...

... Wilhelm Gutmann used the occasion of Grassimesse Leipzig 1920 to present......

.......we no know.

Or more accurately, in terms of Wilhelm Gutmann generally we no know hardly nothing. Certainly we no know an awful lot more than the we no know about the other Grassimesse 1920 designers featured thus far in these dispatches.

Despite the fact that, arguably, there should be a lot to know.

Born in Frankfurt on April 24th 1877, Happy Birthday!!!, Wilhelm Gutmann studied at the Städelschule, Frankfurt, that so important and influential Frankfurt school of art... from when he studied, till when, what, under whom, with whom, etc, etc, etc is less certain.

All that can be said with a degree of certainty, or at least all that we can say with a degree of certainty, the information will be out there somewhere, is that after his time at the Städelschule he appears to have remained in his native Frankfurt, a city whose daily life was, as best as we can ascertain, one of his primary motifs and inspirations; and that he appears to have travelled regularly to Holland, and to have painted, be that in Frankfurt or Holland, in an impressionist manner that, arguably, was greatly influenced by his regular trips to Holland.

Before he, possibly, switched to a more Cubist approach: in 1929 Adolf Dessler makes note of a still-life "with the Picasso motif of the tobacco pipe, the candlestick and the tobacco pouch" by "a Frankfurter, Wilhelm Gutmann", that was presented at the Ausstellung der jungen Künstler in the Modernen Galerie A. Wertheim, Berlin; and a "Picasso motif" of which Dessler opined, somewhat disparagingly, was "still miss-proportioned, still colourful, with red and green screaming out of the composition, but certainly not untalented"1 Whereby we'd opine that at that time Gutmann would have been 41. Which is quite old for a 'jungen' artist. Or was the "jungen" of the exhibition title more related to the artistic style than the age of the artist? Could there have been two Wilhelm Gutmanns from Frankfurt? But an implication through Dessler that Gutmann had talent, but had studied Picasso a little too closely, that finds an echo in the report from an exhibition in Frankfurt in 1921 of works by Gutmann and Dietz Edzard of which the reviewer notes that Gutmann "is not untalented as a painter", but "thoroughly unoriginal".2 The nature of his art in 1921 is sadly not noted.

The other thing of which we can be fairly certain is that, at some point, but definitely before 1920, Wilhelm Gutmann turned his attention, his creative leanings, to interior design and furniture, if, once again, the whats, whys, wherefores, whos, etc, etc, etc are lost in the mists of time.

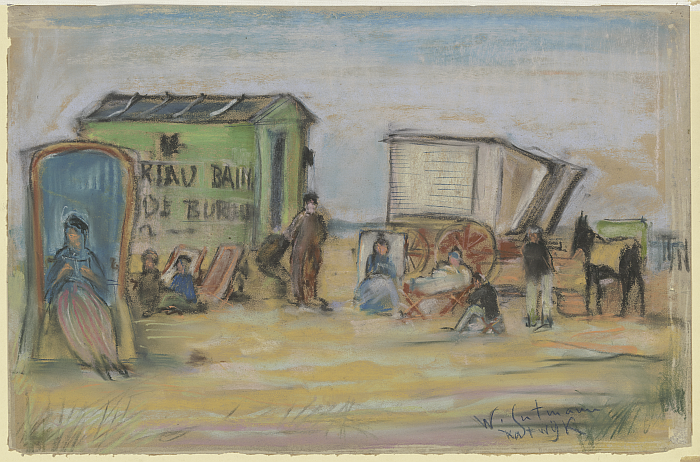

All we (currently) have is sketches of a number of interiors published in the trade press in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Sketches of interiors we can only link to: much as we adore and will be eternally grateful to the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg for their efforts in making historic newspapers and magazines available online for all, their copyright regulations are ridiculous and urgently need to be reviewed and re-imagined. Hence the use of a 1908 painting above, the Städel Museum are a lot more forthcoming.

Sketches of interiors by Gutmann that are fascinating not only on account of their colour — both the fact that they are in colour and thereby remind us that inter-War interiors were very much in colour, something that is all to easily forgotten in the black and white in which they are normally viewed, and also on account of Gutmann's use of colour, supported by Gutmann's sketching technique, which bequeath the spaces he sketches a vitality and animation that one rarely sees in interior design sketches. And which is just joyous to experience. In many regards both in terms of artistic style and the impression awoken Gutmann's sketches remind of a Carl Larsson's sketches of daily life, domestic life, at Lilla Hyttnäs, albeit spaces that are more rational, structured, reduced, if every bit as spontaneous and playful and inviting and functional as those of Lilla Hyttnäs.

Sketches of late 1920s and early 1930s spaces that as Hugo Lang opined in 1927 reflect ideals of comfort as a technical aspect and comfort as "an atmosphere in which you feel at ease, relaxed, happy", comfort as a physical and as a sensuous experience. And of which he also notes, "Boredom cannot arise in such rooms".3 See also Lilla Hyttnäs.

And late 1920s and early 1930s spaces that confuse. Don't appear to be from the late 1920s and/or early 1930s.

1920s architecture and design in Frankfurt is popularly dominated by the Neues Frankfurt project with its myriad Functionalist Modernist housing estates. But Gutmann's interiors for all their rational, structured, reduction have nothing of the more dogmatic Functionalism of Neues Frankfurt. Yet may be, at least partly, based in Neues Frankfurt; certainly there is a sketch from 1927 for a living room for an apartment on a housing estate, a very Neues Frankfurt thing, and where the window with its mix of small and large panes of glass is very much of the type one could, would, expect to find in Neues Frankfurt estate, arguably primarily through Mart Stam, though not exclusively. But not the interior design and furniture. Yes, one can, at times, see, occasional, similarities with aspects of the furniture of a Ferdinand Kramer, for all in the acute angle of many of the chair backrests, although that may also just be peculiarity of the artistic approach. Or may be intended. But even given the similarity of the backrests, and the use of wicker work, there is still a long, long, way to go from from Kramer to Gutmann, and an even further way to go from Neues Frankfurt to Gutmann's Frankfurt.

As there is a long, long way to go from Gutmann to that other important, defining, 1920s interior and furniture design association: Art Déco. While, for example, the sofa next to a staircase in a hallway from 1927 and the, one believes, related, 1927 reception room sofa, positively ooze Art Déco, they are very rare moments in the Gutmann oeuvre. Or at least those bits of the Gutmann oeuvre we're familiar with. For we suspect that is a lot we are unfamiliar with. And as with all those bits of the oeuvre we're familiar with the Art Déco sofas presented in the magazines are done so without context: are, were, they commissions or simply a thinking aloud on Gutmann's part? That would be important to know before using them as guides to Gutmann and his positions.

As it is all we have are contextless sketches. Sketches of late 1920s and early 1930s spaces that don't appear to be from late 1920s and/or early 1930s, but are certainly very aware of the late 1920s/early 1930s.

Or put another way.

The bountiful, uninhibited, use of loose cushions and textiles, a permanent, and one could argue signature, aspect of Gutmann's interiors, on the one hand harks back to the 19th century, for all the regular appearance of tubular bolster cushions, but also predicts the softer, more humane, Modernism of an Aino Aalto or a Charles and Ray Eames, that spontaneity and playfulness of Lilla Hyttnäs as a softening edge to the harshness of Functionalist Modernist positions, that appreciation of comfort as a physical and as a sensuous experience. But could also be loose cushions and textiles from the 1970s. Or from tomorrow.

Similarly Gutmann's expansive, flat, inviting sofas, sofas that in many regards, one could argue, represent a reinterpretation and reimagining, a further development, of his use of loose cushions, something wondrously implied by the 1928 sofa for a living room which appears to be simply cushions on a pedestal, a solution that reminds of a Børge Mogensen's late 1950s daybed concept, but could also be from the 1970s, or the 1980s. Or tomorrow. And 'large cushions on a pedestal' by way of a sofa that is often presented as a construction with discreet metal feet, see for example, the sofa in his living room in a country house from 1933 or the 1932 sofa for a window corner in a living room; metal feet that imply Gutmann was well aware of the machine age that Frankfurt was entering in the early 1930s, but wasn't prepared to give the machines all the say; he's moved on from the rattan pedestal of the sofa in the aforementioned 1927 estate apartment, but the humane, the emotional tactility, the sensuousness of life is still his focus. A focus expanded by the question how can machines help us achieve that.

We could go on and on and on and on, we could spend inordinate amounts of time discussing Wilhelm Gutmann's tables, carpets, bookcases, etc, or his variety and variation in and with steel tubing or his use of curtains as temporary walls to divide space; however pressures of time and space mean we can't, but would very much encourage all to engage with the sketches themselves, there is a lot going on, arguably more so than at Lilla Hyttnäs. And to paraphrase Hugo Lang 'boredom cannot arise in studying such rooms'.

Here we have but time and space to quickly note his lighting solutions; solutions that move freely from somewhat antiquated looking lamps to outrageous fantasy constructions that predict the Postmodern bricolage and on to works that seem to know that LED and OLED technology will one day arrive; solutions that include in the aforementioned window space sketch a table lamp in the background that is almost certainly a Rondella Lamp by Christian Dell, arguably Dell's Meisterwerk, the defining lamp of Neues Frankfurt, but which happily finds its place in an interior that for all it is clearly an apartment in a block of flats is an interior far removed from the apartment blocks of Neues Frankfurt. Which tends to underscore the majesty of the Rondella. And a 1927 sketch that features a recurring concept in Gutmann's oeuvre that is one of the genuine highlights, pun intended, of his oeuvre: a rail on the ceiling from which hangs a height-adjustable lamp. A lamp that also appears in, for example, the 1927 estate apartment and a 1930s study; and a lamp, a solution, that for all it without question lacks a little grace in the realisation, has maybe considered steel tubing a little too long, could be, is, in need of a little more refinement, does wonderfully offer the possibility of using the one lamp in a number of ways: one could, for example, have it high in the middle of the room for general light and then when, if, required, move it near a chair/sofa and lower it provide a close up, atmospheric, reading lamp. A reading lamp hanging from the roof that reminds very much of the lighting in Charles and Ray Eames home in Pacific Palisades, a home devoid of floor and table lamps, apart from candles, and which relies on pendant lamps at varying heights. With Gutmann's design concept you, arguably, have a further development of that concept, a further development for interior spaces more restricted than in the Eames house, a further development that brings an increased functionality to an aesthetic solution, combinee the technical with the emotional, and that long before the Eames concept existed.

And all of which leads one to an opinion that in contrast to the popular reception of his art, in his interior and furniture, and lighting, design work Wilhelm Gutmann was not only talented but original; and for all makes one all the more anxious and desirous to see what Wilhelm Gutmann presented at Grassimesse Leipzig 1920.......

.......but as already noted, we no know.

But our search continues.

Yet despite the lack of the all important details, Wilhelm Gutmann's presence at the inaugural Grassimesse in the spring of 1920 is testament to not only the relevance attached to the inaugural Grassimesse by creatives of all genres, but to the event's long standing role in not only the narrative of the development of furniture and interior design, but also in the wider narratives of the development of objects of daily use, craft, applied art and design in context of developments in contemporary society.

A role that, as with the Grassimesse, has continually changed as the contemporary society has changed, and which means that for all the relevance of a Wilhelm Gutmann's contribution to the debates and discourses of the early 20th century, and his ongoing informativeness to contemporary debates and discourses, Wilhelm Gutmann's works probably wouldn't be admitted to Grassimesse 2024.

But yours can.

Regardless of genre.

All you need do, as Wilhelm Gutmann did, is to convince the jury your work is worthy of exhibiting. Whereby Gutmann had to convince first a local Frankfurt jury under the chairmanship of Vincenz Cissarz, and then the main jury. You need but convince the 2024 Grassimesse jury.

Applications for Grassimesse Leipzig 2024 can be submitted until Wednesday May 15th.

Full details, including details of the six Grassi Prizes up for grabs, a sextet that features the €2,500 smow-Designpreis, can be found at www.grassimesse.de

1Adolf Dessler, Die Ausstellung der jungen Künstler in der Modernen Galerie A. Wertheim, Berlin, Das Kunstblatt, Vol. 13, Januar 1929

2see Kunstchronik und Kunstmarkt, Vol 57, Nr 1, Oktober 1921, page 8

3Hugo Lang, Der komfortable Wohnraum, Innen-dekoration, Vol. 38, Nr 7, 1927, page 293 (available via https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/innendekoration1927/0313/image,info Accessed 24.04.2024)

Good Luck!!