Mies im Westen @ Landeshaus des LVR, Cologne

While Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is arguably best known for the works he realised in the (mid-)west USA, the works he realised in west(ern) Germany are no less relevant or important for understanding the man, his work and his legacy.

Summer 2019 saw the western German State of Nordrhein-Westfalen host three Mies van der Rohe exhibitions, one each in, and devoted to Mies’s works in, Aachen, Krefeld and Essen. Three exhibitions now united in one in Cologne, and which as a unified trio not only provides for a very concise overview of the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Nordrhein-Westfalen, but also of both the development of Mies van der Rohe as an architect and, in many regards, the wider developments in understandings of architecture and design in the course of the 20th century.

Maria Ludwig Michael Mies a.k.a Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, was born on March 27th 1886 as the son of the stonemason Michael Mies and his wife Amalie, nee Rohé, in Aachen. A fact that always makes us smile. Not sure why. Not sure why his being from Aachen should amuse us. Nothing against far Aachen, far from it. And Aachen was, is, after all the city of Charlemagne, the city where for 600 years the Holy Roman Empire crowned its Kaisers and also the centre of the German marzipan and chocolate industries. Aachen is a city long associated with the illustrious. But that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was born in Aachen, that amuses us.

And it is also in Aachen the Mies van der Rohe’s architectural career and the exhibition Mies im Westen begin: Mies’s career with studies at the local vocational and applied arts schools, and an apprenticeship in the office of Albert Schneiders; the exhibition Mies im Westen with his contributions to the former Tietz department store on the city’s historic Markt and the cafe/bar/meeting place Zur Neuen Welt in the Alexanderstrasse. The former realised in 1904/05 by Albert Schneiders, its pointed gables, central steeple-esque tower and highly ornate facade very much reflecting the confusions of historicism; and a work to whose highly ornate facade we learn Mies van der Rohe used his artistic talents and training in ornamental draughting to contribute numerous, intricate, details. Beyond that facade however the interior was based around a much more practical, rational, and contemporary design and construction: the facade being literally just that, and thus a very neat example of understandings of architecture, design, ornamentation and representation that Mies van Rohe would do much to deconstruct. And also a further indication of the relevance and importance of the Tietz department store chain to the development of architecture in Germany, and by extrapolation the world: in the early decades of the 20th century the department store was a relatively new concept in Germany, Leonhard Tietz being one of the pioneers, and making use of architects converse with contemporary thinking to develop his stores, Wilhelm Kreis building those in Wuppertal and Cologne, while Joseph Maria Olbrich beat off competition from Peter Behrens to develop the Düsseldorf dépendance. And as Mies im Westen explains Schneiders’ first proposal for Aachen also featured a more, let’s say, rational, reserved, Jugendstil ornamentation; the authorities in Aachen however wanted a more fulsome pomp, something better reflective of the decorative overload of Aachen Rathaus, and thus Schneiders adapted his design to the location.

That Tietz Aachen was demolished in 1965 we only have photos, models, sketches et al to remind us of not only the structure but of Mies van der Rohe’s architectural education; Zur Neuen Welt by contrast still stands. Referred to by the curators as the first building to which Mies van der Rohe actively contributed, Zur Neuen Welt was developed parallel to the Tietz department store and is much more in keeping with Schneiders’ original plan for Tietz, is a much more reduced affair, a work which makes use of the basic elements of classical Greco-Roman architecture, albeit much more as an indication than an intention, are implied to assist the defining of the facade rather than enacted for decoration and representation. In many regards the only decoration is the lettering over the entrance, and that in a font which the curators claim was devised and developed by Mies van der Rohe, and which is very much of an early 20th century Jugendstil.

In 1905 Maria Ludwig Michael Mies left Aachen for Berlin, where his popular biography begins: first in the applied arts school with Bruno Paul, subsequently with Peter Beherns in Babeslsberg, his own studio in Berlin, the adoption of the name Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the Weißenhofsiedlung Stuttgart, the Bauhauses in Dessau and Berlin and his emigration to Chicago and the oft discussed (mid)-west Mies van der Rohe.

Mies im Westen reminds us that his varied activities in his native Rheinland are every bit as important to that biography.

If Zur Neuen Welt provides an indication of a direction in which the young Mies could have been considering moving when he left Aachen, the new world he was visualising, the works he both planned and realised in Krefeld in the 1920s and 1930 provide evidence of the journey he undertook, evidence of how his understanding of architecture developed in Berlin. While contemporary Krefeld may appear an unlikely place for the likes of a Mies van der Rohe to be developing projects, it is no more unlikely than a Henry van de Velde developing projects in Chemnitz: one must simply remember that times change and that Krefeld was once one of the most important centres of textile production in Germany, a tradition that stretches back to the 18th century and a monopoly granted by Friedrich II, and a tradition whose depth allows Krefeld to still refer to itself as the city of Samt und Seide, velvet and silk.

Materials with which Mies van der Rohe is only rarely directly associated but which are not unimportant in the development of his career: as we learned from the exhibition Anton Lorenz: From Avant-Garde to Industry at the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot it was on a trade fair stand designed by Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich for the Krefeld silk weavers that Lorenz first saw Mies’s cantilever chairs, and first understood the potential inherent therein. And in the late 1920s and 1930s Mies not only built houses in Krefeld for Hermann Lange and Josef Esters, two co-founders of the company Vereinigten Seidenwebereien, United Silk Weavers, but also developed a factory for Vereinigten Seidenwebereien, or perhaps better put developed a factory site for Vereinigten Seidenwebereien. Unrealised remains Mies’s administrative headquarters for Vereinigten Seidenwebereien, a project developed in 1937/38 by Mies in conjunction with Erich Holthoff and Herbert Hirche but which on account of the immense material requirements of the NSDAP and their pre-war infrastructure projects, and associated immense material shortage for everyone else, was never realised. Or at least not realised as Mies van der Rohe’s design, and not until after the war when Egon Eiermann realised a much smaller, if every bit as quadratic, open, glass and steel construction on the same site. If Mies was asked to complete the work, we no know; we do however know that while Eiermann was busy building in Krefeld, Mies was developing the Illinois Institute of Technology, IIT, campus in Chicago. And thus developing the (mid-)west Mies.

Equally unrealised remains a club house Mies van der Rohe developed in 1930 for Krefeld golf club; a sprawling, low-level proposition which in many regards reminds one of an extended and meandering re-imagining of his Barcelona Pavilion, while the way it appears to be designed to not only sit unobtrusively in its surroundings but to directly communicate with them implies an extended and meandering forbearer of his Farnsworth House in Illinois. And a project which also reminds us that Henry van de Velde built a tennis club in Chemnitz. And that it was very different days back then.

Krefeld Golf Club by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

In Krefeld Mies van der Rohe built for the production of velvet and silk, in Essen Mies van der Rohe built for the harder end of Rheinland industry: steel. Or more accurately put, planned for the harder end of Rheinland industry: much like his administrative headquarters for Vereinigten Seidenwebereien was never realised, a project commissioned by the Friedrich Krupp AG in 1960 for new administrative headquarters in Essen never got beyond the blueprints. The reasons appear lost in the mists of time, or possibly the depths of the Krupp archives, all Mies im Westen can confirm is that in 1963 the company zurückgestellt, shelved, the project. And as discussed in our Shelving playlist, that which is placed on a shelf, rarely leaves it.

Similarly a planned construction for the VEGLA Vereinigte Glaswerke Aachen remains unbuilt, largely, though not exclusively, on account of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s death on August 17th 1969. The planning had begun in 1968 and had reached an advanced stage by the time of Mies’s death, the VEGLA however deciding to develop an alternative proposal by Düsseldorf based HPP and thus, in effect, passing up the chance to have Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s last work not only in the city of his birth, but in the city of his first work. Rarely would an architectural circle have been so perfectly completed.

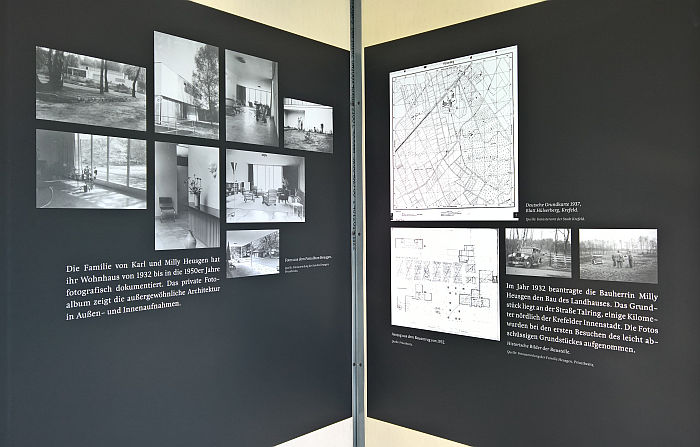

Or perhaps it was, for if that circle is in fact a spiralling helix of architectural history then the choice of HPP, and thereby architects who in many regards owe a huge debt to Mies van der Rohe, indicates the importance, influence and legacy of Mies van der Rohe. An importance, influence and legacy discussed further in Mies im Westen through a number of post-War works by other architects in Nordrhein-Westfalen including Paul Schneider-Esleben’s Mannesmann Hochhaus in Düsseldorf, a project in the preparation of which Schneider-Esleben travelled to America to meet Mies and study his construction systems; Essen Rathaus by Theodor Seifert, Haus Heusgen in Krefeld by Rudolf Wettstein & Willi Kaiser or the Landeshaus des LVR in Cologne by Eckhard Schulze-Fielitz, Ernst von Rudolf and Ulrich Schmidt von Altenstadt, and which hosts the exhibition: a late 1950s glass, steel, concrete work in Cologne-Deutz, and raised up on stilts as if to allow a better view across the Rhein to Cologne Cathedral. And which through the number of homeless camping in its inner courtyard reminds us that despite all the social interventions and proposals of architects over the decades, we are still a long way from true social justice. That obviously isn’t the fault of architects alone, politicians, and indeed us all, have an important responsibility there too; but if you set yourself up as being able to use your training and vision to make our world not only aesthetically pleasing, but a better, fairer place, you will be measured on your results. And in how far did the inter-War Modernists actually achieve that? Zur Neuen Welt still standing not only as a building but an unfulfilled vision. But we digress….

Documentation of Haus Heusgen, Krefeld by Rudolf Wettstein & Willi Kaiser, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

Realised by the M:AI, Museum für Architektur und Ingenieurkunst NRW, in conjunction with students from the TH Köln, TH Mittelhessen and the Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, Mies in Westen presents photos of, sketches of and documents relating to 16 projects, 10 by Mies van der Rohe, 6 by others; each project being given its own T-shaped panel island, T-shapes made possible by the application of a construction principle developed by Mies van der Rohe and employed in his skyscrapers. Models of the projects placed down the middle of the exhibition space allow for a 3D visualisation of both work and setting, while the accompanying booklet not only serves as a handy reference for visiting the still extant works, but implores you do just that, that the exhibition shouldn’t be understood as the end of your journey of discovery through Mies im Westem, but that start.

A pleasingly approachable, accessible exhibition, albeit one regrettably only in German, the relevance and appeal is much wider, Mies im Westen neatly demonstrates that it is possible to stage an architecture exhibition without technical jargon or pretentious bobbins, one can simply discuss and describe a building in its character, context and construction, and in doing so allows even the most layest of lay visitors to approach a better understanding of the career of Mies van der Rohe, the work of Mies van der Rohe, the legacy of Mies van der Rohe, and to better understand that achieving that involves considering not only the skyscrapers of downtown Chicago or New York, but also the family homes, factories, conservatories, department stores, and golf clubs, of Essen, Krefeld and Aachen.

And thereby that the (mid-)west USA Mies van der Rohe was heavily influenced by, and heavily influenced, the west(ern) German Mies van der Rohe. That the two are one.

Mies im Westen runs at the Landeshaus des LVR, Kennedy-Ufer 2, 50679 Cologne until Monday November 11th. Entrance is free.

Full details can be found at https://mai-nrw.de/mies-im-westen

- Haus Hermann Lange in Krefeld by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

- Haus Hermann Lange in Krefeld by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

- Photos and plans of Zur Neuen Welt Aachen by Albert Schneiders & Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

- The proposed Vereinigten Seidenwebereien HQ in Krefeld by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

- Part of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s plan for the Vereinigten Seidenwebereien HQ in Krefeld (l) and photos of the work as realised by Egon Eiermann, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

- A model of the proposed VEGLA Vereinigte Glaswerke Aachen HQ by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

- Krefled Golf Club by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

- A model of the Leonhard Tietz department store Aachen by Albert Schneiders (with the assistance of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe), as seen at Mies im Westen, Landeshaus des LVR Cologne

Tagged with: Aachen, Alanus Hochschule für Kunst und Gesellschaft, cologne, Essen, köln, Krefeld, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, M:AI, Mies im Westen, Museum für Architektur und Ingenieurkunst NRW, Nordrhein-Westfalen, TH Köln, TH Mittelhessen