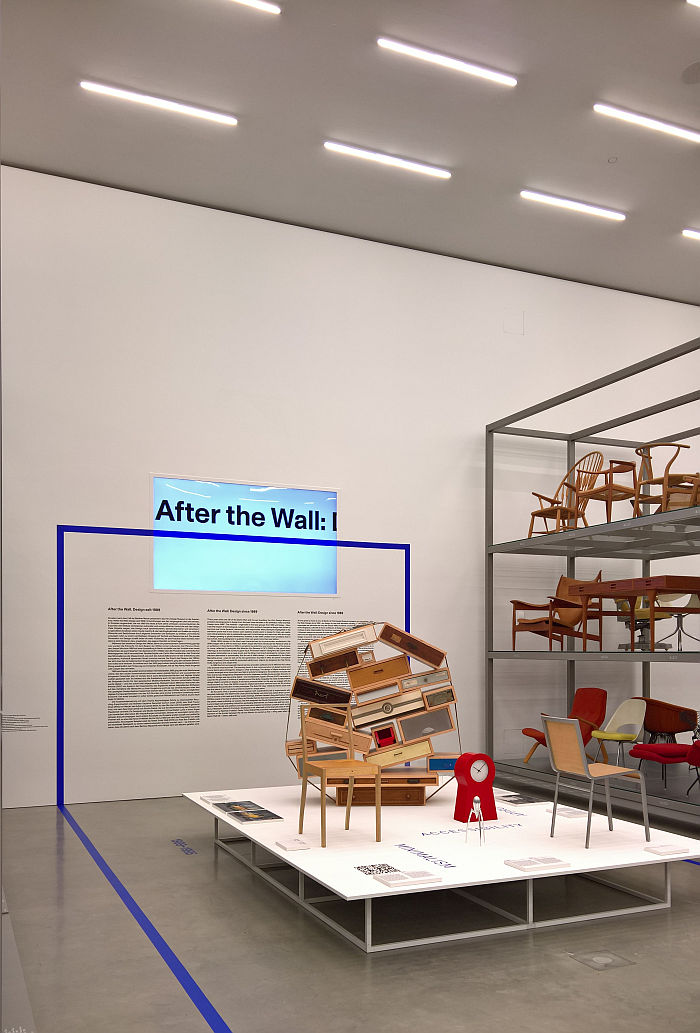

After the Wall. Design since 1989 @ the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Weil am Rhein

Birthday’s are not only an occasion for celebration, but also for reflection on the year past, and on those milestone birthdays, for all the decadal birthdays, to reflect wider on the lives you’ve lived and the experiences you’ve enjoyed/endured, reflect on what you’ve gained, what you’ve lost, in those decades past.

So, or similar, the Vitra Design Museum, who celebrate their 30th birthday in November 2019 and are marking the occasion with reflections, when not necessarily on their own three decades, but the past three decades in design…….

Established, essentially, as an archive and refugium for, then, Vitra CEO Rolf Fehlbaum’s furniture collection, not least an extensive collection of Thonet bentwood furniture he had recently acquired, the Vitra Design Museum initially staged sporadic exhibitions, beginning in 1990 with an exhibition devoted to the, (still) relatively unknown (and unfairly so) furniture designer Erich Dieckmann, followed by shows on, for example, Czechoslovakian cubism or the history of the cantilever chair, before in 1993 realising one of their most important exhibitions: Citizen Office, with, as the subtitle elucidates, its, Ideas and Notes Concerning a New Office World, and an exhibition which not only saw the Vitra Design Museum become a place of experimentation and abstract research as much as place of display and education, but also influenced the direction of Vitra, an influence that, as we opined from Vitra Work at Orgatec 2018, is still very much felt today.

With the 1997 exhibition Alla Castiglioni and 1997/98’s The Work of Charles & Ray Eames, the Vitra Design Museum began staging more regular exhibitions, initiated, more or less, its now familiar rhythm of two exhibitions a year; a rhythm which over the intervening two decades has rolled out both thematic exhibitions such as, and amongst many others, Kid Size: The Material World of Childhood, The Essence of Things. Design and the Art of Reduction, Lightopia or Pop Art Design, and also numerous solo shows presenting designers and architects such as Joe Colombo, Isamu Noguchi, Balkrishna Doshi, Gerrit Rietveld, Louis Kahn and a great many more. Or at least a great many more male designers and architects, the Vitra Design Museum’s first solo exhibition devoted to a female creative is still (very much) awaited.

Housed since November 1989 in a building by the Canadian architect Frank Gehry, in 2016 the Vitra Design Museum expanded its estate with the Schaudepot, a work by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron and which in addition to providing for a permanent presentation of, or at least a small part of, the Vitra Design Museum’s collection also stages regular thematic exhibitions based on works in that collection.

Exhibitions such as After the Wall. Design since 1989.

For Public Enemy 1989 may have been “another summer”, for a great many others it was anything but “another” summer. Or indeed “another” spring, winter or autumn. Quite aside from the fall of the Berlin Wall, the drawing of the Iron Curtain along its full length and the end of the military dictatorships in Chile and Paraguay, 1989 also saw the beginnings of the end of Apartheid in South Africa and, very, very nearly, the beginnings of the end of China’s Communist Party’s solitary, singular, grasp of power.

In addition, and as we noted from the exhibition 1989 – Culture and Politics at the National Museum Stockholm, 1989 was also an important year in terms of cultural expressions, or perhaps more accurately put, 1989 stands as a very sharply focussed, macro, snapshot of developing contemporary understandings of cultural expressions, such things being as they are fluid, and fixed points rarely definable; however, it is, we’d argue, fair to say that the late 1980s marked the end of, certainly provided a clear indication that end was neigh for, Postmodernism and witnessed the first blooming of new reflections on creative, aesthetic expression. Changes inarguably associated with and related to the evolving political situations of the late 1980s, but also, to evolving social understandings and economic realities, as we all developing technology. And that just as 1989 can, if somewhat over simplistically, be understood as a “watershed” year politically, equally one can justifiably, if somewhat over simplistically, understand 1989 as a “watershed” year culturally. It is certainly a valid starting point for any exploration of and reflections on contemporary design. Not least when it coincides with your birthday. Because what are birthdays, if not moments of reflection.

To this end After the Wall presents a narrative developed over 6 snapshots, wide-angle snapshots, each representing a 5 year period and reflecting on themes, concepts, understandings of design that while clearly identifiable with that semi-decade, aren’t unique to that semi-decade; however, which when viewed together presents a very smooth, flowing and cohesive panorama.

Opening with 1989 – 1995, which, yes, is 6 years, After the Wall begins by underscoring the impulses from 1980s Postmodernism; both directly in the case of Tejo Remy and his chest of drawers bricolage You Can’t Lay Down Your Memory as a reflection of Postmodernism’s appropriation, and more indirectly in the form of Jasper Morrison’s minimalist Plywood Chair, a work which, and as we noted from Stockholm, was realised in the, anything but minimalist, wilds, of 1988 West Berlin, but clearly implies a change is coming. Arguably is longing, begging, pleading for that change.

A change discussed in the decade through to 2005 via a, if you so will, refining and evolution of Postmodernism, a refining and evolution of formal aesthetic expressions, of understandings of the role of the designer, of our relationship to those objects which surround us, of the form/function relationship, and also sees the development of new positions enabled by new technology, new materials and enforced by evolving social understandings; developments discussed in After the Wall by objects such as the May day lamp by Konstantin Grcic for Flos, the first Emojis by Shigetaka Kurita and his team, the Honey-pop chair by Tokujin Yoshioka, the Harumaki chair by Fernando and Humberto Campana or Frakta by Marianne and Knut Hagberg for IKEA.

Frakta?

It’s a blue bag. No, we didn’t know it had a name either. But did and do understand IKEA, and as also presented in Nordic Design. The Response to the Bauhaus at the Bröhan Museum Berlin, as an understanding of a democratisation of design.

Democratisation of a different kind arises in 2006-2010: the iPhone and Instagram, standing representative for smartphones and social media for, arguably, two of the biggest and most fundamental developments since 1989, and two which have left their mark on design, and society, both directly and indirectly…..

…..but not exclusively, further influences on and expressions of design and its social, cultural, technological, et al relationships are discussed up to, and beyond?, 2019 via themes such as Maker Culture, Peer Production, Social Justice, and also a subject that as we noted from 1989 – Culture and Politics was present in 1989, loudly ringing a very large bell, but which was widely ignored, and which today is a major issue in design, and society: the environment.

And social and cultural developments and environmental understandings explored through projects such as Studio Swine’s Sea Chair, the Teeter Totter Wall project by Studio Rael San Fratello, the Jamil chair by Bethlehem based label Local Industries, or the Union Chair by Burg Giebichenstein Halle graduate Hauke Odendahl. The latter being a new project to us, and one that, as anyone familiar with the peculiarities of these dispatches will understand, particularly caught our attention. Based around 28 wooden slats, one for each of the 28 EU member states and held together by the rules, history, geography and inter-dependencies of its butterfly screws, the user is free to decide on the exact form of the chair, thus deliciously mirroring the flexibility inherent within the EU, but also accentuating that that flexibility must never be allowed to endanger the stability. In which context come March 21st 2019, October 31st 2019, January 31st 2020 one slat will be removed, and then…..? Or maybe it won’t, who knows……

Immensely satisfying and enjoyable as Union Chair is and was, we couldn’t help reflecting that by 2019 the EU should really have developed into something much more resemblant of the stable, untroubled, molten mass of colour and diversity that is Jerszy Seymour’s Living Systems chair, which stands directly beside the Union Chair. But were also very thankful it isn’t the rigid, unyielding networks and nodes of Marcel Wanders’ Knotted Chair, an object to be found a couple of shelves higher….

Union Chair by Hauke Odendahl (and in the background Jerszy Seymour’s Living Systems chair), as seen at After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot

Taking the viewer on a sprightly, though not overly hasty, tour over the past three decades, After the Wall provides for a coherent, easily readable, if by necessity abbreviated, exploration of developments in design understandings since 1989, and where, quite aside from the chance to get up close and personal with objects one doesn’t always get a chance to, and to query when Flos and Konstantin Grcic will finally get round to a cable-free, rechargeable, May day lamp, also allows for some very nice, and thought provoking juxtapositions: 1995-2000, for example, presenting both Mass Consumption and Democratisation, and thus tickles the inkling that since 1989 the latter has been understood as being exactly equal to the former, but is it? Really? Or is that just a commercial understanding of democratisation rather than a design understanding? Did part of Postmodenism’s message get lost in the refinings and evolutions of the early 1990s?

Similarly 2006-2010, presents the Smartphone Generation alongside Open Source Design, a proximity that deliciously underscores that where we currently are isn’t where we, logically, should be, that the combination of the global freedom of the internet and altruistic, uncompelled, social cooperation should, must, be a force for the aforementioned democratisation. Of design and society. But we, in our infinite wisdom, choose to concentrate on our smartphones rather than our social fabric. And look where that got us. Thoughts which, for us, tend to reconfirm our understanding from 1989 – Culture and Politics that history won’t look kindly on us for the way we’ve messed up the rearing of that other child of 1989: the world wide web.

Quite aside from the showcase itself, one of the real highlights of After the Wall is the opportunity one has to leave the presentation and examine the positions and objects presented in a wider context. Or put another way, normally in a design exhibition you only have the objects in front of you, in the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot you are surrounded by 100+ years of (furniture) design history, and which means that you can explore the positions and objects outwith the presentation per se. And in doing so one approaches a better understanding of the continuum that is design, that design is an expression that is continually updating and evolving. Jasper Morrison’s Plywood Chair, for example, may be a minimal object, but any less minimal than, for example, Michael Thonet’s 19th century bentwood chairs? In how far does the mass consumption of the early 1990s differ from that of the 1950s as characterised by Charles and Ray Eames fibreglass chairs? Is upcycling not just a further, rational, development of the Bricolages and Readymades that one can experience both in the Schaudepot and in their original 1920s understandings in the main museum’s exhibition Objects of Desire. Surrealism and Design 1924 – Today? And while one can speak of Post-Plastic, one must remember that the use of plastic was once pitched as being Post-Wood, or as Anna Castelli Ferrieri once opined “plastic is the only ecological material that exists today. You should leave the wood in the forests. We should not work with anything that can come to an end, can run out.”1 A belief in the power and probity of plastics echoed by her contemporary Gaetano Pesce’s installation for the MoMA New York’s 1972 exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape and his claim that, in context of an archaeological dig in the year 3000, “all the structures in wood, ABS plastic, melamine, polyurethane, etc., have been irreparably lost or damaged by heat and humidity.”2

Viewing projects such as Marjan van Aubel & James Shaw’s Well Proven Chair, Marleen Kaptein Recycled Carbon Chair, the Algae Lab project by Studio Klarenbeek & Dros or Studio Swine’s Sea Chair in direct proximity to a whole host of works in a myriad of plastics, forces considerations not only on how the discussion around plastics has altered since the 1960s, but also on in how far plastic is the problem, and in how far we are the problem? Does plastic not offer advantages in certain situations? Are there ways of using the properties and possibilities of plastics better than those we’ve chosen? Were the likes of an Anna Castelli Ferrieri or a Gaetano Pesce not fully justified in their unbridled enthusiasm for plastics, but the subsequent development went a little off-kilter? Could our development and use of new materials and new production processes not go equally off-kilter?

And thus leads into further, wider, thoughts on materials, production, consumption, objects, thoughts supported and broadened by the 100+ years of (furniture) design history that surrounds you, and which underscores the importance of properly studying previous understandings of design and learning from them, for as viewing After the Wall very neatly and succinctly confirms, in terms of design that which is new is invariably just a further development of that which we once had, that the life we have today is just a further development of the life we once had, one enabled by evolving technology and informed by evolving social/cultural/et al understandings, but influenced by and rooted in the lives you’ve lived, the experiences you’ve enjoyed/endured, what you’ve gained and what you’ve lost.

You’re going to get older, that’s out of your hands, if however you also get wiser is very much in your hands. And so don’t just celebrate birthdays, but use them to reflect…….

After the Wall. Design since 1989 runs at the Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Charles-Eames-Str. 2, 79576 Weil am Rhein until Sunday February 23rd

Full details can be found at www.design-museum.de/after-the-wall-design-since-1989

1. Florian Hufnagl (Ed.), Plastics + design, Die Neue Sammlung, Staatliches Museum für Angewandte Kunst, München, Arnoldsche Verlag, Stuttgart, 1997

2. Emilio Ambasz (Ed.), Italy: the new domestic landscape achievements and problems of Italian design, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1972

- Bucky by Marc Newson (l) & May day lamp by Konstantin Grcic (r), as seen at After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot

- Jamil by Local Industries (l) and Edie from Opendesk (r), as seen at After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot

- Sea Chair by Studio Swine (l) & Well Proven Chair by Marjan van Aubel and James Shaw (r), as seen at After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot

- Honey-pop chair by Tokujin Yoshioka (l), Harumaki chair by Fernando and Humberto Campana (m) & Solid C2 by Patrick Jouin (r), as seen at After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot

- Emil & Clara by mischer’traxler, and n the background that other conector, an iPhone, as seen at After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot

- After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Weil am Rhein

- Kreuzberg 36 Chair by Van Bo Le-Mentzel (l) & 111 Navy Chair from Emeco (r), as seen at After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot

- After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Weil am Rhein

- After the Wall. Design since 1989, Vitra Design Museum Schaudepot, Weil am Rhein

Tagged with: After the Wall. Design since 1989, Schaudepot, Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein