Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński at the Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

“Projektowanie i realizacja form powłokowych jest problemem złożony”, opined the Polish architect Witold Lipiński in 1978, “design and implementation of shell structures is a complex problem”. And it certainly is. For all a complex mathematical problem, and that of a degree that, for Lipiński, for all when combined with the associated technical challenges, “greatly limit[s] plastic ingenuity”, meaning as it did that architects were invariably restricted to forms “mathematically defined in a straightforward manner”, which employed but “the simplest elements of translational and rotational surfaces” and “supports of the least complexity”.

“Nevertheless”, he continued, unperturbed, “by juxtaposing sections of these surfaces and variously shaping the supports, a considerable number of architecture forms are obtained”.1

With the showcase Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński the Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław, allow one to appreciate how Witold Lipiński used his appreciations of, his application of, his approach to, his juxtapositions of, geometry to propose new spatial possibilities. And to push the borders of “plastic ingenuity”…….

Born in the rural hamlet of Kosaki, near Białystok, in north eastern Poland on November 14th 1923, Witold Lipiński’s earliest years are still to be authoritatively catalogued; however, what is known is that when in autumn 1939 Germany invaded Poland, triggering the start of the War, Lipiński, then aged just 15, joined the Polish Underground resistance, serving the majority of the War in the unit of, and as a close associate of, Major Jan Tabortowski; a unit of the Polish Underground who were based in the Biebrza Marshes to the north west of Białystok and from where they undertook numerous highly regarded, and still popularly celebrated, actions. Lipiński, by all accounts, being at the forefront of much of the planning and realisation.

In 1946 Witold Lipiński ’emerged’, if one so will, from the Underground in the Biebrza Marshes and moved to Wrocław where he enrolled to study architecture at the city’s University of Science and Technology, graduating in 1950 and the following year joining the faculty’s teaching staff, where he remained until his retirement in 1994. And where he undertook research in a number of varying and varied fields; research which saw him awarded a PhD in 1956 with the thesis Zastosowanie płomieniowych natrysków szkliw ceramicznych do barwnych powłok w architekturze, Application of flame sprayed ceramic glazes for coloured coatings in architecture, which sounds like a misleadingly inaccurate translation on our part, we’re sure you can do better, and achieve his Habilitation in 1979 for his work Powłokowe formy sklepione, Vaulted Shell Forms. Parallel to his wide ranging theoretical work Witold Lipiński was also a practising architect, realising over the six decades of his career both his own projects for private and commercial clients and also contributing to civic projects in context of the official post-War rebuilding and regeneration of Wrocław.

In addition to his academic and architectural work Witold Lipiński, in many regards, also continued in Wrocław the resistance to totalitarian regimes he had so diligently practised in the 1939-1945 War, albeit no longer in the underground; rather serving as Chairman of the Solidarność group within the Faculty of Architecture from 1980 until 1993.

Witold Lipiński died in Wrocław on June 23rd 2005, aged 81.

As an exhibition Shape of Dreams is, in effect two showcases inter-twinned with, and in dialogue with, one another.

The first, a showcase based on Witold Lipiński’s Habilitation thesis Powłokowe formy sklepione, and for all on his reflections therein on 3D geometry, reflections on 3D spaces, reflections on, for example, Simple Cylindrical Forms, as exemplified by the parabolic half-cylinder; Cylindrical Barrel Forms, both concave and convex barrels; Centrally Folded Forms, essentially undulating structures of various types. Or what Lipiński refers to as Formy swobodne i dowolne, Free and Arbitrary Forms, forms he describes as being unknown in geometry but very much known in nature, naming “crustaceans, starfish, shells, flower petals, fruit shells” as examples, and while he opines that such forms are not fully understood, he argues that, in context of their construction, “nature makes very deliberate and rational use of the material, which is fully adapted to the role and tasks of the form as a whole”.2

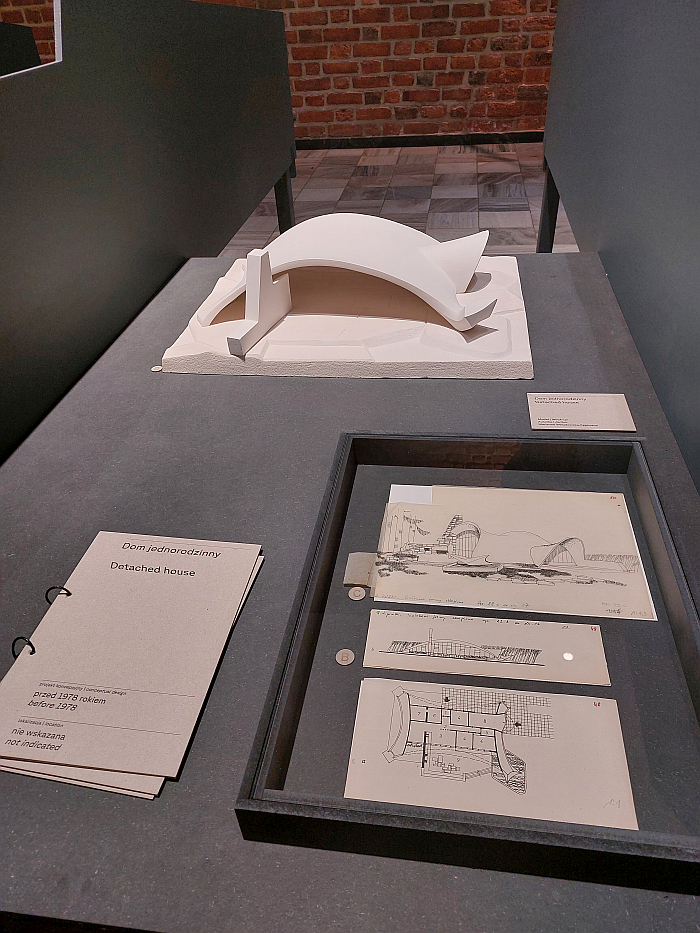

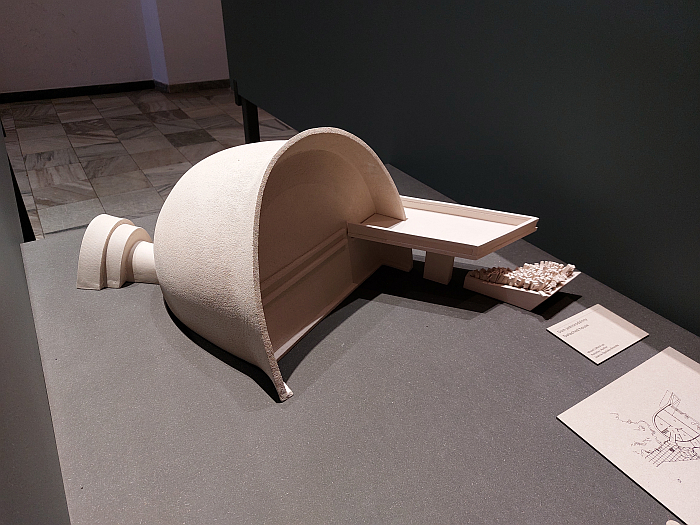

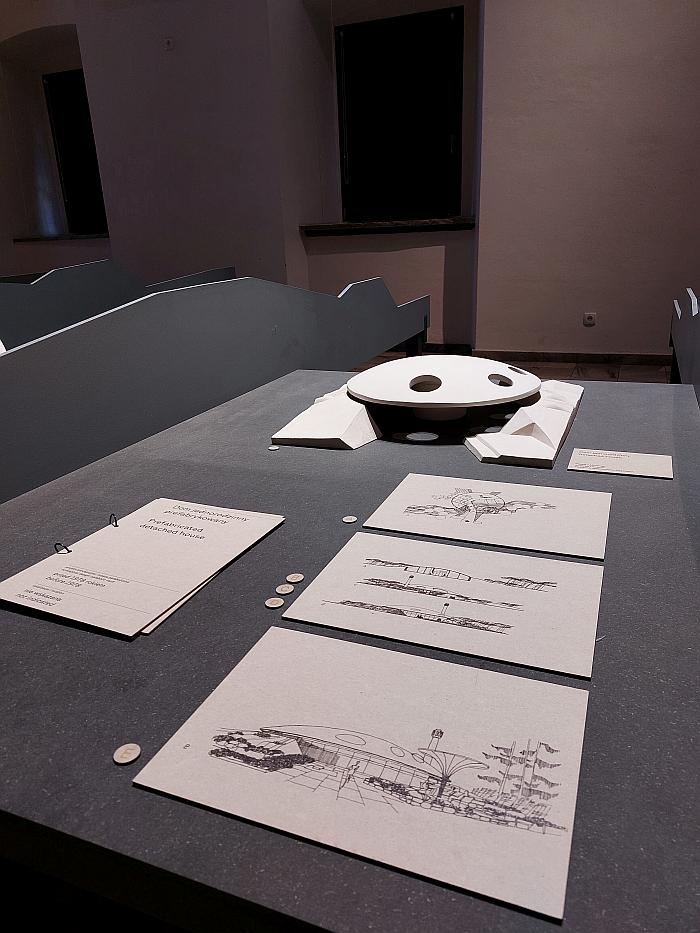

The second, a showcase, a presentation, of some 16 projects, 16 vaulted shell form projects, developed by Witold Lipiński in the 1960s and 1970s, both realised and unrealised. A showcase, a presentation, that in addition to popularly known projects, or perhaps more accurately, in addition to his most popularly if not necessarily widely known projects, such as, for example, the late 1960s meteorological observatory, and restaurant, on top of Śnieżka, the highest peak of the Karkonosze mountain range that forms (part of) the Polish-Czech border, or his own house, his own igloo, in eastern Wrocław, also includes lesser known, lesser seen, works, including, for example, an undated, but pre-1978, plan for a florist kiosk composed of an implied wave combined with cylindrical sections; a, similarly undated, plan for a yacht club complex based around three cylindrical sections bracing one another to form the side walls and roof with expansive curtain wall facades at either end; or a detached house realised between 1963 and 1965 not far from his own house, his own igloo, in eastern Wrocław, comprising, essentially, two differently scaled barrels transitioning into one another with a third barrel attached perpendicularly by way of an entrance and garage. And a work which, one learns, was and is popularly known as ‘Mir’ by locals, after the (former) Russian space station.

And while bearing no actual physical resemblance to the actual Mir space station, it is arguably more resemblant of a Hobbit House, and while it was realised some 20 years before the actual Mir space station, its association, through the inaccurate naming, with space and science fiction is very evocative of the period of its genesis, a period in which space and science fiction were ubiquitous, almost compulsory, influences in all genres of cultural expression and practice.

Including in that of Witold Lipiński.

A flower kiosk proposal (centre) by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

The most obvious example of that highly contemporaneous influence being, without question, the Śnieżka observatory complex, a composition based around three discs, three flying saucers, stacked eccentrically, as in non-concentrically rather than weirdly, the stack is very logical; three flying saucers stacked, floating, eccentrically above Śnieżka as if in a holding pattern before launching an attack on the valley below. ¿But will they attack Poland or the Czech Republic? ¿Both? Śnieżka flying saucers that in Shape of Dreams can also be reflected on and considered in context of two undated, unrealised, house projects: one envisaged as a disc supported by the surrounding landscape, as if a flying saucer had landed in a hollow slightly smaller than it, and which thus shielded the accommodation unit from public view, the other featuring a circular building supported by a slender central column, a work that very much resembles a flying saucer hovering over the garden. And the latter a work that very much, as in very much, reminds of Arne Jacobsen and Flemming Lassen’s 1929 Fremtidens Hus, House of the Future, albeit without Jacobsen and Lassen’s landing pad on the roof for the occupants’ vertical take off and landing aircraft. But then Lipiński’s house was a flying saucer. Transport and accommodation in one. Times change. But as one can appreciate through the comparison of Jacobsen and Lassen with Lipiński, visions of the future don’t necessarily change. In the future houses are circular. Always were and always will be.

And a Śnieżka observatory complex that, as one learns in Shape of Dreams, wasn’t just inspired by space and science fiction, but was also inspired and informed by the location: on the one hand, if your placing a building on top of a mountain the romanticised alpine huts, with their large gable ends, as favoured by generations past make only little sense, exposed as they are to the elements; rather an aerodynamically profiled construction is much better placed to withstand the winds that will inevitably buffet it. Or put another way, for all the actively practised resistance of his political and civic life, with the Śnieżka observatory Witold Lipiński sought an absolute minimum of resistance. And on the other hand the Śnieżka complex was inspired by, as Lipiński notes, “idee strukturalno-plastyczne zapożyczone spietrzonych elipsoidalnych grup skalnych uformowanych erozja, charakterystycznych dla Karkonsoszy”3, ‘Structural and plastic ideas borrowed from piled-up ellipsoidal rock groups formed by erosion, characteristic of the Karkonosze’. Rock groups formed by the winds and rains that regularly visit such an exposed peak: and thus an attempt by Lipiński to not only place the work in context of and in discourse with its setting, but to embed it in the natural environment in which it was being placed, to make it as far as possible a component of that environment rather than an addition to. Or as Lipiński’s 1975 article on Śnieżka is titled: Decyduje Pejzaż. The Landscape Decides.

A hovering flying saucer house, and a re-imagining by Witold Lipiński, of Arne Jacobsen and Flemming Lassen’s 1929 Fremtidens Hus, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

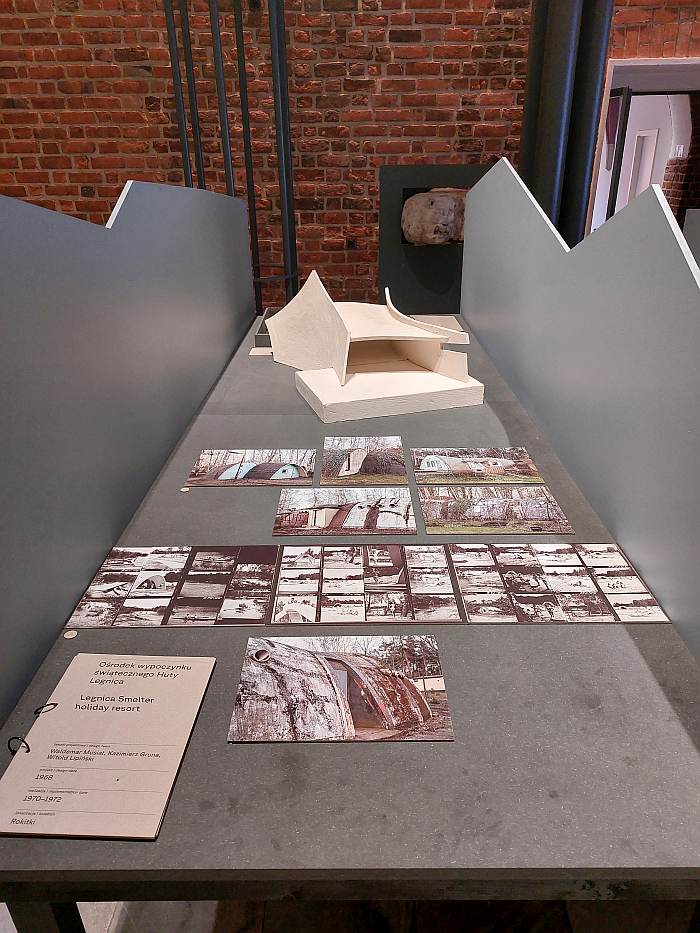

A decision making process left to the landscape that can be further followed and understood in Shape of Dreams via both an undated, unrealised, plan for a mountain shelter, a convex barrel structure that, again, very much resembles a large rock flattened to an aerodynamic form by the ravages of time and weather, and which, again, questions, why we build urban houses on mountains. And also in Lipiński’s late 1960s holiday resort for the workers of the Legnica copper smelter; a project, a village, set in a forest beside a lake in Rokitki to the north west of Legnica, and thus far removed from, and hopefully upwind of, the smelter, that very much echoes the Hobbit House he placed in eastern Wrocław. Albeit as an integrated urban planning concept rather than an individual house. And a Hobbit Village that less seeks to hide in the forest as to be one with the forest. As any good Hobbit would wish to be.

And a decision making process left to the landscape that can also, in many regards, be followed and understood in the house Lipiński realised in the early 1970s for one Bolesław Jahn at the junction of Wyścigowa and Turniejowa in south-west Wrocław, a triangular plot on which, as one learns in Shape of Dreams, Jahn was granted permission to build on condition he didn’t realise a quadratic structure, clashing as that would with the triangular plot. Which sounds like enlightened, insightful, planning decisions in 1970s Wrocław. Thus, while the chance that a Witold Lipiński, certainly an early 1970s Witold Lipiński, would build something quadratic was in any case slim: he was now officially banned from developing a quadratic box. And realised an asymmetrical ellipsoid structure raised up on stilts which has, in effect, been sliced through at one end to create a curtain wall that leads on to a veranda and further on into the garden, a borderless movement from interior to exterior that unites the two as components of a whole. And a work that is popularly known in Wrocław as the ‘Mushroom’, despite, and much as ‘Mir’ doesn’t look like Mir, not resembling a mushroom. Which is in no way a criticism of the citizens of Wrocław; but is to question their understandings of Mir and mushrooms. Rather it resembles a rock, a large rock around which the city authorities have been obliged to bend their roads, thereby implying the landscape decided, implying the city as a cooperation between the human world and the natural world, rather than the imposition and assault on the natural world it actually is. A very nice piece of deception. And a very nice example of Witold Lipiński assimilating his works with their environment. Of the role of nature in Witold Lipiński’s work.

Images of the Legnica smelter holiday village, Rokitki, and a model of a proposed yacht club complex by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

Presenting itself as a mix of photos, plans and models supported by brief, succinct, easily comprehensible, bilingual Polish/English texts authored by both the curators and by Witold Lipiński, Shape of Dreams not only allows for an introduction to Witold Lipiński, or perhaps more accurately an introduction to a 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński, in context of his long and varied career Shape of Dreams is but a snapshot of a moment and no expansive retrospective, which isn’t a criticism, just an observation and an important aspect to be remembered while viewing, and a unequivocal indication that a much larger Witold Lipiński exhibition is out there, waiting to be realised……. Shape of Dreams not only allows for an a introduction to a 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński, but also allows ample opportunity to reflect on and consider 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński in context of those many other architects and engineers and designers who worked with and in Powłokowe formy sklepione, including, and amongst many others, Ulrich Müther, a contemporary of Lipiński who also very much sought to allow his works to communicate with their immediate environment; a Iannis Xenakis whose 1958 Philips Pavilion so elegantly employs music, that shaper of the intangible space, to overcome, sidestep, the mathematical challenges of shaping tangible spaces; a Le Corbusier, that one time colleague of Xenakis, and an architect who for all he is known for quadratic works wasn’t adverse to curves, swings and barrel sections, nor the stilts that Lipiński so often employed; a Yrjö Kukkapuro who planned his late 1960s thin-walled shell home/studio in Kauniainen, near Helsinki, in fibreglass before being forced to revert to concrete; or a Pier Luigi Nervi, an architect from a previous generation but whose work was very much rooted in an ongoing discourse between the problems of mathematics and the demands of the designer, of working with rather than against mathematics in questions of “plastic ingenuity”. And also a Richard Plüddemann whose Hala Targowa, a work realised in downtown Wrocław between 1906 and 1908, represents one of the earliest examples of using a reinforced concrete skeleton to solve the complex problems of vaulted forms.

A Hala Targowa that is just one of numerous buildings in Wrocław that express and elucidate the long (hi)story of work on vaulted forms: quite aside from the many ancient church buildings in the city, including the (long since demolished) 12th century Benedictine Abbey that once stood on the site of the Muzeum Architektury and whose remnants are displayed in the Romanesque Hall that hosts Shape of Dreams, including a section of a sandstone archivolt which towers over Shape of Dreams as if reminding visitors that vaulted forms weren’t a novel 1960s phenomenon, just considerations on their form and span and materials were, one can, must, also make note of the barrel formed 19th century ticket hall of the city’s main railway station, a steel and glass framed space whose juxtaposing with the historicism of the entrance building very much announces the changing times arriving with the age of steam (trains), or, the Hala Stulecia by Max Berg from 1911-1913 with its 69m diameter, 42m high, dome, a work that, inarguably, is the most popularly know symbol of Wrocław. Apart that is from the accursed dwarves, a community that for all they once stood for a utterly joyous and inspired form of peaceful underground resistance have since become representatives of a cheap, lazy, and particularly desperate, form of city marketing.

Plans for and models of the Power Engineers’ Clubs in Bogatynia and Zgorzelec by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

And a Hala Targowa whose expanses of reinforced concrete also reminds that Shape of Dreams ventures but briefly into the materials and construction processes of Witold Lipiński. They are there, mention is made, for example, of his arguments for prefabrication, a process also favoured by a Pier Luigi Nervi, an Ulrich Müther in contrast preferentially employing the shotcrete, sprayed concrete, process, and also noting that his own house, his own igloo, was a brick construction, and thus a very classic dome construction, was, if one so will, a dome akin to the archivolt that towers above Shape of Dreams. But otherwise the materials and process are largely absent. Which is, we’d argue a shame, not least because, on the one hand, in Powłokowe formy sklepione Lipiński tends to imply that the technical challenges are on a par with the mathematical, and therefore his approach to both needs to be discussed together, being as they are components of a inseparable process, and on the other hand because of the very strong links to and referencing of nature in his work, including his opinion that “natura jednak bardzo celowo i racjonalnie wykorzystuje tworzywo”, “nature makes very deliberate and rational use of the material”.4 And it is, we’d argue, important to approach better appreciations of how Witold Lipiński made use of material, how he adapted materials to the role and tasks of the form, how he learned from nature to use materials racjonalnie, by way of approaching better appreciations of not only the work of Witold Lipiński but the legacy of Witold Lipiński.

Not that such detracts from Shape of Dreams, it doesn’t; but does tend to underscore that Shape of Dreams is but an introduction to 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński, a place in which to gain orientation before moving on to further research and exploration.

Further research and exploration you can then begin to undertake immediately after viewing Shape of Dreams on the streets of Wrocław: the presence of three interesting, important and informative Witold Lipiński works in the city being a very easily accepted invitation to experience in the flesh that which you have discovered in theory. That ever present joy of any architecture exhibition concerned with the city in which it is being staged, that chance to explore architecture at the architectural scale rather than the museal.

A concave barrel vault house proposal by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

And when you do visit the three Wrocław projects you better appreciate the contexts of their setting, can understand, for example just how well, how appropriately, how effortlessly, the ‘Mushroom’ sits at the junction of Wyścigowa and Turniejowa, how elegantly it fits into the space, something that can also be seen above, for example through Google Maps. And also to appreciate the outrageous affront of the advertising hoarding placed directly in front of it to not only the work, its architect, and the client who had the foresight to commission it, but also to what it can teach us all about about architecture and urban planning. An advertising hoarding that in many regards stands symbolic of the dominance of commerce over culture in contemporary society. Don’t learn, consume!

And site visits that also allow one to appreciate how thoroughly inappropriately both Lipiński’s own house, his own igloo, and the nearby ‘Mir’ fit into their environment, the igloo and ‘Mir’ as examples of Lipiński not seeking to assimilate works in their environment. An ill fit that is however, arguably, deliberate, a deliberate provocation, standing as they both do in a very green, spacious, suburb of Wrocław, a suburb that, one very much gets the impression, was a well-to-do part of the city in the 1960s and 70s, as it almost certainly was before and may have remained since. And a quiet, traditional, well-to-do, district with its large houses and villas in which Witold Lipiński placed an aluminium clad igloo and a composition of co-joined barrels. Acts of which we every much approve. Acts which, arguably, can be considered acts of resistance. Can be interpreted as a demand not only for alternative forms of and approaches to domestic housing design, but a demand to let the environment decide in questions of domestic housing and urban planning. To question which is the more appropriate urban housing form, a large quadratic box or a freely flowing vaulted shell? Which is the better urban planing form, the quadratic grid with planned nature subjugated to humans or a Hobbit village in a forest? Thoughts and questions its hard to arrive at in Shape of Dreams, but which you can’t ignore as you wander around eastern Wrocław.

In addition through visiting the sites you notice just how small Witold Lipiński’s houses are, the models in Shape of Dreams being almost 1:1. Which in no way detracts from or denigrates the works, far from it, but does surprise. Even in a city overrun with dwarves. And that not least because Witold Lipiński’s dreams appear so big, endless, unbound. And also because the works of many of his contemporaries were realised much, often much, much, larger. But is their size a simple reflection of the limitations of the plots on which they stand, bigger structures simply wouldn’t have fitted? Or is it reflective of the technical challenges that compound(ed) the mathematical ones: both the igloo and ‘Mir’ are in brick, how big could they theoretically have been built? Or is there another reason, one to which we shall come to in a few minutes.

And you also realise what an appalling state of disrepair and dissolution all three are currently in, you almost get the impression that some people hope that soon they will fall in on themselves, freeing up the plots.

¿Cynics? ¿Us? ¡Yeah!

A state of chronic ill-health also exhibited by, as one can see from the photos by Jakub Certowicz in Shape of Dreams, the Legnica smelter holiday village in Rokitki, and which helps highlight that while much of the more experimental architecture of the 1960s and 1970s was undertaken with solid understandings of aesthetics, statics and the demands of practical use, it was invariably undertaken with materials whose long term care demands weren’t fully understood. Meaning that today extra effort is often required to maintain them. Effort that isn’t always undertaken. And that not least because, arguably, the positions and ideas of a Witold Lipiński, and his many like-minded colleagues, never fully caught on: we don’t all live in organically formed, thin-shelled, vaulted structures. The greater majority of us live in square boxes. The house of the future is always circular. And is always in the future, never in the now. And thus, arguably, works such as those by a Witold Lipiński which reject the perceived, blithely accepted, supremacy of the quadrat tend to be trivialized and discredited as space age, as science-fiction, as fantasy, as Hobbit Houses, as something to be hidden by an advertising hoarding, something that simply never could be in mainstream human society. A fleeting pipe dream rather than a durable reality. And certainly not worth preserving. ¿Why would you?

However, lest we forget, the houses of the ancient past, and a great many of those created by global communities without the assistance of professional architects, are circular: the Yurts/Gers of central Asia, the numerous roundhouses of Africa, the numerous roundhouses of the Celts, the igloo. Whereby Witold Lipiński’s Wrocław igloo, as one learns in Shape of Dreams, is not an igloo, he hated it being called an igloo, ¡Przepraszam!, but was primarily inspired by the roundhouses of ancient Slavic communities. (Although it does resemble an igloo.) The houses of the past were circular, the houses of the future will be circular, we live in quadratic boxes. ¿How did that happen? ¿And must it be so? ¿Are we content in our quadratic boxes? ¿Would we be more content in vaulted shell forms? ¿Are boxes or vaulted shells the most appropriate form for housing in and for contemporary and future realities? ¿Do we want to live with the natural environment or as masters of the natural environment? ¿What shape are our needs and demands?

¿Are our dreams the same shape as a 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński’s?

¿And if they are……..?

A compact, concise and endlessly engaging exhibition Shape of Dreams not only allows one to begin to approach the positions, methodology, relevance and legacy of a 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński, and to appreciate how he sought during that period to transform theoretical mathematical manipulations and geometric juggling into physical forms, but also to better appreciate his motivations, the why he undertook such work; motivations that, as one learns in context of his own house, his own igloo, his own Slavic roundhouse, were not only concerned with statics and resolving the complex problems of the design and implementation of shell structures and vaulted forms, of achieving increased “plastic ingenuity” in architecture, but were also concerned with seeking to improve the energy efficiency of buildings and also improving the internal environment, further important aspects of his long and varied career: Lipiński authoring over the years numerous reports on various microclimate, psychophysical and bioclimatic aspects of buildings and homes, and also being associated, if we’re currently admittedly unsure of the exact relationship, with the Szkoła Architektury Bioklimatycznej, School of Bioclimatic Architecture, an institution established in the mid-1970s within the Wrocław Architecture Faculty and which concerned itself with not just bioclimatic aspects but also ecological aspects of architecture and construction. Aspects which tend to locate the works on show in Shape of Dreams not just in context of the space and science fiction of the 1960s and 1970s but also in context of the awakening environmental and ecological movements of the period. And which may also be the aforementioned possible reason for the modest size of the Wrocław houses, they may be scaled to achieve a maximum of ecological and bioclimatic efficiency. Possibly. Are certainly from brick, recycled bricks in the case of Lipiński’s own Slavic roundhouse, by way of reducing both cost and environmental footprint. And also by way of making it an object anyone could build, without specialist machines or knowledge. A further sustainability factor.

What is also certain is that his considerations on ecology and bioclimate meant that his own house, his own Slavic roundhouse, as one learns in Shape of Dreams, was populated as much as by plants as by humans, and that the design of the house was as much focussed on achieving a positive living space for the plants as for the humans. Arguably about enabling a symbiotic environment, a mutualistic environment, for both plants and humans. An alternative take on uniting the interior and exterior as components of a whole as expressed by the ‘Mushroom’ at the junction of Wyścigowa and Turniejowa. And a further extension of a Witold Lipiński’s understandings of connections between the natural environment and the built environment. And a further ongoing relevance of the work and positions of Witold Lipiński. One of numerous ongoing relevancies that can be gauged and appreciated in Shape of Dreams.

Relevancies that are not unimportant in context of our contemporary, and future, 3D printing and AI; developments which may be able to resolve not only many of those complex analytical problems associated with naturally occurring forms, but also the many technical challenges of realising such, and thus enable the construction of ever more Formy swobodne i dowolne, Free and Arbitrary Forms, enable the much greater “plastic ingenuity” in architecture a Witold Lipiński demanded. And whose reasons for pursuing he can elegantly and convincingly articulate.

No one is arguing that Witold Lipiński is the best and most important architect in the (hi)story of Poland, and how would you frame that argument anyway? However, through the introduction to 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński, through the introduction to the work, approaches, motivations and positions of 1960s/1970s Witold Lipiński, Shape of Dreams not only very neatly and very satisfyingly employs Witold Lipiński as a conduit for reflections on architecture and design, but for all very much allows an otherwise rarely heard but without question informative and instructive voice to contribute to discussions on not only the (hi)story of architecture and the built environment, but also, and most importantly, the future of architecture and the built environment. And, and as with all discourses and discussion on the future, the more voices we have, the better, for, as we all know, the future is an ongoing “problemem złożony”, complex problem…….

Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński is scheduled to run at the Muzeum Architektury, Bernardyńska 5, 50-156 Wrocław until Sunday March 31st.

Full details can be found at http://ma.wroc.pl

Photos by Jakub Certowicz of works by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

Examples of circular rotational forms (front) and model of a prefabricated centrally folded form building (rear) by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

Photos of ‘Mir’ and a proposed commercial pavilion by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

A house by Witold Lipiński with an offset terrace so as not to block the path of the light through the curtain wall, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

A flying saucer house sat in a hollow by Witold Lipiński, as seen at Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

A 12th century archivolt watches over Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński, Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław

1. Witold Lipiński, Powłokowe formy sklepione, Prace Naukowe Instytutu Architektury i Urbanistyki Politechniki Wrocławskiej, Wrocław 1978, as quoted in Shape of Dreams. Polish really, really isn’t our strongest language, therefore we are relying on the translations as presented in the exhibition.

3. Witold Lipiński, Decyduje Pejzaż, Polska, Nr 11 1975 pages 24-25

Tagged with: Muzeum Architektury, Poland, Powłokowe formy sklepione, Shape of Dreams, Witold Lipiński, Wrocław