For reasons too well understood to need mention here, the last couple of summers largely passed by without design school end of year exhibitions, or at least not in the manner and with the public accessibility we all once enjoyed and cherished. And as an inevitable consequence, our Campustour came to a grinding halt.

Summer 2022 sees the return of the universal end of term exhibition. But not of the Campustour.

Not that we've lost our passion for randomly traversing Europe, consuming improbable amounts of falafel and complaining, far from it, they remain three of our four favourite pastimes. Much more the frameworks and structures that enabled the Campustour need to be refired, need to be awoken from their pandemic enforced idleness; and that, as with the refiring, the re-awaking, of any blast furnace, takes time. Thus for 2022 we will, regrettably, only post from those student showcases we're fortunate enough to meet in the course of our wider travels, starting in one of the more historically interesting locations in context of European architecture and design, Weimar, and the Bauhaus University's Summaery 2022.......

The unrestricted return of Summaery is not only very welcome in itself, but also a most welcome opportunity for us to, once again, observe that the weather in Weimar was much more Autumnaery than Summaery when we arrived on the banks of the Ilm. A joke older readers will remember was a legal obligation in Campustour posts from Weimar; and which was anything but funny this year as we froze to our core walking from the train station to the Uni. Was proper baltic.

And a return to Weimar that allowed us to move on from the "unparalleled disaster that was our visit to Summaery 2019", an evening that will remain with us for some time, but which we do also need to start putting behind us.

Summaery 2022 helped.

Not just on account of the convivial atmosphere around the campus when we were there, nor only on account of the wide range of projects and positions on display across all departments, nor nor only only on account of the absence of ZDF@Bauhaus's all-dominating, arrogant, stage with its hoard of security, but primarily on account of the number of works on show in the design department we argued with. Argued with in a positive sense; for all the exhilaration of stumbling across a project or a work that delights every nerve in your being, those that irritate you to distraction are just as valuable. For if we all accept, and you don't have to, but it would be helpful if you pretended you did for the next few minutes, if we all accept that design is a position, then that position needs to be continually approached from various perspectives in order to remain meaningful, to stop it become stale and tepid, and for all needs to continually question itself, needs to continually question why it is delighted, question why it is irritated, needs continual discourse, needs continual argument, needs to be continually challenged.

Summaery 2022 did all that.

As ever with posts from end of year exhibitions, important isn't what was realised but how the individual student got there, what they learned along the way, how that journey informed their approach to design, how that journey informed their understandings of design and the role, function, of a designer, among a great many other personal factors that while invariably components of the realised work, remain for the wider public unseen, unseeable. The works themselves are of secondary importance. If still important and interesting. And also as ever, what follows isn't a "Best of Summaery 2022", that's not the way we rock, it's simply what caught our attention, what got us thinking, what moved us, what we couldn't keep to ourselves. It's not definitive. Nor exhaustive. We invariably miss things.

Summaery in Weimar was, as ever brief, lasted but a weekend, and has now passed; however, a re-cap of Summaery 2022, and of previous editions, can be found at www.uni-weimar.de/summaery

As ever at Summaery our first port of call on arriving at the Bauhaus University was the presentation of desks and workstations by second year product design students. A project that has been a firmly established component of the course of studies at Weimar for many a year, one untold numbers of Weimar students have progressed through, and a project, a component of the course of studies at Weimar, that we really enjoy, not least because it always allows for new perspectives, differentiated insights, on the desk, an object, a furniture genre, which contemporary designers largely completely neglect: ever since the large wooden roll top desk ceded to the modern efficiency desk in the first decades of the 20th century desks have essentially remained the same, and contemporary desks notably lack the deep scrutiny, the questioning investigation, the passionate re-imagining, the effort, that is naturally, self-evidently, afforded the chairs and the lamps with which they are so closely associated. And which desks also deserve; particularly so now as we move into an era of ever more home and hybrid working and of a requirement for desks that aren't desks but are desks.

This year's project was staged under the title Study Need? = Work Need?, as part of wider considerations on the social and work cultures in the product design department, and amongst many interesting proposals we were particularly taken by Versatile Table by Imani Fee Hallein and Lisa Sauer, a pleasingly unassuming yet confident object that enables the transition from sitting to standing work in a satisfyingly analogue, tech-free manner. If a solution, we'd argue, highly impractical in context of daily use, has a clunkiness in its operation that can but bring problems with it; however, with a bit of re-imaging, and/or the development of a larger furniture system of which it is but a component, could be a very interesting solution not only in advancing more ergonomic work, nor only in allowing home-office desks that aren't desks yet are desks, but also in reducing the energy footprint of office-offices without having to do without height adjustable desks, just side-stepping the (unnecessary) electronic mechanisms.

Although ostensibly about future-proof objects for transporting people and goods in urban landscapes, Lightweight Transport Scenarios was much more about allowing students an opportunity to develop and refine their 3D computer-aided design competence. And to develop and refine their competencies in optimising bionic topologies; not that we're certain we fully understand what a bionic topology is, nor how one optimises it. Albeit a deficiency of understanding which obviously places us in a minority because no-one involved with presenting the results of the course saw fit to explain such an obvious, established, quotidian term. Although it would have been nice if they had, even if just to humour thickos like us.

Not that the strong focus on the technical design process, and whatever a bionic topology may be, meant Lightweight Transport Scenarios didn't also produce a few interesting proposals for future-proof objects for transporting people and goods in urban landscapes.

For our part we were particularly taken with the electronic cargo scooter Mantis by Elisa Bessega, Sylvia Chen and Esther Betz which not only strikes us as being the more elegant cargo bike, objects we admittedly have huge, huge, problems with, but also looks very much like the Post Office bike of the future, being as it must/could be a lot more convenient when you have to make regular stops.

And were also very taken with EFA - Elektrorollstuhl für alle by Filippo Magini which places the cargo bay behind an electric wheelchair. And which we liked because (a) it is a really simple, obvious, re-imagining of the wheelchair, yet of the type that is anything but simple to reach, and (b) because it places the wheelchair at the centre of the solution rather than devising a solution into which a wheelchair can fit, which can accommodate a wheelchair, which can be adapted for a wheelchair. Doesn't make excuses for the wheelchair, rather accepts it as a normal part of everyday life. Which is a nice switch of focus. And which in doing so also asks why can't wheelchair users work in not only urban transportation and distribution, but generally in the local level movement of goods and people? A question you've never asked before, because it's not possible. Except it is. And if that impossibility isn't impossible, could there be others? What could we all see if we all collectivity shifted our focus.......?

We're happy to, and freely accept, that Marginal Gains was a student semester project, and thus primarily, as noted above, about how the resultant objects were developed and how the resultant objects were approached and what the individual students got individually from that process, and not about developing commercial objects to be in the shops tomorrow. And also appreciate that the brief was, in many regards, more about promoting a questioning of our interactions with our myriad anonymous helpers of everyday life in actual use, an important part of a designer's duty to the rest of us and an important component of enabling the development of novel solutions to every problems, rather than being about developing an actual concept, an actual product proposal; however, Marginal Gains was also and, for us, primarily, a delicious illustration of Victor Papanek’s warning that "there are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a very few of them".

For while a couple of the projects did make good arguments for being meaningful, the vast majority represented a rouges gallery of the evils of industrial and product design. No names, no pack drill, it's about the principle not the specifics, nor do we want to give the impression of singling out individual students when the malefaction was collective; but not only did the vast majority of the projects lead to a thoroughly unjustifiable wasteful use of materials and resources, but answered questions that genuinely didn't need posing, that in many regards can't be posed because there is no basis for them. Fixed problems that simply don't exist, except in the overly excitable imagination of a designer who believes their purpose is to improve everything. And in doing so makes everything worse. And where the question was valid, and some were, the straightforward path to a meaningful answer was ardently avoided in preference for a solution that skipped sprightly past the problem to develop new problems and thereby make everything worse, we're thinking in particular of...... no, no names, no pack drill.

Or put another way, far from Marginal Gains most of the projects represented Vast Retrogressions.

And while, yes, as noted above, and freely, gladly, lovingly, accepted, the project was a student exercise in questioning, surely it's not too much to ask that the responses won't lead to the destruction of Earth by 2050. Thoughts which, yes, do lead into the question if the main problem wasn't the brief as set.....

While there can be but few reasonable objections to any project seeking to develop a resource light electric motorbike crafted from a single sheet of aluminium, other than primarily if an alternative material wouldn't be preferable, the project Uni_Zebra did generate, unleash, a veritable flood of objections with us not because of what it is, but what it claims to be. Purports to be.

Apparently, it's a redesign of Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph's Simson Mokick motorbike. But it isn't. Nor can it be. Because it doesn't understand Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph's Simson Mokick motorbike. In everything it does it contradicts the basics, the principles, the ideals, not only from which the Simson Mokick arose, but by which Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph worked. Contradicts how, certainly how a Karl Clauss Dietel, understood the role and function of a designer and the relationships between objects of daily use and us all, individually and collectively. And most shockingly, and unforgivably, of all it closes Dietel and Rudolph's offene Prinzip, Open Principle. ??????????? As a resource light electric motorbike it's all well and good. As a redesign of the Simson Mokick it's an insult. An outrage.

Not that the Simson Mokick isn't in need of a redesign, it very much is, and Dietel was long the opinion that it should be continually further developed as society, technology, materials et al developed. But that must, must, be in context of what and why it is, as in what it inherently is and why it is what it is. Otherwise you don't have a development of the Simson Mokick, but a new motorbike concept. Which is fine. But different. Unrelated.

In terms of that necessary redesign, an electric motor is, as oft opined in these dispatches, unquestionably an excellent idea, not least because it would allow the Mokick to achieve the final of Dietel's Five Big Ls of Good Design, to meet the L it currently isn't, to be Leise, Quiet, rather than being an object you can hear coming two days in advance. But it must be an electric motor that can be integrated into an existing Mokick, for example, in place of the current two-stroke motor, a new motor in keeping with the modular, accessible, transparent, open, concept. In keeping with the concept of object composed of replaceable components which "do not conceal the supporting framework, rather are part of it and relate to the human being". How does Uni_Zebra with its rigid, quadratic, closed, box relate to the human being? What does Uni_Zebra suggest about the nature of the human being and of human society? While the Simson Mokick stood in resolute contradiction to the political system of the DDR, Uni_Zebra embodies that system. Where the Simson Mokick is based on the visual understandings of a Joan Miró or a Hans Arp, on fluid, organic associations between forms in space, Uni_Zebra forms space in a rigid, unresponsive, uncommunicative, manner.

In addition, we'd argue, and do repeatedly argue, the Simson Mokick is also in need of an update through components that can be 3D printed: open source, printed on demand components for an open, resource light, readily reparable motorbike. The range of materials with which we can currently 3D print, and those with which in the future we'll be able to 3D print, mean a great number of existing components can be designed for decentralised 3D printing, plus whole new components and add-ons developed, and thereby, through the ready variability of 3D printing, allow for an ever greater personalisation of a mass market product than is currently the case. The Simson Mokick is in many, all, regards more a framework for a motorbike than a motorbike. Uni_Zebra doesn't get that. Uni_Zebra makes it a definitive. With options for decoration.

We've noted before, and we fear we will have to again, the Simson Mokick is a very interesting and informative piece of design, not just in explaining Karl Clauss Dietel but in allowing one to approach understandings of what design is and can be, on the responsibilities of designers to society, arguably is one of the more important motorbike designs, also in context of going forward and the demands that will be increasingly placed on designers and manufacturers in responding to the myriad challenges we'll increasingly face. Yet is a work all too often reduced to an object, to a DDR "Icon". Or even worse a "Cult" object. As it essentially is with Uni_Zebra where Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph don't even get a mention. ¿Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph? ¿Who they? Which probably explains Uni_Zebra. And underscoring that it's not just in the former kapitalistisches Ausland that design in the former DDR needs to better appreciated, but also in the former DDR.

Arranged as a temporary village on the spot where the ZDF@Bauhaus stage once brought eternal shame on Bauhaus University Weimar, we will get over 2019, honest, and taking it's title from Timothy Morton's concept of Hyperobjects i.e. realities distributed in time and space to such a immense degree that we are unable to fully grasp them in their completeness, only as we meet them at any given moment, the project Hyperobjekte, challenged students to develop methodologies and frameworks to enable us all to better approach and challenge our myriad Hyperrealities.

Reflections undertaken by students from across four departments which brought forth projects such as, and amongst many others, Lass Los Nimm An by product design student Ronja Kügow which concerned itself with that eternal, permanent, moment when not only the now becomes the past but the future becomes the now; visual communication student Lino Ehrenstein' posing of the question Welche Richtung hat Gebüsch?, Which Direction have Bushes? and by extrapolation asking Which Direction has Life?; Spannunsfelder by art pedagogy student Liv Eichner whose jumble of threads visitors were invited to re-tie, re-connect, re-jumble, reminded very much that 'tis a tangled web we weave. And not only when we practice to deceive, although that inarguably is the key problem, but in whatever we do. And reminds that we do all weave that web. For ourselves, and for others.

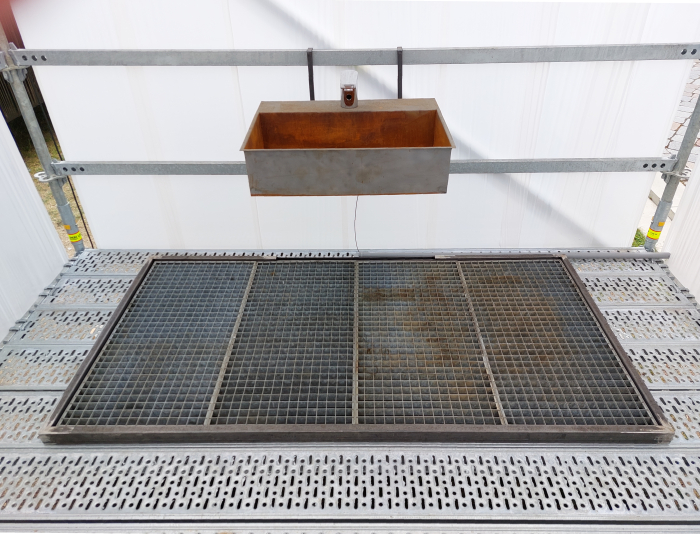

And also Dealing With Water by product design student Michel Schneider which sought to allow differentiated insights into our relationships with water, and which was greatly aided and abetted in its seeking by the Powers at the Bauhaus Uni Weimar who banned Michel's planned continuous stream of water seeping away into the earth by way of comment and reflection on both our unthinking use of water and the fragility of global water supply. According to Michel Schneider, and we don't know, we weren't there, we've only got his public announcement to go on, the deliberately wasteful cascade was banned partly because the Uni "was worried about negative headlines", which tickled us, for, and lest we forget, back in the day art schools lived on negative headlines, got their energy from, understood their raison d'etre as, negative headlines. And banned partly because the Uni didn't want to be associated with a squandering of public finances or a wasting of water. The latter of which Michel took as an incentive to compare the water usage in his project with the water demand of producing a kilo of beef for the Uni Mensa - the latter needs 25% more - and which should inspire all to question the water budget of the Bauhaus University Weimar with its innumerable ateliers, and to question the water budget for ZDF@Bauhaus, to measure the carbon footprint of ZDF@Bauhaus. And thus a banning that allowed and allows for a great many more roads of enquiry than would have been so readily accessible had the Uni not intervened.

As does Michel Schneider's argument that artistic freedom should have had priority. Really? Always? Or put another way, what we don't understand is why he couldn't recycle the water? Yes, it would have completely undermined the concept, we get that; but, in an age where we all understand that resources are finite, and in all probability not ours, an ownership issue reflected on just a few metres away in Prometheus Erbe by art pedagogy student Sebastian Günter, does art not have a responsibility to objectively consider, and if necessary adapt, the resource usage of its attempts to disrupt, question, reflect, expose, support, encourage, et al contemporary society? Is an art that is deliberately wasteful part of a meaningful approach towards solutions? Or an egotistic part of the problem? ¿L’art pour l’art and sod the planet? Recycling needn't mean the same water continually flowing through the system, it could, for example, be collected and used as grey water elsewhere, for example for watering those many gardens in the care of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, whose rising water use and associated rising costs are also worthy of intensive questioning. Yes, if the public knew the water was being recycled that would open arguments and discussions contrary to those intended and would minimise the impact; and if the public didn't know then that would be dishonest, which art can't afford to be, unless its dishonesty is its position. Recycling would have an impact on the installation, but pouring 12,000 litres of water down the drain in the name of artistic freedom, can't be right. Can it? Or can it? And can distributing 12,000 litres of water over Goethe's garden be right? Or using 15,000 litres to produce a kilo of beef?

And thus much as we would have enjoyed Michel's installation in its intended form, as realised it was inarguably much more informative and entertaining.