While it is popularly appreciated that Art Nouveau in its various dialects was, at least partly, inspired and informed by the natural world, for all the floral world, and also popularly appreciated that the move to more objective, sober, less decorative positions, and dialects, throughout the first decades of the 20th century resulted in a rationalisation of the natural influences of Art Nouveau that tended to remove the direct natural/floral references — if keeping many of the forms such references enabled — it is, arguably, much less popularly appreciated that the move from Art Nouveau to more rational forms of expression in architecture and design in the early 20th century wasn't simultaneously a move away from the natural world as a source of inspiration and information, rather was a move, at least partly, inspired and informed by that same natural world, by that same floral world.

With the exhibition Bauhaus Ecologies the Bauhaus Museum Dessau explore and discuss that role of flora and fauna in the developments of the early 20th century in context of the Weimar and Dessau Bauhauses.......

An exploring, a discussing, undertaken by Bauhaus Ecologies in the course of five, technically six, succinct chapters, opening with Nature as Mode, that formal inspiration and informing from and by nature, that Visualising of the chapter's sub-title, that for all it is popularly associated today with the Art Nouveauists of the late 19th/early 20th century, has, inarguably, long been a factor, has been a factor for as long as human society has been creative. Has long been à la mode as a mode in creativity.

Nature as Mode represented and discussed in Bauhaus Ecologies by, for example, works of glass from the Art Nouveauists Josef Hoffmann, Karl Massanetz and the artisans of Glashütte Loetz in, then, Klostermühle, Austro-Hungary, today Rejštejn, Czech Republic, that serve as a nice link backwards, remind that that which is to come in the exhibition is a component of an ongoing (hi)story not a spontaneous episode in the (hi)story of the human species, isolated, dissociated from other episodes; by a number of books from the late 19th/early 20th century including Moritz Meurer's 1895 work Pflanzenbilder which provided reference sketches of flora specifically intended to serve as models and motifs in applied arts industries, was, if one so will, an analogue 19th century influencer, or Raoul Francé's 1920 Die Pflanze als Erfinder, The Plant as Inventor, a work that opens with France’s ever joyous explanation of how he transformed a poppy seed capsule to a salt cellar. Much as opined from Mimesis. A Living Design at the Centre Pompidou-Metz, Superstudio's 1969/70 Bazaar transformed a poppy seed capsule to a space in which one can sit, made it a room within a room. Two poppy seed capsule projects, two generations apart, that tend to imply while the plant may or may not be an inventor, that which humans do with that which plants employ for their ends is a matter of not only creative perspective, but also of the prevailing political, economic, ecological, social, et al realities in which any given creative finds themselves.

And also Nature as Mode as represented and discussed via a series of photograms of flowers by Bertha Günther realised at Loheland, that female only creative school/community, that expression of female emancipation and self-determination, established near Fulda in 1919. And a Bertha Günther who, as one can read in Bauhaus Ecologies, was an inspiration for a László Moholy-Nagy to begin experimenting with photograms, for all with the photograms of flowers that are presented in Bauhaus Ecologies alongside earlier photograms of flowers by Bertha Günther.

A presentation, a juxtaposition, of Günther and Moholy-Nagy that in addition to allowing one to better appreciate how the various human-centric, naturalistic, positions of the myriad Life Reform movements of the late 19th/early 20th century, in which context Loheland very much existed, pervaded into the more technical, experimental, conceptual positions of the likes of Moholy-Nagy, and that also elucidates why it is so unfair that an institution such as Loheland languishes in the shadows of the Bauhauses, also adds further female contributors to the creative biography of László Moholy-Nagy beyond Lucia Moholy who, as discussed by and from both Lucia Moholy: Exposures at Kunsthalle Praha and Lucia Moholy – The Image of Modernity at the Bröhan Museum, Berlin, was very much a part of those early experiments with photograms, was, inarguably, co-author of the Weimar era photograms, and potentially the later ones, accredited in Bauhaus Ecologies to László alone. A contribution to the photogram as an art form (hi)story, (his)story, has popularly forgotten. Much as it has popularly forgotten Lucia Moholy, Bertha Günther and Loheland. While very much remembering László Moholy-Nagy.

From the nature as a purely formal influence and inspiration for creatives of its opening chapter, Bauhaus Ecologies moves on to explore and discuss how the changing social, economic, technological and for all scientific developments of the early 20th century began to alter the manner in which the natural world, primarily the floral world, influenced and informed creatives.

A discussion and exploration that for us is best illustrated in the chapter Membranes, a chapter that takes its title and impetus from the elucidation and definition in the early 1920s of the cell membrane, including its referencing in Roul Francé's 1923 book Plasmatik. Die Wissenschaft der Zukunft, Plasmatik. The Science of the Future, a book that Francé not only partly wrote in an early 1920s Weimar also inhabited by Bauhaus Weimar, but whose opening chapter is entitled, Der geist von Weimar, The Spirit of Weimar, that position of Weimar as having long been one of the more important centres in the development of culture as a basis for society, of Weimar as the city in which 'the term "European Culture" crystallises'1, and of which Bauhaus Weimar, as Francé himself opines and we readily concur, must be considered as much a component as a Goethe, Schiller, Liszt, et al; and which as a work concerns itself, as the title implies, primarily with the "Lebensstoff", 'live-giving substance', plasma as much as that which keeps plasma bound within cells.

A chapter where one very clearly appreciates a moment in context of nature as an inspiration and instruction for creatives where plants cease to be art and become science; a shift from the whats of the Art Nouveauists' viewing of nature, flora, to whys. Becomes about the structures, systems and processes that enable the expression and function, not the expression and function; becomes an inspiration and instruction based not on observation but on understanding. A shift, we'll argue, that can be considered analogous to the shift in the 18th century when the early systematic botanists such as Carl Linnaeus started to study plants in detail rather than simply look at them as previous generations had. Just the detail in which a Francé et al studied plants was much greater than that in which a Linnaeus et al studied plants, than that in which a Linnaeus et al were able to study plants, and that primarily on account of technological developments and associated developments in scientific understandings. And also the use to which Francé et al studies were put was very different to that which the work of Linnaeus et al was put.

A state of affairs that can be appreciated in Membranes' focus on Siegfried Ebeling and his transposing of the contemporaneous discoveries concerning cells and cell membranes to architecture as described in his 1926 book Der Raum als Membran, Space as Membrane, whose subtitle, 'Is an analytical-critical contribution to questions of future architecture, which goes beyond the mere need and hereby wants to place itself in the creative hand of all science' implies the critical discourse on conventional approaches to architecture it contains, criticisms that include demands for a more interdisciplinary approach to architecture and a more organic approach to architecture, one where the function of a building can be considered more a process that structures support and enable rather than a readily defined physical act that occurs within any given structure. With the associated consequences for the form:function relationship.

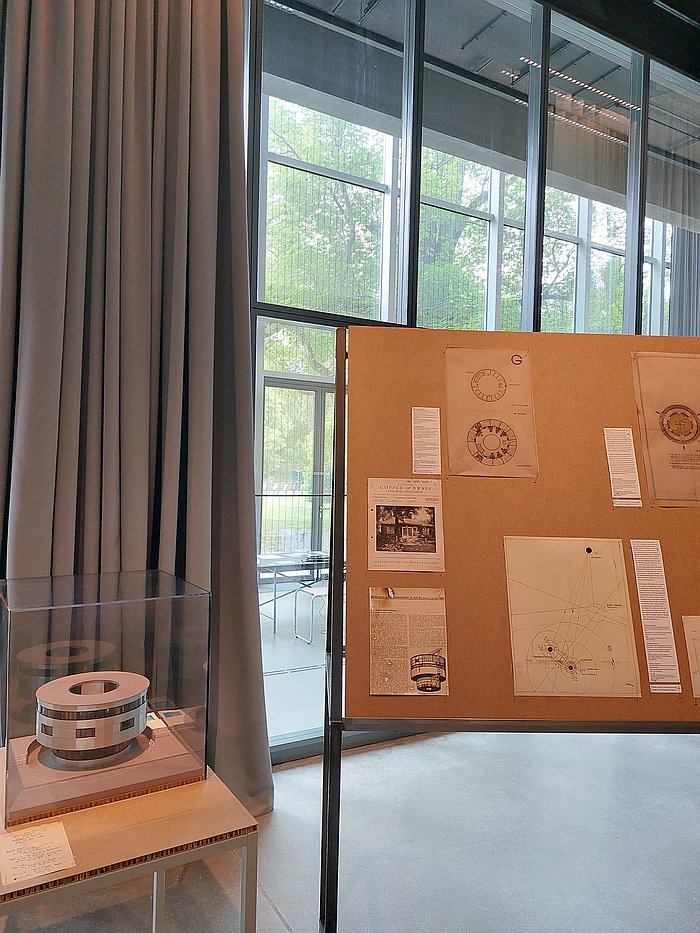

And a 1926 book available in Bauhaus Ecologies for visitors to peruse alongside pages from Ebeling's notebooks that help elucidate the various paths his thinking took, including his focus on subjects such as, for example, interior climate, building biology, building psychology, the interior space as more than pure geometry, subjects that were very much in their infancy in the 1920s; and also Ebeling's ca 1931 plans and models for a rotating round house. Thus a further reinforcement of that argument made by and from Shape of Dreams. The Architecture of Witold Lipiński at the Muzeum Architektury, Wrocław, that the house of the future is always round, as was the house of the past. ¿So why do we live in quadratic houses?

If an early 1930s round house by Siegfried Ebeling whose inclusion of a swastika in the centre of the floorpan, a swastika around which, one can argue, the house rotates, like the earth round the sun, not only forces one to question the future Ebeling envisioned his house existing in, but also the role of not only the many of the more esoteric positions in Ebeling's argumentation that can be followed in Bauhaus Ecologies, but also the many esoteric positions found in the Mazdaznan that was so influential in the early years of the Weimar Bauhaus in the poisonous propaganda that smoothed the NSDAPs rise to power. And thereby also to question the role of Bauhäusler of all hues in the NSDAPs rise to power, as also discussed in and by Bauhaus and National Socialism at Klassik Stiftung Weimar, and thereby approach a more probable, more helpful, appreciation of the relationships between the Bauhauses and 1920s and 30s Fascism.

And a shift from whats to whys, from art to science (and technology) that can also be followed in the chapters Dynamic Nature and Cultivating Nature.

The former with its discussion on the inherent, eternal, vitality and dynamism of nature that increasingly came to the fore in the early 20th century, and that stood diametrically juxtaposed to the static state in which nature had conventionally been approached; a shift from static to dynamic that, arguably, can also be followed in Ebeling's membranes and his proposals on how they could, ¿should?, be applied to architecture. And a Dynamic Nature with a focus very much on the work and positions of Paul Klee, including making reference to Goethe's role in Klee's placing of the natural world at the centre of those positions and works. Thus a further indication, along with Josef Hartwig's 1923 chess set and its use of Goethe's sculpture Stein des guten Glücks with is juxtaposed geometries as the Queen, that it wasn't all antagonism between Weimar Klassik and Weimar Modern in early 1920s Weimar, wasn't all antagonism between the various ages of the "geist of Weimar". If it also was an awful, awful, lot of antagonism. From both sides.

The latter with is focus on green spaces and plants as food, if one so will, plants as something of fundamental physical importance to the human species as well as something of fundamental instructive and informative importance; as something to be actively considered by creatives in the development of their projects rather than something to inspire and instruct those projects. A chapter on Cultivating Nature that introduces the role of Konrad von Meyenburg in the discussions of the period, including the importance of his appreciations of the relevance of Membranes and Dynamic Nature for agriculture, and also his development of a mechanical rotary tiller, a device that in replacing hand-labour in agriculture could have been considered a descendent of the threshing machines et al that caused such violent controversy and rebellion a century earlier, were it not for the fact that the scale of the model depicted in Bauhaus Ecologies implies it was much more intended for the gardens and local level communal, self-sufficiency, production of the period.

Gardens and and local level communal, self-sufficiency very much advanced and enabled in the 1920s and 30s by the work of the ever fascinating Leberecht Migge who one also meets in Cultivating Nature; a Leberecht Migge who, in many regards, and whatever else he is and was, stands very much as a reimagining in a new age of the agricultural colonies of the aforementioned Life Reform movements, and, thus, also of the early Art Nouveauists. Colonies and self-sufficiency that continue to echo in the myriad contemporary communal urban gardening concepts, and other, related, approaches, to ensuring a reliable supply of healthy affordable foodstuffs for urban populations. And thus a further reminder that the journey of human society is one of continuation and re-imagination not of spontaneous, isolated, dissociated episodes; that the only thing that is ever truly new is the context in which a recurring question is posed.

The final chapter, or at least the final chapter of the five chapters in the main narrative, appears, at first glance, to be a very lightweight, almost frivolous, chapter, not least for all familiar with the canon the Comedian Harmonists, titled as it is Cacti: but on closer inspection does prove to be a little more... prickly with its noting of the relationships between cacti and colonisation, between plants and colonisation. That subject, as discussed from Plant Fever. Towards a Phyto-centred design at Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden, and Garden Futures. Designing with Nature at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, that defines so much of the (hi)story of relationships between humans and the floral world, that is a key component of the 18th century work of Linnaeus et al, but that is invariably quickly skipped over in discussions on the (hi)story of relationships between humans and the floral world. ¿Why do plants have the names they do in Europe? ¿Where did those names come from? ¿Where did those plants come from? Thereby making its presence in Bauhaus Ecologies all the more welcome.

A discussion under the title Cacti that also notes that cacti were the only plants allowed in the numerous Bauhaus buildings, all other living flora was (more or less) banned; which is not only a ridiculous state of affairs, but isn't exactly an avant-garde position, certainly not in context of the aforementioned Siegfried Ebeling's considerations on interior climate etc. And a ban that also poses questions about both the healthiness of the Bauhaus environment, of the health of the ecologies at the Bauhauses, as well as the depth of the association with the nature that they were taking inspiration and instruction from: Goethe famously took extreme delight in his garden set in the untamed nature outwith Weimar's city walls, Bauhaus banned plants from within the Weimar buildings.

A discussion on cacti that also features a steel tube and glass plant table designed in ca. 1930 by French architect Émile Guyot a.k.a. Emile Guillot a.k.a. A. Guyat for Thonet. A plant table that wouldn't have been allowed to serve its intended function in the Bauhaus buildings, and that was designed by someone unassociated with the Bauhauses, but which will be lazily labelled today as 'Bauhaus' simply on account of being steel-tube through Thonet; and thereby forces you to question the premise of the term 'Bauhaus' in context of furniture. A question amplified by the object's presence in an exhibition called Bauhaus Ecologies in the Bauhaus Museum Dessau. ¿Why is it there? ¿It's delightful, no question, but why is it there? ¿Is it part of Mehr als echt (More than real) by Jun Yang? ¿Are Thonet missing a trick in not re-releasing for our contemporary ecologies, or perhaps better, more meaningfully, in not re-interpreting, re-imagining, for our contemporary ecologies, the various plant stands by Guyot/Guillot/Guyat and Anton Lorenz, works that in the early 1930s were pitched by Thonet as "Das einzig Richtige für Blumen"2 'The ultimate solution for plants' and potentially still can be?

And if you wanted plant stand to illustrate cacti at the Bauhauses, is the obvious choice not Marianne Brandt's ever joyous cactus stand, one of our personal highlights from the great many highlights of Brandt's post-Bauhaus tenure with Ruppelwerk, Gotha? Yet while that cacti stand, sadly, isn't on show, there is however a picture by Brandt's fellow Chemnitzer Werner Zimmermann of Brandt's atelier in Dessau with Brandt relaxing on the balcony behind a windowsill full of cacti of various ilks. And also a photo by Lucia Moholy of cacti on the windowsill of Walter Gropius's house in Dessau, with nature in its wider variety almost demanding to be let in through the vast windows, much as nature once stood before Goethe's garden in Weimar. Its almost poetry.

And very much a stimulation to delve deeper into the Bauhaus plant ban on your own, one of numerous stimuli Bauhaus Ecologies initiates.

A well-paced, readily accessible exhibition, if one with a lot to read, which is in no way a complaint, far from it, we're all for making exhibition visitors work for their education, it's the only way they'll learn, Bauhaus Ecologies unfolds its narrative via mix of not just books but also art works, archive documents, models, photographs, including in addition to the aforementioned photograms by Bertha Günther and László Moholy-Nagy, works by, for example, Karl Blossfeldt or Ruth Hollós-Consemüller including the latter's shots of cacti at Bauhauses Weimar and Dessau which cause you to question what she could have achieved with a greater variety of plants to experiment with. And also three short films on constant loop that help elucidate not only the subject matter of their respective chapters but also the importance of the development of film as an art and a technology in the developments of the period under discussion; including the 1924/25 film Wachstum der Kristalle, Growth of Crystals, which, as the title implies, demonstrates how crystals grow thereby reinforcing the vitality of the natural world and the need to appreciate the natural world beyond a physical form or colouration discussed elsewhere in Bauhaus Ecologies. And a film, one learns, that was shown as part of the programme for the opening of Bauhaus Dessau in December 1926, thereby allowing an alternative perspective on the context in which that institution took up its work.

An exhibition that very neatly, and very satisfyingly, explains the role of nature, (primarily) plants, in the creative and, by extrapolation, social developments of the period, much as they had done two generations earlier, if in very different manners and contexts. And that thing that, arguably, can also be located in many of the more speculative future projects presented in the aforementioned Plant Fever, not least in those explorations of plant neurobiology, a developing field of enquiry with as yet untold instruction for human society.

A continuation of then in the now and on into the future also very tangible in the sixth of Bauhaus Ecologies five chapters, Co-Weaving with its discussion on and explanations of how microbiological activity, for all as represented by biofilms, can, possibly, contribute to future architecture and design; can contribute to an architecture and design that 'goes beyond the mere need and hereby wants to place itself in the creative hand of all science'.

An exhibition which in its progression from Art Nouveau to speculative futures in the company of the natural world also allows for differentiated reflections on the works presented in the aforementioned Mimesis in Metz. And for all to be better appreciate that while projects featured in Mimesis such as, for example, the Bouroullecs' Algae or Philippe Starck's W.W. stool are very much based on a physical observation of nature that reminds of the Art Nouveauists, the presented projects by the likes of, for example, Ross Lovegrove, Neri Oxman, Klarenbeek & Dros or Marlène Huissoud are and were more reliant on contemporary scientific understandings and approaches akin to the developments of the 1920s discussed in Bauhaus Ecologies, tend to echo a Siegfried Ebeling's Membranes or a Paul Klee's Dynamic Nature, while Tokujin Yoshioka's Venus chair from 2008 is literally the result of the Wachstum der Kristalle. And thereby allows one to much better appreciate the progression of creativity as a cumulative, augmentive process, one where that which was isn't replaced by the new but rather the new adds to the existing.

Thus elucidating why the same natural world, the same floral world, influenced and instructed both the Art Nouveauists and those later generations who rejected and moved on from their positions and approaches. And continues to influence and instruct us. And will continue to do so as long as we have a natural world, a floral world. Thereby highlighting the urgent need to be more considerate in our dealings with the natural world, the floral world. We really do need it. And not just to look at and paint.

While away from its primary focus, and the very satisfying and entertaining manner in which it approaches that focus, the fact that Bauhaus Ecologies as a presentation is devoid of the great many conventional and ubiquitous Bauhaus artefacts and narratives, doesn’t contain anything you'd ever find in any of the great many near identical Bauhaus coffee table books or being endlessly echoed, unquestioned, unchallenged, on social media and that will soon become carved in AI stone, very satisfyingly forces you to engage with the (hi)stories and legacies of the Bauhauses afresh, without any of the safety nets and crutches normally employed when approaching the Bauhauses. It is without question an exhibition based in the Weimar and Dessau Bauhauses, but isn't instantly recognisable as such.

And in doing so and being such reinforces that the Bauhaus ecosystem is and was much more complicated than the monoculture it is so often presented as being. And importantly does so in the year of Bauhaus Dessau's 100th birthday thereby aiding and abetting the telling of that more probable narrative of the (hi)story of the Bauhauses we desperately need. Aiding and abetting more probable appreciations of what the Bauhauses were, and what they can be, if we let them, if we free them from their chains.

A process one can begin oneself upstairs in Bauhaus Museum Dessau's permanent exhibition, a presentation the fresh perspectives enabled in and by Bauhaus Ecologies allows you to not only view differently than you otherwise would, but also allows you, empowers you, to see things you may otherwise not have recognised. A reminder of the importance of continually learning to view things differently: be that the Bauhauses, the natural world, or our relationships with the ecologies in which we all exist.

Bauhaus Ecologies is scheduled to run at Bauhaus Museum Dessau, Mies-van-der-Rohe-Platz 1, 06844 Dessau-Roßlau until Sunday November 2nd.

Further details can be found at https://bauhaus-dessau.de

And until Sunday October 19th Kang Sunkoo - Sacristy can be viewed at the Bauhausgebäude, Gropiusallee 38, 06846 Dessau-Roßlau.

1Raoul Francé, Plasmatik. Die Wissenschaft der Zukunft: Mit zwölf Original-Federstichen des Verfassers, Walter Seifert Verlag, Stuttgart/Heilbronn, 1923 page 9

2Thonet Stahlrohrmöbel 1934 catalogue, as seen in Bauhaus Ecologies Also available online via https://hauspublikationen.mak.at/viewer/toc/AC142/