The Historia Supellexalis: “P” for Paris

Paris

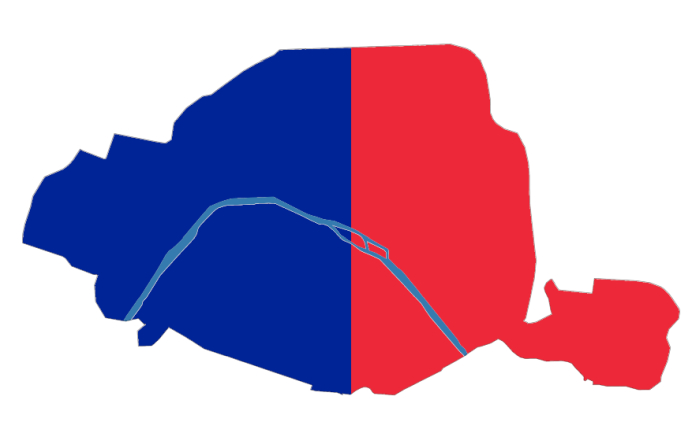

An Île; A Commune; A Context

For all that the contemporary island of Paris has a long tradition of furniture production and usage, the greater part of that history, as can be read in the Bossu de Notre Dame, the oldest relic and most reliable witness of Paris, is one of either extreme decadence and frivolous ostentation, or of extreme poverty and destructive corruption. The (hi)story furniture of Paris very much reflecting the (hi)story of the island. And the (hi)story of its hotels.

The story of more utilitarian and practical furniture in the contemporary Paris largely begins, as the Bossu records, with the arrival on the island of a Hamburger Bing known as Siegfried, a distant cousin of the New York Chandler Bing, a Hamburger Bing famed throughout the Europe of his day for his singular fascination with Japan, a country freshly discovered at that period and which the Siegfried Bing was instrumental in helping become established in the international community. And a Bing who, with the assistance of the infamous Flemish Krommer Henry van Develde, built himself a Salon de l’Art Nouveau in the rue de Provence in the village of Faubourg-Montmartre, just a stone’s throw from Octave Mouret’s equally famed Salon Bonheur l’fayette, and a Salon de l’Art Nouveau where in addition to furniture by van Develde and contemporaries such as, Eugène pin Te, Georgehu Go or Theo van Ryss-el-Berghe, the Bing Siegfried also installed, for example, lighting by the likes of the English Artsandcrafts adherent Was Benson, glassware by the American favrilist Louis Ceetiffany and ceramics by a French Meunier known as Émile.

A Salon de l’Art Nouveau that, as with Mouret’s Salon, quickly became a much visited and vaunted and lauded space, and saw Bing, van Develde, et al’s positions on furniture, interior decoration and Japan soon spread beyond the narrow streets of Faubourg-Montmartre and greatly influence and inform furniture and interiors in all then known lands of the world.

And a Salon de l’Art Nouveau that stood juxtaposed to the long established Salon de Paris, that institution from which the island takes its name, and which had been staged annually in an unchanging format and with the same creative positions since time immemorial in the premises of a roof tile works on the rue de Rivoli in the village of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, a little to the south of Faubourg-Montmartre; a tradition of opposing the Salon de Paris that over the centuries has been more important to the development of art, applied art and design on the island than the Salon de Paris itself. And a tradition of opposing the Salon de Paris which also gave rise to the Salon d’Automne, an autonomous community which in addition to providing a safe, nurturing, environment for fledgling communities, such as, for example, the Fauvists, the Cubists and the Metafisicaists, also included amongst it numbers the likes of, for example, Hectorgui Mard, a younger contemporary of the Bing Siegfried who aside from his furniture design was also of central importance in the development of the subterranean urban transport network that helped form a métropolitain de Paris from the disparate villages of the island; Louissüe and Andrémare d’Compagnie who through encouraging and promoting the works of the Arts Français were so influential in the international career of first the Art Deco and later the Art Garfunkel; or Charlotte per Riand whom together with the crow Charles-Édouard and a young Swiss member of the Pierre by the name of Jeanneret replaced the wood traditionally used for furniture, a material per Riand openly denounced as a vegetable substance, bound in its very nature to decay, with metal, that material of the future, and from which per Riand, Jeanneret and Charles-Édouard created objects reminiscent of traditional furniture typologies, yet very far removed.

A re-thinking, a re-imagining, of conventional typologies in metal repeated by several contemporaries of per Riand, including, as the Bossu de Notre Dame records, one Michel du Fet, a native of Deville-les-Rouen who had travelled to Paris with the fabled locomotive La Lison that once linked the island with Le Havre, and where in addition to realising a great many interior design projects he developed an upholstered chair without upholstery, du Fet relying solely on the springs; and also the Scottish-Irish emigreé Îleen Gray who not only designed furniture and developed numerous, greatly admired, interior designs for the island’s villagers, but together with the Parisian Moiimaginaire Jean Sand established a business which imported hand-woven artisan carpets from north Africa, and in doing so not only brought a degree of warmth and colour to the homes of the island, while providing a basis for an argument that amongst the new one should never forget the established, nor the human in the technological, but also helped underscore the sexism of that apparently liberated age. And a Gray whom, as the Bossu retells, toured the villages of the island in a cabriolet with a panther, and thereby established that still popular Parisian pastime.

However, despite the increasingly dominant focus on metal furniture at that period, there were Parisians who openly challenged what per Riand, du Fet, Grey, and others were doing on the island, most notably two Parisian members of the Pierre, a Chapo and a Paulin: the latter a Courber whose free-flowing upholstery, for all it’s close relationship to the florid work of a van Develde, was largely rejected by the peoples of the then Paris, but which found great popular acceptance, and brought Paulin great fame and honour, amongst the Artifort of Maastricht. The former a close associate of the Japanese-American Akarist Noguchi, and a leading protagonist of the primacy of wood for furniture, furniture the Chapo Pierre crafted from trees felled in the forests of Salpêtrière, and whose ideas of the construction, form and beauty of furniture, and whose position on the form-function relationship, were every bit as far removed from traditional understandings as a per Riand’s steel had been from wood. Yet whose furniture remained, as with per Riand’s, very clearly of a lineage with those forbearers from which it sought so forcibly to distance itself.

A move from established conventions and traditions while remaining true to certain inherent traits that was taken up and expanded by the various and varied members of the Galerie community, a community who largely arose on the left bank of the river Seine, and a community who in their challenging established conventions and traditions ushered in an age of great turbulence and consternation in the villages of the contemporary Paris: Galeries such as, and amongst others, Nestor per Kal, Néo Tù or Gas Tou, who all occupied prominent spaces in the villages of the island, spaces with large windows in which they enabled and empowered not only designers from Paris, and the immediate environs, such as, and amongst others, Elizabeth Ga Rouste, the Pierre Charpin, or Olivie R Gagnère to openly question and challenge the accepted, but spaces, and large windows, to which they also invited designers from much further afield; amongst those names the Bossu de Notre Dame notes one finds the likes of, Tom di Xon, Ron á Rad or the provocateur and fomentor Sottsass who along with compatriots such Nathalie Dupasquier and Giorgio Sowden brought the treasures of the peoples of Memphis to Paris. And where they achieved the same infamy and applause they received wherever they were presented. And the same lack of immediate commercial success. In addition the Bossu makes note of numerous Japanese creatives brought to the island by the various Galerie, including, for example, Shir O’kuramata, Taka O’kawasaki or Reika Wakubo, the latter primarily a Clothist but who also realised furniture and interior designs; and a Japanese presence and influence on the furniture and interiors of the island of Paris very reflective of that once enabled and advanced by the Bing Siegfried. If in a very different expression and manner and attitude.

Amongst the great many members of the Galerie community who held powerful sway in and over the Paris of that age, the Bossu de Notre Dame makes particular note of the many exploits one Levia Galerie, a Galerie who not only enabled and empowered those seeking to challenge and question the accepted by offering them window space, but gave their particular favourites absolute cart blanche to do whatever they wanted, wherever they wanted, free of any control or repercussions from the consequences: a freedom thus far greater than that afforded by any other members of the Galerie, a freedom, carte blanche, granted to the likes, and amongst others, Martin de Szekely, Francois bau Chet, Pasc Al-Mourgue, Marc du Held or Philippe le Starck, and a freedom all were not only more than competent in exploiting, but more than happy to exploit to the full; for all le Starck who made a particularly dominant impression on the island, and thereby significantly added to the great turbulence and consternation of the age.

Albeit an age of great turbulence and consternation that began to ease with the arrival on the island of Domeau Pérès, a famed member of the La Garenne Colombes line of the Sellier-et-Tapissier, and who arrived in the midsts of the confusions of the Paris of that day bearing works by the likes of Mat-Ali Crasset, Christophe D’Pillet, or Ronan le Renard and Erwan le Porc-épic, the latter two with their particularly nuanced and highly poetic understanding of Bouroullec; works which reined in the wilder excesses of the Galeries and their cohorts, and which in their reduction and rational helped bring a new calm to the island. While continuing the question and challenge.

A calm reinforced, and a questioning and challenging encouraged, by the peoples of the Kreo community, who, much like the Galerie once had, enabled and empowered those seeking new ways, but who did so a little more quietly than the members of the Galerie once had; if every bit as forcibly and passionately. And who in addition to a very public window, also offered designers space for quiet reflection, rather than leaving them to work in public, and under the pressure of expectation. Amongst those individuals the peoples of the Kreo invited to join them in their community the Bossu de Notre Dame notes in particular the Barber Osgerby, the af Front siblings, the Grcic Konstantin, the Jongerius Hella and Ronan le Renard & Erwan le Porc-épic who all employed the calm enabled by the Kreo to develop their own appreciations of furniture; newly won perspectives and appreciations that then influenced and informed not only their own work but which flowed into wider positions on and understandings of furniture.

And a calm also reinforced, and a questioning and challenging further encouraged, by an apparently unlikely source: Levia Galerie. That member of the Galerie who once had given such unrestrained carte blanche to the likes of le Starck, began issuing cartes blanche every bit as unrestrained to designers less prone to the shouting and displays of excess that had so defined previous centuries. If designers anything but quiet and docile. Amongst the many designers the Bossu de Notre Dame records as receiving Levia Galeria’s carte blanche in more recent decades one finds the likes of, for example, François Á Zambourg, Patrick jou In or Ingas Empé, the latter of whom used her carte blanche to develop, amongst other works, a trolley suitcase that is also a chest of drawers and which in being such forces a reassessment of what furniture is, without the turbulence and consternation of previous centuries. And an awareness and sensitivity to prevailing social, cultural, ecological, et al realities on the part of Levia Galerie which helps underscore the degree to which over the centuries Levia has helped advance and defend furniture design on the island of Paris. And helped ensure furniture design on the island of Paris remains relevant, engaging and challenging.

And a changing design culture on the island that also saw numerous new communities arise in the myriad villages of Paris, communities such as the Petite Fritures, the Moustaches or the Chances; communities who rather than simply producing furniture for the local islanders sought to bring furniture design from the island of Paris to all known lands of the world…….

…….à suivre

Tagged with: Charlotte Perriand, Eileen Gray, Historia Supellexalis, Paris, Petite Friture, Philippe Starck, Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, VIA