to look outwith Europe.

A focus on local craftsfolks, a desire to incorporate the neighbourhood in, to strengthen the neighbourhood through, the Garden House, that is also, as one learns through the texts and collage, expressed in the use of what Tane refers to as “above-ground materials” rather than the mined ones more usually employed in contemporary construction, a move, if one so will, away from a Hannah Arendt’s vision of Homo Faber devouring the planet for profit8 towards a more equitable relationship with the planet we all kind of rely on for our existence, a move from exploitation towards that “respect for an environment that belongs to everybody” Fehlbaum (justifiably) fears we have lost. And “above-ground materials” that, in many regards, not all, but many, can also be understood as a further lesson from the experience of looking back at Ballenberg.

Or as Tsuyoshi Tane notes “by experiencing Ballenberg, we realized that we are diminished by the modern global language. We lost the grammar, we forgot the pronunciation, and many vocabularies have been erased”, a linguistic argument that one is more use to hearing from 1960s Italian Radicals than post-1989 creatives. And an argument for a diminishment of our means of communication on account of the dominance of a “modern global language” that tends to focus attention on the local dialects that were such an important feature of inter-War Modernism and the Art Nouveau before it, and indeed vernacular architecture throughout time, local grammatical systems and vocabularies, local pronunciations of global ideals not as a style but as a response to the “constraints” a Rolf Fehlbaum admonishes we focus on. And a linguistic problem, a linguistic impairment, Tsuyoshi Tane sought to counter through a construction process for the Garden House based on “trial and error”, an approach that, in contrast to the “linear” as Tane describes contemporary construction where client, architect, contractor, manufacturers, etc operate independently, saw all actors work as one team, and that no small team, apparently over 100 individuals were involved at various stages. And an approach which echos a Rudofsky’s “communal”, containing as it does elements of a “spontaneous and continuing activity of a whole people … acting under a community of experience”.

And a communality, a community of experience, a neighbourhood, extended beyond the team who created it to include all who use the Garden House, be they gardeners, Vitra staff or visitors to the Vitra Campus.

In which context, yes, you’re right, it’s probably time to leave the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, and wander the short distance to Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House, to move from the theory of Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House to the practice.

Big VitraHaus, Little VitraHaus: Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House and Herzog & de Meuron’s VitraHaus, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein (February 2024)

Big VitraHaus, Little VitraHaus: Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House and Herzog & de Meuron’s VitraHaus, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein (July 2024)

Standing on the edge of the Piet Oudolf Garden and forming one corner of a parallelogram with Jean Prouvé’s 1950s Petrol Station, Kazuo Shinohara’s 1960s Umbrella House and an example of Richard Buckminster Fuller’s 1950s Geodesic Dome concept, the latter another excellent reminder that the houses of the future are invariably round, one of the first things you notice about Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House is that is raised up stilts, a ring of stone slits, so not “above-ground materials”, if materials which keep the rest of the materials safely and securely above, off, the ground. And you also notice, not least because there is no external door handle, only an internal, that Tane’s basketry door handle hasn’t found its place in the Garden House, but may yet still come. We very much hope it does.

The second thing you notice is the thatch, specifically that the thatch isn’t just used for the roof, but also for the walls, a use of thatch that while not common, is known, certainly in the global vernacular, and does conform with Tane’s stated intention to use one material. And while thatch isn’t basketry, that material which gave us our words for walls, it has without question parallels, not least in its global use. And in its contemporary position as something understood as archaic but which is also a memory of the future that “we may wake up to find that the welfare of the nation depends on”. And a material that over time will take on a patina to match, compliment, that which will develop on the Nordic pine of the Blockhaus by Thomas Schütte that stands on the other side of the Oudolf Garden. A patina which while not exactly the Gebrauchspatina, the Patina of Use, of a Karl Clauss Dietel is similar, comparable, as a form, as an expression, of association, of relationship, of function, of memory.

And thatch, and the general focus on the materials in and of the Garden House, that forces one to consider the Garden House in context of the other architectural works on the Vitra Campus, in context of the materials of the other architectural works on the Vitra Campus, be that, for example, the mid-20th century aluminium visions of the Prouvé Petrol Station and Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome, or the cost effective béton brut of Zaha Hadid’s Fire Station and Tadao Ando’s Pavilion or the slightly more reflective brick of Álvaro Siza’s Factory Building and Herzog & de Meuron’s Schaudepot. All, one notes, ‘under-ground materials’. Or the simple wood of Thomas Schütte’s Blockhaus and of the anonymous Beehives. And to do so to approach an appreciation that whatever else the Vitra Campus is, it is also reflections on materials, how we use materials, why we use materials, on the relationships between materials and architecture, on how over the decades and centuries architecture has become as much a practice of materials as one of form or function, and that in doing so the choice of materials has become a statement of intent by architects, a reflection of the hopes and fears of an age, the materials of architecture not just containing memories of the past but memories of the future. And the damage architects can inflict upon us all and the planet we rely on with their choice of materials. And thus also initiating thoughts on the differences between construction as found at Ballenberg and architecture as found on the Vitra Campus, Ballenberg as memories of construction, the Vitra Campus as memories of architecture, and posing the question if an active decision on materials is a central difference, a decisive difference, between architecture and construction? Marks that moment when construction became architecture? ¿And by extrapolation marks the moment when craft became design?

The external water trough of Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein (February 2024)

And the third thing you notice is that it’s not a Garden House but a Garden Shed, which is in no sense an insult or complaint, far from it, is but an observation and for all a clarification of its function. Not far from Tane’s work stands Renzo Piano’s Diogene project, a work that is a house not just because with its prominent gable ends it looks like a house, but because at the core of its conception, development, realisation and raison d’etre is the understanding that people can live in it. For short periods, but can live in it. Tane’s work isn’t meant to be lived in, it is, as noted above, for gardeners professional and amateur, a location for storage, rest and gathering, for community, i.e. a shed. Is meant to occupied and filled with life, but not lived in. Just as a barn isn’t a house, neither is a shed a house. And as a shed we see no reason to doubt its ability to perform its function, see no reason to question its, to paraphrase a Rolf Fehlbaum, “appropriateness”.

And is also meant to be a viewing platform. Which it achieves with aplomb.

As a viewing platform across the Oudolf Garden, a viewing platform across the architectural highlights at the northern most point of the Vitra complex, a viewing platform across the sprawling production, storage and distribution centre, a viewing platform across the fields and orchards and vineyards of the Tüllinger Berg, a viewing platform across the (hi)story of that corner of Weil am Rhein, and also as a viewing platform across the vista of architecture past, present and future, a viewing platform from which to “dive in to the past to think of the future”. And from which to observe George Nelson, an individual in whose company you should always visit the Vitra Campus, being as he is and was that guiding hand in the rise of Herman Miller in the second half of the 20th century and that key figure in the development of Vitra, for all the understandable focus on Eames and Vitra, Nelson is and was in many regards much more important, not least in those early years of development in Weil am Rhein. And a George Nelson who delighted, with that almost childish enthusiasm he extruded, in the Rome he experienced in the early 1930s, a Rome in which you found “three epochs coexisting in one building”9, his (¿theoretical?) example being a 15th century palazzo that had been built around a centuries older arch and one corner of which had recently been turned into a “ultra-modern” candy shop, a Rome that had developed within, throughout, on top of, itself. A Rome that Mussolini, giving free reign his inner Haussmann, his inner Caesar, and his ego, sought to flatten, extinguish, and to replace with mighty boulevards, representative suburbs and monuments. Which although, arguably, isn’t exactly what a Tsuyoshi Tane means with his memories of the past and memories of the future being lost in and to contemporary society, does allow early 1930s Rome to help underscore that we have choices in how we move forward: we can do it cumulatively, maintaining that which we have and adding, incorporating, the new or we can do it successively, sacrificing the old for the new as we move, like a Birsfelden shop-fitter gliding across northern Weil am Rhein. The Garden House is very much not only an appeal for the former, but a series of extended arguments why Tsuyoshi Tane considers the former the better approach.

And also allowing the Garden House to stand as a reminder that for all the future will come, it isn’t a fixed inevitable, we can, we do, influence the future in the now. Or put another way, Finitribe’s ever glorious Forevergreen10 opens with the narrator’s “People used to dream about the future. They thought there was no limit to progress. They dreamed of a clean, bright future, where science would make everything possible, and everybody better off”, whereby the residents of Ballenberg in its myriad original locations didn’t, they knew nothing of such thoughts, had no memories of such a future, rather such thoughts were disseminated, such memories were laid, by the early 20th century Modernists, and taken up with gusto in the middle of that century. Something underscored by the track’s use of “and in warmer seas are new realms of pleasure”, a sample from General Motors’ Futurama II immersive installation at the 1964 World’s Fair,11 the sort of immersive indoctrinating installation in the interests of industry that Nelson, and the Eames, were pivotal in developing and propagating; and a view into the future as imagined, foretold, by American industrialists in which humans had colonised the moon, the Antarctic, and the sea bed, industrially farming the latter and mining its ores and minerals with gay abandon.

In warmer seas there are not ‘new realms of pleasure’, in warmer seas there are the source of the annihilation of all life on earth. Warmer seas are a mid-20th century utopia that has revealed itself as a dystopia. Similarly the felling of vast swathes of tropical rainforest Futurama II celebrates, rainforests felled with lasers one notes. And, and as discussed from Into the Deep. Mines of the Future at the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen, is the mining of the ocean floors for ores and minerals that we’re on the verge of commencing such a good idea? Really? Who says it is? Have we learned nothing from that 20th century fascination with, and decadent overconsumption of, the aluminium that forms the basis of Prouvé’s Petrol Station and Bucky’s domes? Can one view Futurama II today without understanding it as a damming, shaming, indictment of all that we did wrong in that period when as Rolf Fehlbaum notes “the industrial idea of taking over nature without caring” was typical, unquestioned, actively pursued and celebrated? And that in the name of our future.

“But”, as Finitribe’s narrator continues, “somewhere along the line that future got cancelled”. And looking around us today, its easy to agree. But did it? Really? Cancelled? And did a sense of community, respect for an environment that belongs to everybody, a feeling of shelter or being protected really get “lost”? Or have we just fallen into a few pitfalls of our own making, been caught in traps constructed from our egos? Been led onto routes charted by navigators who weren’t guided by the compass of society’s interests? Betrayed ourselves through “only looking forward”. Was the so-called ‘Postmodernists’ complaint with the memory of the Modernist’s future or with the route we were taken there? And is, was, our ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ an appropriate response to those complaints? Bauhaus was a veritable nest of Dadaism, what if we’d taken a Dadaist path, or a Surrealist path, forward rather than an Industrialist? Have we optimised and standardised ourselves into a dead-end? Is there space to turn? Can we get ourselves out of our predicament? Can we learn to ignore that impulse of recent generations to push ever faster ever further forward and recall and employ the varied and various memories of the past and memories future, the good memories and the bad memories? Can we live without flying cars? Can we live without delivery drones? Can we live without making things ever worse for ourselves? Can we live without adding the next failed utopia to Finitribe’s long list and accept we have to exist here with what we’ve got? Can this text find its way back from memories of 1990s Electronic House to the realities of 2020s Garden House?

In his appeal for a rediscovery of “constraints” a Rolf Fehlbaum isn’t, at least in our interpretation, he may see it differently, you’ll have to ask him, we haven’t, but we see in his appeal for a rediscovery of “constraints” not an argument that there are ‘limits to progress’, but rather that that any society has ever changing, ever new, constraints that must be appreciated, understood, respected and within which that progress must be formulated and approached. That which didn’t happen in the second half of the 20th century when we were busily chasing, unconstrained, Futurama II. Or as Forevergreen extols: “We live in the short term, and hope for the best”. The peoples of Ballenberg didn’t live in the short term, they lived in an eternity. An eternity past, an eternity future, an eternity in constant flux. An eternity Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House also occupies. And invites us to rediscover.

An invitation all the easier to accept and to engage with on the one hand because Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House isn’t a memory of the past, such a construction never existed in Weil am Rhein, rather it is an admonishment of the importance and relevance of memories of the past; a difference that helps underscore that for all the ease of reading something of a William Morris’ or a John Ruskin’s return to the Middle Ages as the answer to contemporary ills into the project, it is no mythologising of days past, no caricaturing of days past, rather is a very sober, forward orientated project; a project that contains not only a Rolf Fehlbaum’s observation from experiencing the past permanently preserved in Ballenberg that “life was hard and it would be an injustice to romanticize it”, but also his sage opinion that the remedy to contemporary ills “is not a return to the traditional city or village”. For it ain’t. Nor is it flying cars and delivery drones. And also contains the warnings of a William Lethaby about returning to past forms, about architecture (and urban planning), “diverted and maimed and caged into formulas which are not only dead, but never had life”12, and his insistence that architecture “must be a living, progressive, structural art, always readjusting itself to changing conditions of time and place. If it is true it must ever be new. This, however, not with a willed novelty, which is as bad as, or worse than, trivial antiquarianism, but by response to force majeure.”13 Or in this case force industrie. Force égoïste. Force Futurama II.

And on the other hand, because it isn’t vernacular. And in any case a truly vernacular architecture isn’t possible on the Vitra Campus. As with Ballenberg the Vitra Campus is a curated space. For all that the Vitra Campus is the cultural counterweight to the commerce of Vitra, it is still an artificial construct. For all that the individual components, and in contrast to Ballenberg, exist in context, for all that it may be a village, it is still an artificial construct. Just as any garden is. Including Piet Oudolf’s. Something brutally underscored by a photo in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery of the planting out of the garden. A monstrous job. In all senses of the phrase. For all that the Oudolf Garden is composed of natural materials, it is an artificial construct. As is Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House. There is way too much thought and questioning and discussion and position and argument within it to make it vernacular. Way too much thought and questioning and discussion and position and argument within it to make it construction. It is architecture. And in its thought and questioning and discussion and position and argument helps one approach a further possible difference between architecture and construction, tending as it does to imply that for all architecture is form and function and material it is also theory, arguably today is primarily theory. ¿Theory that marks that moment when construction became architecture? ¿Theory that makes architecture as relevant to contemporary society as construction was for society past?

Yet despite being neither vernacular nor a real memory of the past, ¿precisely because it isn’t vernacular or real past?, it is very much a reminder of why vernacular shouldn’t be ignored, the dangers of concentrating on “the houses of true and false gods, of merchant princes and princes of the blood”, and why “only looking forward” is too simple, that we must always move forward with a view backwards, move forwards with that learned along the way, with the lessons of (hi)story, and with the memories of the past. If not necessarily with the actual past. There is an important difference.

The Piet Oudolf Garden as viewed from the VitraHaus, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein (February 2024) (Views of the Oudolf Garden at other times can be found in context of our post from Garden Futures. Designing with Nature)

The Piet Oudolf Garden as viewed from the VitraHaus, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein (July 2024) (Views of the Oudolf Garden at other times can be found in context of our post from Garden Futures. Designing with Nature)

If we’re correctly informed, which isn’t always the case, Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House is potentially the last building on the Vitra Campus, which obviously it can’t be as the Vitra Hotel still isn’t there, and until it is the Vitra Campus is incomplete.

But whether it is or isn’t the last building on the Vitra Campus Tsuyoshi Tane notes that the Garden House is the first building on the Vitra Campus “emerging from a full awareness of the climate crisis”.14 And while, yes, one could, should, question if Vitra could have, should have, gotten there, here, before the 2020 when the project began, there hasn’t actually been a great many new new buildings on the Campus of late, thus the Garden House was arguably the first opportunity; and in any case there is a much stronger, and much more urgent, argument to be made that what is important is not when Vitra started planning “from a full awareness of the climate crisis” but that they continue to plan from that awareness. That they continue to “rethink nature on the Campus”.

And not just on the Campus; while we fully appreciate the very clear legal and financial distinctions between the various institutions who inhabit the Vitra Campus, it is all a component of the development since the 1950s of that one time Birsfelden shop-fitter, and thus the “rethink” needs to be across all aspects of ‘Vitra’, in all expressions of ‘Vitra’. A rethink that is underway, Vitra, for example, having committed themselves to achieving a series of environmental and social ‘goals’ by 2030, or at least by 2030 in German, in English there are no firm dates, and are also in an ongoing process of introducing more sustainable materials, most recently launching the Eames Plastic Chairs in a recycled, and 100% recyclable, synthetic plastic, and thus moving that most popularly known ‘Vitra’ product away from the fibreglass of the 1950s that for all it was, as with aluminium, novel and futuristic and democratic is and was in its unconstrained use an excellent example of that uncaring, careless, Futurama II, manner in which we all moved forward through the second half of the 20th century.15 As is aluminium. And thus a move away that is symbolic of moves we all need to make. But there is still an awful lot of work to be done; or to evoke Tsuyoshi Tane’s comment in the exhibition, “the completion of the building is not an ending. It is important to main it and to ensure its longevity”.16 And that not just in terms of production but, and as noted in context of Edition 33’s showcase at Passagen Interior Design Week Cologne 2024, how furniture is marketed, distributed and sold is every bit a component of its footprint as how it is produced and from what it is produced. Similarly how an exhibition is produced, marketed, presented, sold and shipped round the world. And thoughts that also move far beyond the Vitra Campus to encapsulate all ‘Vitra’s’ partners, suppliers and dealers. Furniture, interiors and exhibitions can be selfish, dirty, egoistic, businesses. Almost as selfish, dirty and egoistic as architecture.

And while the Garden House may not directly help in all those processes it does stand as an unignorable monument to the moment when that “rethink” was born on the Vitra Campus, to that moment when the Vitra Campus was re-born, and for all contains within it a meaning that can be passed on to others, and embodies hope in “a more meaningful further future”. While reminding that how that future is defined, and how that future is approached, is up to us all, individually and collectively.

Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House is scheduled to run in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Charles-Eames-Str. 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday April 21st.

Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House can be explored and engaged with everyday on the Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein.

Full details can be found at www.design-museum.de and www.vitra.com/campus

In addition an accompanying publication is available. Which we haven’t seen, but fully intend to.

Experiments in rope tying, as seen at Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein

Considerations on neighbourhood, as seen at Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein

The view across the Piet Oudolf Garden from Tsuyoshi Tane’s Garden House to Herzog & de Meuron’s VitraHaus, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein (February 2024)

Two buildings for gardeners: beehives by annonymous and The Garden House by Tsuyoshi Tane, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein (February 2024)

1. see Tsuyoshi Tane, Archaeology of the future, TOTO, Tokyo, 2018

2. Rolf Fehlbaum, quoted in the exhibition Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House

3. see Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture Without Architects. A short introduction to non-pedigreed architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1964

4. Rolf Fehlbaum, Ballenberg? in Rolf Fehlbaum [Ed.] A Way of Life. Notes on Ballenberg, Lars Müller Publishers, Zürich, 2023

5. Pietro Belluschi quoted in Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture Without Architects but sadly not referenced. Always reference your quotes, because the context in which they are made is also important and you must allow others the opportunity to assess the relevance or otherwise independently.

6. William Lethaby, The Foundation in Labour, originally published in Highway, March 1917, reprinted in W. R. Lethaby, Form in civilization. Collected papers on art & labour, Oxford University Press, London, 1922

7. Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 203

8. see Hannah Arendt, Labor, Work, Action, speech presented at the conference Christianity and Economic Man: Moral Decisions in an Affluent Society, Divinity School, University of Chicago, November 10th 1964, reprinted in S. J. James and W. Bernauer [Eds], Amor Mundi. Explorations in the Faith and Thought of Hannah Arendt, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1987

9. George Nelson, Peak Experiences and the Creative Arts, Mobilia 265/66, 1977

10. To be found on the 1992 album An Unexpected Groovy Treat, (One Little Indian, TPLP 34) and on various 12 inches, and also available in innumerable mixes, whereby for us Justin Robertson’s Forevemost Excellent very much is

11. There is no official video available, something General Motors are probably absolutely delighted about, how are they going to sell us flying cars if we all understand the problems their visions have brought upon us all? However, if you search GM Futurama II 1964 on most popular video sharing platforms, especially on that platform, you’ll find some

12. William Lethaby, Modern German architecture and what we may learn from it, speech to The Architectural Association, London, January 1915, reprinted in W. R. Lethaby, Form in civilization. Collected papers on art & labour, Oxford University Press, London, 1922

13. William Lethaby, Architecture as form in civilization, originally published in The London Mercury, 1920, reprinted in W. R. Lethaby, Form in civilization. Collected papers on art & labour, Oxford University Press, London, 1922

14. Tsuyoshi Tane, quoted in the exhibition Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House

15. The new Vitra Polypropylene RE does contain a minimal amount of fibreglass, by way of ensuring structural stability. Is however, according to Vitra, 100% recyclable. And thus a welcome move away from the original Eames’ S and A shells. And in many regards, as with so much in life, be that flying, consumerism, social media or beer, or crisps, it’s not about whether you do it or not, but how often, when, where, wherefore and if you’re actively looking for alternatives…….

16. Tsuyoshi Tane, quoted in the exhibition Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House

Tagged with: Garden, Rolf Fehlbaum, The Garden House, Tsuyoshi Tane, Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House, vitra campus, Vitra Design Museum, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein