As Bob Dylan once wrote, but The Byrds most elegantly enunciated, "I was so much older then, I'm younger than that now".

Same with us...

...aaach, what the heck...

...after neigh on 17 years, and over 2,100 posts, 2.4 average a week, for all you stats nerds, I can drop the character for one post, and step through the fourth wall to join yous in the auditorium.

Hi! How are you? Good to meet you!

17 years ago I... ohhh!!, that feels weird, if exhilarating... 17 years ago I was much older. I could illustrate that fact. But it's probably better that I don't. Those who were there know the posts. Know the older me. Apologies to you all, that was then.

17 years later, I'm younger than that.

And am delighted that I am.

Near all antonyms of 'ageing' are very negative, make it sound like a bad thing, but regression in maturity is surely something to be celebrated.

Verner Panton once opined, "in the kindergarten one learns to love and use colours. Later on, at school and in life one learns something called taste. For most people this means limiting their use of colours."1 A tragedy for a Panton. He yearned that we could all regress from our conditioned use of colour with its rules and structures and experts to that joyous, savage passion for colour we'd once lived as an intrinsic part of who we are. Imagine the world if we all did. Where's the negative in that?

Charles Eames once opined, "not having lived long enough, children are naturally uninhibited and see everything as new and interesting; they are observing and associating all the time"2, in contrast to adults who know, or these days have someone on Instagram or TikTok telling them. Or have ChatGPT telling them. And so don't observe, associate, take interest. A tragedy for a Charles and a Ray Eames. They yearned that we could all regress from our conditioned seeing to the freedom with which we once saw, to that joyous, savage passion for the world we'd once lived as an intrinsic part of who we are. Imagine the world if we all did. Where's the negative in that?

And, yes, I would accept there is a strong suspicion of dreams of romantic facts of musketeers in discussing childhood from an age before the smartphone replaced imagination and curiosity as the defining, constant companion of children, but I passionately hope it's only a suspicion.

And even if I'm wrong on that, the argument remains the same, regression in maturity is surely something to be celebrated.

A regression in my context thanks to two things. One of which is design.

A design that back in the day existed in my skull as lies of black and white, was very easy to describe; but which over the years has become an infinite, swirling confusion of grey hues.

A decolourisation, a dissociation, and the associated regression through empowering savage passions, that while everything has contributed to it, be that the conversations with protagonists of all ilks, the hours in libraries and archives, the study of the Historia Supellexalis, the study of the Radio smow playlists, the design weeks, the design school presentations, even the trade fairs, a key function has been performed by the 100s of architecture and design exhibitions I've visited.

For it is in architecture and design exhibitions that one learns not only to engage with design openly, honestly, posing questions, listening attentively to answers, arguing back, but it is in exhibitions that one learns to transpose, extrapolate, that which is being presented and discussed in new contexts and realities, to leave the space you are in, and thereby to learn to appreciate design for what it is. Not as that thing for sale in the shop window.

That's not design. That's a monetisation of design. A necessary and important monetisation: in any society based on money rather than happiness, where 'growth' is of wealth not character, design, as with all cultural practices, needs a monetisation to enable designers to continue their art. Or as Run DMC enquire of us all: "Won't you tell me the last time that love bought you clothes?"

When?

Exactly!

"It's like that and that's the way it is". "Huh".

Those who produce design, those who help advance design in theory and practice, must be fairly paid for what they do; those who profit from design, from design positions, from design theories, who profit from those who help advance design in theory and practice, should, must fairly pay those who enable those profits through their creativity. Not all do, a great many get away without doing it. And when they do not only the individual creative suffers but the progression of design suffers. Which is why they needs must pay.

In context of design culture and commerce need each other, but one should never confuse the one for the other. And certainly shouldn't confuse the impetuses and motivations of one for the impetuses and motivations of the other. They are intrinsically pulling you and society in very different directions. The tension inherent is however of fundamental importance. Must be maintained.

And, yes, and I would agree, there is, again, a strong suspicion of a dreaming of romantic facts of musketeers in not only such an opinion but in that which I've been doing these past 17 years; however, not only am I no d’Artagnan, Don Quixote is the more apposite comparison, although I do very much adhere to the premise of 'One For All And All For One', regardless of the undeniable fact it has become of late another wedding vow, but maintaining such a suspicion is to ignore an important difference between me and Mr Dylan. One of several important differences.

And a centrality of architecture and design exhibitions in my regression that is why I keep insisting you visit more.

And while, again, there is, yes, a suspicion of something of me telling you what to do about my monthly lists of recommended exhibitions, such is to ignore an important similarity between me and Mr Dylan, one of several important similarities: the fact that part of my, our, regression is a cessation of telling you what to.

Bob and I used to do it all the time. Both stopped a long time ago. OK, the odd cry of "We’ll meet on edges, soon" or "Equality" may ring out from these dispatches from time to time, but that's just bad formulation on my part, invariably written quickly in a moment of high agitation and not properly edited later. I know we should be discussing where and when we want to meet, if we want to meet; and what is 'equal' in such a complex world of juxtaposed desires, needs, passions? We should be discussing the relationships between equality, impartiality, justice, coexistence, respect, dependency, independency, fairness, openness, emancipation, society, transparency, et al not getting hung up on one or the other term at the expense of all others.

For my part I stopped telling yous what to do not on account of any fear that I’d become my enemy, In the instant that I preach, although I am now very much aware of the similarities between the older me and them, and appalled by what I was; rather I stopped telling yous what to do because design taught me not to preach. Design doesn't preach. Design would never preach. Design invites to discourse. Design never tells you what to do, or what to think, or how to speak. Design doesn't 'know'. Design has no interest in right and wrong. Design has no interest in defining the terms 'good' and 'bad'. Design leaves you to work it all out for yourself. Design challenges you to work it out for yourself. Design is a tool. One common among all species, not exclusive to humans.

A lesson taught by design which is also why whereas back in the day abstract threats, Too noble to neglect, Deceived me into thinking, I had something to protect, these days I appreciate that in the arrogance of my previous maturity, in my all knowing former old age, I wasn't protecting design, certainly wasn't doing design any favours. As I've regressed I've increasingly come to appreciate that I can let design fend for itself. And should let design fend for itself. Must let design fend for itself. Design doesn't need anyone to fight its corner for it. Least of all me.

Design has been under attack for decades, and always will be. But design don't care.

It'll keep on doin' its thing. 'cause it's all it can do.

And I'll keep on doin' my thing. 'cause it's all I can do.

And I'll keep on learnin'.

And I'll keep on visitin' architecture and design exhibitions.

And I'll keep on rippin' down hate ice cream wherever I come across it. A truly pointless flavour. Waste of everyone’s energy. Why give it space in the deep-freeze of life?

My... still feels weird, but also weirdly fun... my five recommendations for new architecture and design exhibitions opening in September 2025 can be found in Vienna, Tallinn, Melbourne, New York and London......

(And with which I'll quietly take myself off back behind the velvet curtain...)

Amongst the myriad problems of the blithely told, and unquestioningly re-told, narrative of the development of creativity in the late 19th/early 20th century, and thereby of the incompleteness of the inter-dependent narrative of the development of society in the late 19th/early 20th century, is the absence of that which was part of the period but isn't part of the contemporary popular narrative.

Normally because it's not as sexy, nor as readily marketable, as that which is part of the contemporary popular narrative.

One of the more important popular omissions being, inarguably, the influence of esotericism and the occult on the developments of the period.

An influence of, a fascination with, esotericism and the occult that, in many regards, can be considered as arising in the more radical fringes of the various Reform movements of the late 19th century, those proto-hippys who were so influential in the development of Art Nouveau, and their search for responses to the, for them, obvious dangers inherent in the rapidly advancing mechanisation of the period. Nature and folkloric offered not only refuge from the machine, an alternative reality and future, but numerous interpretations on what the non-human world is, was and its relationships to the human being. Interpretations that regularly became mixed with, confused with, visions of perceived national identities.

An influence of, a fascination with, the occult, and wider esotericism, at the turn of the 19th/20th century Vienna's Leopold Museum aim to explore in the company of a roster of protagonists as varied as, and including many others, Gabriel von Max, Edvard Munch, Oskar Kokoschka, Erwin Lang or the Egon Schiele who is such a primary focus of the Leopold Museum. And whereas we've not seen the name 'Rudolf Steiner' in any information on Hidden Modernism, we wouldn't be in the least surprised to find him lurking in a corner somewhere.

The latter three, four should Steiner appear, as Austro-Hungarians, standing representative of a Fascination with the Occult around 1900 in Vienna that promises to be an important focus of Hidden Modernism; a Viennese fascination with the Hidden of the occult that, as with the Hidden of the psychoanalysis of Sigmund Freud or the Hidden of the atonal music of an Arnold Schönberg, found its way via various vectors to Bauhaus Weimar. A link that further helps underscore the international character of that institution, the international influences on that institution. And an occult/esoteric impulse from Vienna, in addition to the impulse from Switzerland via the conduit of Johannes Itten of the occult/esoteric Mazdaznan — there was a goodly mix of occult/esoteric at Bauhaus Weimar — that means, amongst its many other claims to fame, Bauhaus Weimar had one of the first vegetarian student cafeteria menus in Europe. A thought always worth reflecting on.

Thus a presentation that aside from allowing for more nuanced approaches to the role of the occult, and esotericism, in the developments of the decades around 1900, including elucidating that looking back on those decades from today the Hidden of the title is to be understood in terms of In Plain Sight, should also offer an alternative perspective on late 19th/early 20th century Vienna, on the composition, motivations, influences of that very important early 20th century Viennese avant-garde, across all creative, scientific and civic genres, than is normally popularly accessible.

And in doing such should also allow for a comparison of the origins, influences and development of a fascination with the occult and the esoteric in early 20th century Europe, and where that took European society, with the origins, influences and development of a fascination with the occult and the esoteric in our early 21st century Europe of rapidly increasing autonomous technology and desires to ever more closely and rigidly define national identities.

Hidden Modernism. The Fascination with the Occult around 1900 is scheduled to open at the Leopold Museum, MuseumsQuartier, Museumsplatz 1, 1070 Vienna, on Thursday September 4th and run until Sunday January 18th.

Further details can be found at www.leopoldmuseum.org

In our age of instantaneousness, an age when time, in many regards, has been replaced by action, where time is something that was, something that hindered society past, our age when Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times appear more Modern than ever, if in novel contexts, slowness, deliberate slowness, is radical. Slowness is resistance. Arguably the most intransigent, hardline, fundamental form of protest.

¿And possibly an answer to our contemporary malaises?

¿Or a symptom of an irrational fear of progress?

With The Politics of Slowness Tallinn's Adamson-Eric Museum aim to explore and discuss resistance to the instantaneousness, timelessness, speed, of contemporary society via the conduits of art, craft and design by way of stimulating a discourse on not only the tempo of contemporary society but on alternatives, on the question if alternatives are viable, if alternatives are possible.

¿Still possible, but not for much longer?

¿Still possible, but a mistake?

A presentation to be structured around three central themes — time as a real and abstract phenomenon, the effects of the pace of contemporary society on the individual human being, 'slow' technologies and materials — approached in the company of an international, primarily Baltic, roster of creatives working in and across a variety of genre and media, including, for example, Sandra Kosorotova, Sten Saarits, Nele Kurvits or Krista Vindberga.

Thus an exhibition that aside from its primary focus, a focus it appears well prepared to do justice to, should also neatly continue, and expand upon, the considerations on questions of time posed in and by presentations such as, and amongst others, Time, Freedom and Control – The Legacy of Johannes Bürk at the Uhrenindustriemuseum Villingen-Schwenningen, or Uneversum: Rhythms and Spaces at the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, Tallinn, in new contexts and dominions. A component of that important regular re-framing of familiar questions of society we needs must undertake. But only rarely do.

And an exhibition whose location should, in addition, allow for reflections on time, slowness, in the canon of Adamson-Eric, in context of both his artistic works and his applied arts. Thereby enabling access to not only differentiated perspectives on Adamson-Eric and his influence in and on the development of applied arts, craft and design in 20th century Estonia, but to more nuanced reflections on the (hi)story of design as a practice in Estonia as a component of the global (hi)story of design.

The Politics of Slowness is scheduled to open at the Adamson-Eric Museum, Lühike jalg 3, 10130 Tallinn on Friday September 19th and run until Sunday January 4th.

Further details can be found at https://adamson-eric.ekm.ee

Inaugurated in 2022 as a platform for increasing the visibility of contemporary female creatives, one those appalling sounding concepts that is sadly necessary in a 21st century design industry, and 21st century design museum industry, clinging to a patriarchy it believes it needs for its existence, because men told it it did, while providing no evidence, the annual MECCA X NGV Women in Design Commission sees a... woman in design...,... commissioned... to develop a project for... Melbourne's NGV International... museum where it is subsequently presented in a curated exhibition space.

Following on from Tatiana Bilbao in 2022, Bethan Laura Wood in 2023 and Christien Meindertsma in 2024, the 2025 MECCA X NGV alumnus is Nipa Doshi.

A graduate of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, India, that design school, and digressing slightly, established in 1961, largely on the basis of Charles and Ray Eames' 1958 India Report and as realised by an international collective based around former staff and students at the HfG Ulm, including Hans Gugelot, thus a thoroughly fascinating and instructive moment in design (hi)story, one briefly discussed in these dispatches in context of the 2013 exhibition Designing India at the, contemporary, Centre for Innovation and Design at Grand-Hornu, Hornu, an exhibition co-curated by Nipa Doshi that we regrettably never saw but that from afar stimulated us and sent us off in all manner of joyous directions... a graduate of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, India, Doshi subsequently completed a Masters at the Royal College of Art, London, where she met Jonathan Levien with whom she formed the studio Doshi Levien. And from where the pair have developed an array of projects for international manufacturers and brands as varied as, for example, Hay, Kvadrat, Moroso or Richard Lampert, in addition to cooperations with Paris based Galerie Kreo. And producing/curating the aforementioned Designing India.

Freed from her role and responsibilities in Doshi Levien, and from the compulsion of commercial success, the latter that, for former Vitra CEO, longtime Vitra guiding light, Rolf Fehlbaum "unmerciful censor of all ideas"3 — if you doubt RF just look around you — Nipa Doshi has developed for NGV International the project A Room of My Own: a cabinet inspired and informed by the ancient Indian, specifically Rajasthani, art of Kavad, essentially a wooden storage box whose decoration tells stories.

Yet whereas the traditional Kavad re-tells epics of Gods and Heroes and Folklore, Nipa Doshi's Kavad promises to tell a more personal tale, one of those females, of those cultural influences, of those intersections, that have contributed to her development as a person and as a designer, and also to her appreciations of the world, of the realities of global human society. While being, one presumes, we haven't seen it, a practical sideboard.

Thus a project that should not only allow one to better approach Nipa Doshi, designer and person, but also enable fresh perspectives on the development of design as a global practice. While reminding us all that when viewing works of design the superficial object shouldn't ever be our focus. It is but the packaging for transporting that which is important.

MECCA X NGV Women in Design Commission 2025: Nipa Doshi is scheduled to open at NGV International, 180 St Kilda Road, 3006 Melbourne on Thursday September 25th and run until Wednesday April 1st.

Further details can be found at www.ngv.vic.gov.au

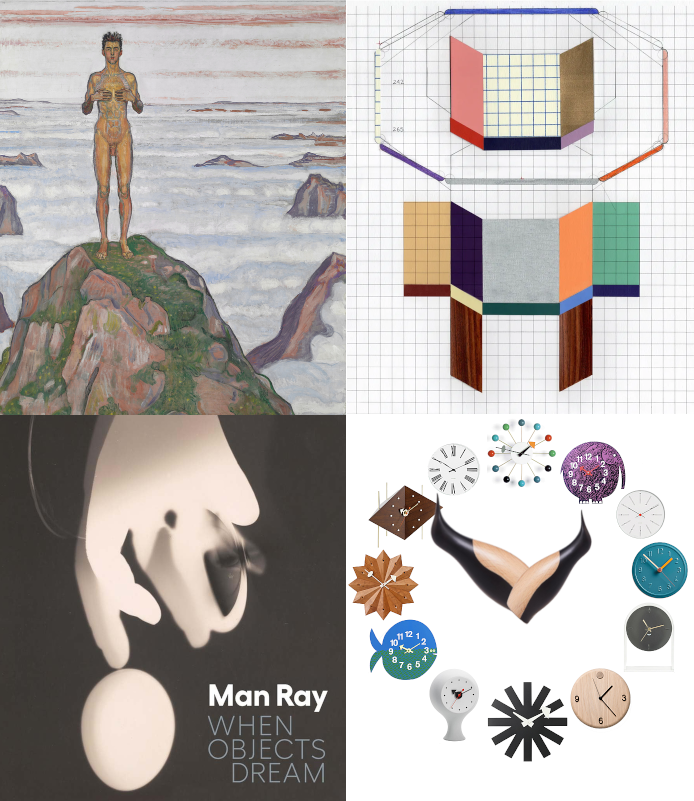

Born as the much plainer Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia in 1890, Man Ray counts amongst the more experimental creatives of the early decades of the 20th century. An individual who crossed generic borders as easily and as often as he crossed international borders, and thus was an important influence on the development of creativity of all hues on both sides of the Atlantic.

Amongst Man Ray's many contributions to the (hi)story of 20th century creativity is and was the so-called rayograph, essentially nothing more remarkable than Man Ray's take on the long-established photogram, that art of photography without a camera; but which through the manner in which Man Ray approached his compositions made them important moments in the development of not only Dadaism and Surrealism but also of the myriad avant-garde moves away from the Expressionism of the earliest years of the 20th century.

Rayographs The Met, New York, aim to explore in When Objects Dream, an exhibition The Met claim, a claim we see no reason to contradict, is the first exhibition to attempt to locate the rayographs in context of Man Ray's wider 1910s and 1920s canon. An exploration that in addition to presenting some 60 rayographs, which is a rarely seen concentration of dreaming objects in one location, also promises contemporaneous objects, paintings, prints, films and more conventional photographs by Man Ray. A creative counter-balance that will include, amongst other works, the tack-studded-iron Gift, the metronome Object to be Destroyed, or his 1929 work Swedish Landscape, which it may or may not be, it's hard to tell, but it is a further development of the rayograph. A Swedish Landscape as a reminder that creativity isn't static. Which, yes, you're right, is a sentence we didn't need, but very much wanted.

Thus a presentation which should not only help to better locate the rayographs in Man Ray's formative years, as a moment in Man Ray's development, but which in its scope and inherent conversations should also allow one to better approach an important, interesting and instructive creative.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream is scheduled to open at The Met, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York, on Sunday September 14th and run until Sunday February 1st.

Further details can be found at www.metmuseum.org

Whereas 1960s and 70s Düsseldorf had its Creamcheese, a basement club where the city's creative avant-garde, not least those associated with the near-by Kunstakademie, would met, dance, debauch and advance their art of all hues, 1979-1981 London had its Blitz: a basement club, a basement den of meeting, dancing, debauchery and creativity, in the near vicinity of St Martin’s School of Art and the Central School of Art and Design which, despite its fleeting existence, its blitz of an existence... sorry!!!... was not only highly, arguably disproportionately so, relevant for the developments in creativity in the Thatcherite UK of the 1980s, prepared the ground for an important flank of the popular resistance to the Thatcherite UK, but remains relevant to this day. Shaped more than the 80s of the title.

Launched in 1979 by Steve Strange and Rusty Egan, who along with Midge Ure formed the band Visage who remind us that, ultimately, we all Fade to Grey, there's no point in fighting it, Blitz was a space in which the ethos of punk was freed from the dogma it was becoming and allowed to take on new expressions, to explore alternative aspects of its being, was allowed to metamorphose. That thing punk isn’t allowed to do today.

A space that for all it is popularly best known for giving the world the New Romantics — the unofficial house band were Spandau Ballet and among the so-called Blitz Kids regulars one found the likes of, for example, Boy George, Siobhan Fahey or Marilyn — Blitz was frequented by a hurly-burly of then anonymous individuals who would become influential voices in a variety of creative contexts, including, for example, Perry Haines who co-founded i-D magazine, costume designer Michele Clapton, artist Grayson Perry or Stephen Jones who would become milliner to a Princess Diana who, although living in London as an 18/19/20 year old non-princess in 1979-81, moved in very different social circles to the Blitz Kids. If, reading (hi)story, one gets the impression she would have very much enjoyed herself in Blitz. Very much.

And also musicians beyond the New Romantics, including, for example, Chris Sullivan of Blue Rondo à la Turk or Martin Degville later of the, to this day, outrageously overblown, Sigue Sigue Sputnik.

Before in September 1981 Blitz closed its doors for ever.

With The club that shaped the 80s London's Design Museum seek to explore what Blitz was, why it was, how it was, who it was, what it is, via a presentation that in addition to artefacts of the Blitz club including, for example, clothing, costumes, worn by Blitz Kids, or Spandau Ballet's Yamaha synthesiser as used in Blitz and on their first recordings, also promises to include photographs and archive documents alongside works produced by Blitz Kids in context of their careers by way of exploring the various paths taken since Blitz. And also examples of contemporaneous architecture and design from that London, a setting of the wider scene in which Blitz existed, that world outwith the Blitz basement, including furniture by Jasper Morrison, Tom Dixon or Ron Arad, the latter who in the late 70s/early 80s was ferociously hammering metal in his London workshop with, as previously opined, the aim of making "the immaterial physical". Which may or may not echo that which Steve Strange, Rusty Egan and their Blitz Kids were attempting.

Thus a presentation that in addition to documenting an important moment in the (hi)story of creativity in England, elucidating the ongoing relevance of that, in many regards, highly exclusive moment, and the importance of doing-it-yourself, being-yourself, of grasping the moment regardless of what others are doing — you're not them!! — should also allow one to better question, scrutinise, deconstruct the generality of the term 'Postmodern' as it is so lazily applied to creativity of the 1970s and 80s.

And should also allow one to reflect on, as also discussed by and from Everything at Once: Postmodernity, 1967–1992 at the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, the popularly underrated importance of hedonism in helping society advance.

And of the importance of the nightclub as a vector for that hedonism. Be that nightclub Pacha or Hacienda or Studio 54 or somewhere, somewhere in a field in Hampshire, or Creamcheese or Blitz...

Blitz: The club that shaped the 80s is scheduled to open at the Design Museum, 224 – 238 Kensington High Street, London W8 6AG on Saturday September 20th and run until Sunday March 29th.

Further details can be found at https://designmuseum.org

Rather than a static photo, we thought, why not a little music to allow one to better transpose oneself to that London of old? Specifically To Cut a Long Story Short the first single, the breakthrough single, by the Blitz unofficial house band Spandau Ballet:

[If you're not seeing a video here, there's an embedding problem... but do find and watch the video, it's well worth it]

1Verner Panton, Lidt om Farver/Notes on Colour, Danish Design Centre, Copenhagen, 1997, page 24

2Charles Eames, Lecture at University of California, Berkeley, 23.09.1953 (transcript), re-printed in Daniel Ostroff [Ed.], An Eames Anthology, Yale University Press, 2015, page 121

3Rolf Fehlbaum, Ein Projekt mit ungewissem Ausgang in Alexander von Vegesack [Ed.], Citizen Office. Ideen und Notizen zu einer nueun Bürowelt, Steidl, 1994, page 8