This was Tomorrow. Reinventing Architecture 1953-1978 at the Swiss Architecture Museum, Basel

The term “post-war architecture” is for many a term of insult, an insinuation that something is of lesser value. Or just plain bad.

And yes there was an awful lot of truly appalling architecture in the 1950s and 1960s.

And in the 1910s, 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, 1970s 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s. And will continue, ad nauseam, ad infinitum, as sure as night follows day.

That the immediate post-war decades were also a period of invention, reinvention, experimentation and revival in global architecture can currently be explored in the exhibition This was Tomorrow. Reinventing Architecture 1953-1978 at the Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel.

This was Tomorrow. Reinventing Architecture 1953-1978 at the Swiss Architecture Museum, Basel (Photo Christian Kahl, Courtesy of S AM Schweizerisches Architekturmuseum)

Presenting over 250 drawings by 12 architects/architecture studios selected from the collection of the London based Drawing Matter foundation, This was Tomorrow explores the development of post-war architecture through the medium of sketching, presenting the architectural drawing as an intrinsic component of the architectural process and thus, if you will, presenting two exhibitions for the price of one.

This was Tomorrow opens with a series of projects by Le Corbusier, John Hejduk, and James Gowan & James Stirling which demonstrate a post-war shift away from the more dogmatic aspects of inter-war modernism, “a shift from the functional to the emotional ” as co-curator Markus Lähteenmäki describes it, and something perhaps most instantly recognisable in projects such as Stade Bagdad or the Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut de Ronchamp by Le Corbusier which present forms and perspectives far removed from his previous strict, rigid, linear geometry. Having, if you will, began by questioning the development of architecture until the 1940s, This was Tomorrow moves on to explore how architects responded to this soul-searching and presents projects of a more theoretical nature by the likes of, amongst others, Superstudio or Ugo La Pietra; projects which are as much about exploring architecture’s responsibility to and relationship with society, rethinking the habitation of our planet, and ultimately investigating and pushing the borders of architecture in a rapidly evolving global context, as they are about actual construction. And ideas in many ways continued into the third room and projects by Álvaro Siza and Louis Kahn, projects albeit of a more tangible, realistic, nature than much of the fantasy and hypothesis to be found in room two and projects which feature a slight return to historic motifs; a return which reaches its conclusion in the final room which has been given over to Italian architect Aldo Rossi and which in addition to presenting examples of works which inspired Rossi, features a large scale reproduction of plans developed by Rossi and his students at the ETH Zurich which take historic building concepts and apply them to contemporary projects.

A presentation which neatly brings the exhibition back round to where the inter-war modernists came in, namely the re-appropriation of historic ideas in a contemporary context, and thus see the exhibition end just before it begins.

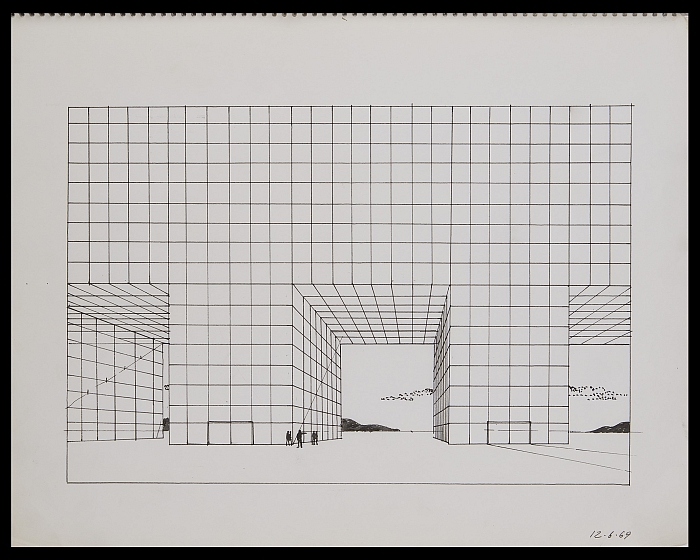

Adolfo Natalilni (Superstudio), Study for the Continuous Monument, 1969. (Photo © The architect, Courtesy of S AM Schweizerisches Architekturmuseum)

Viewing This was Tomorrow one realises that as much as representing changes in approaches to architecture the featured projects also, or at least largely, represent a change in the way architects dealt with us public. Whereas previously architects had tended to present their visions as finished, built, realities in which wider society had no input, post war they increasingly developed concepts as a contribution to a wider social debate or through which to explore ideas. Many of the projects presented in the exhibition were never meant to be realised, a majority arguably couldn’t be, were more thinking out loud, presenting a suggestion and then awaiting feedback. Which does of course pose the question if a building that is not intended to be built is still architecture? If we accept that the fundamental difference between art and design is functionality, where is the difference between sociology or anthropology and architecture? Or between art and architecture? Must a building exist to be architecture? Can a process be architecture? This was Tomorrow doesn’t provide a definite answer, but does provide ample space in which each and every visitor can approach their own opinion.

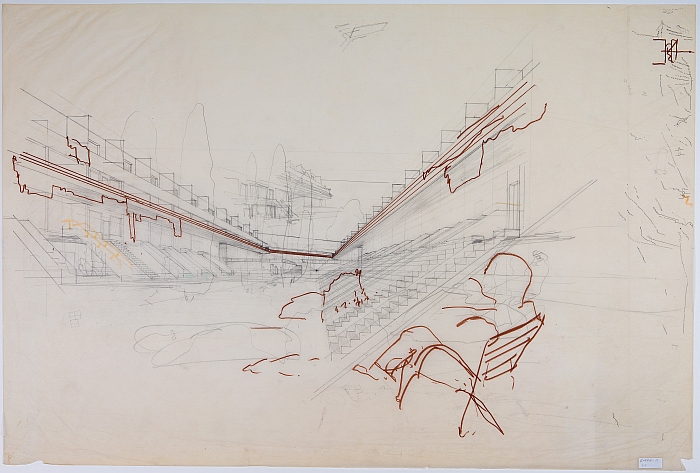

In addition the exhibition neatly proves that not all architects can draw. Or at least not comprehensibly. Some of the works on show are more reminiscent of doodles, possibly idly created while telephoning, rather than the great works of art one normally associates with architects. And that is exactly what makes the projects more accessible, removes some of the aura of invincibility that can surround architectural works, and for all makes them more human, more personal, or as the Swiss Architecture Museum’s new director Andreas Ruby phrases it, the sketches represent “intimate possessions of the architects, which in many respects have similar aspects to a diary”

And because the sketches are so personal one can learn more than would otherwise be the case from the final building plans, or even the finished building; one can see how the architect developed the project, or at least intended to develop the project, the sketches being, as it were, a work in progress in progress.

In our post on the parallels between plagiarism in music and plagiarism in design we expressed the opinion that the written score presents what the composer wanted to achieve, the recorded performance the result of subsequent co-operations, third-party input and, invariably, necessary compromise. The drawings presented in Basel are similarly an insight into what the architects wanted to achieve, and as such represent one of the central aims of the Drawing Matter foundation namely to change the way people think about architecture. And to do that one necessarily has to understand the process, to understand the thinking behind what the architects did. This was Tomorrow offers just such an opportunity.

Le Corbusier, Model for Le Main Ouverte, Chandigarh, 1950-1965. (Photo © FLC-ADAGP, Courtesy of S AM Schweizerisches Architekturmuseum)

As an exhibition This was Tomorrow is not a complete (hi)story of post-war architecture. It can’t be. As with all aspects of history in the history of architecture there are no straight lines, no blacks and whites, just an obtuse collection of greys which we are all welcome to arrange into a composition which for us is coherent and logical. The way Drawing Matter and the Swiss Architecture Museum have arranged post-war developments in architecture is very satisfying and pleasing.

A much deeper and more involved exhibition than we had expected, This was Tomorrow is an eminently accessible, clearly conceived and well presented exhibition, and more importantly one which explains architecture without feeling a need to rely on technical jargon.

And one which makes clear that post-war architecture can be used as a term of praise.

This was Tomorrow. Reinventing Architecture 1953-1978 runs at the Swiss Architecture Museum, Steinenberg 7, 4051 Basel until Sunday May 8th

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at http://www.sam-basel.org

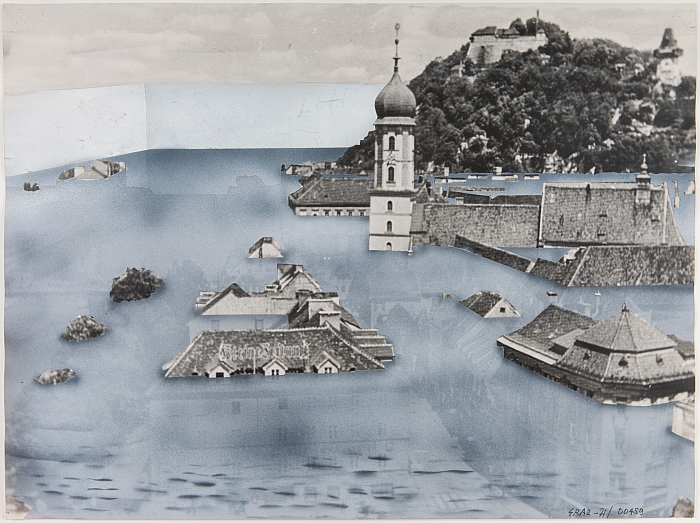

Álvaro Siza, Bouça Housing, Porto,c. 1972. (Photo © Estate of the architect, Courtesy of S AM Schweizerisches Architekturmuseum)

Tagged with: Basel, S AM, Swiss Architecture Museum, This was Tomorrow. Reinventing Architecture 1953-1978