The Grassimesse smow-Designpreis 1923: A Fantasy Shortlist

The 2023 edition of the Grassimesse Leipzig will see the inaugural awarding of the €2,500 smow-Designpreis. The first dedicated design prize in the institution’s long (hi)story. Entries are were open until Friday May 12th.

But what if that first Grassimesse smow-Designpreis had been awarded not in 2023, but 1923?

Who might have won?

Who would the 1923 Grassimesse jury have selected from the many possible candidates?

????

A smow Blog fantasy final four…….

Back in 1923 the Grassimesse1 was still, mirroring the Leipzig Messe it sought to be a high-quality alternative to, a biannual event, featuring in 1923 a spring edition in early March and an autumn edition in the first week of September. Two editions which although featuring similar line-ups weren’t exactly the same, a great many institutions, organisations and individuals only featuring in one or the other.

And a March 1923 line up of which Kunst und Handwerk, the official organ of the Bayerischer Kunstgewerbeverein, an institution who were, more or less, ever-presents at the pre-War Grassimessen, opined that, despite the unquestioned high-quality on show, despite the presented works demonstrating and adding “value from a formal, taste and technical point of view”, despite all that, “due, perhaps, to a one-sided jury, there is a certain degree of paternalism, something which should not appear at trade fairs”.2

It certainly should not!!! The jury should decide alone on the basis of objective assessments of the quality of the work, not subjectively defining and dictating which positions and approaches and materials and expressions and form languages are deemed somehow correct and worthy of being presented, and sold, to the public. To do such is not only to deny us all the right to contribute to prevailing discourses on our objects of daily use, but is to deny our objects of daily use their natural progression and evolution in context of ever changing realities. Which is a terrible thing to do!!!

And while we don’t know who that jury were, or indeed in how far Kunst und Handwerk‘s criticisms are valid, or if they are but a reflection of the Bayerischer Kunstgewerbeverein’s position in the debate that was boiling over in the early 1920s concerning the formal expression, production methods, materials et al of our objects of daily use as industry increasingly challenged the supremacy of craft and artisans; what we do know is that the 2023 jury won’t engage in any one-sided paternalism. The likes of, and amongst others, Kai Lobjakas, Stephan Schulz, Sabine Epple or Axel Kufus who compose the 2023 jury will, we’re certain, very much approach their task in an open, independent, curious, objective manner and thereby allow the “maximum latitude in terms of style”3 at the 2023 Grassimesse Kunst und Handwerk demanded in 1923.

And a 2023 jury that in contrast to their colleagues from 1923 will also be responsible for choosing the winner of the €2,500 Grassimesse smow-Designpreis.

But who might that 1923 jury have chosen had the smow-Designpreis, or indeed had smow, been around in 1923?

From this distance it is impossible to say, not least because we don’t have access to all the objects that were presented in 1923; however, based on a purely subjective assessment of the participants it wouldn’t surprise us if the 1923 Grassimesse smow-Designpreis winner had been one of the following…….

Lilly Reich:

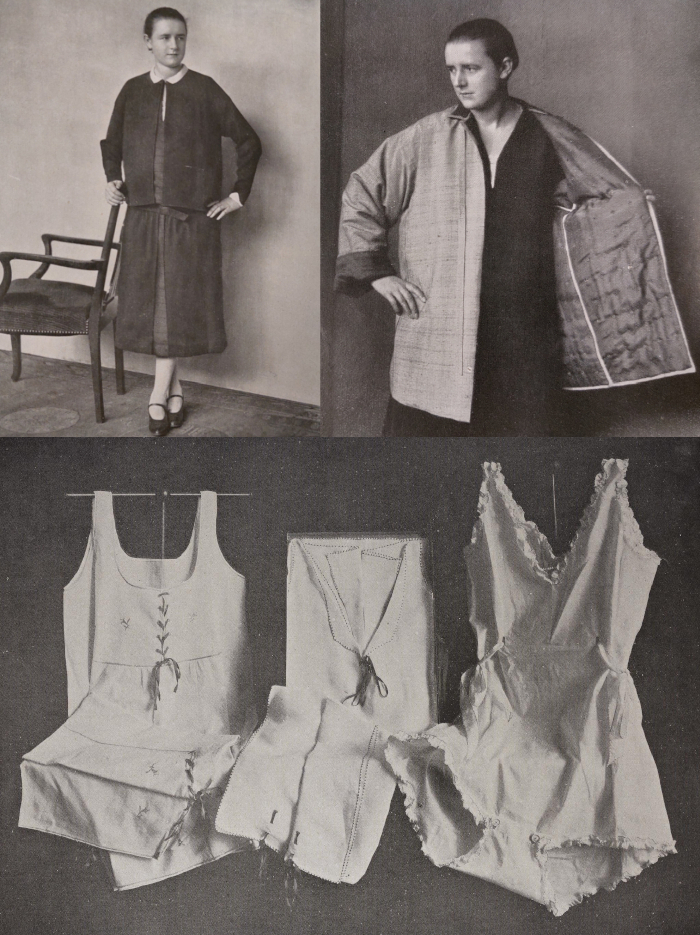

For all that Lilly Reich is popularly known today for her post-1924 collaborations with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, before meeting Mies Reich had enjoyed a long, successful, diverse career. A career that featured, for example, interior design, furniture design and shop window design, that so oft today undervalued early 20th century activity, but for all a career primarily focussed on, and regardless of what the New York Museum of Modern Art may tell you otherwise, exhibtion design4; if a varied and successful career that all too often is hidden from public view by the all-enveloping shadow of Mies. Hidden by that way Reich is so unquestioningly popularly reduced to a muse and assistant to Mies… yeah, that’s how it was, yeah….. And a career that in the course of the Great War became increasingly focussed on clothing; Reich taking a leading role in the Deutsche Werkbund’s attempts in the second half of the 1910s to encourage higher standards in the German clothing industry. An initiative in which Reich not only led the Werkbund’s activities and programmes, but led by example: designing clothes that were then produced by a (sadly anonymous) Meisterin in Reich’s Berlin studio/shop. And clothes with which Lilly Reich debuted at the 1920 autumn Grassimesse, before returning for the 1923 autumn edition and remaining a permanent feature until the 1926 spring edition. And while we don’t know what Lilly Reich presented at the 1923 Grassimesse, and have only seen a few photos of her clothing designs, nowhere near enough to make any sweeping statements; what we do know is that in a 1922 article for Die Form Reich bemoaned the dependence of the German clothing industry on Paris for ideas at the expense of local ideas and materials, its dependence on exports for income at the expense of the sustainability of the industry and quality of the products produced for the domestic market. And for all bemoaned the level of plagiarism within the industry, the unquestioning acceptance of plagiarism within the industry, and the superficiality, disingenuousness, transience of much of the work produced and the ever new styles being chased and then quickly dropped in favour of the next new style – ¿sound familiar? – and which means, for Reich, “the aesthete is satisfied, the snob even more, but one has nothing but a vain outer skin”.5 ¿Sound familiar? And thus, for Reich, there existed an urgent need for a repositioning and a rethinking of the contemporary clothing industry, for new appreciations of, and forms of, clothing, “How can a path to the new form be established”, she asks, “who knows?”, she answered. For Reich however key components of that path included appreciations that clothing “are commodities, not works of art”, a greater use of Typisierung, standardisation, that other great early 20th century theme, a greater connection to and with clothing of the past and movement forward by evolution not ever more short-lived revolutions. And through a greater reliance on craft and handwork, not however from any “sentimental reasons”6, but because of that which craft and handwork can bring above and beyond that which machines offered, a very William Morris position, albeit in same same but different political, technological, economic et al contexts. And positions an article in the February 1926 edition of Neue Frauenkleidung und Frauenkultur by Else Hoffman7 tends to imply Reich very much practised; Hoffman praising Reich’s work, Reich’s clothing, and for all Reich’s positions to form and character and craft and art and materials et al in the highest terms, and ending with the opinion that “all in all, Lilly Reich’s work reveals the revelation of a thoroughly cultivated, serious and carefully trained artistic personality”.8 As we are sure the collection she presented at the autumn 1923 Grassimesse would also have done. A collection that wouldn’t have been just clothes, but would have been an expression of Lilly Reich’s position on clothing in 1923, would have been an expression of Lilly Reich’s ideas for the way forward in 1923, would have been Lilly Reich’s carefully considered and diligently developed contribution to the contemporary discourse.

But would they have been good enough to win the 1923 smow-Designpreis?

The Grassimesse smow-Designpreis 1923 – Would Lilly Reich have won…….? (a selection of works by Lilly Reich that may or may not have been shown in 1923)

Zoo-Werkstätten für Holzbearbeitungskunst:

Wooden animals weren’t a particularly new thing in the 1920s, by that stage they had, arguably been made for thousands of years. And while wooden animals with moveable joints were also known before the 1920s, we’d argue none with the charm, grace, honesty and reduced clarity of those agile, lithe creations of Munich based Zoo-Werkstätten für Holzbearbeitungskunst. A company about whom we, currently, know only very, very little, other than they were operational throughout the 1920s, debuted at the autumn 1922 Grassimesse, participated until the spring 1924 edition, and that the jointed wooden animals were devised by one Oswald Pontius. A man about whom we also, currently, know only very, very little, other than he was by all accounts born in Oldenburg in 1889, may have briefly studied in Zürich, is more normally associated with Munich University, and that he was primarily, professionally, a chemist. But was obviously also a very keen inventor, not least in terms of toys; in 1925, for example, Pontius was awarded a patent for a new type of base construction for rocking horses, a construction principle which meant that “locomotion may be imparted by the act of rocking”.9 A genuine Rock ‘n’ Roll Horse. Which is obviously brilliant. And was also, apparently, awarded an earlier patent, although we, currently, can’t find it, for the joints of his animals, joints which, as best we understand, contain small coil springs which not only provide a little tension but protect the wood from damage through the movement; and a patent he sold to the Zoo-Werkstätten für Holzbearbeitungskunst who established production.10 By all accounts a very, very, successful production; and who didn’t just pitch the animals to children as toys but also to adults as, for example, table ornaments, notepad holders, or as educational/sketching models.11 And who, almost certainly, expanded the range. The question of who developed the wide variety of forms Zoo-Werkstätten offered is, as best we can ascertain, lost in the mists of time; however, by 1930 they were claiming a menagerie of some 260 animals12, which is a phenomenal number, and couldn’t all have been designed by Pontius. If an authorship of the individual creatures that while important, is in the current context, largely, irrelevant; in the current context the primary focus is the animals construction principle, their technical ingenuity, the quality of the work inherent in them and for all their simplicity, their unassuming self-confidence, their demand for engagement, their openness and their vitality, factors that as best we can ascertain, were maintained in each new model. Although we admittedly haven’t seen all 260. But we haven’t seen one which isn’t. In addition to the Pontius patent, which clearly served as the basis for their success, Zoo-Werkstätten received their own patent in the mid 1920s for a variation on the wooden animals: a construction set containing various body components which could be constructed, and one presumes deconstructed and reconstructed, into a variety of animals real or imaginary.13 If that kit ever reached production we no know, nor do we know if it it was available at the 1923 Grassimesse. But the jointed animals definitely were. Where they would have appealed to adults and children alike. Where they would been, arguably, one of the top sellers. Where they would have been a minor revolution. And where they would have been an absolute joy.

But would they have been good enough to win the 1923 smow-Designpreis?

The Grassimesse smow-Designpreis 1923 – Would the Zoo-Werkstätten für Holzbearbeitungskunst have won…….? (A horse and a rhino from the Zoo-Werkstätten für Holzbearbeitungskunst that may or may not have been shown in 1923, (Photos: Historisches Museum Hannover / Ulrich Pucknat via Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA))

Deutsche Werkstätten Textilgesellschaft:

Established in Dresden in 1898 the Deutsche Werkstätten, Hellerau, are and were one of the more important protagonists in the development of furniture and interior design in the 20th century: in the second half through the contributions of the likes of, for example, Rudolf Horn, Selman Selmanagić or Franz Ehrlich, in the first half through the contributions of, and amongst others, Richard Riemerschmid, Bruno Paul, Gertrud Kleinhempel or Margarete Junge. Yet for all the popular focus on furniture the Deutsche Werkstätten were also closely associated with the development of home textiles. If a lesser popularly known and appreciated role. According to Evelyn Schweynoch having been reliant on imported textiles from England in their first few years, in 1902 the Deutsche Werkstätten entered into a cooperation with the Zschopenthal, near Chemnitz, based Gottlob Wunderlich weaving mill14, a cooperation that saw the Deutsche Werkstätten offer contemporary domestic textiles designed by, and amongst others, Richard Riemerschmied, Josef Hoffmann or Margarete Junge15, who alone are a pretty stellar list for the period, if but representative of that list. And a cooperation, and a shift to creating their own furniture and domestic textiles, that proved a popular success and resulted in 1923 in the formation of the Deutsche Werkstätten Textilgesellschaft a.k.a DeWeTex, a joint project between the Deutsche Werkstätten and Gottlob Wunderlich.16 In addition to continuing the cooperation with Gottlob Wunderlich, obviously given that they were part owner, DeWeTex also began working with numerous other textile manufacturers in Sachsen including, for example, the Wurzener Teppich- und Veloursfabriken [Carpet and velor works] or the Cammann Gobelin Manufaktur, Chemnitz, on the realisation and development of their wide ranging, and continually expanding, portfolio, an indication of the strength and depth of the textile industry of the Sachsen of that day. In addition DeWeTex also continued and expanded the Deutsche Werkstätten’s cooperations with designers on the realisation and development of their portfolio; amongst the many, many names associated with DeWeTex one finds the likes of, for example, Margaret Leischner, Josef Hillerbrand, Gertrud Kleinhempel, Ruth Hildegard Geyer-Raack or Else Wenz-Viëtor17, the latter of whom had also designed furniture for the Deutsche Werkstätten before becoming primarily a textile designer and laterally a children’s book illustrator, a shift from furniture to textiles that one can understand very much as illustrative of that moment in the first decades of the 20th century when furniture design, having been essentially genderless, became a male dominion, females becoming primarily responsible for textiles and colours. A reality, a shift, a mindset, Klára Němečková opines can also be understood in the predominately female roster of DeWeTex designers.18 A roster that thus helps one site the Deutsche Werkstätten not only as a location of genuine reform and advance, but also of one retrogression. And a mindset that is still very prevalent in the contemporary furniture industry. And which must change…… But which in no way reduces the quality, be that the technical, the functional or the artistic, of the DeWeTex portfolio. DeWeTex made their debut at the 1923 autumn Grassimesse, and were to be ever-presents until the War enforced hiatus in 1941, and while we, currently, can’t be certain exactly what they presented in 1923, whose work they presented in 1923, given that DeWeTex’s presence at the 1923 autumn Grassimesse can, must, be considered as a component of the company’s launch, a PR moment on one of the biggest, most visible, highest regarded, stages for contemporary goods, one presumes, we don’t know, but one can safely presume, they would have been present with a suitably representative collection, would have shown off the best they had to offer from and through their two decades of experience in contemporary domestic textiles, would have shown those works which underscored the technical competence of their partner manufactures, would have shown those works which promoted the practical advantages of their materials, would have shown those works which highlighted the skills and artistry and contemporary thinking of their very impressive roster of designers, would have explained textile design as more than just printing pretty patterns. Would have presented those textiles that confirmed DeWeTex’s validity, singularity and importance.

But would they have been good enough to win the 1923 smow-Designpreis?

The Grassimesse smow-Designpreis 1923 – Would the Deutsche Werkstätten Textilgesellschaft have won…….? (a selection of works from Deutsche Werkstätten Textilgesellschaft that may or may not have been shown in 1923)

Emmy Roth:

Born and raised in Hattingen, near Essen, Emmy Roth’s early career is largely unknown, or perhaps more accurately, largely unverifiable on account of lost documentation. From the few snippets that we do have, she appears to have undertaken her apprenticeship with Düsseldorf based goldsmith Conrad Anton Beumers, one presumes in the early years of the 1900s; she possibly continued her training in Berlin, Paris and/or Vienna; and possibly qualified as a Meister in Berlin before establishing her own gold and silversmith atelier in Berlin Charlottenberg in, potentially, 1906/0719 at the age of just 21/22. And that as one of only very few female gold and silversmiths at that time; or as the magazine Die Kunstwelt noted in 1914, in one those very well meant but deeply patronising articles so popular in the early years of the 20th century, whereas the majority of females active in the applied arts “concern themselves preferentially and for understandable reasons, with those tasks that involve, so to speak, “female” material: weaving, embroidery, lace work and similar fine things that require careful detail work”, a state of affairs that the participant lists of the early Grassimessen tend to underscore: whereas the female representation is very high, those females are invariably present with, “weaving, embroidery, lace work and similar fine things”. However, as Die Kunstwelt continues, “in recent years the sphere of artistic materials has been expanded by women with good results” and that “some have conquered the realm of precious metals and exhibited excellent skills as jewellery artists”.20 No!!! Amazing!!! Among that new breed of women who’d evolved from “weaving, embroidery, lace work and similar fine things” to precious metals was Emmy Roth, whose work Die Kunstwelt presented, and highly praised, as in genuinely praised, across several pages with illustrations of not just examples of her jewellery but also works in carved ivory. Jewellery and carved ivory that Roth also presented at both the spring and autumn 1923 Grassimessen: it would 1925 before her silverware, that genre for which she is arguably best known today, was presented in the Grassi Museum. Silverware Roth subsequently presented, more ore less, continuously until the spring 1933 Grassimesse, the last Emmy Roth participated in, a Grassimesse staged just after the NSDAP Machtergreifung, and just before Roth fled Germany for first Paris and subsequently Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. And silverware Roth discussed in a 1926 article for Der Kunstwanderer, an article penned in context of her presentation at the spring 1926 Grassimesse, and thus a reminder that the Grassimesse has long been a highly regarded and highly visible platform from which to promote as well as to sell your work and positions, in which she discusses “Wie der moderne Siberschmied arbeitet“, How the modern silversmith works; or more accurately in which she presents her positions on objects of daily use, on the relationships between objects of daily use and users/society, and on the demands on and of contemporary silverware. And which we can thoroughly recommend21, but isn’t of direct interest here, for that is late 1920s silverware, that question if Emmy Roth would have won the smow-Designpreis at the 1925, 1926, 1927 etc Grassimessen……. Our interest here is her early 1920s jewellery and carved ivory. Jewellery and carved ivory which for all that in 1914 the decoration and motifs are and were very much the florid, historical, folkloric of so much Art Nouveau, the self-confidence of the forms is demanding that ornamentation be removed, is telling you it knows it’s superfluous, but can’t quite drop it yet, much as it would like to. Jewellery and carved ivory whose reduction and material efficiency are very much pointing a way forward, indicating what is approaching; something tending to be confirmed by a report, amongst many other contemporaneous reports, in the December 1917 edition of Dekorative Kunst of a exhibition in Berlin from which they speak of the “delicate, light objects formed by Emmi Roth out of ivory”22, and tending to be confirmed even more so in the January 1917 edition of the Deutsche Goldschmiede-Zeitung by one “Prof. L. S.” who lauds Roth’s jewellery in the highest terms, praising in particular that, for example, “everywhere rhetorical forms are avoided; agency through simple means is the first principle”, or Roth’s “fine sense for the material”, noting that he “here and there we encountered completely new motifs” and also commenting very favourably on the “architectural construction” of her objects, including the carved ivory objects, and opining that “we can still expect many new positions from the artist”.23 And thus pre-1920 jewellery and carved ivory that would, without question, have continued its journey, and become in the early 1920s, we’d argue and assume, increasingly more that which it sought to be rather than it felt it had to be in the 1910s. Would have been the expression of the age and the personality Emmy Roth bemoans contemporary jewellery (still) isn’t in her 1926 article for Der Kunstwanderer. And would have been technical and material delights.

But would they have been good enough to win the 1923 smow-Designpreis?

Which of our quartet would have gotten the nod from the 1923 jury?

Or would it have been someone else?

We don’t know. We can’t know. It’s theoretical.

What we do know, and what is very much tangible, is that entries for the 2023 smow-Designpreis are now open and so you’ve still got the chance to win the 2023 smow-Designpreis and claim your place in (hi)story. And the €2,500.

But hurry, entries close on Friday May 12th!!!

Full details, and the application portal, can be found at www.grassimesse.de

Good Luck!!!!

The Grassimesse smow-Designpreis 1923 – Would Emmy Roth have won…….? (a selection of works by Emmy Roth that may or may not have been shown in 1923)

1. As previously stated, Grassimesse is a contemporary term, and not that by which the pre-War events were known. However, in the interests of clarity and readability we use it for all editions regardless of what their actual title was.

2. Kunstgewerbe und Messen, Kunst und Handwerk, Nr. 1/2, 1923 page 10 The Nr. 1/2 refers to 1st and 2nd quarters of 1923 We couldn’t find any comment on the autumn 1923 edition, and so not sure if that was considered better.

4. as previously noted, “in context of the MoMA New York’s 1947/48 exhibition “Mies van der Rohe“, in the catalogue to which Philip C. Johnson refers to Mies’s ‘brilliant partner, Lilly Reich, who soon became his equal in this field.’ The field in question is exhibition/trade fair design, that field in which at their first cooperation in Stuttgart [in 1926] Reich was an experienced practitioner, an acknowledged expert with a decade and half of professional practice and conceptual development behind her. Mies an absolute novice with little or no experience. And Johnson only refers to the “brilliant” Reich in context of exhibition/trade fair design, all the interiors, furnishings and furniture references being the work of Mies alone. Which Mies knew was a falsification. But clearly did nothing to resolve it. The MoMA exhibition opened on September 16th 1947. Lilly Reich died on December 11th 1947. The MoMA exhibition closed on January 25th 1948. Thus at the very moment Lilly Reich passed away, Mies, Johnson and the MoMA were in the process of writing her out of history. Her corporeal and incorporeal existence ending in parallel. It’s the sort of tragic metaphor only an Émile Zola would feel confident enough to weave into a novel without turning the pathos into kitsch. And while yes, one can argue that architecture projects are rarely the work of the lead architect alone, invariably several individuals are involved, all of whom history forgets: Lilly Reich wasn’t an employee of Mies van der Rohe, but an independent designer, with her own independent studio, with whom he cooperated on an equal basis. Something he should have acknowledged. It would only have taken a couple of sentences.”

5. Lilly Reich, Moderfragen, Die Form. Monatsschrift für Gestaltende Arbeit, Vol 1, Nr 5. 1922 page 7ff

7. Possibly Else Hofmann, an Austrian art historian and journalist born in Vienna in 1893. But the “Hoffmann” definitely has a double “f” in the article

8. Else Hoffmann, Von wäsche und Kleidern, Neue Frauenkleidung und Frauenkultur, Vol. 22, Nr. 2 1926 page 39ff

9. see Deutsches Reich Patent 409458, published on 4th February 1925, in addition to numerous international patents, including, and from which the above quote comes, US patent 1,527,916 published on Feb 24th 1925.

10. If he sold the patent to a company called Zoo-Werkstätten or to individuals who subsequently formed the company Zoo-Werkstätten we no know. We suspect however that latter. But assuming the former is easier and quicker to formulate…….

11. see, for example, and amongst others, the advert Freuden ins Haus bringen die Zoo-Spiele in Jugend Nr 12 1931 page 188

12. see, for example, and amongst others, the advert in Kunst und Handwerk IV/V, 1930 page 100 By 1930 the company appear to be called Zoo-Kunst, we are unsure when the change of name took place

13. We’re aware of Swiss patent Nr. 125249 published on 2nd April 1928 and French patent Nr. 627,015 published on 24th September 1927, but currently can’t find a German patent. Very much presume however that one was granted.

14. Evelyn Schweynoch, Die Deutschen Werkstätten-Textilgesellschaft mbH in Hellerau, in Olaf Thormann [Ed.], Bauhaus Sachsen, Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig, Arnoldsche, 2019 pages 142-143

15. Kerstin Stöver, Dewetex – lichtecht und farbenfroh. Textiles aus den Detschen Werkstätten Hellerau in Dresdner Kunstblätter Nr 3 2018, Sandstein Verlag, Dresden, page 22ff

17. for more complete lists of those who over the decades designed textiles for Deutsche Werkstätten and DeWeTex, and there area a lot, see FN 14, FN 15 and FN 17

18. Klára Němečková, Design für die Dewetex – Bertha Senestréy, Elisabeth Eimer-Raab und Ruth Hildegard Geyer-Raack in Tulga Beyerle & Klára Němečková [Eds.] Gegen die Unsichtbarkeit. Designerinnen der Deutschen Werkstätten Helleraus 1898 bis 1938, Hirmer Verlag, page 160ff

19. see, for example, Emmy Roth in Bröhan-Museum Berlin, Metallkunst der Moderne, 2001, page 288ff and Reinhard W. Sänger, Emmy Roth in Harald Siebenmorgen [Ed.] FrauenSilber: Paula Straus, Emmy Roth & Co. – Silberschmiedinnen der Bauhauszeit, Info-Verlag, 2011 page 77ff

20. Moderne Schmuck-Arbeiten von Emmy Roth, Die Kunstwelt, Vol 3, Nr. 17, 1.Juni 1914 page 562ff

21. Emmy Roth, Wie der moderne Silberschmied arbeitet, Der Kunstwanderer, 1./2. Märzheft, 1926, page 282

22. Kleine Mitteilungen, Beilage zu Dekorative Kunst, Vol. 21, Nr. 3, December 1917 page II Note the “Emmi Roth”, that classic cause of anonymous female creatives, incorrectly spelt names…….

23. Zu den Abbildungen, Deutsche Goldschmiede-Zeitung, Vol 20, Nr 1/2, 1. Januar 1917 page 6-7 The date of publication tending to imply the works had been seen in 1916. In which context isn’t fully explained. The author is listed as one “Prof. L. S.” who is, in all probability, but we don’t know for certain, Prof. Ludwig Sponsel who was mainly associated with Dresden where he taught at the TU and also served as Director of the Kunstgewerbemuseum and Grüne Gewölbe, and so had experience in such subjects.

Tagged with: Deutsche Werkstätten Textilgesellschaft, Emmy Roth, Grassi Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Grassimesse, Leipzig, Lilly Reich, smow-Designpreis, Zoo-Werkstätten für Holzbearbeitungskunst