Wilhelm Wagenfeld Reviews Design for Use, USA

As many of you will be more than aware, it is very rare that a genuine expert reviews an exhibition for these pages; however, in the case of the 1951 exhibition “Design for Use, USA” we have one.

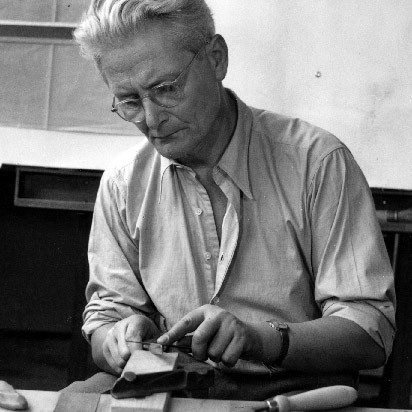

The German silversmith, product designer and Bauhaus alumni Wilhelm Wagenfeld.

At least indirectly.

On January 5th 1951 “Twenty-five thousand pounds of American home furnishings exhibition material”1 departed the Museum of Modern Art in New York to begin a two year tour of Europe. Curated by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., Director of the MoMa’s Industrial Design Department, “Design for Use, USA” showcased a broad selection of contemporary American domestic design including electrical goods, crockery, cutlery, textiles, toys and of course furniture.

The exhibition premièred in March 1951 at the Stuttgart Landesgewerbemuseum before moving on through Italy, France, Switzerland and the UK.

In our previous post on “Design for Use, USA” we leaned quite a long way out of our bejewelled turret window to assert that the exhibition could be seen as the moment Europe first became properly introduced to post-war American design, and so initiated a sensitising process that ultimately led to the popularity of not only Eames, Nelson, Saarinen et al, but also of the Egon Eiermanns and Arne Jacobsens of our world.

Reading Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s review of “Design for Use, USA ” in the May 1951 edition of the magazine Baukunst und Werkform2, we feel more than a little justified in our youthful arrogance.

For all through the fact that Wagenfeld confirms that while many of the objects were known to Europeans through magazines and photos, “Design for Use, USA ” offered a first opportunity to “…take the objects in our hands and sense how one sits in the chairs and at the tables, how the luminescence of the table and floor lamp radiates. We can see if the wooden handle of the tea pot allows us to both correctly hold it and to pour tea, and how that tea subsequently tastes in the cups”

From Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s review one gleans that the exhibition not only made a very positive impression on him, but that much more it underlined for him the spirit of the age, specifically, for Wagenfeld “Design for Use, USA” showed an unmistakable and unstoppable move away from handicraft and towards industrial production. “Wir leben so zwischen den Zeiten” he asserts, “We’re living between epochs”

Not that this unmistakable and unstoppable move was something that Wagenfeld approved of per se. Despite his close association with industrial production Wilhelm Wagenfeld was a tireless advocate of the artistic soul of a product, industrial production shouldn’t become a means to an end in itself and for Wagenfeld mass production for profit alone was a contemptible misuse of technology and resources. Indeed in a 1934 lecture to the Brandenburg-Pommern Regional Group of the Deutscher Werkbund Wilhelm Wagenfeld harangued, “In the current age machines and handicraft are intimately interwoven with one another. Industry often presents an alternative image: Machines and handicrafts locked in a bitter battle until the crafts are destroyed. That is how it often appears. But that is just a smokescreen of the industry, of those who want to make us slaves: us, and our machines and our handicrafts.”3

And so it comes as no surprise that he uses the platform offered by Baukunst und Werkform to bemoan the quality of much industrial production, “…whenever one reads an industry magazine, regardless from which country it originates, one is presented with the repugnant, with the same mediocrity, in the same vast quantities and with the same might. As if some international conglomeration of the sedulous, small minded industry and economy have decided to once and for all abolish human dignity”

Gotta’ love that man!

For Wilhelm Wagenfeld the brave new world towards which “Design for Use, USA” was taking us was one defined by the materials from which it was constructed.

The synthetics and plastics he found “very pleasing” and for him they bore no resemblance to the, inferior, German materials of the day. For all the synthetic textiles impressed Wagenfeld as “…structurally and chromatically wonderfully suited to their purpose. One had the impression that the presented synthetic textiles were unlikely to deform under influence of temperature or moisture”

But also the wood, aluminium, steel et al impressed Wagenfeld, and one can sense his genuine respect for the way his US colleagues had shown the bravery to experiment and to push such materials to the very limit of what, in those years, was technically possible.

Consequences no doubt of the fact that while in the immediate post-war years Europe was largely concentrating on rebuilding, America was free to invest in scientific and technological research. And hence our argument that despite the obvious overtones of back-door colonialism such exhibitions invariably carry with them, it made perfect sense to show “Design for Use, USA” in the early 1950s. America was simply further developed than Europe, and so we could learn from what was presented.

Although Wilhelm Wagenfeld, somewhat naturally, devotes the greater part of his text to the more traditional, craft based, objects and lighting, he does also cover in some detail the exhibited furniture.

Among the objects that particularly caught his attention were Ray Komai’s moulded plywood side chair – an object that the exhibition catalogue feels obliged to explain is created from one piece of wood, presumably because they assumed nobody would otherwise believe that it was – and two chairs by Eero Saarinen, objects which judging from the photos in the catalogue were to become the Womb Chair and the Executive Chair.

And although the “well known through many published images plywood chair” wasn’t presented, Wilhelm Wagenfeld gives a very positive report of the Charles Eames‘ furniture that was included, even if “…the aluminium shelving and pedestal with colourful plastic panels appears a little complicated”.

He means the Eames Storage Unit, ESU. And “complicated” isn’t the first, or indeed fortieth, word that occurs to us in the context of that particular object.

But then we really are in no position to disagree with a Wilhelm Wagenfeld…..

Eames Storage Unit, ESU by Charles Eames (here in a modern Vitra version). Wilhelm Wagenfeld found it “…complicated…”

It is a widely acknowledged truth that designers don’t write. Most claim they can’t. Most of them can. But either lack the confidence to put pen to paper or simply duck the challenge with half-hearted claims of overwork.

The consequence is that design criticism and design theory is largely dominated by individuals who not only have never designed anything but who potentially lack the basic creative talent to correctly apply jam to toast.

And that is a shame, because as Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s text ably demonstrates, the designers perspective on new developments and the state of the design industry are much more valuable, more relevant and frankly more interesting, than the mercenary ramblings one normally reads.

And so we give the last word here to Wilhelm Wagenfeld, who ends his review of “Design for Use, USA” with words of caution for his contemporaries; “Without doubt the exhibition presents the best the USA has to offer, but we should not lose sight of the fact that today poor quality goods can be produced everywhere, uniform, abundant and with ease. No country can build an export industry on the basis of such objects, for such, the best that we can produce in our age, is only just good enough”

1. “MUSEUM’S “DESIGN FOR USE, U.S.A.” EXHIBITION SAILED FOR EUROPE” http://www.moma.org/docs/press_archives/1483/releases/MOMA_1951_0001_1951-01-04_510104-1.pdf Accessed 27.07.2013

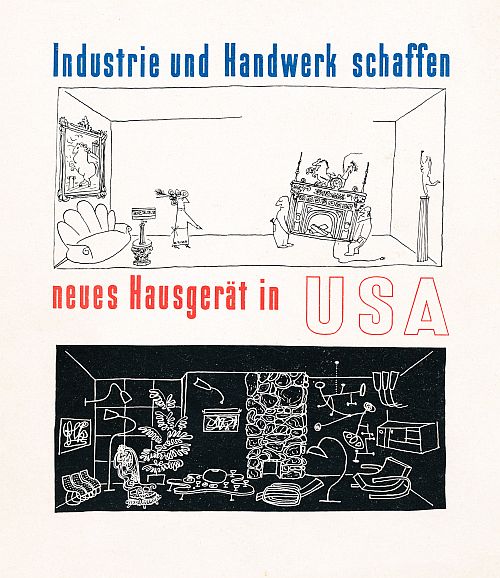

2. (And all quotes unless otherwise referenced) Wilhelm Wagenfeld “Neues Hausgerät in USA” Baukunst und Werkform, May 1951 43-46

3.Wilhelm Wagenfeld “Qualität und Wirtschaft” in Die Form: Zeitschrift für gestaltende Arbeit 1934, 1, 1-4

Tagged with: Design for Use USA, Stuttgart, Wilhelm Wagenfeld