Into the Deep. Mines of the Future at the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

Of all the novel technological developments of the past century or so, or more specifically those novel developments in context of mobility, arguably, none have approached the human species’ imagination, spoken to the human species’ fantasies nor so tantalisingly promised that limitless future we all innately know is possible, to quite the degree of the airship; arguably a form of transport that today, all those decades after reaching its zenith as a commercial enterprise, still has an appeal, a fascination, beyond that of the rocket, the plane or even the train.

And a development facilitated to a large degree by aluminium, a, then, still relatively novel material.

A still relatively novel material whose advantages were quickly understood and readily exploited; but whose problems and consequences were, in the golden age of the airship, unknown. Unknowable at that period. But which today are very well documented. And tangible.

With the exhibition Into the Deep. Mines of the Future the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen, employ the aluminium of the earliest airships as a conduit for discussions on future society’s raw materials, and for all for a discussion on the sources and extraction of those materials…….

As an exhibition Into the Deep. Mines of the Future starts where aluminium, more or less, starts: bauxite. That raw material, that sedimentary rock, from which the development of novel processes in the late 19th century enabled an economically viable extraction of the inherent aluminium and thereby made a previously very interesting, but very expensive, metal available and realistic for industry. Including for the, then, fledgling, aeronautical industry where it allowed for the production of the stable, robust, but very light, skeletons demanded: Hugo Junkers, for example, employing aluminium for his aircraft while Ferdinand von Zeppelin employed it in his airships. (Ferdinand von) Zeppelin airships which on account of their role in the development of air travel and air transportation have since become the generic eponym for all airships; Zeppelin airships produced in Friedrichshafen from 1912 until the late 1930s, (and again since the mid 1990s); Zeppelin airships that are, unsurprisingly, the primary focus of the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen.

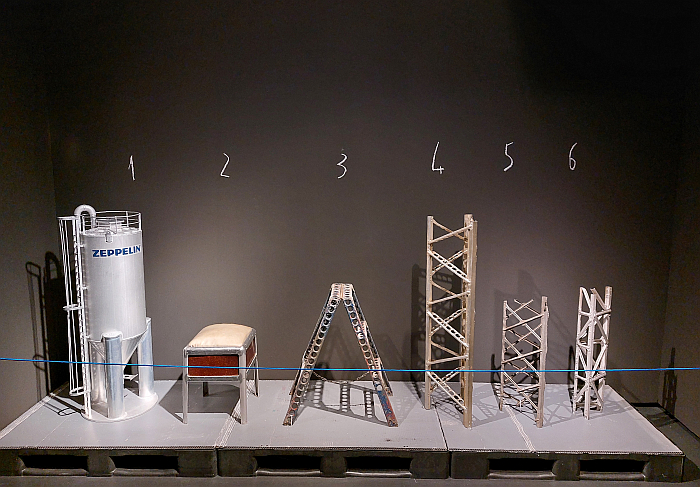

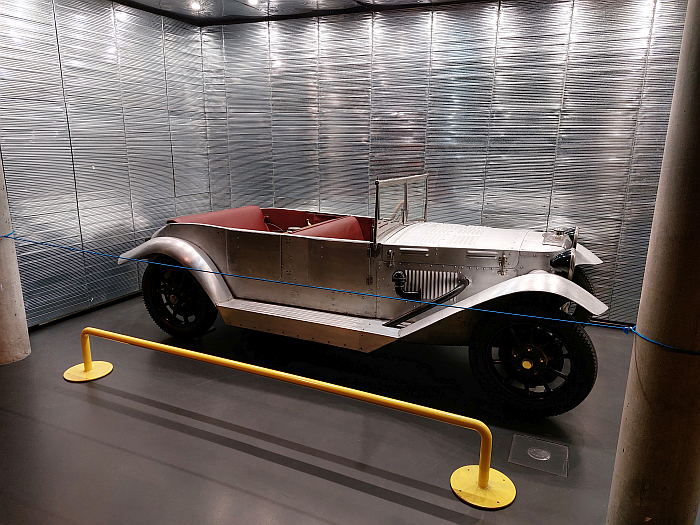

And Zeppelin airships that are also the primary focus of the opening chapter of Into the Deep; an opening chapter illustrated, narrated, by, for example, a reconstruction of the gondola from the LZ 1, that first prototype Zeppelin, a gondola whose supporting trusses were, as the curators note, crafted from pure aluminium, and thereby, as it transpired, lacked the required strength and rigidity, and so were not only cast for later Zeppelin’s in aluminium alloys but also re-designed from their original T-form to a triangular construction; by examples of such triangular trusses from the 1910s to the 1930s which thereby explain how the construction evolved, and which in the lightly quadratic U profile into which the aluminium alloys have been folded to form the three component beams remind very much of the legs of the contemporaneous Rowac-Schemel, and thereby not only helping set the Rowac-Schemel in context of the industrialisation of its age, but deliciously underscoring how such a simple fold can increase the strength of a material and thereby allow a reduction in the use of that material; by a 1930s stool employed by the Zeppelin crew which in its simplicity of form stands diametrically juxtaposed to the chairs that can be enjoyed, at least visually if not physically, in the museum’s permanent exhibition’s recreation of a Zeppelin lounge, a 1930s stool that in its double functionality as a storage solution is a very informative and illustrative example for furniture in restricted spaces and/or spaces that need to perform numerous functions, a 1930s stool that in its aluminium is very much of the age. And also illustrated and narrated by a car. Or more accurately, an experimental car developed in 1925 by the German mining and metallurgy concern Schwäbische Hüttenwerke, which features, alongside a so-called Soden transmission from Zeppelin, an aluminium body developed by Zeppelin.

An opening chapter which while extolling the many advantages of aluminium not only manages to avoid sounding like a Troy McClure narrated infomercial on either aluminium or Zeppelins, but also manages to find space and time to highlight and discuss the negative social and environmental consequences of aluminium consumption, including the damage done acquiring the vast amount of bauxite needed to feed the global aluminium appetite, the energy demand of aluminium production, and also making mention of the bauxite tailings, the toxic red mud that by necessity results from the extraction of aluminium from bauxite.

And a very brief opening chapter; which is no way a complaint, for it is but an introduction to aluminium by way of setting the stage for the main presentation and its focus on the Mines of the Future of the exhibition’s title: deep sea mining and deep space mining.

A replica of the LZ 1 gondola displaying the original trusses, as seen at Into the Deep. Mines of the Future, Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

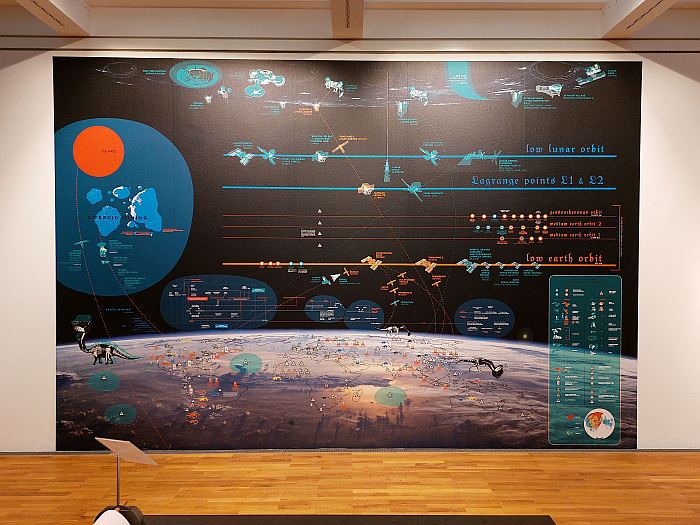

A focus led by five art installations: Two in the chapter Deep Sea Mining. One in the chapter Deep Space Mining. And two not so much spanning both as setting both into context of contemporary realities and the decisions that as a global society we need to make.

The former three covering with the project Prospecting Ocean by Armin Linke, in cooperation with Giulia Bruno and Giuseppe Ielasi, the question of who owns the seabed, and for all, who thereby owns the metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al contained therein?; with Kristina Õllek’s multimedia project Nautilus New Era touching on the myriad ecological questions associated with deep sea mining; while Bethany Rigby’s project Mining the Skies explores similar questions of ownership, motivations, processes and consequences in context of deep space mining.

The latter two represented via Bureau d’études’ Astropolitique map with its charting of both mining and extraction operations past and present on earth, and their social and environmental consequences, and also of the plans being laid by companies and nations to enable space mining. And via the film From Mars to Venus. Activism of the Future by Ignacio Acosta with its juxtaposition of the Swedish arctic with Chile’s Atacama Desert, two regions rich in the iron and copper of old industry, and which have suffered, are suffering, on account of that wealth, and two regions whose rare earths and metals deposits make them interesting, important, locations for the future terrestrial mining necessary for the novel technologies and novel products intended to replace those that required the iron, copper etc, mines that got us into our current malaise. But which in being such could see them contribute to new problems, and/or an exacerbation of the existing, thereby continuing their suffering rather than alleviating it; which is a lovely loop to travel and to consider. And thus two projects which provide a stimulating framework in which to consider not only mining, but the demands of human societies past, present and future, the myriad interdependencies between human societies and the planet, and also the raw materials of which human society is composed.

As does the very nice, very simple, and very, very elegant link Into the Deep forges between the planned mining of space and the seas for the metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al future society needs, and the aluminium, and the mining and processing of bauxite, undertaken by past and present society. Viewing the five installations one continually returns to the early 20th century and the rise, pun intended, of the Zeppelin. Thanks to its aluminium skeleton.

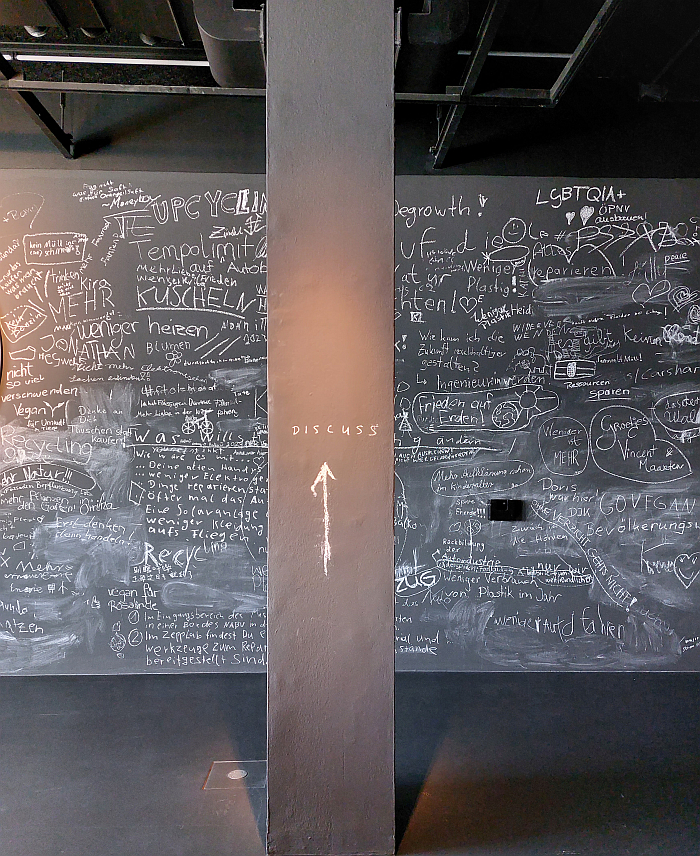

All of which not only helps Into the Deep elucidate contemporary realities and the decisions to be made, but which in doing so is very much an invitation to contribute to a very urgent, and very complex, discussion.

From Mars to Venus. Activism of the Future by Ignacio Acosta, as seen at Into the Deep. Mines of the Future, Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

Whereby the first question you’re encouraged to pose, a question Into the Deep poses on various occasions and in varied contexts, and which it poses very audibly, unmistakably so, is whose metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al, are they? Who should decide what happens to them?

That question that went unposed in centuries past in context of not only aluminium but of all those metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al extractable by terrestrial mines, where it was blithely accepted the answer was: the owner of the ground on which the mine stood.

But did they? Really? Why? And what if they hadn’t, what if they’d been a universal common good? Or was it the nature of their ownership that allowed them to contribute to the progression of human society? Was it the nature of their ownership that allowed them to contribute to our contemporary social and environmental challenges?

Similarly the question, if we need the metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al to be found under the sea and in space? Who decided we do?

That question that went unposed in centuries past in context of not only aluminium but of all those metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al extractable by terrestrial mines, where it was blithely accepted the answer was: Yes!!!

But did we? Really? Why? And what if we’d explored alternatives? How does one define progress? How does one define innovation? Who defines innovation and progress?

Questions which cause one to question if as a species humans are capable of learning lessons from the past? Can Homo faber process the experiences of the past in context of contemporary realities? Can Homo faber extrapolate that which the past has taught us into a future we all know we will influence through our decisions but will, in all probability, not live to experience? Can Homo faber appreciate deep sea mining and deep space mining in context of our experiences with coal mining, iron ore mining, uranium mining, bauxite mining, et al? Or is Homo faber blinded by its hunger?

Questions of ownership, necessity, progress, innovation, benefits, consequences, Homo faber, etc that all lead into what, in many regards, is the key question Into the Deep poses: Do we want deep sea mining and deep space mining?

A question that forces you to add the missing question mark to the exhibition title: Into the Deep. Mines of the Future?

A question time is running out to answer.

Or perhaps more accurately, time is running out to pose.

Aluminium tresses and furniture from Zeppelins, and aluminium Zeppelin silo, as seen at Into the Deep. Mines of the Future, Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

For deep sea mining is very much on the cusp of becoming an actual thing. July 2023 being an important month in that process marking as it does the moment when the vast majority of the global seabed, which until now has been deemed the “common heritage of mankind”1, a universally owned domain, and where mining was strictly controlled, is now, effectively, free game and that for no other reason than the inability of global governments to go beyond their self-interest and agree on things.2 And while deep space mining may be further away than deep sea mining, may still be a vision rather than a thing, as Into the Deep elucidates preparations and planning are well advanced. And seriously intended.

Why?

The oversimplified answer is emerging technology, novel energy concepts and mobile digital technology.3 Rare earths and metals such as, for example, tellurium, niobium, cobalt or zirconium that are important in much of our novel technology exist in much higher concentrations on the seabeds (and in space4) than in the earth’s crust, thereby allowing for a more economic extraction, and ensuring the future of, for example, our photovoltaic solar cells, our batteries, our superconductors, our computer chips, our self-cleaning ovens, our wind turbines, our energy efficient light bulbs, etc, etc, etc. And our flying cars. Obviously.

Which very neatly focusses attention on the fact that it all comes down to us, collectively and individually.

Very neatly focusses attention on the fact that its all being done in our name. In the name of the progress of the human species. Innovation. And that, deliciously, and discombobulatingly, very often in context of technologies intended to move us on from those systems, fuels, processes and objects which have so contributed to our current problems, but which may, ¿will?, cause their own new problems and/or exacerbate the existing. A situation succinctly, and most poetically, reflected on in Ignacio Acosta’s film with its juxtaposing of the past, present and future in the Swedish arctic and Chile’s Atacama Desert. And a state of affairs that was joyously highlighted on the day we viewed Into the Deep via the number of lycra clad pensioners visiting the Zeppelin Museum on their pedelecs: excellent things for not only cutting greenhouse gas emissions but also for enabling individuals to maintain an independent mobility beyond an age that was possible in times past, a factor which can but have a positive impact on the social fabric of any community, and the mental health of a great many individuals; but objects that are very dependent on the metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al under the seabed. And in space. And thus very dependent on the (¿inevitable?) negative consequences of their extraction. The phenomenal ugliness of contemporary pedelecs and the fact that the greater majority present themselves with a naked hostility, a wanton aggression, shouting at all and sundry with an arrogant, ignorant, menacing, misanthropic tone that bodes ill, beautifully encapsulating the mix of the practical and the problematic that is the contemporary pedelec. And which, yes, also makes the contemporary pedelec a metaphor for rare earths and metals.

What are we to do?

???

Prospecting Ocean by Armin Linke, in cooperation with Giulia Bruno and Giuseppe Ielasi, as seen at Into the Deep. Mines of the Future, Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

On the one hand, we’d argue, and having viewed Into the Deep, it’s partly a design challenge, something in many regards neatly explained by the redesign of the trusses on the LZ 1, an example of the fact that, and to invoke and paraphrase a Le Corbusier, a simple decision can sweep away obstacles and thereby clear less a path for life as a path for new options.5 How things are designed defines not only how they work, and the relationships possible, but their resource needs. Thus changing a design changes the impact. Are there, for example, alternative ways to enable the advantages of pedelecs without the rare earths (and the aggression)? A question which also retains and maintains the above noted metaphor. Such is also a technical challenge, clearly, one in which designers and engineers will need to work together, but does interdisciplinary research not produce the most meaningful results? And is the job of designers, the function of design, not to reimagine that which exists in better, more meaningful, more pleasing, less problematic, more democratic ways? And not to design things that exacerbate existing problems and/or create new ones, that primary focus a Victor Papanek accuses (industrial) designers of inherently possessing.

And on the other, we’d argue, and as Into the Deep very much admonishes, it involves us all finally accepting the challenges and realities of raw material depletion: Much like climate change was something that was long seen coming but which it was assumed we’d somehow find a way to side-step and so no-one really prepared for it; and much as AI was long seen coming but which it was assumed would never fully arrive and so no-one really prepared for it. So limitations of the supply of raw materials.

Which brings one back to aluminium, a material that wasn’t just seen as the future in the 19th/early 20th century when the likes of Junkers and Zeppelin employed its properties in their flying machines, but thanks to its intrinsics properties, not least is lightness, corrosion resistance, ready formability, fire-resistance and high-gloss shine it remained the future throughout the 20th century, not least in America where its advantages were quickly understood and throughout the 20th century it was increasingly employed in not only the aeronautical industry but for kitchen equipment, packaging, construction, cars, or furniture, that in 1960 the Eames launched an aluminium collection was no isolated act on their part but, as, for example, Clive Edwards explains, was a moment on a path that has started decades earlier6, a path that also included the aforementioned Zeppelin aluminium storage/stool. And aluminium that was particularly associated with the streamlining of the 1930s, a moment undoubtedly, unquestionably, inspired and informed by the Zeppelin, and where any consumer good, be that a fridge or a radio or a sideboard or a food mixer or a whatever, could be improved by the ornamental, decorative, addition of aluminium. Or ruined, depending on your position.

Thus, as the 1952 US Government study Resources for Freedom noted, “aluminum has come, within a span of 65 years, from nowhere to place alongside the staples copper, lead, and zinc. By 1953 it can be expected to lead all metals but steel”, and for all its use had “grown ninefold in the last 25 years”, a growth curve that was going to continue, if somewhat slower, the report gleefully predicting, “future demand for aluminum may quite possibly quintuple over the period 1950 to 1975, both in the United States and in the rest of the free world”. However, as they noted, “there should be no fundamental difficulty in meeting the free world demand over the foreseeable future, however rapidly it may grow”.7 And the more distant future? That unforeseeable but very much existent future? The report’s authors are very much describing a developing dependency that won’t be easy to break.

A 1925 experimental Schwäbische Hüttenwerke car featuring an aluminium body, as seen at Into the Deep. Mines of the Future, Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

While, and perhaps more informative in terms of “meeting the free world demand”, the report notes that “the United States currently obtains about one-third of its bauxite requirements from domestic deposits”, i.e. can’t meet its ever increasing demand from its own resources, adding that, if demand increased as predicted, “the presently known ore reserves of the Western hemisphere would be about two-thirds consumed by 1975”.8 And then? Did no-one think, hang on, wait a minute, stop: we’re increasing our use of a non-replaceable resource, of which we already have too little, towards a dependency that we may not be able to satisfy, is that not a problem……..?

???

OK, we didn’t run out of bauxite, if the USA is now, effectively, entirely dependent on imports, and as such one could use the example of aluminium as an argument not to listen to worry weasels who predict the worse. 🙋

Alternatively, OK, we didn’t run out of bauxite, if the USA is now, effectively, entirely dependent on imports; but, on the one hand the position of the 1952 report is representative of a, we’ll argue, prevailing attitude at that time, one that can be gauged and assessed not only in reports such as the very programmatically titled Resources for Freedom, but also in the many characters and stories one meets in Vance Packard’s ever informative 1960 book The Waste Makers, and a prevailing attitude that was not only essentially very egoistic, one that placed its own needs above the needs and opinions of all others, and in doing such has more than a whiff of colonialism about it, but one which actively blocked out all possible future problems, for all the future problems of others, in its partisan focus on the immediate (economic) benefits for itself. Which isn’t a healthy attitude. And one that is very contemporary. And on the other, it goes without saying the 1952 report makes no mention of the environmental consequences of bauxite mining and aluminium production, it was 1952 why would it; but does discuss at length the very, very messy process of extraction from bauxite and the high energy demand required, while the implied increasing global transportation of bauxite and alumina that would invariably arise clearly also leaves a not inconsiderable footprint. If a footprint invisible in 1952. And bauxite remains the finite resource it always was, regardless of the (economic) benefits it brings.

But what if rather than using ever more aluminium throughout the 20th century the USA had responded to the very obvious future challenges that had been identified and that everyone could see coming?

What if we’d considered alternatives?

Astropolitique by Bureau d’études, as seen at Into the Deep. Mines of the Future, Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

As an exhibition Into the Deep tends to highlight three principle ways to respond to raw material shortages: using less, for all using less of those metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al that aren’t readily available, that are the hardest to come by, and which means either producing differently, see above re design challenge and lightly quadratic U profiles, or consuming less, certainly consuming better, consuming for decades not for seasons. And on the other via more and better recycling, something mentioned en passant in the 1952 report, whereby, and again very informatively, one of the reasons we didn’t run out of bauxite is increased aluminium recycling in recent decades, something that wasn’t considered a priority by previous generations, because they believed we could and would just keep on mining ever new sources.

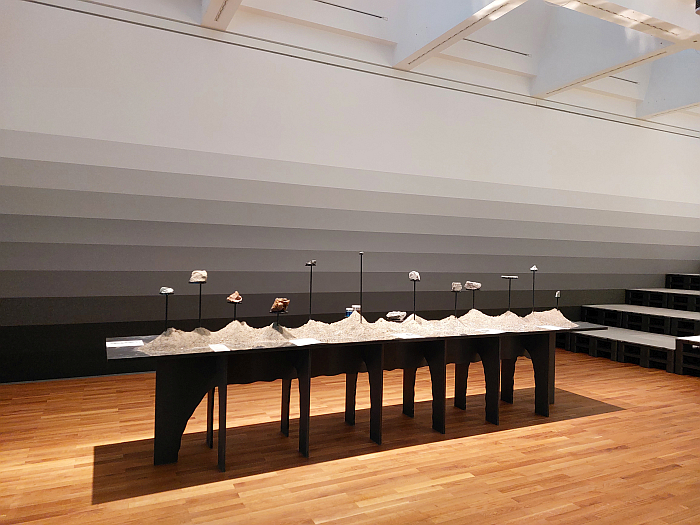

Recycling approached by Into the Deep in various contexts including examples of early 20th century recycled Zeppelin aluminium in the form of commemorative medals from crashed Zeppelins, which while not that meaningful as objects are informative in terms of the development of the Zeppelin mythology, but also through its making note of, for example, the manner in which the English recycled the aluminium from those Zeppelin’s that were shot down in the First World War; via the exhibition design which in its efforts to be climate neutral is constructed from a mixture of elements recycled from previous exhibitions, and objects whose function has been temporarily misappropriated for the duration of Into the Deep, including pallets that are seating but will again be pallets and shelves that are wall cladding but will again be shelves. And, and most directly in context of the theme at hand, via the so-called Sustainability Lab, a space which helps explain on the one hand the widespread use of rare earths and metals in everyday objects such as, for example, laptops, solar panels, artificial joints or robotic vacuum cleaners — ¿remind us, where’s the problem with vacuuming? — and which then through the very simple methodology of asking visitors to collect those objects that you posses allows for an indication of your personal dependence on such rare earths and metals before, through returning them to where they were, i.e. recycling, helps illustrate how recycling makes the resources available for others. Very simple, but very effective.

And also reminding us all that while recycling and using less can be effective we can also reduce our raw material dependency through questioning if just because something is possible, it must be?

That question that global society has studiously refused to approach over its centuries of progress and innovation. Of course it must be, being the universal cry. Why not ?!?!? And whereas in times past we may have gotten away with dodging the question — we didn’t run out of bauxite and in all probability won’t — we are going to have to face it eventually, for all if we insist on building our futures on metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al at the depths of the seas and space.

And which, as so oft in Into the Deep, brings one back to the Zeppelin.

Mining the Skies by Bethany Rigby, as seen at Into the Deep. Mines of the Future, Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen

Airships may have approached the human species’ imagination, spoken to the human species’ fantasies and so tantalisingly promised that limitless future we all innately know is possible, to an unmatched degree, and may remain alluring and enigmatic, you simply cannot help but stand transfixed as they float over Friedrichshafen, and comparing the Zeppelins with the stream of private jets flying into Friedrichshafen airport is an easily recommendable activity when in Friedrichshafen. As is querying why Lufthansa need four flights a day from Frankfurt to Friedrichshafen? Four!!! But were airships ever anything more than an embodiment of the human species imagination, fantasy, desire for freedom, were they ever of relevance beyond the emotional and the figurative? Why didn’t they help Germany win the First World War? Would air travel and transportation have developed quite happily without them? Were they interesting in terms of theory but less so in practice? Did they distract from other challenges in terms of mobility and transportation in the early 20th century? Did our confusing of a figurative functionality for a practical functionality put us on the wrong path?

Similarly today, how much of the technology enabled by the metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al to be found in elevated concentrations on the seabeds, and in space, is actually needed, is actually meaningful and practical, and how much is responding to an egoistic desire, or to a playful fantasy or to a collective, culturally conditioned, unquestioned, preconception about what represents progress and innovation and the future? How much of it is potentially distracting us from other challenges, and thereby, potentially, setting us off on the wrong path? How much of that which was realised with aluminium in the 20th century was important, and how much wasteful? How much did we need, how much could we have happily gone without?

Do we need autonomous food delivery robots if that means mining the ocean floor? Do we need self-cleaning ovens if that means mining the ocean floor? Do we need autonomous robotic lawnmowers and vacuum cleaners if that means mining the ocean floor? Do you need multiple smartphones if that means mining the ocean floor? Do we need flying cars…..?

Honestly, do we need flying cars? Did we need the Zeppelin?

Who needed the Zeppelin? Who needs flying cars?

Who decided we needed the Zeppelin? Who decided we need flying cars?

Do we need to base future society on metals, minerals, ores, rare earths et al that are increasingly difficult to source and whose extraction for all that it will without question bring us the novel, may also bring us unknown problems, invariably will bring new social and environmental problems, social and environmental problems we currently cannot imagine, much as the exploitation of aluminium did.

Questions and considerations enabled by Into the Deep which very neatly focusses attention on the fact that it all comes down to us, collectively and individually.

There is a convincing argument to be made that aluminium and plastic are very much the materials of the 20th century, those materials that enabled the advances, the progress, the innovation of the 20th century as well as being those materials of the problems of the 20th century, much as cast iron and steel were the materials of the advances, the progress, the innovation of the 19th century, and the materials of the problems of the 19th century. Rare earths and metals are inarguably the materials of the 21st century…….it’s up to us. It’s (almost) here. There’s no side-stepping it. No dodging. We’ve got to face it.

Through its very simple, and very satisfying, conceit of establishing a dialogue between aluminium and rare earths and metals, a dialogue between the past and the future, and that in a presentation based primarily on art installations rather than scientific inquiry, Into the Deep allows one to approach the myriad issues, advantages, problems and challenges inherent in our contemporary and future raw material supply and use from alternative perspectives than those normally available, and in doing so helps underscore that human society must move forward, must develop and evolve, must progress, must remain innovative, will always need raw materials, but that a balance always has to be struck between those musts and the inevitable negative consequences that will arise. A balance that until now hasn’t always been achieved, and that, so the suggestion, on account of the discussions being largely defined by dominant, vested, interests, and thereby the need to find a new basis and form for such discussions. For more transparency and honesty and open-ended dialogue, less dogmatically fighting one’s corner.

But for all Into the Deep helps elucidate the complexity of the decisions that need to be made about our future raw material extraction and use, underscores that convincing arguments can be made on both sides, but ultimately a decision will have to be made: Do we want deep sea mining and deep space mining?

A question only the minority of us have ever posed, and which, despite the importance of the question for the future of human society and our plant, one that the vast majority of us have no position on.

Into the Deep is a good place to start forming your position.

Yes, it would have been better if we’d all considered it earlier, but better late than never…….

Into the Deep. Mines of the Future is scheduled to run at the Zeppelin Museum, Seestraße 22, 88045 Friedrichshafen until Sunday November 5th.

Full details can be found at www.zeppelin-museum.de

1. UN General Assembly Resolution 2749 (XXV), Declaration of Principles Governing the Sea-Bed and the Ocean Floor, and the Subsoil Thereof, beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction, 17th December 1970

2. Although deep sea mining has been technically possible in territorial waters, much as oil and gas drilling is, it was not only strictly controlled in international waters under Part XI of the so-called United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a convention in force since 1994, but all profits from such extraction were to be shared amongst all peoples. Which clearly didn’t appeal to commercial operations. A framework from the distribution of that income didn’t however exist. And, and without going into too much detail, the agreement contained a clause which, if triggered, effectively gave the responsible International Seabed Authority two years to devise that framework or else the mining company could keep all the profits. Which is and was very much in their interests. In July 2021 Nauru triggered that clause, and it goes without saying that as an international body with hundreds of members, the International Seabed Authority hasn’t developed a framework in the necessary two years. Thus the “common heritage of mankind” in the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the North Pacific is now, in effect, the property of Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. And clearly other companies will manage to pull of the same trick for other regions.

3. There’s also advanced medical applications involving rare earths and metals, which clearly should be considered separately from consumer goods. And arguably also given priority in the distribution of existing supplies where they have a significant medical benefit

4. Arguably deep space mining is not as well researched as deep sea mining, for fairly obvious reasons; however main focus is currently asteroids which are rich in the so-called Platinum Group Metals, PMGs, and also the moon which has a variety of materials, including Helium-3 which has numerous scientific and medical uses, and could, possibly, be important for the nuclear fusion reactors we’re working towards and which promise us all that glorious future of unlimited energy. There’s also loads of aluminium on the moon. And cheese, obviously…….

5. see Le Corbusier, The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics, Harvard University Press, 1954, page 15 for the original quote and context

6. see Clive Edwards, Aluminium Furniture, 1886-1986: The Changing Applications and Reception of a Modern Material, Journal of Design History, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2001, 207-225

7. Resources for Freedom: A Report to the President, A Report to the President by The President’s Materials Policy Commission, June 1952, Volume II – The Outlook for Key Commodities page 65ff

Tagged with: aluminium, Armin Linke, Bethany Rigby, Bureau d'études, Deep Sea Mining, Deep Space Mining, Friedrichshafen, Ignacio Acosta, Into the deep, Kristina Õllek, Mines of the Future, Zeppelin, Zeppelin Museum