Perfectly Imperfect – Flaws, Blemishes and Defects at the Gewerbemuseum, Winterthur

There is a convincing argument to be made that in our contemporary age perfection is one of our primary aims, one of our guiding aims, individually and collectively. A convincing argument to be made that perfection is, to paraphrase a Shane MacGowan, ‘the measure of our dreams’. And there are no shortage of experts out there to tell us all how to achieve that perfection, in all areas of life and work and love and home and hobby.

With Perfectly Imperfect – Flaws, Blemishes and Defects the Gewerbemuseum Winterthur question perfection, and society’s fascination with perfection…….

There is something particularly satisfying about an exploration of perfection, a questioning of perfection, being staged in Switzerland a country universally known for its perfection, universally known for its perfect trains, perfect clocks, perfect cheese, perfect chocolate, perfect cow bells, perfect mountains, perfect perfection.

Thus a fitting context, a ‘perfect’ context, in which to question perceptions of and relationships with ‘perfection’.

Perceptions of and relationships with perfection Perfectly Imperfect – Flaws, Blemishes and Defects confronts in context of five perspectives on perfection and imperfection, five brief if wide-ranging discussions on and of perfection and imperfection, five discussions on our understandings of perfection and imperfection, on the role and function of perfection and imperfection, on the borders between perfection and imperfection.

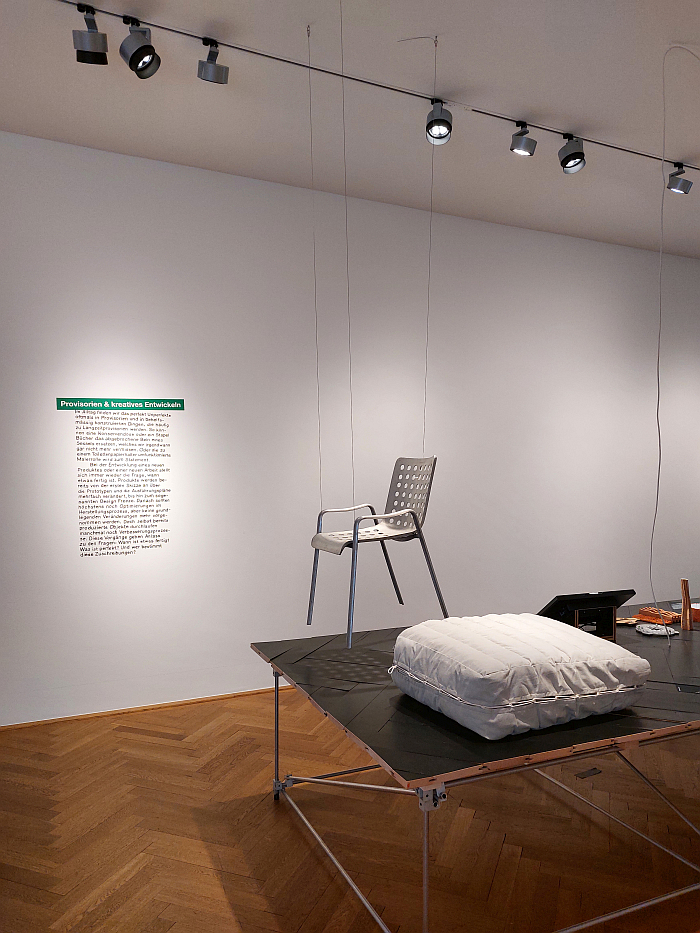

Five confrontations populated by and illustrated via a pleasingly wide range of international objects and projects, speculative and commercial, theoretical and practical, including, and amongst many others, Pieke Bergmans’ 2014 Melted Bronze chair which, à la Stefan Wewerka, has legs that flow far beyond that which conventional statics recommends, but which in contrast to a Wewerka chair can be sat on and used as a functional sitting object, what you see isn’t always what you get; the 2011 video game The Elders Scroll V: Skyrim which in its original version has innumerable programming errors, bugs, which, for example, mean that woolly mammoths suddenly take off and fly away, a fallibility of digital computer technology which obviously bodes well for our coming AI future, ¿how much damage could an AI generated and disseminated AI bug, an AI generated and disseminated flying woolly mammoth, actually cause?; Hans Coray’s Landi Chair from 1938, one of the classics of Swiss furniture design, and a work that, as one learns, has been re-worked and re-designed innumerable times since it premiered at the 1939 Swiss National Exhibition, a.k.a. the Landi, and which as such embodies the question when is something finished? When has something achieved perfection? What value a chair frozen in time on a museum pedestal? A questions in many regards also posed by, and embodied in, Jacob Strobel’s re-design of Horst Heyder’s EW 1192 chair. And also, in many regards, also posed by, and embodied in, the ancient Japanese art of Kintsugi in which a broken porcelain object, that which elsewhere is disposed of, is repaired with gold, more accurately gold and Urushi lacquer, thereby not only accepting damage as part of the object biography, with all the poetry that contains, but also enabling a further development, physically and emotionally, of and with an object considered finished.

And also featuring an introduction to the little known science of Lumomonsterologie i.e. a taxonomy of misformed and misshaped matches developed in the 1980s by (Ost) Berliner Peter Herbert and which in its banality and beauty not only allows for differentiated reflections on mass industrial production as the solution to the supply of our objects of daily use, but also on the hows, why and wherefores of our artificial systems for classifying that which occurs naturally, those human attempts to harness and control nature through squeezing it into a human defined classification table, that Organizing Things as discussed by the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge, Berlin. And which can also be considered a component of optimisation; an optimisation that Lumomonsterologie helps highlight is closely related to perfection. Thereby implying that for all a search for perfection has inarguably been a component of all human societies for centuries, our contemporary European longing for perfection is a component of the world view bequeathed us by the Functionalist Modernists. An implication tending to be supported by W. Heath Robinson’s How to Live in a Flat, his 1936 critique of Functional Modernist architecture and design, in which the Functionalist Modernist Utopia he parodies is one of optimised perfection, perfection via optimisation. If a Utopia in which the problems are all too obvious, and not just those problems impudently authored by Heath Robinson.

Problems of perfection also explored in Perfectly Imperfect.

An introduction to Peter Herbert’s science of Lumomonsterologie as devised and defined by Peter Herbert, as seen at Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

Problems caused on the one hand by that way the human species has of denying that we don’t understand everything, of believing in our infallibility, believing we can actively develop perfection in complex, volatile systems we don’t fully understand, and believing in the perfection of our solutions, our perfect solutions which all too often turn out to be anything but. And as exemplified in Perfectly Imperfect by, and amongst other examples, asbestos that perfect building material, that perfect insulation material, were it not for its extreme toxicity and carcinogenicity; or by urban planning, the curators making particular note of 1970s housing estates, projects which may have perfectly achieved their aim on providing a maximum of affordable accommodation, but which, invariably, in the singularity of the pursuit of that aim forgot the social and cultural necessities of life. And urban planning to which we’d add, being as we are in Switzerland, the innumerable warnings of a Lucius Burckhardt, not least his criticism of what he describes as a liner ZASPAK — Zielsetzung, Analyse des Problems, Synthese, Planung, Ausführung, Kontrolle — urban planning process. [Objective, Analysis of the problem, Synthesis, Planning, Execution, Control: OASPEC].1 And a linearity that, arguably, is also at the root of a Tsuyoshi Tane’s criticism of contemporary construction processes which have bequeathed us an architecture in which “we are diminished by the modern global language. We lost the grammar, we forgot the pronunciation, and many vocabularies have been erased”2, thus implying that while geometry may teach us linearity is perfect, it isn’t always. And loses and forgetfulness through a striving after a perfect, optimised, construction process Tane sought to counter in his Garden House for the Vitra Campus through a “trial and error” approach.

Fixed linearity as opposed to trail and error that can also be considered a component of the problems of perfection highlighted and discussed in Perfectly Imperfect arising through an undervaluing of imperfection, through rejecting imperfection, something explored in Perfectly Imperfect in context of, for example, serendipity as a path to progress as exemplified by the discovery of penicillin, or the development of the teabag, safety glass or the telescope which, one learns, arose from two early 17th century children playing with lenses in spectale-maker Hans Lipperhey’s workshop. And a telescope, a serendipity and an imperfection that remind very much of a Paul Feyerabend’s telling of how Galileo employed an early 17th century telescope to ‘prove’ Copernicus correct3, albeit an early 17th century telescope that would have been, by contemporary standards, low-quality, inaccurate, rubbish, would have offered but an imperfect view of the night sky, would have offered a view as imperfect as that through the large sheet of so-called Crown Glass that stands in Perfectly Imperfect, one of the earliest methods for producing large sheets of glass for windows and which are characterised by their imperfections. Imperfect telescopes that meant Galileo had to guess quite a lot. As did Albert Einstein. Albeit both guessing very well. And a Paul Feyerabend, and arguably also a Lucius Burkhardt, who in general admonish against rejecting that which doesn’t fit in conventional frameworks, admonish against rejecting the imperfect, and admonish for always being open to the unexpected, embracing the possibility of the unexpected.

And telescopes, Galileo’s rubbish telescope, serendipity, trial and error, imperfection, perfection, that can be particularly satisfyingly reflected on in Perfectly Imperfect through on the one hand the slide show of photos by Sandra Danicke of examples of Gambiarra, that Brazilian concept of developing makeshift solutions with that which is at hand, as exemplified by, for example, using a broom to keep an oven door shut, or a wine bottle cork as a pot lid handle, or a shampoo bottle to prevent a window shutter from being completely closed, or by innumerable examples in your home and workplace. And on the other via Marjan van Aubel and James Shaw’s Well Proven Chair from 2012, an object crafted from a novel material discovered by chance after the pair mixed wood chippings and a natural resin. And also reflected on in the objects of the Simultanea collection by Munich based goldsmith Peter Bauhuis in which a mix of molten metals are poured into a mould and left to react and interact with one another as they see fit, thereby producing a never repeatable serial product. And a Simultanea collection which also reminds of Nürnberg based glassmaker Cornelius Réer’s steel mould works with their cold wrinkles, seams and asymmetry, and of which Cornelius notes “what I’m showing today are actually mistakes“, albeit endlessly charming, engaging and communicative “mistakes”. Mistakes, as with those of Simultanea, that bring us further in our understandings and appreciations than any number of contemporary ‘perfect’ glass or metal objects could.

Simultanea by Peter Bauhuis, Well Proven Chair by Marjan van Aubel and James Shaw and an anonymous Morocco carpet, as seen at Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

And a serendipity, and planned imperfection, also approached in, accessible through, Perfectly Imperfect in context of those concepts and projects which strive for imperfection by way of achieving a perceived perfection, which seek a perceived perfect imperfection, including Shabby Chic and other attempts to prematurely age objects of daily use, and which in its diametric juxtaposition to the Gebrauchspatina, the Patina of Use, of a Karl Clauss Dietel underscores not only the abhorrent dishonesty of Shabby Chic, and associated nonsenses, but also how in our contemporary age the links between us and our objects of daily use are being ignored, negated, sacrificed in the name of fashion, t****, and a ‘perfect’ social media profile. With all the inevitable problems that brings with it. And a dishonesty, and problems, also inherent, as Perfectly Imperfect reminds us all, in our stonewashed, bleached and similarly ‘old before their time’ jeans, a fashion, a t****, in whose name the majority of European consumers never think to question the ecological and social and political and economic damage done. Only concerned as we are that the look good on us. What’s perfect for you may not be perfect for others. See also the so-called super foods.

Thoughts which allow one to approach a better appreciation that for all that, as noted above, questions of perfection and imperfection aren’t new, are arguably one one of the oldest of human debates, they are increasingly becoming relevant in contexts outwith the purely theoretical discourses on aesthetics and beauty that they have occupied for centuries and are increasingly becoming tangible components of our global social and environmental problems, tangible components of the damage to our global social fabric, and thus problems in themselves. Something also underscored by, for example, the reflections enabled by Alexander von Dombois’ Beetlechair project as seen at Passagen Interior Design Week Cologne 2024 on the accepted criteria for wood in and for furniture, criteria for ‘perfect’ wood that excludes ‘imperfect’ spruce stained blue by Ophiostoma fungus, although it is structurally sound. Similarly the carrots in Uli Westphal’s Field Study I project presented in Perfectly Imperfect, carrots excluded from the commercial European human food supply system for not being physically ‘perfect’ although still being ‘perfectly’ edible. How can we ever hope to feed a growing world population if we reject carrots on account of their form, reject them for not being a ‘perfect’ expression of a carrot? What is a ‘carrot’ anyway? And what role does the taste play in that ‘perfection’. Is Carotomonsterologie more ore less absurd than Lumomonsterologie? But we practice it?

Thereby allowing Perfectly Imperfect to underscore that it is becoming increasingly important, increasingly urgent, that we critically question not only what we understand as ‘perfect’ or ‘imperfect’, but why? Why we make that differentiation? How do we make that differentiation? Who decides on the rules of that differentiation? And what if we didn’t?

Perfectly Imperfect is a good place to start that critical questioning.

As is Switzerland.

Melted Bronze chair by Pieke Bergmans (l), Smoke Thonet chair by Maarten Baas (r) and on the wall Stephanie Harke’s Bettschuhe project, as seen at Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

Switzerland isn’t perfect.

The trains aren’t perfect, for a start Swiss trains have no internet. Which is ridiculous. If you want internet on a train in Switzerland make sure you’re in a German or French or Italian one. Their clocks aren’t perfect, they may work as planned but are components of an imperfect system, components of an attempt to squeeze something natural into a human classification system, a human approximation, something tending to be underscored by a Tõnu Riit’s crticism of the round watch/clock face so beloved of the Swiss as, “sisu ja vormi mittevastavusest”4, a ‘mismatch of content and form’. Their cheese is good, but more ‘perfect’ than cheese from elsewhere? Their chocolate is good, but more ‘perfect’ than chocolate from elsewhere? Their cow bells are good, occasionally very good, but more ‘perfect’ than cow bells from elsewhere? And if their mountains are perfect, will they become ‘imperfect’ when climate change increasingly causes bits to fall off? Causes the glaciers to retreat ever further. What then? Did Hans Coray’s Landi Chair become ‘imperfect’ when people started altering it? Is Hans Coray’s aluminium Landi chair more or less ‘perfect’ Swiss than the wooden vernacular architecture of the 1939 Swiss National Exhibition, Landi, that, as Luicius Burckhardt, notes, has “had an incredible, partly good, partly dubious, influence on Swiss architecture. Even today, everything in our architecture that has a national character and which strikes foreigners as Swiss is in some sense á la Landi”.5 A wooden vernacular ‘perfect’ Swiss architecture preserved for all time in the Ballenberg open air museum, albeit without all the social, economic, health, hygiene, legal et al problems and challenges of yore, problems and challenges which meant that, as Rolf Fehelbaum reminds us, “life was hard and it would be an injustice to romanticize it”.6 But which we do nonetheless. Romanticize it as ‘perfect’. Romantacize away the flaws, blemishes and defects. The imperfections.

Switzerland isn’t perfect. Never was. Never will be.

And that is good so. Not least because as Perfectly Imperfect through its confrontation with perceptions of and relationships with perfection, and its celebration of the joy, the value, the necessity of the imperfect, allows one to better appreciate, not only is perfection limiting and restrictive, and not an actual thing but something we’ve artificially devised and developed and internalised by way of making life more complicated than it need be, but we require the imperfect to allow us and our societies and cultures to evolve and develop. Always have. Always will.

Accepting that, learning to embrace the imperfections and serendipitous rather than undertaking a blinkered chasing of a pre-defined perceived perfection, and learning to dream of flaws, blemishes and defects as our measure of all things, might just be important going forward, in enabling us to go forward.

Perfectly Imperfect – Flaws, Blemishes and Defects is scheduled to run at the Gewerbemuseum, Kirchplatz 14, 8400 Winterthur until Sunday May 12th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.gewerbemuseum.ch

An invitation to make your own ‘perfect’ chair, part of the experience of Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

Chesa Chair by Jörg Boner and the project Pressed Motion by Martina Häusermann, as seen at Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

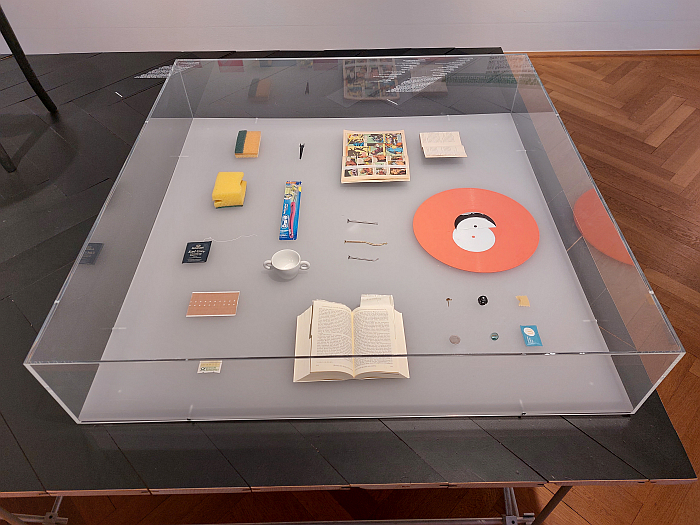

Industrially produced objects with an array of errors, as seen at Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

A Landi Chair by Hans Coray and recycled mattress from the Matalàs project by Noémie Soriano, as seen at Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

Field Study I by Uli Westphal (l) and an example of Crown Glass, as seen at Perfectly Imperfect. Flaws Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur

1. see Lucius Burckhardt, Die Kurzsichtigen und die Weitsichtigen, in Markus Ritter and Martin Schmitz [Eds.], Lucius Burckhardt. Der kleinstmögliche Eingriff, Martin Schmitz Verlag, Berlin, 2013, page 22ff

2. Tsuyoshi Tane, quoted in the exhibition Tsuyoshi Tane: The Garden House, Vitra Design Museum Gallery, Weil am Rhein

3. see Paul Feyerabend, Against Method, Fourth Edition, Verso, 2010, primarily Parts 8 – 14

4. Tõnu Riit, Aeg ja Kellad, Kunst ja Kodu, Nr. 1, 1975, pages 3-7

5.Lucius Burckhardt, achtung: die schweiz – Der Urtext, reprinted in Markus Ritter & Martin Scmitz [Eds] achtung: die Schweiz. Der Urtext von Luicius Burkhardt über die idee einer neue Stadt, Martin Schmitz Verlag, Berlin, 2019

6. Rolf Fehlbaum, Ballenberg? in Rolf Fehlbaum [Ed.] A Way of Life. Notes on Ballenberg, Lars Müller Publishers, Zürich, 2023

Tagged with: Blemishes and Defects, Gewerbemuseum Winterthur, Perfectly Imperfect, Perfectly Imperfect – Flaws, Winterthur