Unknown Modernism @ the Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

As this Bauhaus Weimar centenary year is making ever clearer, whereas Bauhaus may have been physically sited in Weimar, Dessau and (nominally) Berlin, approaching a better understanding of “Bauhaus” involves leaving those sites and following the many paths that either led to, or from, those sites.

Paths that not only allow one to approach a better understanding of “Bauhaus”, but for all to approach a better understanding of the wider developments of the inter-War years, of inter-War Modernism, and thus to better understand that Bauhaus was but a component of that period, but a component of inter-War Modernism.

And paths, such as those mapped by the Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, that invariably lead to new places, to new understandings and to an Unknown Modernism………

Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

Not that inter-War Modernism is completely unknown in Brandenburg, to claim such would be preposterous, certainly in terms of architecture, interior design, textile design and furniture design Brandenburg can and does boast several well known inter-War Modernist projects including the ADGB Bundesschule in Bernau by Hannes Meyer & Hans Wittwer, the Waldfriedhof Luckenwalde by Richard Neutra, the Einsteinturm in Potsdam by Erich Mendelsohn, arguably Konrad Wachsmann’s summer house for Albert Einstein in Caputh, the Dieselkraftwerk in Cottbus……….

………..Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus?

Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus.

???

Commissioned in 1926 by Cottbus municipal authority on account of the increased electricity demand of the 1920s, and thus indicating the building of the Trotha power station in Halle wasn’t an isolated incident, that the Roaring Twenties were a period of exponentially, roaringly, increased electricity consumption, the Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus was built in 1927/28 by Werner Issel, and, by popular acceptance, was one of the most modern power stations in Germany: as in technically modern, but also figuratively, presenting itself as it does with a very modern formal aesthetic, an articulation informed by historic, classic, archetypes but much more rational, objective if every bit as expressive. And much as the former Bankside Power Station in London became the Tate Modern, so the former Dieselkraftwerk in Cottbus became the Brandenburg Modern, the Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, BLMK.

And a site of a tour through unknown, and slightly better known, aspects of Modernism. A tour undertaken in five parallel exhibitions across the BLMK’s sites in both Cottbus and Frankfurt (Oder), five exhibitions which tackle different aspects of Modernism in both Brandenburg and more generally, five exhibitions with the collective aim of exploring the evolutions, tensions and legacies of the inter-War years, in both Brandenburg and more generally. And five exhibitions that would be way too much for one post, and so we begin in the Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus and the exhibitions Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild, Im Hinterland der Moderne and Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg.

Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg

Bauhaus in Brandenburg is often reduced down to the aforementioned ADGB Bundesschule in Bernau, a work which although predominantly developed, inside and out, at Bauhaus Dessau, also featured input from staff and students at Burg Giebichenstein Halle; and therefore neatly underscores that the search for Bauhaus is more often than not a search for an expression of the 1920s and 1930s, Bauhaus being as it was an (evolving) approach to an understanding of form, function, aesthetics, creativity, production etc, etc, etc that both absorbed external influences and disseminated new impulses, and as such had numerous expressions.

Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg explores such expressions through the work of 9 creatives, in 7 locations and 4 genres: craft, industry, publishing and education.

As an exhibition Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg has no natural starting point, has however a logical starting point, craft, that which played a central role in the early days of Bauhaus Weimar, the early days of the Bauhaus story, and as represented in Cottbus by the likes of the Steingutfabriken Velten-Vordamm or Haël-Werkstätten für Künstlerische Keramik in Marwitz: the later founded by Margarete Heymann-Loebenstein in 1923, following her departure from the Bauhaus Weimar ceramics workshop in Dornburg and, and on account of her Jewish ancestry, relinquished under pressure/insistence from the NSDAP in 1934. The former initiated by Hermann Harkort, a close associate of the Deutscher Werkbund, a cousin of the Hagen based art collector, patron of Peter Behrens and Werkbund driving force Karl Ernst Osthaus, and which employed the services, of amongst other ceramicists and ceramic artists, the Bauhäusler Theodor Bogler, represented in Cottbus by, and amongst other works, examples of kitchenware he created for the Haus am Horn in Weimar, and Werner Burri, who after his tenure in Velten cooperated with Hedwig Bollhagen in the HB-Werkstätten für Keramik; which Bollhagen famously formed in 1934 after acquiring Heymann-Loebenstein’s “abandoned” Haël-Werkstätten, the abandoned Schreckenskammer – Chamber of Horrors – as the NSDAP newspaper “Der Angriff” so objectively reported events.

Things were, as far as we can ascertain, much more harmonious at the Freiland-Siedlung Gildenhall near Neuruppin, a town that through its boast of being the birthplace of both Theodore Fontane and Karl Friedrich Schinkel is arguably home to more famous Brandenbürger than any other, and an artists colony which existed, more or less, in the spirit of the reform movement, those proto-hippies who did so much, so much unacknowledged, to inform what became Jugendstil, and who’ve never really gone away; and an artists colony based in an areal designed by Otto Bartning, with, we learn, the interior of the associated children’s home being designed by the official unofficial Bauhaus Weimar successor, the Staatliche Bauhochschule Weimar, of which Bartning was Director and which included amongst its staff the likes of Wilhelm Wagenfeld and Erich Dieckmann, and an areal which provided a home and workspace to the ex-Bauhäusler Eberhard Schrammen and Else Mögelin.

Inevitably a student at the Bauhaus Weimar Women’s Department Weaving Workshop Else Mögelin is known, if at all, through her larger works, including the two wall hangings which formed part of the exhibition Bauhaus. Textiles and Graphics at Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz. In Cottbus one can experience more modestly sized works by Mögelin including clothes and an absolutely joyous small toy donkey, and works which allow for a fresher, deeper, insight into her oeuvre. Or perhaps more accurately put, an insight into her oeuvre.

Eberhard Schrammen, not only one of the earliest Bauhaus Weimar students, but a student of the predecessor institute, the Großherzoglich-Sächsischen Hochschule für bildende Kunst, is represented in Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg by photos, wood carvings and a collection of furniture from ca 1925 which although on first impressions appear anything but unassuming are, on a closer, more considered, inspection, nicely reduced, unassuming objects constructed from a repetition of simple geometric forms, and thus in many regards represent a very rational interpretation of the strict geometric teachings at Weimar. A taming of the abstract if you will. As, indeed, is Wagenfeld and Junker’s “Bauhaus” lamp.

Both Else Mögelin and Eberhard Schrammen moved to Gildenhall after having declined to move with Bauhaus from Weimar to Dessau, a decision, one presumes, made because they had little interest in the move from craft to industry that such a move, whatever else it implied, more or less implied.

Very much interested in industry was however their Weimar colleague Christian Dell.

Photos by Eberhard Schrammen and ceramics by Margarete Heymann-Loebenstein, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

As previously noted, quite aside from his skill as a silversmith Christian Dell was one of the world’s first plasticsmiths developing a whole world of objects for Spremberg based H. Römmler AG. That we’ve discussed Dell’s plasticsmithery previously we refer you dear reader to that post, if you be interested, which you should be, in Cottbus you can see, and enjoy, his 1929 Pheonplast Lamp, the first desk lamp crafted from a synthetic material and an object produced by Römmler and distributed by Frankfurt (Main) based lighting company Kontakt, and which stands alongside a Russian copy, a near 1:1 copy which has become more famous than Dell’s original, and a lamp, we learn, that graced Stalin’s summer house in Kunzewo. Presumably before Stalin developed such an allergic affliction to Imperialist Modernism. In addition to examples of Dell’s metal lamp designs, works which neatly indicate the formal parallels between his plastic and metal lamps, Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg also presents further examples of Dell’s varied plastic work for Römmler, for all those objects that stack, largely inside one another, to allow for ease of storage in confined spaces and/or for transport, and a stacking concept one also finds repeated in numerous glass creations realised by Wilhelm Wagenfeld for the nearby Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke in Weißwasser.

We’ll be honest, we always thought Weißwasser was in Brandenburg. We learn from Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg that Weißwasser is, in fact, in Sachsen. That however it used to be in the region administered from Cottbus it is included, somewhat cheekily, but pleasingly, and thankfully, as it does allow for a succinct, but nonetheless engaging, presentation of works by Wagenfeld for Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke, including his 1939 apple grater, various glasses and vases and, and as the law dictates, his Kubus stacking food storage system, a nice compeer to Dell’s stacking plastic, not only from principle but, and as we learned from the exhibition Stapeln. Ein Prinzip der Moderne at the Wilhelm Wagenfeld Haus Bremen, a system which, as with Dell’s work for Römmler, made use of the latest material and production technology to develop something new, something relevant for contemporary society.

Which is very Bauhaus.

Lamps by Christian Dell for Rondella (l) and Römmler (r) (and a Russian copy of the Römmler lamp!!), as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

Bauhaus wasn’t however only about production, be that by craft or industrial processes, but encompassed a whole raft of creative expressions and also existed, in many regards, as a mediator, communicating the contemporary creative, formal, functional et al understandings to the wider public.

Irmgard Kiepenheuer may be the only one of the nine featured protagonists not to have studied at Bauhaus, but through her Potsdam based publishing company Müller & Kiepenheuer was not only closely related to the school and its protagonists but also an important figure in that communication. Amongst Müller & Kiepenheuer’s earliest cooperations with the school was the publication of the well meant but ultimately ill-fated Neue Europaische Grafik series, a publication initiated by Gropius in 1921 with the aim of publishing folios of previously unpublished, well, new European graphics, the profits from the sales being intended to support the school. A good plan, were it not for the hyper-inflation of the early 1920s and associated economic chaos. In addition Müller & Kiepenheuer published numerous works of a modernist, avant-garde, vogue, among those presented in the Dieselkraftwerk being the 1928 work Probleme des Bauens by Fritz Block, a catalogue for the Dresden based, Modernist, gallerist Ida Bienert, the home style guide Jeztz wird ihre Wohnung eingerichtet by ex-Bauhasler, and ex-De Stijl, member Werner Graeff and the 1931 children’s novel Nickelmann erlebt Berlin by the author and progressive pedagogue Tami Oelfken.

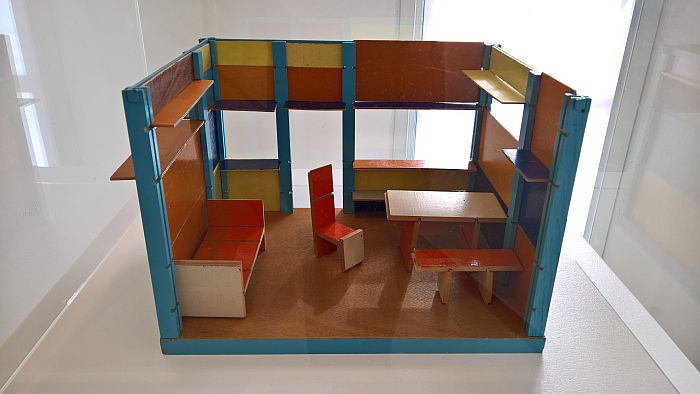

The latter being a book that may very well have been found in the Pädagogische Akademie in Frankfurt (Oder). Established in the 1920s, and as with Gildenhall in the spirit of the reform movement, and thus an institution intent on moving schooling and teaching away from the strict rules and dogmatic drills of traditional pedagogy and moving it into something altogether more open, friendly, humane, contemporary and an institution which from 1930 until its closure in 1932 counted amongst its staff Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack. A student of Lyonel Feininger at Bauhaus Weimar, Hirschfeld-Mack subsequently taught at the influential Freie Schulgemeinde Wickersdorf and the aforementioned Staatliche Bauhochschule Weimar before moving east to Frankfurt. A central aspect of Hirschfeld-Mack’s teaching and wider work was colour theory, an interest that began at Bauhaus, where in 1922/23 he taught an extra-curricular colour course, and which saw him develop both a colour spinning top to explain how different colours combine and an educational dolls house, essentially a construction based around prefabricated slats and objects in different colours which children could arrange and rearrange and thus get a feel for colour and form. And a house presented in Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg not only as a 1924 original model, but also a hands-on-try-yourself version, for children young and old alike to play and experiment with. Similarly the copies of the spinning top. And objects which thus continue Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack’s teaching processes and in doing so allow for a practical understanding of what they were and what they hoped to achieve.

Dolls House by Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

As regular readers will be very well aware, we often note from exhibitions where ceramics and associated small/fragile objects are presented that the exhibition design features “lots of small objects in glass vitrines”, a presentation format we invariably castigate as being not ideal, never ideal, but then it is a display of ceramics in a museum, ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg deliciously demonstrates there is an alternative with its creation for the presentation of objects by Heymann-Loebenstein, Bogler & Burri of, in effect, small display windows, a scenography as if one is looking through the window of a small local pottery, the wares laid out for your delectation and contemplation on makeshift tables, all you need to do is enter and purchase. Yes there is something romanticised, intensely-faux, about it, and therefore means the presentation format stands at odds with the more honest, if every bit as imaginative, works on show, but the juxtaposition works effortlessly, not least, arguably because, it is so obviously a staged presentation, and one you’re more than happy to play along with because it resonates with you, is how one, at least how one imagines how one, naturally views ceramics. And, yes, if that all sounds very theatrical the exhibition design was realised by Hans-Holger Schmidt, Stage and Costume Designer at the Staatstheater Cottbus. And thus also neatly underscoring that museums needn’t only commission architects and professional exhibition designers for their scenographies, they can, should, think outside the box, across genres. Which is very Bauhaus.

Equally pleasing is the fact that much as the tables of the faux-potteries rest upon local bricks, so the furniture from Eberhard Schrammen stands on Velten tiles in their glorious green; and tiles which not only grace the Dieselkraftwerk itself but were popular with architects in and around Berlin in the early decades of the 20th century, the aforementioned Bauhaus predecessor Peter Behrens using them in several of his projects, including the U-Bahn station at Moritzplatz, and thus making them very much a component of Modernism. From Brandenburg.

A bijou exhibition yet one with a very pleasing, scope and diversity, if one disappointingly only in German, Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg doesn’t, can’t, tell the compete stories of its protagonists, their works and relevance/legacy, but provides more than enough input and impetus to encourage you to do that research yourself, and also very neatly illuminates and focuses attention on the networks and connections emanating from Bauhaus and that Bauhaus was but part of something larger, or as Walter Gropius wrote to Else Mögelin “I find the path you have taken most agreeable. Because the mushroom must disseminate seeds, so that many small eruptive plants can develop”1: something very neatly echoed in Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg, and which reminds us that there are invariably a lot more small eruptive plants to be discovered. All we have to do is go look for them.

- Catalogue and works from Steingutfabriken Velten-Vordamm, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Folio pages from Neue Europaische Grafik printed by Müller & Kiepenheuer, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Works by Wilhelm Wagenfeld for Vereinigte Lausitzer Glaswerke Weißwasser, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- A toy donkey by Else Mögelin , as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Works by Werner Burri for Steingutfabriken Velten-Vordamm, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Furniture by Eberhard Schrammen, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Works by Margarete Heymann-Loebenstein for Haël-Werkstätten, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Works by Else Mögelin, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Probleme des Bauens by Fritz Block printed by Müller & Kiepenheuer, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

Im Hinterland der Moderne

A particularly pleasing aspect of Unknown Modernism is that the BLMK, in association with the Institute für Neue Idustriekultur INIK GmbH, have produced a travel book taking visitors on tours through 30 Modernist sites contained, more or less contained, within a triangle formed by Cottbus and Frankfurt (Oder) in Germany and Zielona Góra in Poland, whereby the curators are most keen to point out that there are a lot more than 30 Modernist sites within that triangle, but in order to keep the book within the reasonable and practical, 30 were selected; and a work which not only introduces many little/un known Modernist era works, including those by the likes of Bruno Taut, Max Taut, Leberecht Migge or Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, but actively encourages you to visit them. And thereby not only discover unknown Modernism but the unknown German and Polish Lausitz. Of which there is, it’s fair to say, an awful lot. And that despite it being an easy day trip from Berlin.

The book is represented in Cottbus in the museum shop, obviously, but for all by Im Hinterland der Moderne a presentation of photos commissioned for the book by 10 photographers, including Lars Wiedemann, Anne Heinlein or Margret Hoppe, the latter who first made a name for herself with her photos of works by that, short term, ex-Brandeburger Le Corbusier, and of architectural projects such as, the Siedlung Rosa-Luxembourg-Straße in Guben by Willi Ludewig, the sanatorium in Trzebiechów by Max Schündler, with interior design by Henry van der Velde, the Erich Kästner-Grundschule in Frankfurt (Oder) by Josef Gesing, and, logically, the Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus…….

……….Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus?

Oh stop it…..

- Im Hinterland der Moderne, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Im Hinterland der Moderne, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Im Hinterland der Moderne, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild

Modernism, clearly, isn’t/wasn’t just design and architecture but an expression of the social, cultural, political, economic, technical et al realities of the period across creative genres, including, logically, art. Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild [Pictures of the City/The City in Pictures] presents a collection of works which explore various aspects of the evolutions, transformations, tensions of the period, for all the social and economic evolutions, transformations, tensions, including critical reflections on and expressions of, and amongst other themes, industrialisation, the increasing gulf between rich and poor, the liberation from previously accepted social and political norms, evolving understandings of sexual emancipation, sexual identity or gender roles, the latter including, amongst other representations, Richard Birnstengel’s 1927 work Laborantin, a work which demonstrates that whereas in 1989 the Guerrilla Girls collective were asking if women had to be naked to get into art galleries, in 1927 an understanding of chemistry or pharmacology sufficed. And a work that very nicely resists and rebuffs the sort of attitudes embodied by an Oskar “where there is wool, there is a woman” Schlemmer.

And evolutions, transformations and tensions reflected and expressed through new artistic understandings, through new media, new vocabularies, new figurative forms, new aesthetics, and for all though a move away from the conventional, traditional, formal understandings and artistic practices, traditional understandings and practices which, arguably would have been unable to so fulsomely reflect and express the new, evolving, society. Certainly not in all its vibrancy and variety.

Presenting works by some 50 artists including the likes of Albert Renger Patzsch, Hans Finsler, Tina Bauer-Pezellen, Frans Masereel, Augustin Tschinkel or Gerd Arntz, the latter two in particular catching our attention with their pictogram work which aside from being the most engaging and alluring of works, works which present very playful, almost naive yet sharply focussed critique on the predominant economic and political systems of the period, also document the way the Années folles famously ceded to something altogether darker; albeit documentations in a manner that clearly indicate that amongst the hopelessness and desperation, there was also an unignorable and irresistible resistance. Which is a very important message.

As is the fact that while amongst the 50-ish artists one finds numerous Bauhäusler including, and amongst many, many others, Hajo Rose, Gyula Pap, Ré Soupault, Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, Irena Blühová or Marianne Brandt, the works aren’t presented as being “Bauhaus”, but rather as part of the wider discussion and discourse in which they stand, and which through the effortless, easy, manner they co-exist alongside works by non-Bauhäusler contemporaries very neatly and satisfyingly underscores that Bauhaus was simply a component of a wider inter-War Modernism, if one through which many paths, known and unknown, ran and run.

Paths which as they run through the Dieselkraftwerk Cottbus, and to paraphrase Walter Gropius, are “most agreeable”, and which allow one to become much better acquainted with both the previously unknown, and that which you thought you knew……

Unknown Modernism runs at the Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Dieselkraftwerk, Uferstraße/Am Amtsteich 15, 03046 Cottbus until Sunday January 12th

And at both Rathaushalle, Marktplatz 1 & Packhof, Carl-Philipp-Emanuel-Bach-Straße 11, 15230 Frankfurt (Oder) until Sunday January 12th

Full details including information on the accompanying fringe programmes can be found (German only) at www.blmk.de

1. “Den Weg, den Sie beschritten haben, ist mir ausgesprochen sympathisch, Denn der Mutterpilz muß Samen ausstreuen, damit viele kleine eruptive Pflanzen entstehen können” Quoted in exhibition, original in a letter from Gropius to Mögelin 09.05.1924

- Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Two takes on womanhood, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

- Works by Gerd Arntz, as seen at Unknown Modernism, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus

Tagged with: Bauhaus, Bild der Stadt/Stadt im Bild, Brandenburg, Brandenburgisches Landesmuseum für moderne Kunst, Cottbus, Das Bauhaus in Brandenburg, Dieselkraftwerk, Frankfurt, Im Hinterland der Moderne, Unknown Modernism