Designing India

As part of the bi-annual Europalia Arts Festival the Belgian cultural institute Grand Hornu is currently presenting the exhibition “Living Objects – Made for India”

Curated by London based design studio Doshi Levien “Living Objects” is, as the title cleverly implies, an exploration of everyday Indian objects, everyday Indian design as it were, and an exhibition that in the words of Nipa Doshi and Jonathan Levien should be seen as “…a vehicle to discuss Indian culture, Indian values and Indian way of life.”1

Which all sounds like good, clean, wholesome fun.

What we however find much more interesting is Doshi Levien’s wider intention, namely that all the presented objects “…will be uniquely Indian but reject narrow nationalism.”

Because such a discourse has been one of the central themes of Indian design ever since….. well since ever, and is one of the aspects of design in India that make it such a fascinating subject.

British colonial rule being the insensitive beast that it was, all aspects of Indian social and cultural life during the period of London’s domination of the region were narrowly tied to furthering the imperial ideals. Including of course education and the popular representation of arts and crafts.

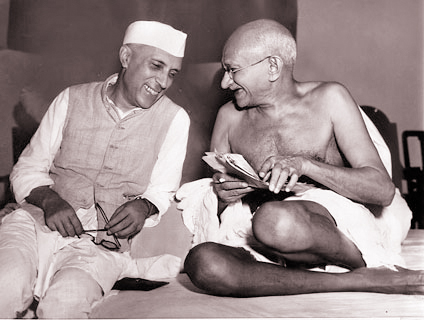

According to Saloni Mathur one consequence of this policy was that until India gained independence from Britain in 1947, design in India was “promoted as the traditional arts and crafts of the village and distinguished against industrial production.”2 Something which would have no doubt intently annoyed Wilhelm Wagenfeld. Yet which equally unquestionably pleased Mahatma Gandhi and which he, in effect, used against the British “occupiers” in form of his Khādī movement which sought to empower Indians through creating a self-sufficiency in consumer goods. Self design and self production for self rule, as it were.

Post Independence – and one must add post Mahatma Gandhi – Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru began a modernisation programme which broke with the systems of yore, broke with Gandhi’s teachings and which strove to associate Indian nationhood with increasing industrialisation or as Mathur, somewhat disparagingly, refers to it “Nehru’s hubris was to believe that India could catch up in its delayed modernity by accelerating the pace of industrialization—by building new dams, offices, iron and steel plants, factories, airlines, and cities at a historically unprecedented rate.”3

In addition to large scale architecture and urban planning projects by the likes of Le Corbusier or Louis Kahn, design led production was a central pillar of Nehru’s vision/hubris.

The problem was of course that India had no history of design led production. And Indians had no experience of design led consumption.

And so it proved fortunate for Nehru that on account of its strategic geopolitical significance, post-Colonial India was an important ideological front in the Cold War. A front in which America invested very heavily.

In a design context, an important facet of America’s “India Campaign” was played by the New York Museum of Modern Art.

In 1955 the MoMa organised the exhibition “The Textile and Ornamental Arts of India”. Essentially a celebration of traditional Indian handicraft “The Textile and Ornamental Arts of India” presented around 1000 items in an exhibition designed by Alexander Girard and was, according to Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., the then director of the MoMa Industrial Design Department, largely concerned with improving US-India relations.4 Culture as politics.

More significantly, in 1958 the MoMa organised, at the behest of the Indian Government in the persona of the National Small Industries Corporation (NSIC), the exhibition “Design Today in America and Europe”. Presenting some 300 examples of “well designed household furnishings and equipment”5 in an exhibition design created by George Nelson Associates, “Design Today” opened in New Delhi in January 1959 and spent the next two years touring India, attracting over 1 million visitors as it went.6 Although clearly comparable with the “Design for Use, USA” exhibition that spent two years touring Europe, in contrast to its European cousin “Design Today in America and Europe” was, at least publicly, much more philanthropic and was, according to the MoMa press release intended as a “…. guide to the rapidly increasing small industries developing in response to the changes in India’s social and economic life”.7

Changes in India’s social and economic life which also played an important role in one of the most celebrated and discussed American contributions to the development of post-war Indian design, The India Report by Charles and Ray Eames.

Living Objects - Made for India. A selection of water carriers (Photo: © Serge Anton - Europalia India 2013)

At the invitation of the Indian Government and with the financial support of the Ford Foundation Charles and Ray Eames spent three months in 1957 touring India, investigating and studying the design culture. Much as Charlotte Perriand had done in Japan at the request of the Japanese government two decades previously.

As many commentators have noted, whereas the Indian Government expected a report that would indicate how design could benefit the Indian economy, what they got was much more an analysis of the current social condition in India and a report that indicated how design could help Indian society. “In the face of the inevitable destruction of many cultural values – in the face of the immediate need for the nation to feed and shelter itself ” Charles and Ray Eames noted, ” a drive for quality takes on a real meaning. It is not a self-conscious effort to develop an aesthetic – it is a relentless search for quality that must be maintained if this new Republic is to survive.”8

Or put another way, India expected product design, and got, largely, social design.

A central feature of the Eames’ India Report was the necessity of the formation of a national design institute to educate and train students and to “prepare them to meet problems in design, problems which have occurred many times, and problems which have never occurred before – and to meet them all openly and inquiringly.”9

An argument and solution that of course also assisted Nehru in his attempt to “…liberate design from its traditional association with colonial art education”10

On the basis of Charles and Ray Eames recommendations the Swiss photographer Ernst Scheidegger and Danish architect Vilhelm Wohlert were commissioned to develop a plan for such an institution and the resulting National Institute of Design (NID) opened its doors in September 1961. Largely modelled on Bauhaus not only was the teaching and programmatic concept of the NID predominantly shaped by the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm but it counted amongst its first teaching staff Ulm alumni including HK Vyas, Sudhakar Nadkarni, Herbert Lindinger, Christian Staub and Hans Gugelot.11

Despite its auspicious birth, brave new world outlook and official support for the institution and its goals, the initial impact of the NID was, at best, limited. Or as Osamu Note states, “from its establishment in 1961 up to the 1980s the NID remained an anonymous institution in terms of public awareness”, arguing that “the high percentage of independent designers among the graduates of the 1980s suggests a lack of social recognition for the utility of their expertise”12

An argument poetically reciprocated by Nipa Doshi who attended the NID from 1989 until 1994 and in context of her decision to study design writes, “”Design” unless it was “fashion” or “interior decoration” was still unheard of as a serious career path to follow in India.”13

That the NID was so ineffectual in its early years was, with hindsight, to be expected.

In the first decades after independence India followed a protected, planned economy that focussed much more on local production than quality, imports were restricted and choice was strictly limited. Consequently, as Ashoke Chatterjee writes, the first wave of NID graduates entered a world where “the business community regarded design as a postponable luxury, or as an option to be applied after a product was developed rather than integrated into the development process”14

It should therefore have surprised no-one that the response of most Indian designers of the period was, why bother?

However by the time Nipa Doshi graduated the social and cultural changes in India that followed the political changes of the late 1980s and early 1990s had altered that landscape and according to Note “the period opened up new opportunities for NID graduates, whose expertise, and the benefits associated with that expertise, had long been under-used”,15 and which for Ashoke Chatterjee meant that, “designers who had been urging industry for years to acknowledge the centrality of their role now were being challenged to deliver design of a quality and at a speed entirely new to their experience”16

Had design finally established itself in the Indian psyche? Had Indian consumers learned to embrace design led consumption?

No.

Or at least not entirely.

For despite these transformations and modern India’s position as one of the leading players in the global IT sector, design and India remain uncomfortable bed fellows; and India a country where the traditional culture of invention, creating new from old and of making do with what one has, remains a strong as ever. Or as Doshi Levien state, “Most everyday objects found in Indian homes are not designed by professionally trained ‘designers’. There is a real culture of improvisation and customisation to suit individual needs.”17

A situation which can in many ways be seen as an inevitable consequence of the conflicting positions that have accompanied the development of design in India.

From Gandhian nationalism versus Nehruvian nationalism, over Design as social innovator versus Design as economic innovator and on to consumerism versus protectionism, one can see in India a clear desire for design, but no clear, unifying, concept as to what design should be and how it should be integrated into contemporary Indian society.

Or in the words of Charles and Ray Eames, “What does India ultimately desire? What do Indians desire for themselves and for India ?”18

We’ve not seen “Living Objects – Made for India” and so can’t say how the objects selected by Doshi Levien answer such questions.

Should we, we will let you know.

And should you wish to discover for yourselves, “Living Objects – Made for India” runs at Grand Hornu, Rue Sainte-Louise 82, 7301 Boussu, Belgium until Sunday February 16th 2014.

1. Doshi Levien (2013) “Living Objects – Made for India” Press Release. http://caracascom.com/files/7480_GHI-Living_Objects-UK.pdf Accessed 06.11.2013

2. Mathur, Saloni (2011) Charles and Ray Eames in India. Art Journal, Vol. 70, Issue 1. The College Art Association New York, NY

3. ibid

4. ibid

5. Design Today in America and Europe” Press Release 16.01.1959 http://www.moma.org/pdfs/docs/press_archives/2439/releases/MOMA_1959_0005.pdf Accessed 06.11.2013

6. Karim, Farhan Sirajul (2013) “MoMA, the Ulm and the development of design pedagogy in India” in Jhaveri, Shanay (Ed.) Western Artists and India. Creative Inspirations in Art and Design. Thames & Hudson, London.

7. “Design Today in America and Europe” Press Release 16.01.1959 http://www.moma.org/pdfs/docs/press_archives/2439/releases/MOMA_1959_0005.pdf Accessed 06.11.2013

8. Eames, Charles and Ray (1958) The India Report

9. ibid

10. Mathur (2011)

11. Karim (2013)

12. Note, Osamu (2006) Designing after the modern: The making of designers and their imagining of the future in postcolonial Southern India, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 29:2, 255-277,

13. http://www.doshilevien.com/media/item/29/596/DL-Biography-2012.pdf Accessed 06.11.2013

14. Chatterjee, Ashoke (2005) Design in India: The Experience of Transition Design Issues 21. no. 4

15. Note (2006)

16. Chatterjee (2005)

17. Doshi Levien (2013)

18. Eames (1958)

Tagged with: Charles and Ray Eames, Doshi Levien, Grand Hornu Images, Living Objects - Made for India