Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s at the Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn

In the popular narrative of architecture and design in the second half of the 20th century the phrase ‘Postmodern’ is widely used; a wide use, and an equally wide, unquestioning, popular acceptance of what is meant, that all too often not only blinds us all to the heterogeneity of the period but also impedes meaningful debate and discussion on the motivations, positions and realities of that period. And on the lessons of the period.

With Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s the Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn, remind of the need for more nuanced, and wider-ranging, reflections and discussions…….

Based on a Masters Thesis that has become Doctorate research by Triin Reidla at the Estonian Academy of Arts, Tallinn, a Masters Thesis whose ever glorious title Such an Ugly House! Postmodern Residential Buildings and Issues of Evaluation1 encapsulates not only so much of the debate in recent years of architecture and design in the the 1970s and 1980s, but also so many of the problems of prejudice and preconception that colour so many discussions on the period, brings a emptiness to such discussions that often makes them meaningless, leads, as noted from Everything at Once: Postmodernity, 1967–1992 at the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn to a collective ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ as response to the period, Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s is based around six short thematic chapters, opening with Kontekst, The Context, which is always an excellent place to start, but one far too few discussions and dialogues choose to start from.

An opening chapter which explains that the first private houses in Estonia expressive of novel positions originating in the middle of the second half of the 20th century… no, we’re still not using the phrase ‘Postmodern’ ourselves, and, yes, are still looking for appropriate alternatives… the first private houses in Estonia expressive of novel positions originating in the middle of the second half of the 20th century were realised in the late 1970s, works such as, for example, the two Villa Valeri’s developed by Leonhard Lapini in Laagri to the south of Tallinn in 1976 & 1977, or the so-called Venna maja, Brother’s House realised by Veljo Kaasik in Merivälja to the north of the Estonian capital in 1975, a work that in its construction based on a monolithic brick and concrete core cloaked in a wooden facade not only does that ‘hiding your workings’ thing of the late 19th/early 20th century that so annoyed the Modernists, but also tends to echo the late 19th/early 20th century wooden houses of the Pelgulinn district of Tallinn, and the early 20th century wooden houses in it’s immediate vicinity in Merivälja; however, for all that in doing such it unquestionably, and unnervingly, awakens the spectre of the Historicism Modernism had sought to expel, it does so in a manner that no one would, could, conceive to accuse of being in any regard backward looking. Thereby opening important reflections on the ‘Post’ of ‘Postmodern’.

And an opening chapter which also helps elucidate, amongst other aspects, the urban planning framework(s) within which private houses of the type under consideration were realised, introduces some of the mundane practical factors associated with construction in the period under consideration including material supply, and also discusses the motivations amongst the varied and various architects involved, not least motivations for a move away from the quadratic rationality of the inter and immediate post-War Functionalist Modernists and a desire for more art in architecture, the latter, in many regards, a re-igniting of that so central late 19th/early 20th century discourse on architecture, functionality, art, expression, on the role, job, of the architect and architecture. A discourse that our fledgling 3D printing and AI will invariably also re-ignite, and increasingly influence and inform. But where will they, it, take us? How will we employ the new technology? And will we try to learn from the lessons of the past as we attempt to understand the possibilities of the future? Or do we know all the answers, just need the technology to work?

From its opening discussions Bold and Beautiful moves on to explore Construction and Architecture, two chapters whose spatial closeness helps focus attention on the question of the relationship between the two, and how that relationship has changed over the centuries of human society; The Dynamic Layouts of Private Houses a chapter essentially concerned with interior architecture and which helps elucidate that often such was determined as much by the need for a creative circumnavigation of the, then, prevailing Soviet planning rules as by considerations on spatial use, for all circumnavigating the regulations concerning the percentage of the interior that was to be devoted to ‘elu ja -abiruumid’,’living and utility rooms’ often requiring, as one learns, a very creative solution. A forming of space to comply with building regulations that is an example ‘form follows function’, if ‘function’ is understood as staying one step ahead of the authorities, and thus a reminder that ‘function’ isn’t always a purely physical, tactile, concept, and of the problems of designing based on an unreflective application of the correspondence. And a necessity of creatively circumnavigating local planning regulations to achieve aims that is an integral part of contemporary global construction and architecture, and which shouldn’t be confused with the nefarious, illegal, deadly, circumnavigating of gangsters.

In addition The Dynamic Layouts of Private Houses allows access to appreciations, confirms, that for all the playfulness and impertinence of the exteriors of the presented works, rational quadratics and Functionalist relationships were often employed in the interiors, thus allowing for a further confirmation that for all we like to pigeon-hole architecture and design such is only helpful in coffee table book and commercial contexts, not in context of helping us appreciate the paths thus taken. And also allowing one to understand the apparent permanence of the primacy of the quadrat in architecture and design and by extrapolation its primacy in European culture and society, a primacy whose vanquishing was a motivation of the period under consideration, a vanquishing which, and as opined from Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński at the Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław, (hi)story would tend to imply is the path we’re on, but whose end we never reach, always seems to be in a distant future. And therefore to enable one to question why that primacy seems so unassailable, why we don’t, can’t, wont, employ spatial use forms more in tune with the irrational irregularities of life. Whose life is linear and quadratic?

And Kohandamine, Modification, a chapter which explores its title in terms of ‘Architecture’ and ‘Usage’ primarily in context of the 1980s and 1990s, those most volatile of global decades and which not only saw many Estonian home builders forced to rethink their plans, but also saw many Estonian house owners suddenly in possession of buildings that no longer fitted their needs, their budgets, their realities, the size of their families, and which, and returning to the opening chapter, helps underscore that Kontekst is always important, and it is rarely static. Thus the need to accept and plan for change, without attempting to predict what that change will be. Because you can’t. You can just be certain it will come and be as ready as you can.

Sketches of Vilen Künnapu’s house for Tõnu Virve (l) and Ain Padrik’s so-called Physicist House (r), as seen at Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn

In addition to unfolding its narrative over six chapters Bold and Beautiful explore its themes, primarily (not exclusively), in context of four locations: Rehe Street in Vijandi, central Estonia, a street/suburb that is a mix of ‘reserved’ and much more ‘bold’ houses that was realised, at the specific behest of the planning authorities in Vijandi, with the intention that “vormide varieerumine peaks olema analoogselt looduses esineva seaduspäraga – metsas ei leia ühtki täpselt sarnast puud, kuid koos moodustavad nad visuaalse terviku”2, “the variation of forms should be analogous to the laws in nature – you won’t find a single exactly similar tree in the forest, but together they form a visual whole”, which is an astonishingly progressive, and poetic, approach for any planning authority, any where at any time, to take; the so-called Arhitekti district of Tartu, an area which, in contrast to the other areas under consideration, each house, more or less, was designed by a different architect3 and which one very much gets the impression was approached more as a building exhibition than as an act of housing provision, something comparable with, for example, the 1930s Modernist Napraforgó street in Budapest; the community of Ihaste on the south-western edge of Tartu whose (hi)story helps elucidate much of the Kontekst and also the Kohandamine, Modification, during the 1980s; and Ilmandu village on the eastern edge of Tallinn, which is predominantly a product of the 1990s and so outwith the period of the title of the exhibtion but very much in context of that period, and thus quite aside from being an interesting and informative community in context of approaching better appreciations of the (hi)story of architecture in Estonia, is also a further reminder of the borderless continuity in the development of architecture and design positions and expressions, a reminder that epochs only exist as an act of ex post facto pigeon-holing. And that we all should look at the specifics in their Kontekst rather than narrowing down to context-free catch-all phrases.

Locations, discussion points, and house projects, that unite to allow a narrative that throughout its course not only helps one approach more probable appreciations of the realities in Estonia in the period under consideration, and the hopes and aspirations and challenges and positions of that period, nor only allows one to begin to approach the question of the characteristics of the Estonian dialect of what is popularly referred to as ‘Postmodernism’, the questions of an Estonian ‘Postmodern’ vocabulary and grammar, but also allows for an easy, natural, pleasing, introduction to many of the architects of the period including, and amongst many others, Valdur Napp, Ike Volkov, Vilen Künnapu, Maire Annus or Ado and Niina Eigi, the latter being the only architects to be commissioned for more than one building in Tartu’s Arhitekti district, and whose works can also be found in Uneversum: Rhythms and Spaces at the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, Tallinn, including Niina’s bunk beds for the pair’s joint Trall Kindergarten project in Pärnu, bunks which despite their rejection of the Functionalist definition of the form function correspondence, are very much a cube. Thus a nice reminder of how difficult getting away from the quadratic is. While the recent demolition of the Trall Kindergarten highlighting the precarious existence of many of the works of the period. And enables a questioning of why that precarious existence?

And a narrative which ends with the chapter Vastamata küsimused, Unanswered Questions, which, and much as opening with Kontekst is always an excellent place to start any discourse and discussion, is always an excellent place to end, one rarely coming through a discourse or discussion directly to a solution. And if you end with questions, you always have somewhere to go.

Bold and Beautiful very satisfyingly leaving you with an embarrassment of directions in which to continue your journey.

Models of houses by Ado Eigi, as seen at Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn

Essentially a bilingual Estonian/English poster showcase backed up by models, sketches and a variety of literature discussing the period, literature, yes, in Estonian, but it is a showcase in Estonia and about Estonia and Estonians, Bold and Beautiful provides for a succinct, easily comprehensible and stimulating introduction to the architecture of the period, an introduction through projects realised and unrealised; an introduction that helps broadens perspectives on the architecture of the 1980s and 90s, helps move one’s gaze from the western European and USA focus that normally dominates and in doing so forces you to question that which you currently understand about architecture in the second half of the 20th century, both as positions and a period; an introduction that is an introduction. A start. A work in progress. As noted above Bold and Beautiful is based on a PhD project and as such one can expect more to come, more insights, more associations, more Kontekst, before it is finished. Or perhaps more accurately before it reaches the next staging post on its journey. As with many of the buildings featured one very much gets the impression it is an ongoing undertaken with no conceivable final destination. With all the benefits that brings.

An introduction Bold and Beautiful also very cordially invites one to extend oneself through visiting the works presented in situ, to continuing your journey of research and discovery in situ; something we intended to do in context of those works in and near Tallinn, but which pressures of time meant we didn’t. But which we will do. As we will visit Tartu and Vijandi. Bold and Beautiful being as it is also an invitation for an alternative tour through Estonia, to view Estonia through your own guide book, one that includes the the progressive urban planners Forest of Vijandi as we are now referring to the Rehe Street suburb, and not via the tourist gaze of conventional guide books, Instagram, TikTok and the Estonian tourist authorities.

Similarly Bold and Beautiful also invites one to extend it through reflecting on that discussed upstairs downstairs in context of the (hi)story of Estonian architecture as presented in the Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum’s permanent exhibition space; a history presented as a timeline from 1900 to today, presented in context of phrases such as, for example, Fantasy, Society, Home, or Culture and presented via projects such as, and amongst many others, the so-called Tallinn House by Karl Tarvas from 1929, Henno Sepmann’s 1957 design for the Song Festival Stage in Tallinn, Arhitekt Must’s Mängu maja, House of Play, kindergarten concept from 2014, or Villa Temmekann in Tartu by Alvar Aalto, the latter a nice reminder of not only the international nature of most cultural developments, that a ‘national’ culture rarely is, is at most a local dialect of an international language, but also of the (hi)storic ties between Finland and Estonia, as does the 1913 Estonia Theatre, Tallinn, by Armas Lindgren and Wivi Lönn.

And a permanent exhibition space that also features a model of and short discussion on the 1979 Lembitu Fashion House project, conceived for, but never realised in, Tallinn by the aforementioned Vilen Künnapu together with Ain Padrik. A work very much reflective of the positions of the period of its genesis, as, inarguably are the works of Karl Tarvas, Henno Sepmann, Arhitekt Must or Alvar Aalto; and a Lembitu Fashion House which stands in the Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum with such an ease and self-confidence, an assurance in its place on the timeline of architecture in Estonia, it’s hard to imagine what all the fuss concerning 1980s architecture is and was about.

Why the calls of “Nii kole maja!”, “Such an Ugly House!”, in Estonia, and elsewhere, everywhere in context of architecture realised between the late 1960s and early 1990s?

The kindergarten project Mängu maja by Arhitekt Must, but is it Modern? Postmodern? Postpostmodern? Or just very engaging? As seen in the Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn, permanent collection exhibition.

An introduction which also very naturally enables and stimulates thoughts on the ‘Modern’ in Estonia that came before the Postmodern’, for all that ‘Modern’ which arose in the 1920s and 1930s when Estonia was enjoying its first flush as a newly independent republic, and which, and much as the equally newly independent Czechoslovakia embraced and explored its new freedoms as discussed in Hej rup! The Czech Avant-Garde at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, is a very fertile Kontekst for novel ideals and avant-garde positions. But how much of that spirit passed into post-War, Soviet era, Estonian architecture and design? What was the architects and designers of the 1980s relationship with it? Can it still be found? Should it still be found? Such questions being some of those directions Bold and Beautiful has sent us off in.

And an introduction whose use of private houses as a conduit is not only particularly rare in architecture, architectural (hi)story, discourses that tend to focus on the, as Bernard Rudofsky so gloriously phrased it, “houses of true and false gods, of merchant princes and princes of the blood”4 and/or on unrealised visions and concepts rather than actual works for actual people, but is also particularly satisfying, not least because being as they are and were by and for private individuals they are not only removed from the direct influence and ideologies of state and commerce, and the influence of state and commerce’s understandings of representative, if, (in)arguably under the influence of private ego understandings of representative, another Vastamata küsimus, Unanswered Question, but also reflect more personal demands, are reflective of more personal needs, reflect opinion in Estonian society of that period. Not the whole of Estonian society, obviously, as a presentation Bold and Beautiful represents only a very small number of the houses realised in the period under consideration and the positions and demands of a small percentage of those who designed and built in the years under consideration, but then so are the palaces, country estate houses and cathedrals architecture (hi)story focuses on, but do represent a window on a part of Estonian society, inarguably one only rarely seen. And a window that is important, as is the contrast to that which the state was undertaking in the 1980s. An important contrast Bold and Beautiful doesn’t directy refer to, but is very much present and which must be a component of any subsequent tour through and to the sites in question.

Equally important is the switch in the title from the “Nii kole maja!” “Such an Ugly House!” of the original 2019 Masters Thesis to “Vaprad ja ilusad”, “Bold and Beautiful”; on the one hand a switch, an important switch, from that off-hand, flippant, manner in which the period is so often approached to one that strives to approach it more positively, if arguably going a touch too far, “Vaprad ja ilusad?“, “Bold and Beautiful?” being, in our opinion, the more objective and probing title, and very much the manner in which we approached the exhibition and will approach Estonia in the future; but which through being positive, through focussing on the positive challenges one to contradict it, something that is always possible but requires active thought, rather than focussing on the negative, which is always easy to agree with, unthinkingly so. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ That thing we all know from contemporary political discourse and the populists fascination with putting down their opponents rather than arguing for their own positions. And thus a change of title that is in itself reflective of the change of perspective we all need to undertake. A change of perspective Bold and Beautiful leads.

And on the other hand a switch from “Nii kole maja!” to “Vaprad ja ilusad”, an important switch, a switch from language we’d all to use to one many of us would at first find odd, which, and as with all changes in language that allow us all to fully appreciate the errors of popular conventions and blithely accepted norms, to fully appreciate how the language we use colours and prejudices our views and view on the world, to fully appreciate that change of language ≡ change of perspective, which allows one to appreciate that only slowly are we acquiring the sufficient distance, are sufficient generation changes occurring, to allow us to approach the period under consideration with the openness and objectivity demanded; to appreciate that, and as discussed from Anything Goes? Berlin Architecture in the 1980s at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, only now are we approaching a position where we can approach the architecture of the 1970s and 80s in a more open, inquisitive, questioning manner.

And in doing so, and in being such, helps highlights the necessity for that more open, inquisitive, questioning manner, and allows one to approach an answer to one of Bold and Beautiful‘s Vastamata küsimused, Unanswered Questions: “When will people be ready to recognise these private houses as significant landmarks in architectural history?”

Viewing Bold and Beautiful allows one to appreciate that the answer is, could be, should be: now.

Or as Triin Reidla very poetically phrases it in her Masters thesis “Selle ajastu pärandi mõtestamine ja väärtustamine terendab ukse ees”5, ‘Understanding and valuing the heritage of this era is waiting at the door’. We just need to open that door, invite it in, listen to what it has to say, question it, engage with it. Who knows what we could learn if we stopped ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ And stopped denigrating it. Stopped patronising it. Stop wishing it wasn’t there. Which yes, is also a metaphor…….

Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s is scheduled to run at the Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Ahtri 2, Tallinn 10151, until Sunday April 28th.

Full details can be found at www.arhitektuurimuuseum.ee

Photos and layouts of works by Vilmar Lill (l) and Ike Volkov (r) for the Arhitekti district, Tartu, as seen at Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn

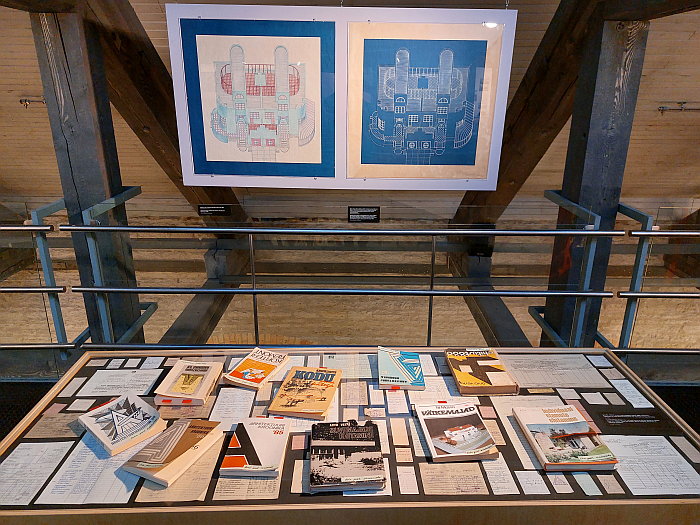

Books on 1980s Estonian architecture and project sketches by Ado & Niina Eigi, as seen at Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn

A view through the quadrant window of Estonian architecture, as can be enjoyed at Bold and Beautiful. Estonian private houses from the 1980s, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, Tallinn

1. Triin Reidla, Nii kole maja! Postmodernistlikud elamud ja nende väärtustamisproblemaatika, Masters Thesis, Eesti Kunstiakadeemia, Tallinn, 2019 Available via https://digiteek.artun.ee/fotod/loputood/magister/event_id-217 (accessed 01.03.2024)

2. Viljandi City Archive, Viljandi linna individuaalkvartalite nr 90 ja 91 tihendamise hoonestuskava, quoted in FN 1 page 44

4. Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture Without Architects. A short introduction to non-pedigreed architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1964

Tagged with: Arhitekti district, Bold and Beautiful, Eesti Arhitektuurimuuseum, estonia, Estonian Museum of Architecture, Estonian private houses from the 1980s, Ilmandu, Merivälja, Tallinn, Tartu, Vijandi