5 New Architecture & Design Exhibitions for November 2022

We published our first monthly list of exhibition recommendations on November 1st 2013, one of those short, superficial, posts we used to compose, having as we did back then endless time on our hands; and an intervening nine years that means that with this list for November 2022 we are entering our tenth year of helping you advance your cultural education.

While being very much aware that the vast majority of you have never visited a single one of the circa 450 new exhibitions we’ve carefully and conscientiously selected for your delectation, nor indeed have the vast majority of you visited any architecture or design exhibition in the past nine years: that the vast majority of you have chosen to neglect your cultural education. However, one of the joys of the museum exhibition as a format for elucidation, exploration, energising and entertainment, the reason we don’t give up on you all, is that, the next opportunity is always approaching.

Thus, while that which you have missed is gone for ever, and you’ll just have to try to catch up as best you can; that which is still to come is an opportunity waiting to be grasped. And in November 2022 there is an unusually large and varied amount of opportunities to grasp; the global architecture and design museum community unleashing a plethora of diverse new showcases.

And a plethora of new exhibitions opening in November 2022 that we were simply unable to narrow down to five. It would also have felt unjust given how many new showcases there are.

Our five six new opportunities to advance your cultural education in November 2022 can be found in Leipzig, Edinburgh, Winterthur, Berlin, New York and Vienna…….

“Deep-seated. The Secret Art of Upholstery” at the GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Leipzig, Germany

For all that the (hi)story of furniture design is one of developing and evolving formal understandings and positions to the function of furniture in ever new cultural, social, economic et al realities, its is also a (hi)story of developments in materials and processes: an all too often ignored component of furniture design that the GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig aim too illuminate, expose, with Deep-seated, The Secret Art of Upholstery.

Promising a presentation of some 100+ items of upholstered furniture from across the past 400 years, alongside some 70 examples of upholstery fabric and passementerie from the past 500 years, Deep-seated aims to, literally, go beyond the exterior and explore the interior of a genre of furniture that although defined by how it is constructed is all to often understood as how it looks. A how it is constructed, a changing and developing how, whose exposing should allow for better understandings of the relationships between contemporary furniture and contemporary society, of the relationships between developments in the manner by which furniture is constructed and the formal and functional developments of furniture, formal and functional possibilities of furniture. And which should also offer an opportunity to reflect on the role of craft in design, of craft as being not just a source of inspiration for designers, but a crucial component of design.

In addition, and very pleasingly, visitors to Deep-seated will be actively invited to try out examples of different upholstered furniture, to do that which museal furniture exhibitions normally actively prevent you from doing, and thereby enabling an appreciation through experience of what the different upholstery methods and materials mean in practice; while a presentation of 20th century upholstered furniture objects by the likes of, and amongst a great many others, Renate Müller, Peter Behrens, Liisi Beckmann, Ron Arad or Anton Lorenz should allow insights in to the reality that for all the easy manner with which we all employ the term “upholstered furniture”, it is anything but an homogenous genre.

Deep-seated, The Secret Art of Upholstery is scheduled to open at the GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Johannisplatz 5–11, 04103 Leipzig on Thursday November 24th and run until Sunday March 26th. Further details can be found at www.grassimak.de

A mid-1960s upholstered chair by Nanna Ditzel, part of Deep-seated. The Secret Art of Upholstery, GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Leipzig (photo Esther Hoyer, © and courtesy GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig)

“Bernat Klein: Design in Colour” at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland

Born in Senta, then Yugoslavia, today Serbia, in 1922, Bernat Klein broke with the orthodox Judaism of his youth in 1940 and enrolled in the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, Jerusalem, before post-War moving to England to study Textile Technology at Leeds University and subsequently on to Scotland, simply to work in the textile industry, but, as it turned out, to initiate a small revolution in the Scottish textile industry of the 1960s and 70s.

A small revolution that as the title of the National Museum of Scotland’s new exhibition tends to underscore was primarily, though not exclusively so, led by colour. Whereby less Klein’s use of colour as his by understandings of our relationships with colour, by his positions on the role and function of colour and for all by his production of colour: Bernat Klein being very much a textile designer who underscores that textile design isn’t the artistic creation of pretty patterns, but is an interplay of materials, technology, innovation, economics, traditions, functionality, sociology, artistic positions, etc to enable the realisation of contemporary meaningful pretty patterned textiles which others can use as they wish.

A small revolution that saw the sleepy universe of Scottish textiles become internationally relevant and offered the chance to redefine itself for coming society.

A small revolution that was relatively short lived, as Klein developed in new directions and became increasingly active in other areas, the Scottish textile industry quickly reverted to its shortbread tin, tourist gaze, understanding of itself; and then wondered why it shrunk and shrunk and shrunk and shrinks.

By way of marking what would have been Bernat Klein’s 100th birthday, the National Museum of Scotland promise with Design in Colour a presentation of not just textiles developed by Klein, and which as such embody the positions and approaches of Bernat Klein and should help elucidate his ongoing relevance, but also examples of how his textiles were used in clothing and domestic contexts, alongside examples of his art work, works that are intimately related to his textiles, and an elucidation of his contribution to the, again short-lived, introduction of Brutalist architecture into Scotland. And which should therefore allow not only for an introduction to a most interesting and informative textile designer and post-War Modernist, but also for differentiated considerations on textiles, textile design, design. And the recent (hi)story of the Scottish textile industry.

Bernat Klein: Design in Colour is scheduled to open at the National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, EH1 1JF on Saturday November 5th and run until Sunday April 23rd. Further details can be found at www.nms.ac.uk

Loch Lomond by Bernat Klein (1960, almost certainly mohair, but is not stated on the image file), part of Bernat Klein. Design in Colour, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh (photo © and courtesy National Museums Scotland)

“The Bigger Picture: Design – Women – Society” at the Gewerbemuseum Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland

There is always something particularly exciting when a museum take on an exhibition curated by another museum and extend and expand it; for all when they bring local, national, aspects and protagonists into the theme, the subject, and in doing so not only underscore the relevance of a macro subject at the micro scale, but also allow an opportunity for wider discussions, and thereby can help initiate new research paths, new understandings and new appreciations that weren’t visible, weren’t possible, at the project’s conception.

Something the Gewerbemuseum Winterthur should manage with The Bigger Picture: Design – Women – Society, an exhibition which will extend the Vitra Design Museum’s exhibition Here We Are! Women in Design 1900 – Today in a Swiss context. And that not just through the presence of creatives such as, and amongst others, Lux Guyer, Margrit Linck, Rosmarie Baltensweiler or Sarah Harbarth, but also through discussions on publications such as the magazine Emanzipation, a publication that between 1975 bis 1996 was an important organ in feminist, gender equality and societal discourses in Switzerland. And a magazine whose presence indicates that as with Here We Are! The Bigger Picture‘s focus will be very much on the social and cultural structures, conventions and frameworks in which design exists and is understood, rather than works and biographies as such. A focus that the Gewerbemuseum Winterthur, as the title neatly implies, aim to extend beyond the myriad subjects of ‘women and design’ and into more general considerations on design, inclusion and diversity.

And which in doing so should not only allow for a deepening of the discourse on contemporary design, on contemporary design’s relationship(s) with contemporary societies, but also allow for valuable new insights into the (hi)story of design in Switzerland, and for all how that (hi)story is popularly retold, and of the skews and errors in that retelling.

The Bigger Picture: Design – Women – Society is scheduled to open at Gewerbemuseum Winterthur, Kirchplatz 14, 8400 Winterthur on Friday November 25th and run until Sunday May 14th. Further details can be found at www.gewerbemuseum.ch

Futuress. Feminist Platform for Design Politics, part of The Bigger Picture: Design – Women – Society, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur (photo © Maria Júlia Rêgo, courtesy Gewerbemuseum Winterthur)

“Magyar Modern. Hungarian Art in Berlin 1910–1933” at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, Germany

For all that popular understandings of inter-War creativity in Europe often, and with good reason, focus on Germany, only rarely do they focus on the fact that not all those in inter-War Germany were Germans. Inter-War Germany was very much a meeting point for inter-War European creatives. For all inter-War Berlin was very much a meeting point for inter-War European creatives. And among the many nationalities who played an important role in the developments of the period, and helped make Berlin such an important creative centre, Hungarians hold a particularly notable position.

A position the Berlinische Galerie aim to explore and elucidate in Magyar Modern, an exhibition whose understandings of the Art of its title isn’t just the painting and sculpture as practised by the likes of, for example, Lajos Tihanyi, Béni Ferenczy, János Mattis-Teutsch or the various members of the group Nyolcak, The Eight, but also the architecture of a Fred Forbát or Oskar Kaufmann, and the photography and film-making of a Martin Munkácsi, Eva Besnyő or László Moholy-Nagy. If sadly not, as far as we can see, inter-War furniture; though through the personages Kálmán Lengyel, Anton Lorenz and Marcel Breuer bent steel-tube furniture is very much a (hi)story of Hungarians in inter-War Berlin.

Promising a presentation of some 200 objects from across a range of creative genres, Magyar Modern should not only help many of the protagonists find a new, international, audience and thereby allow them to increase their contribution to contemporary discourses, but also help elucidate both the importance of Berlin’s international community, of Berlin’s cosmopolitan character, as a driver of inter-War creativity, and also the role of eastern Europeans in the development of creativity in Europe, a role that all to often gets lost, as can eastern Europe in general, through popular foci on western Europe and Russia.

Magyar Modern. Hungarian Art in Berlin 1910–1933 is scheduled to open at the Berlinische Galerie, Alte Jakobstraße 124 – 128, 10969 Berlin on Friday November 4th and run until Monday February 6th. Further details can be found at https://berlinischegalerie.de

Lajos Tihanyi, Großes Interieur mit Selbstbildnis – Mann am Fenster, part of Magyar Modern. Hungarian Art in Berlin 1910-1933 Berlinische Galerie, Berlin (Photo, Museum der Bildenden Künste – Ungarische Nationalgalerie, courtesy Berlinische Galerie, Berlin)

“Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves” at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, New York, USA

As not just the designer of the entrances to the Paris Metro stations, but in many regards the developer of the identity of the Paris Metro, that essential, indispensable, component of downtown Paris, that motif that every tourist leaves Paris with at least one photo of, Hector Guimard is inarguably one of those creatives most popularly associated with the flowing florid dynamic of French Art Nouveau, is one of the creatives who helped bequeath French Art Nouveau its particular dialect.

If a flowing florid style found at the entrance to urban transport hubs that does tend to strictly define Hector Guimard.

Yet Hector Guimard was, as the Cooper Hewitt, New York, aim to elucidate, an awful lot more.

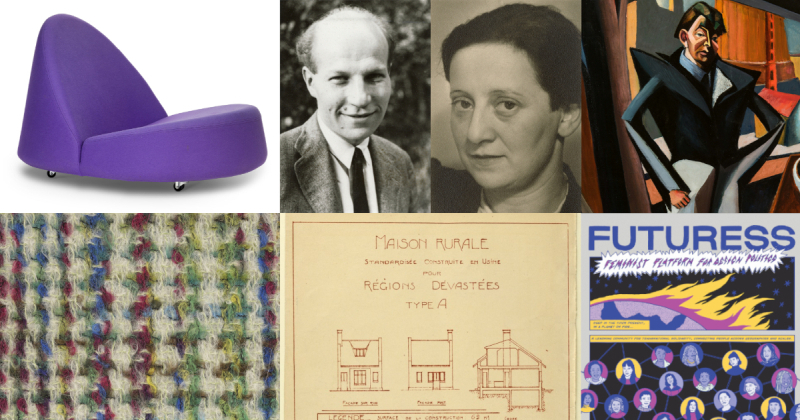

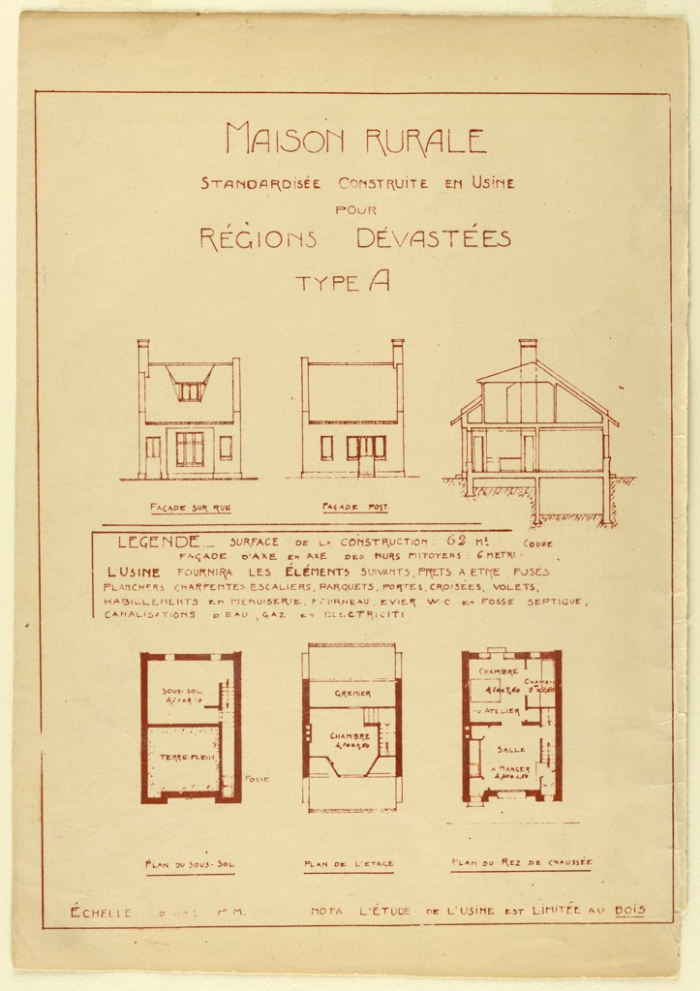

He was also, for example, a series of inter-War standardised, pre-fabricated housing concepts.

Standardised, pre-fabricated housing that was inarguably a response to the opulent villas a Hector Guimard built as a young architect in the late 19th century; standardised, pre-fabricated housing that reminds that his 1900-1904 Metro entrances are, for all their florid excesses, a series of standardised designs created from prefabricated components, are very much industrial. And thus standardised, pre-fabricated inter-War housing that allows one to understand Hector Guimard not just as an Art Nouveau architect but as both an architect who developed and evolved in context of his time, and also as a mediator on the path from Historicism to Modernism.

Promising….. we’re not entirely sure, the Cooper Hewitt are always very, very reluctant to give away any information in advance of an exhibition opening, preferring to keep everything as vague as possible, presumably for fear that people may visit the exhibition……. however, as best we can ascertain, How Paris Got Its Curves should present in addition to documents and archive material relating to Guimard’s standardised, pre-fabricated housing projects, a collection of objects and materials from across the decades of his work, and across the many genres he worked in, including, yes, some florid Parisian cast-iron, and thus should provide for an introduction to Hector Guimard far beyond the Paris Metro. And thereby should also help better place Hector Guimard on the helix of architecture and design.

Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves is scheduled to open at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2 East 91st Street, New York, New York 10128 on Friday November 18th and run until Sunday May 21st. Further details can be found at www.cooperhewitt.org

Plans for a standardized rural house by Hector Guimard, part of Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum New York (Diazo print, gift of Madame Hector Guimard, image © and courtesy Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum)

“Atelier Bauhaus, Wein. Friedl Dicker and Franz Singer” at Wien Museum MUSA, Vienna, Austria

For all that Bauhaus is popularly reduced to a few names, a few objects, and a few buildings, it is and was an awful lot more. Most of which was realised post-Bauhaus. Most of which has become forgotten for a host of reasons. A state of post-Bauhaus forgetfulness which invariably tends to reinforce the popular image as a definitive and thereby prevents one reaching other aspects of Bauhaus.

Other aspects such as Friedl Dicker and Franz Singer. Two Vienna natives who having studied at Johannes Itten’s private art school in the Austria capital followed Itten in 1919 to Weimar and Bauhaus, before establishing a joint office, initially in Berlin, subsequently in Vienna. A joint office from which they developed and realised innumerable furniture and interior design projects, and the occasional architecture project; projects very much in context of the avant-garde, Modernist, Functionalist, positions of the period, projects which, to paraphrase Wien Museum, arose from Atelier Bauhaus, Wein. Before the rising Fascism and the approaching Second World War, saw Singer emigrate to England and Dicker to Czechoslovakia, where in 1942 she was detained by the Nazis, who in 1944 murdered her in Auschwitz.

A war, and a Fascism, and an anti-Semitism, that not only cost Friedl Dicker her life, but also saw much of Dicker and Singer’s work destroyed; a process continued in the post-War rebuilding of Vienna, and which aided and abetted Dicker and Singer’s fall into their contemporary relative anonymity.

An anonymity from which Wien Museum hope to free them via a presentation of models, photographs, sketches, and the occasional physical object, some of those rare works that have survived to this day, and which should help not only allow access to the biographies, works, approaches, and relevance, of Friedl Dicker and Franz Singer, allow them to regain their visibility, but also allow for more probable appreciations of the (hi)story of design in Austria. And more probable approaches to the question of what was Bauhaus? What is Bauhaus?

Atelier Bauhaus, Wein. Friedl Dicker and Franz Singer is scheduled to open at Wien Museum MUSA, Felderstraße 6–8, 1010 Wien on Thursday November 24th and run until Sunday March 26th. Further details can be found at www.wienmuseum.at

Tagged with: Atelier Bauhaus, Bauhaus, Berlin, Berlinische Galerie, Bernat Klein, Cooper Hewitt, Deep-seated, Design in Colour, Edinburgh, Franz Singer, Friedl Dicker, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur, Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Hector Guimard, Here We Are! Women in Design 1900 – Today, How Paris Got Its Curves, Hungary, Leipzig, Magyar Modern. Hungarian Art in Berlin 1910–1933, MUSA, National Museum of Scotland, New York, The Bigger Picture: Design – Women – Society, Upholstery, Vienna, Wein, Wien, Wien Museum, Winterthur