It would inarguably, and inexcusably, be little more than employing a lazy, cheap, unwarrantable, stereotype and innuendo to opine that Hamburg is an apposite location for an exhibition exploring and discussing human societies' relationships with water, being as it is a city where the incessant, clinging drizzle is only interrupted by the regular torrential downpours; rather, Hamburg is an apposite location for an exhibition exploring and discussing human societies' relationships with water, as it is a city where the incessant, clinging drizzle is only interrupted by the regular torrential downpours. And because not only the fortunes and stature of the city were built on water, for all in the distant days of the fabled Hanseatic League, and of the pirates who cooperated with the city's Hanseatic era leaders in their desires to assert Hamburg's primacy on the Elbe1, but also Hamburg is physically built on, and for all physically built in, water. Which means that not only the streets and canals and banks - river and financial - of Hamburg offer access to perspectives on and of our relationships with water past and present, but that our relationships with water future will, invariably, be expressed through, and embodied by, Hamburg's future. Or lack thereof.

With Water Pressure. Designing for the Future the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, not only create space for that exploration of and discussion on human societies' relationships with water, but also for reflections on the roles, functions and responsibilities of design, and designers, in context of forming and defining our relationships with water past, present and future.......

Much as the structural coherence of water is dependent on five molecules, four hydrogens and one oxygen, linking together, so the structural coherence of Water Pressure. Designing for the Future is dependent on its five covalent chapters; five chapters which although the spatial realities of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, MKG, mean are arranged linearly can be considered, and should certainly be approached as, a 3-dimensional molecule.

A linear 3-dimensional molecule that one enters via the chapter Water Stories, a collection of stories of a type that, certainly here in Europe, but also, inarguably, globally, used to be a lot more familiar than they are today; stories of our direct, individual, relationships and associations with water be they of the spiritual, religious, folkloric types or the more practical management and physical interaction types. Stories illustrated by, and amongst many other objects and works, Morna Livingston's 2002 book Steps to Water: The Ancient Stepwells of India with its descriptions of a (more or less, can be considered) vernacular water collection and management system of the type that western, European, engineering has tended to deride and deny, without ever attempting to understand and reflect upon; or by numerous examples of religious water holders including a 13th century CE aquamanilia, an object used by Christians for ritual handwashing, a ritual known in (near all) religions, and which, as discussed in context of studio b severin's project Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency as seen at feldfünf, Berlin, has unquestionable, and very informative, psychological connections, as, inarguably, does the bottle for Lourdes water on display in Water Pressure, a Lourdes water bottle that also opens paths to considerations on the commercialisation, and wider misuse, of all religions. Or by Katsushika Hokusai's ca. 1830 woodcut The Great Wave off Kanagawa a work that has rarely looked as menacing and damning as it does in Water Pressure: Are the sailors praying? Or are they asleep? Or are they already dead and awaiting their unavoidable fate? And us all in our flimsy boat of contemporary society?

And an anthology of Water Stories, bound by, framed by, on the one side a timeline of water and human societies in context of ecological, political, cultural, engineering and scientific developments; a timeline starting all those billions of years ago when water based cyanobacteria began the processes of evolution that led to all life on earth, and passing over events and objects and relics such as, for example, the ca 8000 year old Aboriginal depictions of rising sea levels in and around the contemporary Australia; the construction by the Khasi of northern India some 2000 years ago of bridges from woven rubber fig tree roots, bridges that also featured in All Hands On: Basketry at the Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin, and living root bridges which today can withstand the monsoon floods; 6th century BCE examples of Dhunge dhara fountains in Nepal, components of a system of drinking water supply that served, and in context of those still operational, serves, both functional and ritual roles; the development of sewers in 19th century Europe as one of the main contributors, as discussed, for example, by Die Stadt. Between Skyline and Latrine at the smac – Staatliches Museum für Archäologie Chemnitz, to enabling the development of contemporary European cities; the so-called Great Green Wall project instigated in 2005 and that seeks to tackle the increasing desertification across the Sahel region on northern Africa; or the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in south-eastern Ukraine as an example of water as a weapon, a role water/access to water could all too easily regularly take on. Before ending with a noting of the ongoing project to remove four dams by more peaceful methods from the Klamath River in northern California, a project that seeks to redress the environmental, social and cultural problems caused by damming the river.

And a timeline that also ends with mention of the more intense storms climate change will bring with it, the curators noting that one source of these more intense storms is "warmer ocean surface temperatures", and thus tending to underscore the dangerous, fatal, fallacy, as discussed from Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House at the Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein, embodied in General Motor's 1960s belief that "in warmer seas are new realms of pleasure". No General Motors, in warmer seas are the annihilation of life on earth. Yet dangerous, fatal, visions of tech conglomerates we as a species seem doomed to believe in to the bitter end.

Thoughts which also help underscore that following the timeline is to follow an ongoing move away from natural, intrinsic relationships with water towards ever more organised, managed, artificial, relationships, a move from cultural relationships to commercial relationships, a move, if one so will, away from the direct, individual, relationships and associations with water implied in the earliest Water Stories to the detached, impersonal, relationships and associations of so much of contemporary society.

And a timeline bound, framed, on the other side by Marjetica Potrč's mural The Time on the Lachlan River and the visual essay The Rights of a River: the later depicting the, ultimately successful, campaign to protect Slovenia's rivers from commercial exploitation, the former the ongoing campaign of the Wiradjuri of New South Wales, Australia, to prevent expansion of a dam on the Lachlan river which threatens their traditional waters. Two campaigns which find an echo in the timeline through the marking of the granting in 2017 of legal rights as an individual to the Whanganui river in New Zealand, the first act of its kind; and thus three river tales which as a triptych allow for appreciations, as also discussed in, for example, Garden Futures. Designing with Nature at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, not least in context of global campaigns to enshrine rights for the environment in national constitutions and/or for a crime of Ecocide, that amongst ever wider sections of the population, attitudes and opinions are changing, that environmental responsibility is being seen as more than recycling and planting trees, is being appreciated as a way of thinking and acting, and that ways are being sought back to the more natural, intrinsic relationships with not just water but the environment as a whole, if now in context of rigid legal frameworks rather than supple, evolving, tradition.

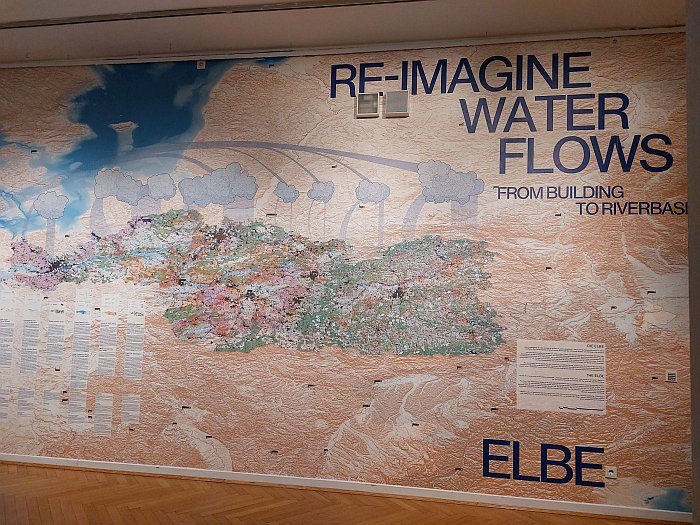

From Water Stories there is no fixed flow through Water Pressure rather you are free to cruise through, over, the other four chapters as you see fit; a boat trip that is also a journey through differing aspects of water and our relationships with water, be that in context of the architecture and urban planning of Thirsty Cities with its reflections and discussions on and of water in context of Copenhagen, Mexico City, Hamburg, London, Lagos and Chennai, the later making note of the project City of 1000 Tanks, a project which, in effect, seeks to re-introduce, re-activate, the ancient, (quassi-vernacular) stepwell principle met in Water Stories as a way of approaching solutions to the myriad water problems of contemporary Chennai and environs, and which as such not only reminds of the problems born of the arrogance, and refusal to look backwards, of our shouty contemporary age, but also reminds, as Hot Cities: Lessons from Arab Architecture at the Vitra Design Museum Gallery could have had it not been pulled early after Der Spiegel got cross, that we in Europe can learn from those outwith Europe, we just have to listen rather than explaining.

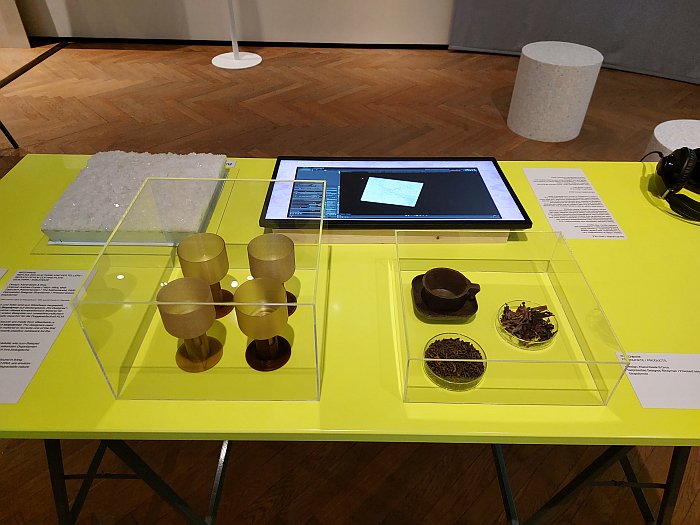

Or in context of Ecosystems, on how human activity impacts on water systems and and how humans can work with water systems, and as discussed via, for example, rising sea levels in context of The Republic of Fiji's published plans for relocation processes for communities impacted by rising water levels, or its neighbour Tuvalu's planned move to the Metaverse when the physical nation is submerged by the Pacific Ocean, relocation plans, that as far as we can ascertain, Hamburg has yet to set out, but would be well advised to consider formulating, and/or begin constructing stepwells; the Weedware project by Zaandam, Netherlands, based studio Klarenbeek & Dros that employs a pressed seagrass biopolymer as a material for production objects of daily use, and which is presented in Water Pressure as a responsible, regenerative, use of the sea as a resource as opposed to the realities of contemporary fishing, dredging and the thoroughly bonkers sea bed mining that, as discussed from Into the Deep. Mines of the Future at the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen, we seem utterly intent on initiating for no other reason than we all need an autonomous vacuum cleaner and two smartphones. Or as exemplified by the Cloudfisher fog collector developed by Munich based Aqualonis and which, as the name implies, collects the water contained in the air, for all that in the morning mists, and makes it available as fresh water thereby increasing access to fresh water, a process that although described in Water Pressure as "new" is another of those ancient water practices that European science and engineering deemed unnecessary and archaic before failing to provide functioning, practicable, alternatives.

Or in context of Bodily Waters, that undeniable fact that life on earth didn't just start in water, but that water is the key to all life on earth, a chapter which concerns itself with not only the waters of the body in terms of the water balance of the human body, but also with the consequences of human activity on water availability for, the water balance of, non-human bodies, with discussions on sanitation, on hygiene, on water as a cleanser of body and soul and also with discussions on the supply of safe, fresh water, that thing that shouldn't be a question but which inexplicably is, while we all busily develop flying cars and AI deepfake software. Or at least those of us (still) with access to clean, fresh drinking water do.

Or in context of Invisible Water specifically the water demands of industry and agriculture and increasingly industrial agriculture, the latter reflected on in Water Pressure through, for example, Jane Wither's Studio's ongoing Wonderwater Café project which details the water footprint - not a contradiction, rather an oxymoron - of foodstuffs on the basis of meals offered at real cafés; through two beers brewed from recycled, greywater, both brewed by firms seeking to promote their water recycling technology through the power of beer, but which also help underscore that a rise in craft brewing isn't necessarily, automatically, a rise in the sustainability of the brewing industry. Or through two photos by Augsburg based photographer Tom Hegen: one from the Lithium Series taken at the Salar de Atacam, Chile, where lithium mining, and its associated water usage and effects on the local water ecosystem is causing environmental and social damage; the other from the Greenhouse Series depicting the mass plastic growing houses in the region around Almeria, Spain, which produce so much of Europe's fruit and veg, but which not only require enormous amounts of water but are destroying the local environment. The latter a work that in the beauty of its brutality is all but guaranteed to make the invisible water of strawberries in Hamburg in March as tangible as those of the fruit in your mouth. And certainly to take the edge of the sweetness.2

A focus on the Invisible Water of industry and agriculture and industrial agriculture that very naturally forces you, certainly forced us with our singular, idiosyncratic view of the world, to focus on furniture. How moist is that interior of yours? Probably more so than you think. Not least because you've never thought about the water content of your furniture and furnishings. We certainly never had. But imagine if you could feel it. Imagine if you could experience the moisture of your furniture first hand through the medium of your body. And, yes, we are open to someone stealing that thought for a graduation project. A moisture that comes not only from the production and distribution and marketing of the objects themselves but also through their development, including those myriad attempts that led nowhere and were abandoned, that unseen resource wastage in all design processes and which, to evoke a Victor Papanek, contributes to making furniture, industrial, designers so harmful.

And also very naturally forces you, and this time it is us all, to question how moist is a museum. How moist is the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg? As we were approaching the museum we passed a lorry delivering those massive plastic vats of water the feed water dispensers/coolers, plastic water vats which may or may not have been for the MKG, we didn't ask, but the MKG doesn't have any actual neighbours on the Hauptbahnhof side where the lorry was parked, so we presume they were for the MKG. But whether they were or weren't the thought that they could have been very neatly highlighted that water and relationships with water isn't just a subject for a museum exhibtion, but is also a subject for a museum institution. A subject, a question, the MKG seek to approach in context of Water Pressure not least through a mural - presumably created with water free inks - by Rotterdam, Netherlands, based, and appropriately monickered, OOZE Architects & Urbanists, which presents both a critique of the (largely) linearity of the museum's current water use and a discussion on possibilities for a more cyclical, and reduced, less invasive, future usage based on an analysis of the museums five water systems: on the supply side, drinking water/sanitation, central heating, fire protection and humidification, the latter arguably an example of invisible water, albeit one hidden in full view in the exhibition galleries, and on the disposal side the rain water that lands, very regularly, on the building's expansive roof and which would seep into the soil were the MKG not there. A non-existence, non-tangibility, as the mural helps elucidate, the MKG is seeking to achieve via a number of measures and adaptations. Criticisms and considerations on alternative possibilities the MKG, through undertaking in context of themselves, very much encourage, admonish, all institutions, and home owners, to undertake and act upon.

A critical self-reflection that is also very much fostered and advanced and demanded in the viewing of Water Pressure.

Much like the rain that has fallen in and on Europe this February feels like a lot of water, but probably wasn't, certainly not in relation to the amount needed, probably was but a minimum, so the volume of texts to read, graphics to study, videos to watch, and objects to engage with in Water Pressure can at first glance leave you feeling, pressured, pressurised, and a little water-logged; however, it is but a light covering of that which is needed. Something that becomes clearer the longer you engage with the five chapters.

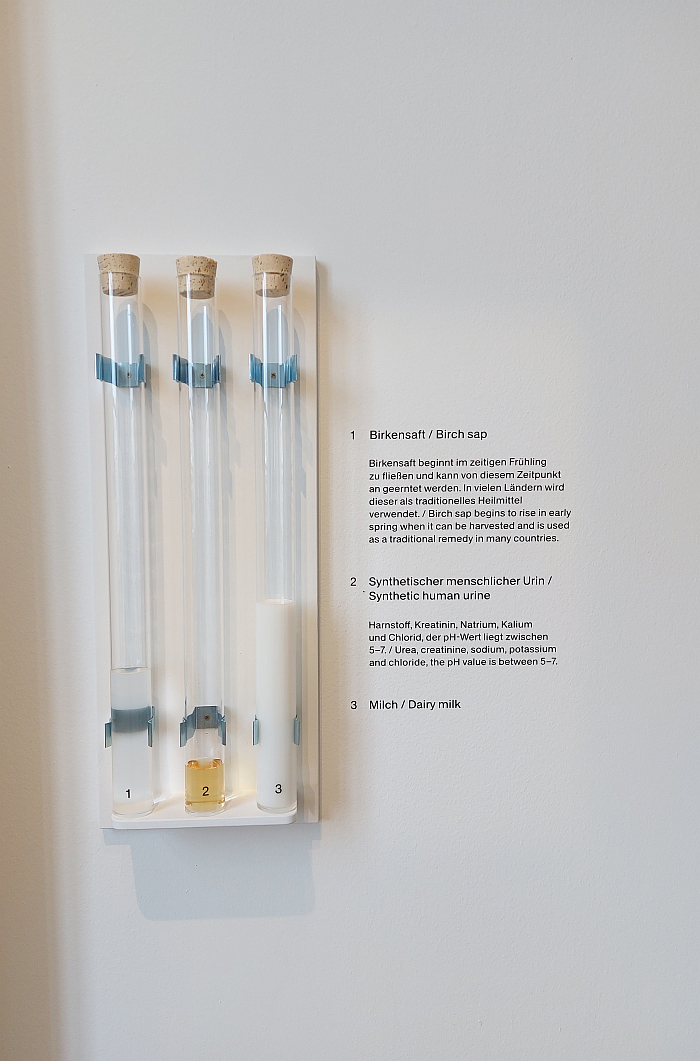

An engagement that is as easy as it is stimulating, not least on account of the satisfyingly broad mix of projects and positions and contexts and genres, all ably supported by concise bi-lingual German/English texts, texts which also define and explain various keywords that all might not be familiar with, something the MKG are keen on doing in their exhibition texts and which is very pleasing; by a reading corner of books that expand on the themes approached; and also by a series of tubes filled with a variety of liquids by way of elucidating that water isn't water but is water, and as such, through forcing you to reconsider water, help you re-formulate questions you thought you'd long since answered. And an engagement also eased by the pleasing manner in which Water Pressure through its discussions and projects and diversity continually, if imperceptibly, not only raises your appreciation of the importance of the themes therein, and also of the inter-connectivity and mutuality of many of those themes, but also raises your appreciation of the importance of getting on with the task of approaching solutions to our contemporary malaises, of getting on with the task of reducing the pressure on our water, and the pressure of water on us.

And thereby Water Pressure exists not only as an admonishment that we need to re-establish, reformulate, our relationships with water, of the need to return to water stories of the type met at the beginning of Water Pressure rather than our contemporary, self-authored, stories of too much water, too little water, too dirty water, but also allows Water Pressure to exist as a sensitisation of the fact that the tools for changing the narrative are there, are being developed and explored, but that ultimately it needs us all to do our bit, makes very clear that in terms of future relationships with water, and by extrapolation the future of life on earth, we all are designers. And that we always were, but that for too long we've ignored our responsibilities. For too long we've allowed the pressure to rise unchecked.

Water Pressure. Designing for the Future is scheduled to run at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Steintorplatz, 20099 Hamburg until Sunday October 13th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.mkg-hamburg.de

1We don't know, we weren't there, but according to Carsten Jahnke, Die Hanse, Reclam Universal-Bibliothek Nr. 19206, 2014, page 179, Hamburg employed pirates to attack ships carrying grain loaded at other Elbe ports by way of seeking to establish Hamburg as the primary grain port on the Elbe. Which is obviously very cheeky. But, according to Jahnke, not an isolated use of pirates to lever commercial advantage: everyone was at it.

2Just to clarify, we didn't have any strawberries, or indeed any fruit, while in Hamburg. Nor can we imagine any one would have any out of season fruit imported from Almeria having seen Tom Hegen's Greenhouse Series.......