From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

On October 31st 1517 Martin Luther published his 95 Theses, his Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, his criticism of the contemporary Catholic church. 95 theses which fired a debate and discourse that, ultimately, led to the splitting of the, until then, all-powerful Catholic church, an event which was to have consequences far, far, beyond religious practice and power, and which was arguably one of the single most important moments in the development of European society.

According to the popular telling of (hi)story, Martin Luther published his 95 Theses by…… nailing them to the door of the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg.

Imagine if @DrMartinLuther95 had had 60 million followers on Twitter…..

With the exhibition From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, explore developments in the nature of public debate and discourse and the role of evolving media and technology in those developments.

The church as an early “pillar of truth”, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

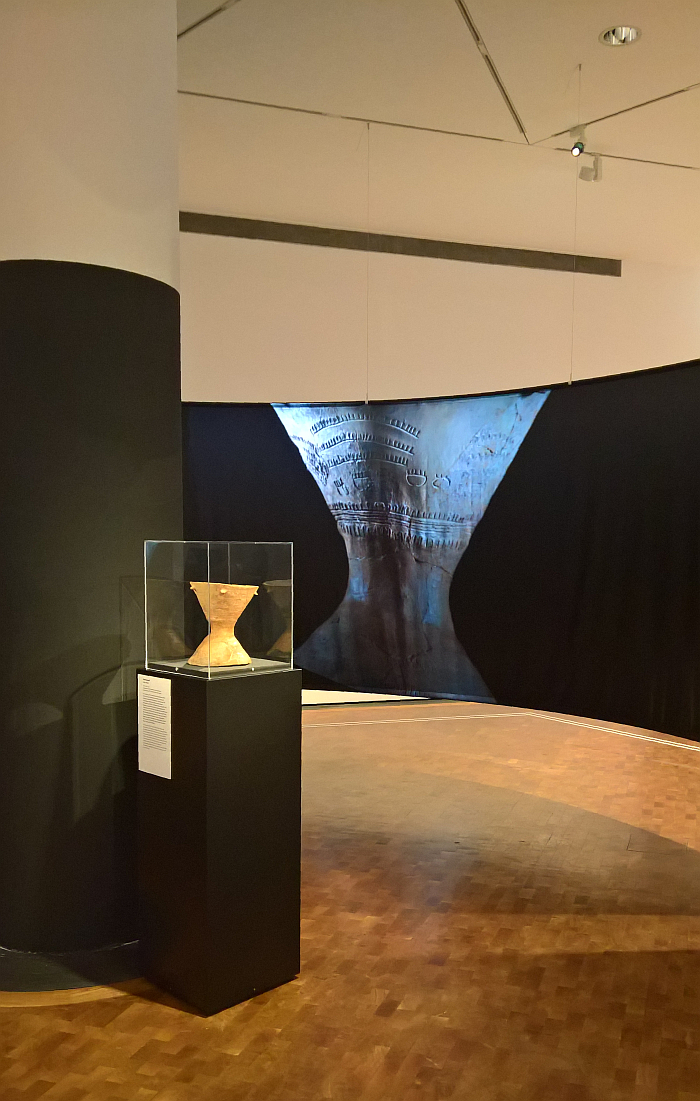

Despite the somewhat unequivocal title, From Luther to Twitter doesn’t open with Luther, but with a 5,000 year old clay drum belonging to the neolithic Salzmünder culture and discovered in Zorbau, near Leipzig, an object adorned with symbols and signs, and thus a reminder that language, certainly written language, is relatively new, that for centuries our ancestors communicated visually.

And also a reminder that the development of language, certainly language founded on a universal syntax, is/was an important prerequisite for the development of conscious thought, for the development of the ability to form causalities, relationships and arguments, and thus for both the construction of opinions and positions and reflection on the opinions and positions of others. Allowed for a culture of public debate and discourse.

A culture of public debate and discourse which although, arguably, has its origins, enjoyed its first bloom, in ancient Greece, as the opening chapter of From Luther to Twitter argues, first achieved a medial relevance, association and importance with the development of the printing press, and for all the contribution of Johannes Gutenberg to the development of mechanical printing; Gutenberg’s mid-15th century press with interchangeable letters increasing the speed at which books, pamphlets, flyers et al, could be printed and thus not only allowing for an ever more rapid distribution of opinions and ideas, but also seeing the demise of the scriptorium where for centuries scribes had laboriously copied books, documents, decrees, etc by hand.1 And thus a nice example that we shouldn’t fear job losses to new technology, it’s part of how society evolves, but much more that we should, must, question the value of that technology, what that technology is actually enabling us, what humanity gains from the change, and for all the dangers inherent in replacing those humans with that technology. But we digress……

……..and a printing press that brings us to Martin Luther.

And that while Luther may actually, genuinely, have nailed his 95 Theses to the Schlosskirche door, that would (in all probability) have been a largely symbolic act, a component of the established public debating culture in early 16th century Wittenberg; the much more important act was the subsequent printing and distribution of the Theses, and as From Luther to Twitter notes, by 1525 there were some 1,465 print editions of Luther’s Theses in circulation. And which were joined from 1520 by four books by Luther in which he expands on his criticism of the contemporary church and presents his ideas of a future church; and joined from 1522 by Luther’s translation of the bible from the ancient, unspoken, languages of the church into the contemporary, spoken, German of the church’s subjects, or at least those subjects in Luther’s corner of 16th century Europe, and which allowed for wider access to the bible, and for all access independent of the church, allowed anyone who could read to form their own interpretation and opinion of the work. And compare that to Luther’s interpretation and opinion. Enabled a wider public debate and discourse on the practices, positions and powers of the church.

And thus a body of work realised, importantly, in a relatively short period of time, which was of central importance to driving (what became) the reformation, and which very neatly underscores not only the central importance of the mechanised printing press to the reformation, and all that has subsequently developed from that schism in Catholic church, but also the relevance of new technology to public debate and discourse, that the medium may or may not be the message, but that the evolving nature of the medium is dependent on technological developments.

Relationships between media, technology and public debate and discourse charted and explored in their further evolution and development in From Luther to Twitter‘s subsequent chapters.

A 4th millennium BCE Salzmünder drum, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

From the book the exhibition’s narrative moves to the newspaper, an object which although known since the 17th century came into its own in the 19th century in conjunction with not only the development of the steam powered rotary press which allowed for mass, industrial, reproduction, but the, more or less simultaneous, development of the electric telegraph which allowed for the rapid transfer of information and opinion from far flung corners of the globe and thus increased not only the geographic scope of debate and discourse but also the breadth of public debate and discourse, the number of voices. And a burgeoning 19th century newspaper industry which, as the curators discuss, stood in close association with the development of political organisations and parties. Organisations and parties that my not necessarily exist today, but whose economic, social, cultural et al principles and ideals continue to resonate through contemporary political organisations and parties. And also stood in close association with the development of the targeted (mis)use of media for propaganda, to establish and stabilise power, a particular focus in the exhibition being Bismarck’s (mis)use of the press. And also with the development of censorship as the ruling class sought to maintain their hold on power as the masses realised the possibilities inherent in their’s.

And a political misuse of media, a political control of medial dissemination, that the NSDAP, intuitively, understood to exploit and which in radio they found the near perfect conduit. As From Luther to Twitter neatly explains, public radio in Germany began in 1923, initially, at the, then, government’s behest, as a platform for music and entertainment rather than political discourse: but which following the NSDAP’s seizure of power quickly became one of the central platforms for the dissemination of their noxious propaganda. And that not least because, and as discussed in context of Common Knowledge – Design in Times of the Information Crisis at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Dresden while books, flyers, newspapers et al require that individuals can read them, radio, radio’s message, is independent of the individuals level of literacy. And can also be delivered at a greater frequency, and indirectly while the intended recipients busy themselves with other tasks.

With the development of radio there was a certain inevitability that hearing wouldn’t be enough, that we would also want to see, and be seen.

Something that was possible from the late 1920s and which from the 1960s onward became increasingly commonplace. And collective, and that despite TV being a media (largely) enjoyed, consumed, in the privacy of one’s own home: From Luther to Twitter presenting a series of what are termed “”icons” of television history”, a series of collective TV moments, including, the 1969 moon landing, Muhammad Ali and George Foreman’s 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” and the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and also, and in context of its main focus of media and public discourse, the 1960 US Presedential election debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, one of those defining moments in the (hi)story of TV as a medium for stimulating and encouraging public debate. And a not unimportant moment in the career of Hans J. Wegner and his JH 501.

Yet for all that TV, as Marshall McLuhan opines, and From Luther to Twitter neatly illustrates meant that “the living room has become a voting booth”,2 as Gil Scott-Heron told us in 1971, The revolution will not be televised.

If not, as Scott-Heron thought, because “the revolution will be live”, “because black people will be in the street looking for a brighter day”, rather than vegetating in front of their TVs absorbing, accepting and normalising the primacy of white culture, but because, and as we understand today, the revolution will be live streamed.

Discussion on radio, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

Despite the somewhat unequivocal title, From Luther to Twitter doesn’t end with Twitter.

But the internet in general.

And a discussion undertaken in three discourses – Early Network Utopians, Digital Surveillance and Social Media – and a discussion which although very much about our contemporary digital, networked, culture, about relationships between media, technology and public discourse in context of our contemporary digital, networked, culture, is also a reminder, confirmation?, that while the path taken since the development of mechanised book printing may have been one undertaken in context of ever new technologies, from Luther to Twitter public debate and discourse has been undertaken in very similar manners, via very similar means and in context of the complicated relationship(s) between power and empowerment.

Or put another way, is a discussion undertaken in three discourses – Early Network Utopians, Digital Surveillance and Social Media.

The former represented in From Luther to Twitter by the likes of Ted Nelson’s Computer Lib/Dream Machines, the Whole Earth Catalog and The WELL, one of the first online communities, and a utopian vision, a utopian spirit, echoed in Marshall Mcluhan’s 1967 book The Medium is the Massage, one of the first works to explore the relationship between media and society, and where he represents an unquestioningly positive, irrepressible, vision of our coming electronic future. Yet as we all understand today, and as we noted from the exhibition 1989 – Culture and Politics at The National Museum Stockholm, having been given the internet, one of the most popularly understood representations of our digital, networked, age, one of the most powerful tools ever developed, a tool that brings us closer together than any media before it, “we use it to steal, to cheat, to fake, to abuse, to boast, to pervert, to misinform, to bully, to manipulate.” Yet as From Luther to Twitter helps underscore such sentiments could be applied to our utter failure to grasp the unifying and social possibilities of any of the preceding technological innovations and media, a progression of developments that have successively shrunk our world, have, as From Luther to Twitter makes very clear, been every bit as powerful as the internet, media and technology whose genesis was accompanied by utopian visions of where they could take society, but that we have invariably decided to use primarily to celebrate and extol the negative of the human being. Why? Why do we do that? And then do it again, and again, and again. Yes, there are throughout history positive examples of media use, but the negative dominate. As the cases of governments attempting to control and censor media outnumber those of governments proactively exploring how new media could support democracy.

Digital Surveillance may be something very particular to our networked digital age, but is also, as the curators argue, synonymous with the importance of privacy in the development of public discourses, for all in context of the development of opinions and positions that stand contrary to those of the ruling power; as noted above, Luther’s German bible allowed private study of the bible, one didn’t have to discuss ones views with the church but could develop them alone and in (relative) safety, a situation which was important in the move towards the reformation. Similarly despite the risk of punishment if caught, the widespread ownership of radios allowed citizens in 1930s and 40s Germany to listen to broadcasts from foreign, non-Nazi, states, while post-War many in East Germany preferentially informed themselves via Westfernsehen, West TV, rather than the East German alternatives. Apart from in Dresden, obviously, where they had no choice. Yet whereas such media could only denounce you if you were caught in the act, digital media leaves trails making it much more useful to the (authoritative) state and dangerous to the (liberally minded) individual, something underscored by the presentation of artefacts from the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, including, alongside umbrellas to protect individuals from surveillance cameras, calls to protest as printed flyers rather than digital. All very 16th century. But all very necessary.

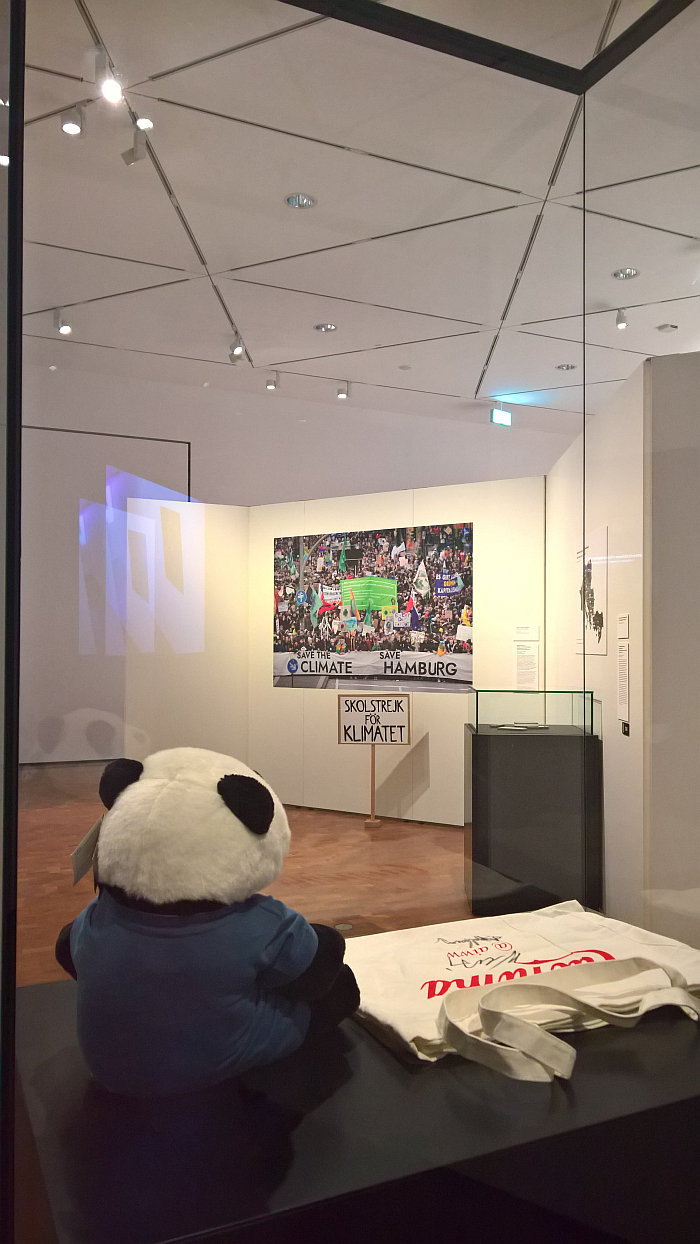

For all that Social Media is considered something very particular to our networked digital age, it is much more a digital expression of an age old phenomena; as long humans have existed we’ve formed networks, initially analogue because there was no alternative; the Salzmünder people, for example, would have organised their hunting expeditions over WhatsApp had the opportunity existed in 3200 BCE. Plus as From Luther to Twitter helps elucidate, and coming back to the Early Utopian Networks, we’ve been using media as a social tool to worship idols and defame and degenerate those of other opinions for centuries: a presentation of portraits of Luther intended to be consumed by his supporters standing juxtaposed with flyers by Luther’s supporters against the Pope and church and which present images that today would be called unchristian and subject to calls for Facebook, Twitter, Instagram et al to ban their distribution on account of their violent, hateful content. And images which no doubt would have been defended by Luther’s supporters as being “robust” arguments.

Considerations which underscore that language founded on a universal syntax may have allowed for a culture of public debate and discourse, but as species we prefer cruder methods.

And considerations which help one approach an understanding that from Luther to Twitter public debate and discourse, medial information dissemination, has always been a design subject.

Luther Portraits, a Luther bible and Luther’s followers attacks on his opponents… 16th century social media in its full spectrum, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

Initially, arguably, more a graphic subject, more about the visuals of flyers, pamphlets and newspaper layouts, etc, and that not always necessarily in terms of images as such; From Luther to Twitter presenting, for example, an edition of the Deutsche Tribüne, a newspaper associated with the liberals in the Pfalz, and whose edition from 17th July 1831 “printed” empty spaces in place of those lines that were censored, meaning the front page is essentially blank save the title and two sentences, and in doing so gloriously, and unmistakably, visualises just how much was censored. A tactic that is powerful today, and must have been particularly so then. So powerful in fact that “printing” censored gaps subsequently became illegal.

And then as media moved on from purely written to aural and visual, object design became ever more important, or as we noted from Design of the Third Reich at the Design Museum Den Bosch in context of the Volksempänger VE 301 radio developed, designed, by Walter Maria Kersting and his students at the Kölner Werkschule and made widely available by the NSDAP, “just imagine, a cheap, aesthetically pleasing, contemporary formed electronic device via which you can continuously spread, unchallenged, your falsehoods to individuals as they sit in their own homes of an evening……” In From Luther to Twitter one can explore a whole variety of Nazi era smart speakers radios, more or less aesthetically pleasing, but all developed, designed, for easing the spread of the NSDAP’s abhorrent positions and noxious propaganda, and including the Arbeitsfrontempfänger DAF 1011, a radio designed specifically for workplaces, and thus a nice example of radio’s ability to disseminate its message regardless of what the intended recipient is doing. And an absolutely fascinating object, one more reflective of an industrial toaster than a radio. If that which came out was not only unpalatable, but of no nutritional value.

And now in our contemporary digital networked age the graphic and the object design elements are of equal importance; not only do our contemporary media objects have to be formally appalling in themselves in order to be deemed useful, deemed functional, the objectification is almost as important as the object, but the visual nature of how they allow us to interact with them and with others, their graphic interface, is of equal importance. As are the emojis, memes and infographics via which we communicate.

Or perhaps better put, and now in our contemporary digital networked age the graphic and the object design elements are once again of equal importance: for what is the 4th millennium BCE Salzmünder drum if not a piece of formally considered product design whose associated signs and symbols are every bit as important as the physical object itself.

A further reminder that as species we haven’t come that far. Only the technology has.

Pandas are fans of Greta, fans of Hamburg and fans of the climate. But not fans of censorship. P2P (Panda-to-Panda) by Jacob Appelbaum and Ai Weiwei, and Fridays for Future, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

For all that From Luther to Twitter is an exhibtion about media, as an exhibition it makes particular use of one form of media in its mediation, the written word: From Luther to Twitter is an exhibition which involves a lot of reading. Which isn’t a complaint, far from it, we’re pro-reading, and in many regards the subject matter demands a preponderance of texts, and the sprightly, bilingual German/English texts help guide you through the numerous themes. Ably assisted as they do so by a varied collection of some 220 objects.

Including objects directly related to the subjects at hand, such as, and amongst others, a first edition of Luther’s German bible; Der Freischärler, a newspaper published by Louise Aston and presented as part of a discussion on female publishers during the years of the German revolution of 1848/49; or an E-Scooter as an example of digital surveillance, and which reminds us all of Florian Mehnert’s comments in context of his Freiheit 2.0 Stuttgart project that in terms of autonomous cars the manufacturers aren’t keen on discussing data protections issues as it “could also damage business models they may be planning to introduce”. Their interest might not be getting you from A to B, but what they can harvest from you during that journey. And thus the importance of always considering the dangers inherent in replacing those humans with that technology. And now we’re not digressing.

But also works of art which present the myriad subjects in more abstract connotations and thus allow for more abstracted, differentiated, considerations, art works including Kurt Weinhold’s 1929 painting Mann mit Radio (Homo Sapiens) depicting a naked man alone in his naked room, but with radio, and thus, so the implication, even more naked and alone; Eichmann, Fleischmann, Neckermann by Harry Walter in which a 1960s television cabinet stands proxy for both the complexity of our relationships with furniture and also the cultural significance of television entering the private home in 1960s Germany; and also, in many regards, the destroyed logicboard from Edward Snowden’s laptop, an object that not only is itself no longer functional, but whose destruction at the best of the British security services served no function, the information was long since disseminated. And was thus an act as meaningful as ripping up Luther’s Wittenberg Theses notice in 1527 would have been. Not that we believe GCHQ would have understood the art in the act.

And a mix of objects and text which allows for a very informative, instructive, and thought provoking tour through the history of the ever developing and evolving relationship between media, technology and public discourse.

If there is/was a weak point for us it was the presentation of the internet. A presentation which doesn’t feel complete. It’s an exhibition space with a lot of empty space, a lot of blank walls greet you as you wander through it. Which isn’t a great look for an exhibition space. But which may be deliberate, you might be supposed to feel as if you are in the infinite depths of a secret NSA facility, the disorientating basement of an unrecorded prison in an authoritative state, or in a particularly dystopian Dilbert cartoon. But it also feels very empty. Feels as if some of the exhibits didn’t make it. But the space couldn’t be reduced. And so is, empty. And thus a space which while it doesn’t detract from your reflections and considerations on the topics at hand, is a bit of a downer in terms of the atmosphere of the exhibition. Even if you prefer the more dystopian Dilbert cartoons.

Much more pleasing is the way the relevance and importance of the five media in relationship to public debate and discourse are presented, explored and discussed in context of when they first achieved a prominence: the printing press, newspapers, radio or television aren’t discussed as contemporary media. Although they all very much are. You are left to consider them in their contemporary manifestations for yourselves, left to build your own bridge from then till now.

And which brings us back to the question, what if @DrMartinLuther95 had had 60 million followers on Twitter rather than a bag of nails and a hammer………?

Early Network Utopians, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

It might not have helped him.

On the one hand you’d have to know how many followers @PapamLeoX had, and how many followers his followers had in relation to the followers of @DrMartinLuther95’s followers. And on the other consider that Leo X’s family, the Medici of Florence, were important medieval influencers, active and successful across a wide range of platforms. And with the connections and money to not only buy other influencers, and hire companies such as Cambridge Analytica, but to develop bots and hostile networks of fake accounts and troll factories. Not that we’re saying they would have. But they did have considerable interests to protect.

And would Luther be able to find a TV station, a radio station, a newspaper today that would be open to debating and discussing the content of his Theses? The majority of conservative orientated media would, arguably, take the church’s side, see his Theses as an attack on the traditions of European, Occident, culture; more left wing media would, arguably, ignore the Theses and use their existence to argue in favour of abolishing religion; and any public service media bound to laws of impartiality would have debates in which left and right would seek to establish the primacy of their cultural viewpoint rather than actually discussing the Theses and the contemporary church.

Or, put another way, in our contemporary medial environment, a Martin Luther might just as well nail his Theses to the door of a church in Sachsen-Anhalt…..

Considerations which, however frivolous, help underscore that the path from Luther to Twitter has been one of augmentation of media rather than replacement, that new technologies have added to the medial possibilities rather than replaced them; and considerations which also help underscore that evolving media and developing technology has through increasing the channels, means and forms of public debate and discourse also increased the complexity of that public debate and discourse. The background noise has increased exponentially. Not least through the cacophony of “everyone banging their own damn drum”.

However, and as From Luther to Twitter also helps confirm, open, free and responsive public debate and discourse is important, the direction in which public debate and discourse flows influences not just our cultures and societies but future cultures and societies. And thus the importance of us all considering in detail how contemporary public debate and discourse occurs; not just the media and technology via which contemporary debate and discourse occurs, but for all the language in which it occurs, of us all better understanding that we have languages founded on a universal syntax which can be more powerful than signs and symbols, languages which can allow for public debate and discussion at more meaningful, sustainable, levels than the symbolic can ever achieve. And that understanding such, of us all considering in detail how contemporary public debate and discourse occurs, is important, not least because it might help us stop repeating some of the mistakes of previous generations.

And as From Luther to Twitter helps us all better understand, as a species we’re good at repeating mistakes, and have a lot to learn……

From Luther to Twitter runs at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Pei-Bau, Hinter dem Gießhaus 3, 10117 Berlin until Sunday April 11th

Full details can be found at www.dhm.de/from-luther-to-twitter

And as ever in these times, if you are planning visiting any exhibition please familiarise yourself in advance with the current ticketing, entry, safety, hygiene, cloakroom, etc rules and systems. And during your visit please stay safe, stay responsible, and above all, stay curious……..

- Discussion on 19th century newspapers, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

- , as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

- A Volksempfänger VE 301G (r) and a Telefunken Super “Zeesen” T 875 GWK (l), as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

- A discussion on television, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

- Objects frompro-democracy demonstrators in Hong Kong and facial recognition in China, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

- From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

- Eichmann, Fleischmann, Neckermann by Harry Walter. And a Donald Trump Twitter wall, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

- A discussion on Digital Surveilliance, as seen at From Luther to Twitter. Media and the Public Sphere Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

1. Digressing ever so slightly, but there is a page on show from the Golden Gospels of Henry III from ca. 1043 which depicts two scribes at work in a scriptorium at lecterns featuring turned but clearly purely decorative, clearly static, supporting legs, which may be a reflection of the romantic convention, or could be interpreted as supporting our dark, distressing, thoughts that La Situla del vescovo Gotofredo might not be be 10th, that the heigh-adjustable lectern wasn’t known in 10th century Milan.

2.Marshall McLuhan & Quentin Fiore, The Medium is the Massage, Penguin Books 2008

Tagged with: Berlin, Deutsches Historisches Museum, From Luther to Twitter, Media and the Public Sphere