As we all know from the 1st Law of Thermodynamics, energy cannot be created nor destroyed, only transformed from one form to another.

And as a species we've developed a myriad ways of transforming one form of energy to another.

We burn oil.

We burn coal.

We burn gas.

We burn wood.

We burn an awful lot, don't we.....

But we also employ, for example, the kinetic energy of wind, waves and photons or the potential energy of Uranium atoms.

With Transform! Designing the Future of Energy the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, focus less on the physical and chemical transformations of energy, as on transformations in how we source, supply and use energy.......

According to the Vitra Design Museum there are and were three primary motivations for initiating Transform! Designing the Future of Energy, two pertinent, pressing, real world, stimuli and one institutional context.

The first two can be summarised as: the increasingly tangible consequences of our long standing dependency on fossil fuels, that burning of things we're all so partial to, with the associated question of how, if, we can break that dependency; and the Russian attack on Ukraine with its associated exposure of the fragility of contemporary global energy supply networks in context of fragile geopolitics, with the associated question of how, if, we can restructure, re-imagine, energy generation and distribution systems.

Hows and ifs the Vitra Design Museum, being as it is a design (and architecture) museum, very naturally, self-evidently, framed in context of the role and function of design in questioning the existing, in exploring alternatives, and in providing practical solutions, as indeed design, inarguably, has provided solutions on the path thus taken; solutions which have helped both get us all this far and also gotten us all into our current predicaments.

Hows and ifs of design in context of energy, with the myriad whys, wherefores and whos that invariably arise in such considerations and research, that became Transform! an exhibition, an exploration, a discussion, in four chapters.

A discussion, an exploration, an exhibition opening with Human Power, a chapter less directly focussed on the power of humans, although that said it does feature an intervention by Karlsruhe based designer Thomas Rustemeyer in conjunction with Tweaklab, Basel, involving three bicycles and the challenge to generate via cycling the 0.3 Wh required for a Google search query, the 18 Wh required for a smartphone charge, the 65 Wh required for 5 minutes of film streaming or the 333 Wh for a 1 minute hot shower, and which is a very neat, very satisfying reminder, that energy needs to be generated, transformed, to be practically available, isn't just there; while Rustemeyer's hint that "you can achieve your goals faster by joining forces!" is just one of numerous pieces of good advice contemporary society seems resilient to, to be found throughout Transform!

And a challenge to produce the energy to power contemporary digital society, and our showers, which also reminds of the contemporary, very large, need for power for humans, the primary focus of the opening chapter, in many regards a thread running through Transform! A need explored through its consummation; an exploration that, in effect, begins with the rise in the relevance of, and our dependency on, oil since the 19th century, and thus that, along with coal, defining source of energy of the most recent decades of human society. Albeit sources that not only brought prosperity but a great many problems, prosperity and problems not always present in the same global regions, nor always equally shared amongst the residents of our planet, human and non-human; problems that, arguably, since the 1960s, if at first imperceptibly sluggishly, and only really picking up speed since the start of the 21st century, have led to protests, activism, and demands for alternatives.

Alternatives approached in the subsequent three chapters of Transform!

Alternatives approached in context of Energy Tools with its presentation of design projects both speculative and practical which re-imagine existing human tools in context of alternative energy sources, and/or contemporary realities, or which propose novel tools; projects such as, and amongst many others, the so-called (B)pack project by Neuhäusel based company (B)energy, essentially a large, yet very light, biogas filled rucksack which offers an alternative to wood and charcoal as a cooking fuel in off-grid rural areas, and thereby also helping reduce deforestation with all the benefits that has for the wider environment; Groundfridge by Floris Schoonderbeek, a project which, as the name neatly implies, is a fridge in the ground, a ca. 3000 litre fridge in the ground, thus more a communal fridge than a private fridge, and for all a fridge that requires no electricity to cool its contents, rather employs the constantly cool ambient temperature of the ground in which it sits. And a project which not only reminds that a few years ago you couldn't visit a student graduation exhibition without meeting an analogue, off-grid, domestic fridge project, often ceramic based, and invariably also meeting a project to encourage home mealworm production by way of enabling greater food self-sufficiency, but also reminding that back in the day underground cellars were the preferred way of keeping foodstuffs cool before electricity came along and brought new possibilities. And new problems. And thus a fridge in the ground which tends to underscore that we, that designers, that design, don't always need to reinvent the wheel, just need to consider that done in the past in contemporary contexts, tends to underscore a Kaare Klint's admonishment that "Problemerne er ikke saa nye, de er i mange Tilfælde løst før"1, "the problems are not so new, they have in many cases been solved before". If in different contexts with different materials and different technology.

A truism also expressed in Transform! via Harvest/Cooling by Arvid Riemeyer, essentially a vest with plastic fins that create a gap between shirt/t-shirt/blouse and the skin and thereby provide for air exchange and cooling on warm days, and a 21st century German vest which finds an echo in the 19th century Korean rattan vest as seen in All Hands On: Basketry at the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, and which was similarly intended to provide for air exchange and cooling on warm days. If Arvid's vest does appear the more practical and comfortable solution. Assuming that is it can be washed without the blade-esque fins tearing the rest of your clothes to shreds. Then rattan would be better.

Alternatives further approached in the chapter Transformers with its focus on the construction and mobility sectors which, according to the curators, who we don't doubt, account for some 60% of global energy consumption, which is an outrageous contribution. And in itself a number worthy of, demanding of, serious consideration, and a fundamental questioning: How much!!! Why!!!

Alternatives approached, explored and introduced in context of construction via projects such as, and amongst others, the so-called PlusEnergie-Quartier P18 in Stuttgart by Werner Sobek and AH Aktivhaus, a project completed in 2023 that, by all accounts, is the largest sustainable housing estate in Germany, and which aside from the energy and resource saving considerations, and the plans for a future recycling, inherent in its design and construction, generates, thanks to its numerous innovations and array of technology, more energy than it uses, even if we would note that Transform! makes no reference to how the construction costs compare with more conventional projects nor the final square metre price of the apartments; or C.F. Møller Architects' 2020 Copenhagen International School project, a construction whose facade is, essentially, composed of some 12,000 solar modules, modules slanted at varying angles and incorporating varyingly coloured glass, thus a facade that is not only active in its interplay with light and viewing perspectives, perceptions, form, but actively generates half the school's electricity demand. And a C.F. Møller Architects who trace their history back to a practice established in 1928 by Christian Frederik Møller and Kay Fisker, Fisker being one of the early protagonists, earliest advocates, in Denmark of Functionalist Modernist architecture positions, and an important early influence on an Arne Jacobsen.

And thus a C.F. Møller Architects who lead one very naturally to considerations of undertaking an energetic comparison of the Copenhagen International School with not only Jacobsen's late 1950s Munkegård school, Copenhagen, but also with Møller and Fisker's 1930s Aarhus University campus, projects very much embodying contemporary positions and materials and thus a century embracing comparison which, we'd argue, can, should, help elucidate how as we understand things better in context of the passage of time, the certainties of the past can, occasionally, become errors, see also the asbestos met in Perfectly Imperfect – Flaws, Blemishes and Defects at the Gewerbemuseum, Winterthur, and which was supposed to improve the heating efficiency of buildings. Before it became highly carcinogenic.

Which all reminds of a Søren Kierkegaard's position that while life must be lived forwards, it can only be understood backwards, that insufferable reality within which the contemporary decisions on energy sourcing and supplying, the hows, and ifs, of breaking our dependency on fossil fuels, the hows, and ifs, of restructuring energy systems, discussed in Transform! need to made.

And alternatives approached, explored and introduced in Transformers in context of mobility by, and amongst other examples, a brief discussion on solar cars, a discussion within which the so-called Covestro Sonnenwagen constructed in 2019 by a collective of students from the RWTH Aachen and FH Aachen, a.k.a. Team Sonnenwagen Aachen, is juxtaposed with 1950s solar powered cars, including a press release from General Motors announcing the demonstration of a ""sun powered" model automobile believed to be the first ever built" and which was to be presented in the Power for Progress show in Chicago in the autumn of 1955. Yes, yes!, that General Motors who, as we all recall from the discussions on Tsuyoshi Tane's Garden House in the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, and on the Vitra Campus, informed us all in context of their Futurama II immersive installation at the 1964 World’s Fair that "in warmer seas are new realms of pleasure". Yeah. Warmer seas. Brilliant. Bring 'em on.🙄

Not that with their "sun powered" cars GM were embracing, championing a fossil fuel free future, the sort of fossil fuel future that could have spared us the tragedy of warmer seas; rather, and, arguably, true to 1950s form, Power for Progress was but a component of the so-called Powerama event, a show intended to "dramatise the importance of Diesel [sic] and aircraft power in our modern economy" and that Power for Progress "will also give visitors dramatic and easy-to-understand demonstrations of the fundamentals of Diesel [sic] and gas turbines".2 The regularity of making Diesel a proper noun tending to underscore, alongside 'Diesel and gas turbines' as 'Power for Progress', where GM's priorities, and future, lay. And that the "sun powered" car was but a PR gimmick. Thoughts reinforced by the press release noting that "GM officials emphasised that solar power has no practical application in the automotive industry at present". But could it today had GM done more then? Would there be a need today for Team Sonnenwagen Aachen had GM done more in the decades since 1955? And what do GM officials think about solar powered cars today? And do they still believe diesel is a proper noun?

Transform! ends, as an exhibition, with Future Energyscapes, a chapter which, in many regards, deals with subjects and themes related to those introduced in Transformers, concerned as it is not just with novel energy generation and distribution concepts and systems, but also, and importantly, with the integration of such into urban and landscape planning; future energyscapes discussed via, for example, Energy Shapes the City a project developed for Transform! which discusses climate friendly urban planning concepts and approaches as exemplified by the development of the Dreispitz area of Basel, a project realised in a cooperation between the agencies Transsolar, Urban Catalyst and Bauhaus Earth, and a project which stands on the upper floor of the Gehry Building like some futuristic communication tool, which if it was would inevitably require a lot of energy and rare earths; or via the Filtration Skyscraper project by San Francisco based architect Honglin Li which envisages using the decommissioned oil rigs of a post-fossil fuel future to clean the oceans of the pollutants and toxins the fossil fuel age put in them, less swords to ploughshares as drilling rigs to molluscs. And which seems only fair. If a very, very long job.

Or a selection of (hi)storic visions of energy generation and supply, potentially Utopias that's a subject for another day, including, for example, Hermann Honnef's plans in the 1930s for a network of Windkraftwerke, Wind Power Plants, to provide power for Germany in context of the, then, recognised finiteness of fossil fuels, Wind Power Plants that formally resemble, if one so will, functional Russian Constructivist towers, thus very much in context of their age architecturally if far ahead of their age conceptually, and which in their enormity bear no resemblance to the wind turbines of today. And a selection that also includes a reminder that the EU began, as noted from At the coalface! Design in a post-carbon age at the Centre for Innovation and Design at Grand-Hornu, as a Coal and Steel Community, origins in energy generation and supply that the current EU leaders may, potentially, do well to reflect upon as they lay the path of the Union and its citizens into a future in which energy questions will be more prevalent, more urgent, than they were in the 1950s. And steel and heavy engineering, arguably the real heart of the community in the 1950s, a lot less relevant.

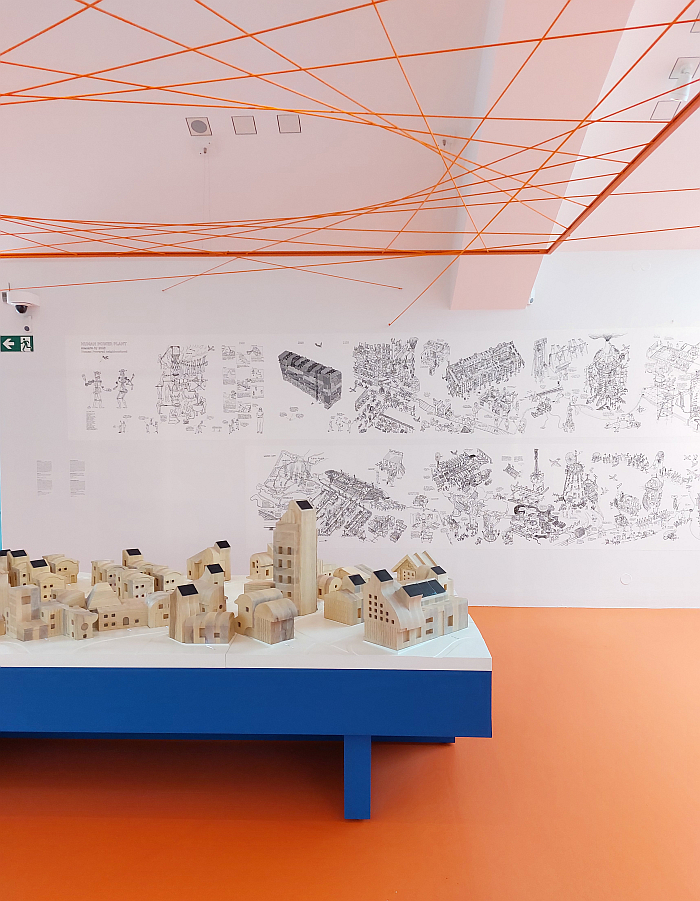

And also discussed via the mural Human Power Plant by journalist Kris de Decker and artist Melle Smets which introduces you to daily life in the Bospolder-Tussendijken neighbourhood of Rotterdam in the year 2050, a climate neutral 2050 Rotterdam; and a mural, an imagined daily life in 2050's Rotterdam which, as the curators note, asks would a modern society that only uses human energy be conceivable?

A question posed at the end of Transform! that takes you back to the bicycles of the opening chapter, bicycles added to in Human Power Plant by a harnessing of the kinetic energy of children, and adults, playing on swings, a reminder that we don't just waste that energy produced but waste energy in that we don't employ it, much as a Seneca teaches us we waste those years on earth given to us. And a question one very naturally extends with an: and if not, why not?

And if we can't, which we probably can't, or more accurately don't want to, that's why we buy e-bikes rather powering a bike with our own energy, we're not interested in a human power based society...... how do we power modern, and for all future, society?

As an exhibition Transform! very much takes the position that future society should, must, be powered by non-fossil fuel energy, answers the hows and ifs of the initiating stimuli with local level, non-fossil fuel energy; is very much not only an argument for the feasibility of a fossil fuel free future, but a 3D essay on why that is desirable, necessary, essential. A position tending to be underscored by the demand, the insistence, inherent in the ! of the title.

A ! that for others is a ?

Energy sourcing and supply isn't just a question of physics and chemistry and engineering and design, it also involves politics and economics, and in terms of the latter two there are a great many who take a diametrically juxtaposed position to the Vitra Design Museum, for example, a Donald Trump Digs Coal, and he isn't alone. While Rishi Sunak is determined to suck every last drop of oil out of the North Sea. To the delight of a great many.

And even amongst those who support the Vitra Design Museum's position there are fundamental differences on how our future energy supplies should be realised and met; differences pleasingly highlighted in Transform! by a collection of posters and placards from across recent decades in which campaigners and activists both call for more atomic energy and for no atomic energy, call for more wind power and for no wind power, in context of the latter viewing the images of Hermann Honnef's monstrous Constructivist Wind Power Plants you can physically sense the resistance, physically sense the utter outrage, that would arise would they be proposed today; anyone opposed to contemporary wind turbines would never accept a Honnef Windkraftwerk. Nor would a great many of those who accept contemporary wind turbines.

Yet regardless of your personal position we all want not only 0.3 Wh electricity for a Google search query, 18 Wh electricity for a smartphone charge, 65 Wh for 5 minutes of film streaming, but also want all the Wh required for a hot shower longer than 1 minute, for an autonomous vacuum cleaner, for an air fryer, an app to turn our living room lights on and off, to post videos of our toast on social media, a skiing holiday in a snowless region, a flying car, chats with Siri, Alexa, Bixby et al, strawberries in Europe in February, to have our new smartphone delivered by a drone in less than an hour, new clothes every six months that look like them on social media, VR headsets, etc, etc, etc. And so how do we power all that?

Thoughts, and a presentation in the Vitra Design Museum, which help focus ones attention on the undeniable fact, if a fact we all permanently deny, that the future of energy isn't just a question of how we source energy and how we supply energy, but how we use energy.

Helps focus ones attention on the undeniable fact, if a fact we all permanently deny, that the primary transformation must be in our relationship with energy, individually and collectively.

Must primarily be a social transformation rather than a chemical or physical transformation.

As one can read in Transform!, in 1940 Richard Buckminster Fuller calculated that global human society used 17 times the energy it could produce through human power alone, and the distribution of that usage wasn't equal; when he recalculated in 1953 global human society used 38 times the energy it could produce through human power alone, and the distribution wasn't any more equal.

And today?

Bucky may no longer be with us to do the math, but we all know that in terms of energy consumption we live, as with all our human devised systems of existence, not only in a reality of very unequal global distribution but of overconsumption in Europe. And North America.

And while we don't have to live à la Kris de Decker and Melle Smets' Bospolder-Tussendijken 2050 Utopia, a word we use deliberately, and indeed when one considers that in 1940 we were already a long, long way from that vision of a 2050 Bospolder-Tussendijken, were in a location from where the path back was as likely as that of a William Morris's from late 19th century London to the Nowhere he briefly visited, we do need to live differently.

Do need to head Bucky's admonishment in 1969, in 1969 language, that 'man', "... thinks he has infinite room to dispose of all pollution and infinite resources to be brought into play as he exhausts first one then another. But he is wrong. His reflexes are self-annihilatively conditioned. Earth is a closed system."3

And if Earth is a closed system, and regardless of whether it is or isn't it is informative and instructive to think of it as one, the 1st Law of Thermodynamics applies: we have a finite amount of energy. And while that energy can't be destroyed, it can be wasted, that energy which we use for one thing can't be used in the same instance for another, but must be subsequently reconverted in order to be made available again, and the thus inherent necessity to be consciously aware of why and wherefore we use energy.45

Which tends to lead one to an argument that the key going forward is a reduction in our energy consumption, individually and collectively.

In which context, in the accompanying catalogue, more so than in the exhibition itself, a discussion can be followed on efficiency versus sufficiency, an argument, if one so will, that transforming ever more of one form of energy to another can't be the answer if we then use the energy released wastefully, meaninglessly, frivolously. Something which not only brings one back to Seneca, but is something deliciously underscored in the opening chapter of Transform! via a photo by Mitch Epstein of the wind turbines of the Altamont Pass Wind Farm, California, one of the oldest and largest global wind farms, towering over two electric golf buggies. Is that really a meaningful use of the energy being produced? Really? In addition we'd note the pristine green and lush fairway in what is very obviously an arid region of a famously, and increasingly, arid California, and ask if, and very much in context of Water Pressure. Designing for the Future at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, is that really a meaningful use of water? Really?

And an admonishment also contained in the apparently innocuous, certainly very playful, and thoroughly engaging, Solar Do-Nothing Machine developed in 1957 by Charles and Ray Eames, a kinetic sculpture, a 3D kaleidoscope, that was an early illustration of solar power in action, and a commission Charles Eames noted they decided to accept because "a demonstration of solar energy as a practical source of power appeared to be a not uninteresting way of promoting resource conservation"6, and who could disagree.

Were it not for the fact that the Solar Do-Nothing Machine was commissioned by the Aluminum Company of America in context of an initiative, a PR campaign, not to promote resource conservation but to promote aluminium, a material, a resource, that not only requires obscene amounts of energy in its production, you'd have to spend a long, long time on Thomas Rustemeyer's bicycle intervention to generate the necessary Wh to smelt 1 kg of alumina, even for 1 gramme, but also, and as noted from Into the Deep. Mines of the Future at the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen, in the 1950s aluminium was being employed in America with an astonishing irresponsibility, a mind-numbingly thoughtless gay abandon; an America that couldn't meet its current needs for aluminium was dreaming of a future where, in effect, everything was aluminium, while disposing of no longer required aluminium, that aluminium that had achieved its marketing led planned obsolescence, in landfills, even though they knew bauxite supplies were finite and in far, far off lands. Lunacy. Grade A+ lunacy. That belief, to paraphrase Bucky, that we have infinite room to dispose of all pollution and infinite resources to be brought into play as we exhaust first one then another.7 That (hi)story of aluminium that allows it to stand as such a wondrous analogy for all irresponsible human consumption. And as an example of how resistant we all are to learning from the past.

A resistance that is not only one of the reasons the question Transition? or Transition! is currently so hotly debated, is able to be employed as a weapon in cultural battles, were we able to learn lessons it wouldn't even be discussed, but also means the question Reduce? or Reduce! is dismissed out of hand today as easily as Recycle? or Recycle! was in context of aluminium in 1950s America.

Yet much as looking back recycling should have been the focus then, shouldn't even have been a question then, so can an argument be made that reduction must be the focus, the objective, today.

And sufficiency not efficiency must be the objective in design and the future of energy.

An easily accessible and well-paced exhibition featuring a very satisfying mix of projects and positions and approaches, including, very pleasingly, a great many by young creatives of all genres, creatives, or at least some of whom, will, may, have an over-proportional say in the design of the future of the exhibition title and so whom its important we all get to know before they do, and young creatives who, and a lot less cynically, as young creatives are producing works based on their youthful experiences of the world, one untroubled by decades of position entrenching and who can therefore formulate questions and approach responses with an openness older creative simply can't, and which is, we'd argue very important as we navigate forward, Transition! very neatly and comprehensibly introduces important themes and concepts in context of contemporary and future energy supply, sourcing and use; can however on account of the scale and depth of those themes and concepts be but an introduction. But an invitation and admonishment to continue that begun in the Gehry Building on your own later. An invitation supported and encouraged by the accompanying catalogue which not only features a number of essays, and a comic strip, covering many of the themes involved in a lot more detail, but also features twice as many projects as featured in the exhibition, and thus is not only a genuine extension of the exhibition, but an interesting and informative and entertaining resource in formulating and approaching the necessary, and increasingly urgent, question and responses.

An exhibition which in its mix of hi-tech, lo-tech, and at times no-tech, solutions helps underscore that for all novel technology can be very helpful and phenomenally useful it isn't automatically always the best answer, doesn't necessarily have to be used just because it's possible, we have choices, options; and an exhibition which despite its obvious, unmistakable, position on the Transform? or Transform! question is never preachy, doesn't get all shouty like social media, but rather leaves you to approach the various themes in your own time and from our own perspective, in many regards encourages you to do that, doesn't offer answers rather presents examples, possibilities, arguments, and thereby challenges you, encourages you, to come to your own position on Transform? or Transform! Reduce? or Reduce! Sufficiency! or Efficiency! While all the time Søren Kierkegaard hovers in the corner.

And while it is always very rude to mention things not in exhibitions, we did miss a critical assessment by the Vitra Design Museum of their own energy consumption; a critical assessment of not just the energy used in the day to day running of the Vitra Design Museum and its various spaces and projects, but also in the processes of developing, constructing, presenting, marketing and touring its exhibitions. And not just a critical assessment of the Vitra Design Museum, but the whole Vitra Campus: as noted from Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House at Vitra Design Museum Gallery, one of the driving thoughts behind the Garden House was the position of Rolf Fehlbaum, Vitra's ex-CEO, long-term guiding light and initiator of the Vitra Design Museum, that after decades of industry ignoring nature, of industry ignoring the consequences of its actions on nature, change was needed and "now is the time to rethink nature on the Campus".8 Energy must be part of that rethink, and much as Garden Futures. Designing with Nature was an occasion to formally introduce the Oudolf Garden, so Transform! is and was an apposite opportunity for the Vitra Design Museum to explain how the various institutions resident on the Vitra Campus are rethinking energy on the Campus, of the transformation in terms of energy being planned and undertaken on the Vitra Campus, a transformation the Vitra Design Museum understands as ! But an opportunity sadly passed up. But which we hope will be taken at a later opportunity.

In addition we also missed Jevons Paradox. Something, admittedly, we wouldn't have known we'd missed had Jochen Eisenbrand, the Vitra Design Museum's Chief Curator, and lead curator on Transform!, not mentioned it ahead of the opening. But he did. And now we miss it.9 Formulated by the English economist William Stanley Jevons in the 1860s, Jevons Paradox, and summarising far more than is prudent, says that with increasing efficiency of coal use, consumption of coal increases. Which if you're trying to reduce your coal consumption isn't necessarily helpful. And while Jevons Paradox is, as with all such theories, open to debate, criticism, revision, and isn't necessarily always valid to the same degree in all situations and all moments in time, it's not as if its Murphy's Law, or the 1st Law of Thermodynamics, it is nonetheless, we'd argue, an important component of the Reduce? or Reduce! debate we're not really having, but which Transform! tends to admonish we need to have. An argument that the increased energy efficiency industry extols these days, and which any and all new electric based product will, invariably, claim to offer in its energy inefficient marketing, might not be helping in reducing our energy consumption. And that the only thing that can help is using less.

Or put another way, the percentage of the Copenhagen International School's electricity produced by its 12,000 solar modules might not increase if the efficiency of the technology the school employs increases, but it will increase if the school uses less electricity. Increasing the energy efficiency of household goods might not reduce the number of Honnef Windkraftwerke required, but using less energy in the home will. More efficient golf buggies might not reduce global golf's footprint, fewer buggies, and a lot more walking, will. PlusEnergie-Quartier P18 could generate, relatively, more energy if it used, actually, less. And you don't have to cycle so much on Thomas Rustemeyer's bicycle intervention if you only have one smartphone to charge.

Similarly, increased efficiency doesn't necessarily reduce the volumes of the ores, metals and rare earths required for our renewable energy systems, using less electricity does; nor does increased efficiency necessarily reduce the area of the planet needed for wind and solar and wave farms, using less electricity does.

A reduction in use which, and if energy involves not just physics and chemistry and engineering and design but also politics and economics, implies the necessity of not only transforming how we source and supply energy, how our buildings and transportation and tools use energy, but also transforming economics and politics. The latter of which being, inarguably, the more difficult. We're certainly not aware of all too many global politicians calling for a reduction in global energy use. Didn't here all too many calls in Europe to use the absence of Russian gas in the wake of the Russian attack on the Ukraine to reduce our energy demand, rather all we heard was the rush to secure new sources of fossil fuels to replace the missing Russian fossil fuels. Nor do we hear all too many European/American politicians calling for a fairer global distribution of energy.

And also implies the necessity of transforming ourselves, transforming our behaviour, transforming our personal relationships with energy. Arguably the most difficult transformation of all. For all in an age of digital Bling.

However, as Transform! Designing the Future of Energy exhibition and Transform! Designing the Future of Energy book allow one to better appreciate and understand, we are all sources of energy, we are all sources of power, it's all about how we use it, how we transform that potential energy within us all.

That we have all have the potential energy to design the future, its just a question of how we transform it.......

Transform! Designing the Future of Energy is scheduled to run at the Vitra Design Museum, Charles-Eames-Str. 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday September 1st.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.design-museum.de

In addition there is a catalogue in German and English featuring descriptions of some 100 global projects plus a collection of essays, and a comic strip by Belgian artist Guillaume Lion.

1Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 203

2General Motors Corporation, Press Release, Sunday July 24th 1955, as presented in Transform! Designing the Future of Energy

3Statement of R. Buckminster Fuller, Research Professor, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Ill, to the Senate Sub-Committee on Intergovernmental Relations, March 4th 1969, re-published in R. Buckminster Fuller, The World Game: Integrative Resource Utilization Planning Tool, 1971, page 13 Available via https://www.bfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/world_game_series_document1.pdf (accessed 27.03.2024)

4No, stop it, don't try to expand the system by bringing the Moon and Mars and Saturn in to the debate, we can't just go to the Moon and get Helium-3 for our nuclear fusion reactors, or whatever other ores, metals and rare earths we don't have enough of here on Earth. And even if we did it would all still be finite. And, yes, we do know why there are currently so many privately financed Moon missions being attempted and undertaken.

5And no, using more solar power doesn't solve the problem because a given area of photovoltaic cells can only produce a maximum amount of electricity, if you need more electricity you need a greater area covered, and we need surfaces for other things. Yes, you're right, if photovoltaic cells become more efficient we can produce more electricity from a given area, but if we use ever more electricity we will still need ever larger areas, areas we still need for other things. And we have to produce the photovoltaic cells with rare earths mined from the sea bed. Also lunacy. Problems of space and resource usage also inherent within wind or wave power. Only reduction of use is sustainable.

6Letter from Charles Eames to Ian McCallum, editor-in-chief of Architectural review, November 14th 1958, as presented in Transform! Designing the Future of Energy Also quoted, in a wider context, at Eames Office: Solar Do-Nothing Machine

7Worth noting that in the 1950s Buckminster Fuller developed his Geodesic Dome's on the basis of aluminium, sometimes that which can look so promising can come back and bite us. Which, yes, is an alternative formulating of Kierkegaard's position.

8Rolf Fehlbaum, quoted in the exhibition Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein, 18.11.2023 – 26.05.2024. And possibly also in the accompanying publication, which we haven't read.

9We admittedly haven't, as yet, read all essays in the catalogue, it may be mentioned somewhere we've not found, but we certainly can't find it in the catalogue's alphabetical listing of projects, which is where we would like to have seen it.