Grassimesse Leipzig 1920 Compact: Gertrud Lincke – Interior Design and Furniture

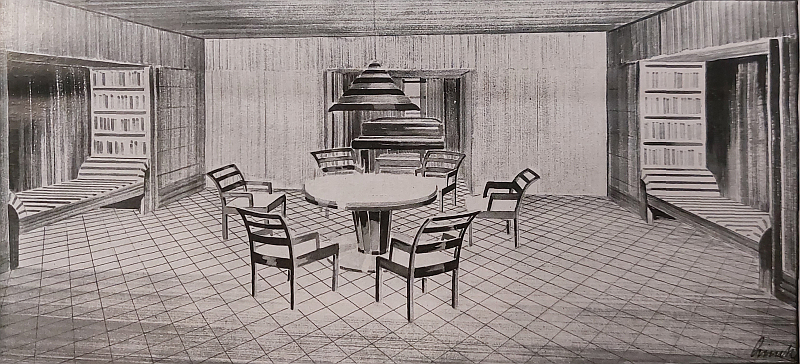

A living room design by Gertrud Lincke featuring two Arbeitskojen, Work Bunks/Berths, on the left and right, home office à la the 1920s (undated, but before 1927, possibly 1924/5)

In 1926 the Dresden based architect Gertrud Lincke will opine that “women are decisive, paramount, when it comes to setting up a home”, and that not because of what you think, but because, “they are the most negatively impacted by the housing crisis and all that comes associated with it”. However, she will lament that, “only very few are aware that in terms of their homes they are being dictated to by speculators whose main goal is to make bad things seem good and cheap. In order to achieve better housing it is necessary for women to set out conditions and demands that must be met by the state and developers, by the construction and furniture industries when realising residential buildings and furnishings”. And that not least because, for Lincke, “the layout and design of the apartment is not just a question of taste, but the current and future state of the entire culture, the health, strength and efficiency of the population depend on it.”1

Born in Dresden on June 6th 1888 Magdalene Gertrud Lincke enjoyed a, one presumes, comfortable childhood in the Sächsische Metropole, her earliest years are, even from this short distance, sadly lost in the thick mists of the upheavals of the late 19th century; what is known is that in 1908 she was enrolled in the Schülerinnenabteilung, Female Department, at the Königlich Sächsischen Kunstgewerbeschule, Dresden2, a Schülerinnenabteilung that, as previously noted, opened in 1907 as a component of the reformed, egalitarian, attitudes towards gender that have become so commonplace of late. And a Schülerinnenabteilung in which Lincke initially studied within the Graphic Applied Arts class before in 1912 switching to Margarete Junge’s class with its focus on ‘designing and executing female artistic handicrafts and clothing, as well as draughting of architectural applied arts’. And thus to a Margarete Junge who, as previously discussed in these dispatches, has been such as an important figure in furniture design in these first years of this new century, including contributing to the rise in recent years of Dresden as a leading international centre of contemporary furniture design and production, but a Margarete Junge who (hi)story will unjustly forget as she is not a man, and that despite the great advances in terms of gender equality we’ve all made, and the new types of dresses that have been developed; a Margarete Junge who, if she isn’t already, those mists of time again, will become the first female Professor in Sachsen, and who is such an important and influential educator in these first years when females are allowed to study, whereby her influence, or lack of, on Gertrud Lincke is, given current realities, difficult to assess. That is however something for future generations to explore. And a teaching by Margarete Junge of ‘architectural applied arts’ in the Schülerinnenabteilung that, again, as previously noted, opens a faint crack in the door of possibility that could lead to the fact that the female students were allowed to, empowered to, design furniture. And not just cushions. And dresses. A very faint crack, but one well worth pushing at. Not least on account of the light it could shine on Margarete Junge.

And on Gertrud Lincke. And that very relevantly in terms of Lincke given the fact that following the end of gender segregated teaching at the Dresden Kunstgewerbeschule in 1915 — as previously noted, and which we do again here because it tickles us, an ending of gender segregated teaching in Dresden in 1915, and thus four years before it was introduced at Bauhaus Weimar — following the end of gender segregated teaching at the Dresden Kunstgewerbeschule in 1915 Lincke switched to the Raumkunst, Spatial Art, Interior Design, class, where she remained until 1917, when one presumes, and after some 9 years, she left the Kunstgewerbeschule Dresden and began her professional career as an architect. A profession she hadn’t learned but which is one she not only has an all too obvious passion for, but a very interesting and informative perspective on and position to.

An architectural career, passion and perspective that in the coming years will see Gertrud Lincke contribute to debates and discourses on affordable housing in context of the housing crisis that has become so apparent in recent years, and for all Lincke will concentrate on affordable, hygienic, meaningful, accommodation solutions for elderly females and single females, groups greatly impacted by the demographic damage of the recently concluded War; a debate that for Lincke will be as much about financing house building and ownership as with the forms such buildings should take: that simple argument that what is the point in hygienic, safe, meaningful, energy efficient, climate neutral, housing if no one can afford it, a question that will echo on through the coming decades. Arguments for affordable, hygienic, meaningful housing that will see Lincke become a proponent of and advocate for, amongst other innovations and novelties, industrial serial construction as the only rational way forward, an argument that will include regular demands for the use of steel skeleton construction, demands for the flat roof and demands for flexible and removable partition walls by way of allowing responsiveness in interiors, the latter an oft overlooked aspect of that architecture which will develop in the 1920s and 30s and which will find an echo in the 1970s and then fade, despite the apparent obviousness of the solution. And will also see Lincke reject communal kitchens in housing estates3; communal kitchens that a great many of her contemporaries will not only demand but realise throughout the 1920s and 30s.

Views on kitchens that can be considered as a component of Gertrud Lincke’s contribution to debates and discourses on the interiors of homes in the coming 1920s and 30s; a contribution that will see her denounce, and be frustrated by, a maintaining of the existing, the familiar, through “convenience and laziness of thought”; a position, denouncements, that will find an echo much, much later in Denmark in a Nanna Ditzel’s “don’t we carry around a whole load of stuff that is old and defunct – and could actually be different.”4 A contribution to debates and discourses on home interiors that will see her demand furniture that should express itself via “lowest weight, easy mobility and easiest to manufacture”, demanded more hygienic materials from the textile industry, and argue for belted upholstery rather than cushions for soft furnishings. And also see her opine that “until industry has invented a new material for furniture that is malleable, lighter and more durable than natural wood, thinner wood constructions and thinner plywood will have to be used”, and thereby allowing one to not only appreciate the reductions and rationalisation she demanded in furniture as much as a compromise as a position, and also to appreciate her belief in the important role of technological developments in enabling novel forms of domestic arrangements, much as steel could, must, contribute to architecture and construction, but also sees her not only predict synthetic plastics, but appreciate why synthetic plastics are advantageous in context of furniture design. Without being able to foretell, as no one can in 1920, the problems human society’s reckless, selfish, uncontrolled, use of plastics will bring. Positions on interiors that will see her reject furniture crafted from aluminium, sheet steel and tubular steel, and instead envisage, dream of, an “artificial wood” that has “all the advantages of natural wood and metal without uniting their disadvantages”. If she could see the 3D printed wooden furniture that will be possible in coming centuries, she’d probably dance for joy. And will also see her express very clear opinions and ideas about the use of colour in domestic spaces, the essential and fundamental role of colour in domestic spaces, but that is for another day.

Positions and approaches that will be reflected in a very small number of realised projects, including her interiors for Gustav Lüdecke’s Handarbeiter and Kopfarbeiter, manual labourer and office worker, houses that will be presented at the 1925 Wohnung und Siedlung exhibition in Dresden, and also a home for female pensioners realised for the Frauenwohnungshilfe that will be opened in 1928 on Dresdens’ Gabelsberger Straße, and which will not only reflect a very rational, reduced formal expression, will reject representation through ornamentation and demand usability and functionality, while remaining a visually engaging and communicative construction, an engaging and communicative construction that 100 years after its realisation will still feel fresh and relevant; if a construction in brick rather than the steel skeleton the basic form was, inarguably, originally conceived in. A home for female pensioners that will not only feature private kitchens, as one would expect, and a number of other innovations currently only barely imaginable, but will also feature in-built wardrobes, another oft overlooked principle of the coming 1920s, and which will predict the so-called Storagewall concept with which a George Nelson will make a name for himself in America. And a home for female pensioners that will be just one of several projects to be realised in Dresden by Lincke in the 1920s and 30s for the Frauenwohnungshilfe and other similarly socially focussed organisations.

Before an event of which we cannot speak, but of which future generations must speak before it happens again, will derail her career, as it will derail many careers, a derailment, and a subsequent citizenship of a county the future Germany will pretend was only a shadow of the perceived real Germany that was to be found in the west of the region currently occupied by Deutsches Reich, and thereby refuses to take the former eastern component’s culture seriously, will see no-one trace her legacy, as it will see no-one trace the legacy of Margarete Junge, who like Lincke will live a quiet post-1945 existence in Dresden, unnoticed, and will slowly slip into a thoroughly unfair, undeserved, anonymity.

That is however all still to come, is a biography still to be written, and the path to that future leads over the 1920 Grassimesse Leipzig where Gertrud Lincke presented…….

…….we no know.

Sorry. We can find no record of what Gertrud Lincke presented at that inaugural Grassimesse, a lack of detail, a void, that poetically echos, as only a void can echo, the place Gertrud Lincke should take in the popular narrative of furniture and interior design (hi)story, and also in the popular narrative of architectural (hi)story being as she was a voice in an age when female architects’ voices were rare and seldom articulated, an architect’s voice that spoke for females in questions of architecture and urban design and not at females, as men tend(ed) to. Whereby, yes, as Claudia Quiring rightly notes5 much of that which Gertrud Lincke published was in magazines for women that most of the male architecture community would have taken little heed of; but, we’d argue, who else was talking directly to those females who didn’t read the patriarch’s architecture magazines about, for example, the positions of a Le Corbusier, discussions on steel construction, the state of the furniture industry, the complexities of financing house construction, the politics of housing and furniture, the cultural significance of housing and furniture, etc, etc, etc. Arguably no-one else, at least not with the elegance and accessibility and research of a Gertrud Lincke. And that regardless of whether one agrees with her positions, or not.

Yet despite the lack of the all important details, Gertrud Lincke’s presence at the inaugural Grassimesse in the spring of 1920 is testament to not only the relevance attached to the inaugural Grassimesse by creatives of all genres, but to the event’s long standing role in not only the narrative of the development of furniture and interior design, but also in the wider narratives of the development of objects of daily use, craft, applied art and design in context of developments in contemporary society.

A role that, as with the Grassimesse, has continually changed as the contemporary society has changed, and which means that for all the relevance of a Gertrud Lincke’s contribution to the debates and discourses of the early 20th century, and her ongoing informativeness to contemporary debates and discourses, Gertrud Lincke’s works probably wouldn’t be admitted to Grassimesse 2024.

But yours can.

Regardless of genre.

All you need do, as Gertrud Lincke did, is to convince the jury your work is worthy of exhibiting. Whereby Lincke had to convince first a local Dresden jury and then the main jury. You need but convince the 2024 Grassimesse jury.

Applications for Grassimesse Leipzig 2024 can be submitted until Wednesday May 15th.

Full details, including details of the six Grassi Prizes up for grabs, a sextet that features the €2,500 smow-Designpreis, can be found at www.grassimesse.de

Good Luck!!

1. And all other quotes unless otherwise stated, Gertrud Lincke, Über die Mitarbeit der Frauen bei der Aufgabe: Wie schafft man billige und desunde Wohnungen?, Deutsche Frauenkleidung und Frauenkultur, Vol. 22, Nr 7, 1926, 204-209

2. For more detail, and context, on Gertrud Lincke’s biography see Claudia Quiring, Städtebau, Soziales und Stahl. Die Dresdner Architektin Gertrud Lincke, in Claudia Quiring & Hans-Georg Lippert [Eds.], Dresdner Moderne 1919-1933. Neue Ideen für Stadt, Architektur und Menschen, Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2019, 223-233

3. See, Gertrud Lincke, Wohnungsbau, Die Frau, Vol. 33, Nr. 11 August 1926, 674

4. Nanna Ditzel in the 1961 TV interview Hjemme hos: Nanna Ditzel / At home: Nanna Ditzel, as shown in the exhibition Nanna Ditzel. Taking Design to New Heights at Trapholt, Kolding. We can’t find anywhere it else, but it may be out there somewhere…….

5. See, Claudia Quiring, Städtebau, Soziales und Stahl. Die Dresdner Architektin Gertrud Lincke, in Claudia Quiring & Hans-Georg Lippert [Eds.], Dresdner Moderne 1919 – 1933. Neue Ideen für Stadt, Architektur und Menschen, Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, 2019, 227

Tagged with: Dresden, Gertrud Lincke, Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Grassimesse, Leipzig