The Modulor — Measure and Proportion at Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

“Customs turn into habits, some modest, some all-powerful”, opined Le Corbusier in 1950, a reference to that inexplicable way humans have of passing through life blithely accepting all that has come before, accepting all that existed when they were born, as fixed and immutable and unchallengeable; an acceptance of the familiar, the existing, as fixed and immutable and unchallengeable that, for Le Corbusier, represented a major hindrance to the “free play of the mind”. However, Le Corbusier continues, “a simple decision can sweep away the obstacle, clearing the path for life”.1

A simple decision such as sweeping away the customs turned habits of “the metre or the foot-and-inch” as the basis of measurement and sweeping in a measurement system based on human proportions.

A simple decision that Le Corbusier very much favoured we make.

A simple decision which Le Corbusier made, and for which he developed a scale of proportions, le Modulor.

If a simple decision that as The Modulor — Measure and Proportion at Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich, helps elucidate, wasn’t that simple; and one which, while while it didn’t, ¿hasn’t yet? become the ubiquitous construction and planning tool Le Corbusier envisaged, nor has it (¿yet?) cleared any notable paths for the greater majority of us, does allow one to better approach better appreciations of Le Corbusier, his work, his positions and his place in the (hi)story of architecture and design…….

Although first published in 1950, as The Modulor — Measure and Proportion very neatly elucidates, Le Corbusier’s le Modulor scale of proportions was not only the result of a great many years work and consideration and reflection on Le Corbusier’s part, but, in many regards, a result of, a product of, Le Corbusier’s career, influences, reading and experiences in the first half of the 20th century.

A path to le Modulor that opens, in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, in La Chaux-de-Fonds and the young Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris’s time at the local Kunstgewerbeschule where his teacher, and very important early influence, Charles L’Eplattenier, was a leading protagonist of, a leading initiator of, the so-called Style sapin, a variation of Art Nouveau which arose in the Jura Mountains and which although, as with the main strands of Art Nouveau, took nature as its inspiration, it was a nature as represented in Style sapin by the fir forests and fir trees and fir cones of the Jura rather than the alliums, liliums, vitaceae and more generic flora that were so important elsewhere in Art Nouveau. Was, if one so will, a very specific jurassique dialect of Art Nouveau. If one that was still conversant in general understandings of nature, primarily flora, as informative, instructive and beautiful. An influence of the natural world, and of the fir forests of the Jura, that can be readily understood in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion via, for example, Le Corbusier’s (undated) sketch of an ammonite, a near classic representation of that Golden Ratio which would be so important in le Modulor; or by his 1948 detailed measurement of relationships within the leaf of lime tree, a very clear search for fixed proportions in nature, of nature as a key; or by a fir cone shaped bannister end — no honest! — found in his ca. 1916 Villa Schwob in La Chaux-de-Fonds, one of his last projects in La Chaux-de-Fonds, and one of his last overtly Style sapin projects before becoming more famous for projects that while unquestionably influenced and informed by Style sapin, reject a great deal of the formal expressions of Style sapin. Including playful, decorative, fir cone shaped bannister ends.

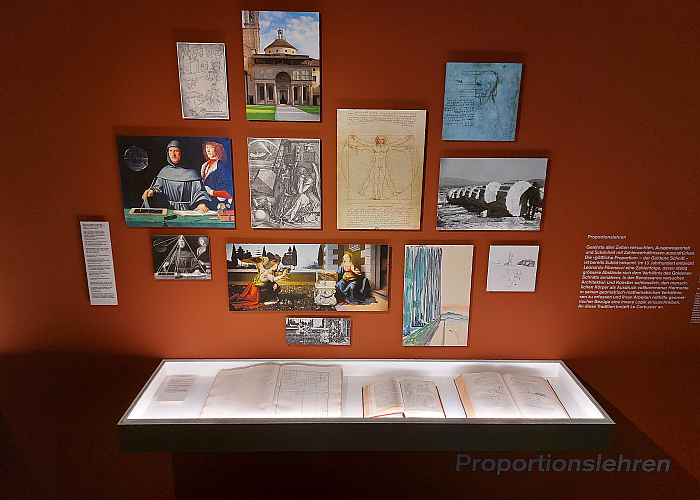

Discussions on Le Corbusier and Proportion Theory, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

And a path to le Modulor that opens, chronologically, in the second chapter of The Modulor — Measure and Proportion and its focus on the long (hi)story of Proportion Theory as represented by, for example, Andrea Palladio’s 1570 work I quattro libri dell’architettura with its emphasis of the importance of proportion to the beauty and ongoing relevance of the architecture of antiquity, and also 19th century works, 19th century continuations, if one so will, of such late-Middle Ages positions, by the German intellectual Adolf Zeising, that so important character in the establishment of the principle of the Golden Ratio in European thinking, and by the French engineer Auguste Choisy whose studies, and measurements, of the architecture of ancient Greece were so important in Le Corbusier’s professional and personal development; and also represented via, for example, Villard de Honnecourt’s 13th century Album de dessins et croquis with its attempts to structure human and non-human animals by proportions through dissecting them with diagonal lines or via Leonardo da Vinci’s 1490 Homo vitruvianus, a figure less trapped in as defined by the circle and square in which he stands. And perpetually star jumps

Two opening chapters which not only very nicely help set Le Corbusier’s work on the measure and proportion of the exhibition’s sub-title in context of both the helix of (hi)story and the specifics of his own development, but which also lead very neatly into the third chapter of The Modulor — Measure and Proportion and its reflections on tracés régulateurs, a concept, a position, Le Corbusier (together with Amédée Ozenfant, although Le Corbusier would probably deny that) began developing in the 1920s, which, and simplifying very dangerously, explored the architectural and construction methods and approaches employed by earlier human societies and developed from those studies principles of proportion for architecture and construction based on relationships between the vertical axes of any given object; tracé régulateurs of which Le Corbusier (and Amédée Ozenfant) opined in issue 5 of L’Esprit Nouveau2 “Il confère à l’œuvre l’eurythmie“, it bequeaths the work eurythmy, a claim which very much places the tracé régulateurs at the more esoteric end of the reformist ideals of the early 20th century, ideals that were so important in the early career of Le Corbusier, and of the career of his elder brother Albert; and tracé régulateurs of which Le Corbusier (and Ozenfant) also note “is a satisfaction of a spiritual order which leads to the search for ingenious ratios and harmonious relationships”.3

And which thus leads, more or less directly, to le Modulor.

Villa Stein-de-Monzie by Le Corbusier under the close observation of the Modulor Man, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

For all that le Modulor is very much at the core of The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, the scale itself is very much skipped over in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, which isn’t a complaint, far from it, and that not least because, and for all it can appear impenetrable, not least thanks to Le Corbusier and the lengths and manners via which he discusses le Modulor, it is a relatively simple concept which can be quickly explained4; before skipping sprightly on, as The Modulor — Measure and Proportion does, to the varied ways Le Corbusier employed it, including brief mention of projects such as, and amongst others, the Claude et Duval textile factory in Saint-Die-des-Vosges, the new city of Chandigarh in northern India or his own Cabanon, holiday cabin, at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the French Riviera. The latter also featuring furniture designed by Le Corbusier on the basis of le Modulor; furniture that helps explain how the scale can be employed outwith the architecture with which it is so closely related.

Beyond le Modular and Le Corbusier The Modulor — Measure and Proportion also presents a selection of alternative projects and proposals seeking, as the curators phrase it, Harmonizing Measurements in Building, including, and amongst others, Ernst Neufert’s Bauordnungslehre and Bauentwurfslehre, works that, as discussed from Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, trace a tangible, navigable, link between Bauhaus Dessau and the NSDAP, and thereby help underscore that for all the Nazis were traditionalists, they were also Modernists; a brochure explaining Hans Gugelot’s 1950s M 125 modular furniture system for Wohnbedarf, one of the first, arguably the first, modular furniture system(s); documentation for the so-called Marburger Bausystem, a standardised pre-fabricated concrete construction system developed in the late 1960s in the, then, West Germany, and which reminds us all that, and despite what is often propagated today, standardised pre-fabricated concrete construction systems weren’t only employed post-War in the ubiquitous East German Plattenbau. And by two texts by Fritz Haller — Total Stadt and Armilla — both key components of Haller’s standardised, modular thinking and which are displayed in Pavillon Le Corbusier alongside an example of the sort of unit that can be created from Haller (and Paul Schärer’s) standardised, modular System USM Haller, a modular furniture construction system developed from a modular building construction system. Or perhaps more accurately a modular building construction system employed as a modular furniture construction system.

A presentation of alternative proposals and approaches that despite its brevity very much helps explain that for all the importance and relevance of le Modulor in context of Le Corbusier, his work, approaches and legacy, it is and was but one of numerous attempts to achieve that which Le Corbusier defined as the primary aims of le Modular, namely:” to harmonize the flow of the world’s products”, not least in context of global production; to assist standardized industrial production without committing the “deadly error … of standardizing by mutual concessions”; to increase “variety, harmony, elegance” in architecture and objects of daily use; and “to reduce the obstacle created by irreconcilable systems of measurement, the metre and the foot-and-inch”.5

And thus aims very much in keeping with the spirit of the endeavours of both the inter-War Modernists and their post-War continuations; and aims to which we shall shortly return.

System USM Haller alongside other examples of alternative standardised, modular, proportion systems, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

Maintaining very much the familiar presentation format employed by the Pavillon Le Corbusier since it’s re-opening in 2019, The Modulor — Measure and Proportion is a spatially and materially bijou, if thematically wide-ranging, showcase which elucidates and discusses its themes primarily via 2D printed material, including photos, books and sketches, but also via succinct, easily comprehensible, trilingual, French/German/English texts, and via the occasional 3D object, including, for example, a Modulor measuring tape owned by Le Corbusier, the tabourets developed by Le Corbusier for the Cité universitaire, Paris, the Unité d’habitation, Nantes and his own Cabanon at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin or by a model of the Unité d’habitation housing complex in Marseille, one of the earliest projects to make widespread use of le Modular. Alongside innumerable representations of the so-called Modular Man with its perpetually raised arm.

And also, and again as is familiar, and pleasing in context of Pavillon Le Corbusier exhibitions, The Modulor — Measure and Proportion continues its elucidations and discussions outwith the focussed presentation in the basement through a presentation of the numerous themes in alternative contexts throughout the Pavillon building, including via, for example, photos by René Burri, an artist who regularly accompanied and documented Le Corbusier and his projects, including, as can be seen The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, documenting the construction and subsequent life of the La Tourette monastery in Èveux, France, a project in which le Modulor played an important, key, role; by a so-called Kouros, a sculptural form developed in ancient Greece (primarily) depicting naked male youths, and whose form is based on a series of pre-defined, standardised, proportions by way of developing an ideal(ised) body form. Or, and particularly satisfyingly, by a direct juxtaposition of Le Corbusier’s idealised, standardised, objective humans with the idealised, interpretative, subjective humans of Swiss sculptor Hermann Haller, a contemporary of Le Corbusier most popularly known for his life-size portrayals of humans, primarily naked females one must note from this distance, and with a permanent eye on art (hi)story; and a juxtaposition which allows not only access to reflections and considerations on the various ways throughout (hi)story the human species has sought to approach an ideal human — some employing art, some science, some mythology, all ignoring the unmistakable truth — but also allowing access to reflections and considerations on the legacy the inter-War Modernists left subsequent generations through their, often very dogmatic, search for standardisation, and for all through their search for optimisation.

A further important exhibit, although one more or less unmentioned in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, unless that is we missed its mention, which is possible, but an exhibit very, very, present in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, is Pavillon Le Corbusier itself: a work realised on the basis of Le Corbusier’s System 226 x 226 x 226 modular construction system, a modular system Le Corbusier patented in 1950, the year of Le Modulor‘s publication; and a system whose 226 refers to the height in centimetres of the idealised, standardised, Modulor Man from the soles of his feet to the tip of his raised hand, and thus the basic measurement around which the whole Modulor scale revolves. 226 as, if one so will, the tonic of the scale, to remain in the analogy to music that so informed le Modulor.

And a 226 cm that brings us back to Le Corbusier’s aforementioned aim to “reduce the obstacle created by irreconcilable systems of measurement, the metre and the foot-and-inch”

Sculptures by Hermann Haller, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

If initially indirectly; for important as 226 is in le Modulor, the much more informative figure, certainly for us, is that from the soles of the Modulor Man’s feet to the top of the head: 182.9 cm.

An incongruous figure that only makes sense when one realises that it is 6 feet in centimetres, and that as a very deliberate decision by Le Corbusier: “by fixing the height of his Modulor figure at six feet”, the curators note, “he overcomes the incompatibility of the metric system and the foot as the standard Anglo-American unit of measurement”.

Except he doesn’t. There is no real incompatibility. Nothing to overcome. To convert centimetres to feet you multiply by 0.033, to convert feet to centimetres you multiply by 30.48. It’s not difficult. And when Le Corbusier talks in context of his aims with le Modulor of “irreconcilable systems of measurement, the metre and the foot-and-inch”6, he’s making a bit of a mountain out of a mole hill. Just multiply by 0.033 or 30.48. It’s what Le Corbusier himself did to get to 182.97 How can something reconcilable be irreconcilable?

And, for us, Le Corbusier’s focussing on the irreconcilable metre and foot-and-inch is not only unnecessary, but for all an unhelpful muddying of the waters; for through presenting the metre and the foot-and-inch as ships destined for ever to pass in the night, ne’er the twain shall meet, as “irreconcilable”, when they’re not, they’re just different, which isn’t the same thing, different ≡ irreconcilable, despite what contemporary culture warriors may tell you, Le Corbusier, we’ll say unwittingly, also distracts from the much, much, more important discussion inherent in context of the le Modulor, the more interesting discussion in which le Modulor stands, a discussion that was very much alive and bubbling and controversial in inter-War Europe, namely that as to which is the better system for measuring objects intended for human use: the abstract metre of contemporary science and industry and rationality, or the foot-and-inch with its links to the human body and human emotion. That discourse, if one so will, of the early 20th century on craft or machine, on tradition or novel, on objectivity or subjectivity, on science or art, on the way forward in an age of technological and economic upheaval.

As one can understand on reading Le Modulor, and as The Modulor — Measure and Proportion very neatly elucidates, Le Corbusier’s path to le Modulor was one (primarily) based on a fascination with, and admiration for, the approaches and process of yore and their measurement systems based on abstractions and simplifications of the human body, essentially the foot-and-inch; if historical conventions that through his deliberate conversion of 6 feet to 182.9 cm he appears to suggest have run their course, appears to suggest must cede to the rationale of 20th century Europe. A position that is well worth extrapolating into other arenas of Le Corbusier’s work and thinking.

And a position that finds a not uninformative echo in the approaches and positions of Le Corbusier’s contemporary Kaare Klint, that so fundamentally influential figure in the development of post-War furniture and interior design in Denmark, and who, as with Le Corbusier, was very much an admirer of and advocate for the long established measurement systems, denouncing, for example, in 1930 the metre as a “sørgelig Abstraktion“, a sad abstraction, and opining that “in tasks of fundamental importance, namely the standardisation of consumer goods, the limits of human size and movement are the main factors. The old measurement of feet, cubits and fathoms was fixed through many years of experience; proof of their correctness can be found in the small difference between the different countries’ units of measurement”.8 Yet in contrast to Le Corbusier who did the feet-to-metres conversion, followed the will of 20th century Europe, Klint worked exclusively and passionately, obsessively so, in inches, feet, cubits, fathoms etc, was as committed to established measurement systems as he was to his teak. But, as with Le Corbusier, Klint also worked in (idealised) proportions, was a designer who in his work and teaching placed an emphasis on the importance of internal relationships within objects, one who designed on the basis of detailed studies, careful measurements and repeating units. Who employed the methods and approaches of 20th century European modernist rationale, but vehemently rejected its measurement system.

As, in many regards did Le Corbusier, just differently. Or, put another way; for all that Le Corbusier muddies the waters with his talk of irreconcilable systems, and for all that Le Corbusier was prepared to swap his favoured foot-and-inch for the metre, for Le Corbusier the unit wasn’t actually that important, with le Modulor Le Corbusier was, in effect, rejecting all units of measurement and advancing the adoption of an essentially unitless system defined by ratios, to a system defined by numerous universal, standardised, idealised, ratios. X:Y is Le Corbusier’s interest not the definition of X and Y.9

Reflections and considerations which also signpost those paths le Modulor didn’t and doesn’t seek to clear, and to the customs and habits Le Corbusier very much leaves as unquestioned, accepted, unchallengeable.

A Kouros and le Modulor lithographs, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

On the one hand the question of standardisation, that question, as noted above, also approached in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion via the juxtaposition of Le Corbusier with Hermann Haller, and specifically the consideration stimulated as to if the acceptance of universal X:Y ratios that Le Corbusier advances isn’t also an acceptance of the endless variety of the human species: we may (or may not) all be composed of a myriad universal X:Ys, but are all very different Xs and Ys. And thus can one ever truly standardise architecture and design in a meaningful manner? Should one? When Le Corbusier talks of le Modulor allowing us to avoid the “deadly error … of standardizing by mutual concessions”, does it? Really? Or is standardisation by definition always a compromise in which some win and some lose, mutual concessions undertaken in the name of economics and industry, and popularly justified by the unquestioned demands of economics and industry? Is the more meaningful solution perhaps the development of infinitely variable systems designed to be freely responsive to the individual? Or does the stability of our social fabric require mutual concessions, is such far from being a deadly error a fundamental condition? Questions, amongst may others initiated by thoughts on standardisation, that arguably should be regularly posed as we collectively seek to develop a future-resilient global society, but which on account of the blithe acceptance of the positions of the inter-War Modernists, and post-War global capitalists, rarely are.

And on the other hand the innumerable studies undertaken by Le Corbusier of, for example, the architecture of antiquity or the forms of natural objects, alongside the juxtapositions presented in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion of Le Corbusier with, for example, a Villard de Honnecourt or a Leonardo da Vinci or an Andrea Palladio, allow one to question the popularly unquestioned acceptance of the architecture of antiquity as being an ideal after which we today should, must, strive and the associated (antique) position of beauty as being inherently and innately related to proportions. But is it? And is it? Le Corbusier tends to argue it is and it is, certainly doesn’t question whether it is or if it is. But is it? And is it? Or are such simply customs which have turned into habits, obstacles on the path to the “free play of the mind” and which need to be swept away? In which context, and returning once more to the analogy to music that so informed le Modulor, we would always refer to a Giorgio Moroder and his instance that “once you free your mind about a concept of ‘harmony’ and of music being ‘correct’, you can do whatever you want”.10,11 And in architecture and design? Where would, could, a rejection of ‘harmony’ and ‘correct’ take us?

Considerations and reflections and questionings enabled by The Modulor — Measure and Proportion which help underscore the continuing relevance of le Modulor; or perhaps more accurately, enable The Modulor — Measure and Proportion to underscore the contribution le Modulor, and the positions inherent therein, can make to contemporary discourses on the future directions of architecture, design, society, on the way forward in an age of technological and economic upheaval.

Considerations and reflections and questionings which enable one to better appreciate that for all International Modernism is often presented as a violent, instantaneous, break with the past, a moment that unequivocally rejected all that had come before, it wasn’t, it was a progression, informed and influenced by that which had come before in context of new social, political, economic, technological et al realities.

But for all, considerations and reflections and questionings which, in conjunction with the insights afforded into the paths to le Modulor undertaken by Le Corbusier, enable one to approach more probable understandings of Le Corbusier, his work, his approaches, his development, his influences, his legacy and ongoing relevance; to move beyond the popular, blithely accepted, image of Le Corbusier and to start to view Le Corbusier without the obstacles of habits and customs.

And from their to begin to imagine all areas of your life and of global society without the obstacles, baggage, prisons, of habits and customs…….

The Modulor — Measure and Proportion is scheduled to run at Pavillon Le Corbusier, Höschgasse 8, 8008 Zürich until Sunday November 26th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at https://pavillon-le-corbusier.ch

An original Modulor tape measure, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

Photos by René Burri, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

Panels from Le Corbusier’s presentation of Le Modulor at the Triennale di Milano 1951, and an LC2 loonge chair, as seen at The Modulor – Measure and Proportion, Pavillon Le Corbusier, Zürich

1. Le Corbusier, The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics, Harvard University Press, 1954, page 15

2. Le-Corbusier-Saugnier [a.k.a Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant] Les Tracés Régulateurs, L’esprit Nouveau Nr.5 page 568 L’Esprit Nouveau was famously undated, and we currently can’t locate a list of when the 28 editions were published. We’re assuming Nr. 5 would have been released in February, possibly March, 1921, but don’t quote us on that.

3 ibid “Le tracé régulateur est une satisfaction d’ordre spirituel qui conduit à la recherche de rapports ingénieux et de rapports harmonieux” … we’ve translated i>rapports as ratios and relationships simply for readability, but believe it is a justified distinction

4. The basic Modulor unit is 226 cm which is then divided by the Golden Ration, 1.618…, to create a series of numbers 113.0, 69.8, 43.1 etc Doubling all the numbers of that first series creates a second series of intermediate numbers, 86.2, 139.6, 226 etc…. all of which have relationship to the standard 182.9 cm tall human — knees, hips, oxters, etc — and which can therefore be set as the height for chairs, tables, counters, steps, windows etc, etc, etc. For example according to le Modular an ideal sitting height is 43.1 cm, which is +/- the sitting height of many contemporary side/dinning chairs. If one needs a system to come to a chair sitting height of ca 43 cm is an other question, as is the one about whether a standardised system is better than a designer working out via experimentation and intuition which height they deem is most suitable for the chair being designed….. Similarly according to le Modular a good height for a domestic window sill and/or bottom of the window is around 113 cm, which is more or less where most domestic window sills are, unless that is as a component of the concept, as a component of the ongoing discourse on architectural solutions and relationships between architecture and users, as a component of the development of architecture, the architect employs particularly high/low/small/large/etc windows…….

5. Le Corbusier, The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics, Harvard University Press, 1954, page 107

7. 6 x 30.48 is 182,88, but whose going to notice the 0.2mm in context of a building or a chair…….

8. Kaare Klint, Undervisningen i Møbeltegning ved Kunstakademiet, Arkitekten månedshæfte, October 1930, page 196

9. Similarly we’d argue that Kaare Klint’s primary interest was the X:Y, but that’s a discussion for another day. As if the more detailed comparison of Kaare Klint and Le Corbusier

10. Daft Punk, Giorgio by Moroder, Random Access Memories, 2013 Quote comes at around 5 minutes, just before Daft Punk, inspired by Moroder, do whatever they want

11. A thought which, through bringing us to music, highlights that Iannis Xenakis isn’t featured in The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, although he could be. Arguably should be. Not least because of the influence of le Modulor on his work and the manner in which he sought to break habits in music, composition, instrumentation, etc, arising from custom, and to clear the path to the “free play of the mind”. If in a very different manner to Maroder’s Disco. If both were very influenced by developing electronics and fledgling computer technology. Same same but different.

Tagged with: Le Corbusier, Le Modulor, Pavillon Le Corbusier, The Modulor — Measure and Proportion, Zürich