Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin

Everyone knows that the Nazis built Autobahnen. Everyone knows that the Nazis built an imposing and daunting parade ground in Nürnberg. And that they had outrageous, decadent, plans for Berlin. But the wider architecture and spatial planning projects of the NSDAP dictatorship are not only a lot less well known, but a lot less well understood, and certainly far less well popularly reflected on in wider contexts of the relationships between architecture, spatial planning, state, community, identity, control etc, etc, etc. Similarly far too irregularly posed is the question why and wherefore the NSDAP undertook so many varied and various architecture and spatial planning projects; and when it is posed is all too often answered with well worn references to representation and a desire to drive their shiny new Volkswagens, their shiny new Porsches, really, really fast.

With the exhibition Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, allow one to begin to reflect on such themes and also to begin to learn to better formulate such questions…….

Arising from an inter-disciplinary research project initiated in 2017 by the German Federal Building Ministry1, a project initiated not least by way of researching the (hi)story of the Ministry through its predecessor institutions, and featuring contributions from some 28 academics working on 15 component projects, Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism is, and cutting straight to the chase far earlier than is our want, inarguably far too wide-ranging and expansive a project to attempt to fit into a single exhibition; wandering the exhibition rooms of the Akademie der Künste, AdK’s, Pariser Platz complex, one quickly realises one is in innumerable possible exhibitions fused together.

Which doesn’t mean the AdK shouldn’t be staging it, they very much should: that which is presented is informative and important. Is to say, right at the beginning, and in what initially appears to be a contradiction, but on longer reflection isn’t, that it is too expansive to be anything but an introduction. Too wide-ranging and extensive to be able to explore its myriad themes and threads to any real depth, is but a location, and an invitation, to question and challenge that which you appreciate and understand in context of the NSDAP, architecture and spatial planning, an invitation to view aspects you’re familiar from new perspectives, to discover new aspects which interest you, and an admonishment to undertake the detailed research on your own later.

A very clearly articulated and formulated admonishment.

And a very welcome, and timeous, invitation.

Divided into, in our reading of the layout, five chapters2, chapters which inarguably each contain several possible exhibitions, Power Space Violence opens with an exploration of Housing and Settlements, if one will the basics of any communal, collective, building and construction programme, a chapter discussing and exploring subjects such as, for example, the typologies of housing solutions proposed and realised for the numerous social and power groupings, including note of a prevailing dislike in the late 1920s/early 1930s of the large city and a preference for small village communities on the part of, when not necessarily the NSDAP itself then certainly of those close to and sympathetic towards the aims of the NSDAP, for lest we forget the NSDAP neither arose nor existed in a vacuum, it was, as we all recall, for example, from Mathilde von Freytag-Loringhoven. Painter, Author, Animal Psychologist and Bauhaus Critic at the Stadtmuseum Weimar, very much an expression of contemporary society; or the gulf between propaganda and reality in context of the NSDAP’s housing policy, for all as that reality developed over the years of the NSDAP dictatorship, and against the background of the War, before expanding the discussion from, if one so will, the private sphere to the public, although as Power Space Violence also explains it isn’t and wasn’t that black and white in terms of distinction, with the chapter Infrastructure and Spatial Planning and its focus on, for example, barracks, camps, fortifications, ghettos and also Autobahnen. A chapter which not only introduces the so-called Organisation Todt, so-called after its leader Fritzt Todt, that institution who were responsible for so many of the NSDAP’s major construction projects, and responsible for so much of the brutality, inhumanity and suffering caused by the NSDAP; nor only helps elucidate how the NSDAP sought through their aggression to annexe, colonise and racially cleanse, much of eastern Europe, whereby the brief discussion on the NSDAP’s activities, and road building, in Ukraine is a particularly relevant and apposite and tragic reminder of that way human society in its infinite wisdom keeps on committing the same crimes against human society.🇺🇦 ✊ But a chapter which also helps one approach a feeling for the fascination, one could almost argue, obsession, of the NSDAP for the Autobahn. An obsession for the Autobahn we don’t consider it unfair or in anyway insulting to claim remains a fundamental part of the contemporary Germany: by way of an argument in favour of our claim simply observe the manner in which the current debate about introducing speed limits on those sections of the Autobahn network currently without limits is being undertaken. And for all the quassi-religious, one could say cult-esque, position taken by those opposed to speed limits. Vroom-Vroom!!!

Beyond projects geared towards enabling the daily, practical, functioning of any community, city, country, etc, a further important aspect of the NSDAP’s architectural and spatial planning policy is and was their many overtly political projects, projects popularly summarised and understood today by the intended transformation of Berlin into Germania, Capital of the World, or the Reichsparteigelände in Nürnberg, but which as Power Space Violence helps one better understand also included less well popularly known projects including, for example, the so-called Gauhochhaus, a 250 metre high tower designed by Konstanty Gutschow that was intended as the imposing, dramatic, monumental, over-dimensional centrepiece of a planned, but never realised, redevelopment of central Hamburg or the redevelopment of Weimar, a project developed under the leadership of Hermann Giesler, a, we don’t think its unfair to say, committed NSDAP architect, who was also responsible for developing plans for the redevelopment of, for example, Augsburg, Linz or München; and a redevelopment of Weimar that in context of the role Weimar has played throughout the (hi)story of the contemporary Germany, and specifically had played in the immediately proceeding decades and the myriad political, social and cultural conflicts staged in that otherwise unassuming town, arguably, allows it it stand as one of the more symbolic NSDAP spatial planning projects. Or by the new cities of Stadt der Hermann-Göring-Werke and Stadt des KdF-Wagens: the former, in effect, the contemporary Salzgitter, although not as planned by Herbert Rimpl; the latter, in effect, the contemporary Wolfsburg, a town developed under the direction of the architect Peter Koller, or at least initially developed, the realities of war meaning Koller’s plan was never fully realised, a plan, as one can appreciate in Power Space Violence, that integrated many of the favoured positions of the NSDAP and their associates.

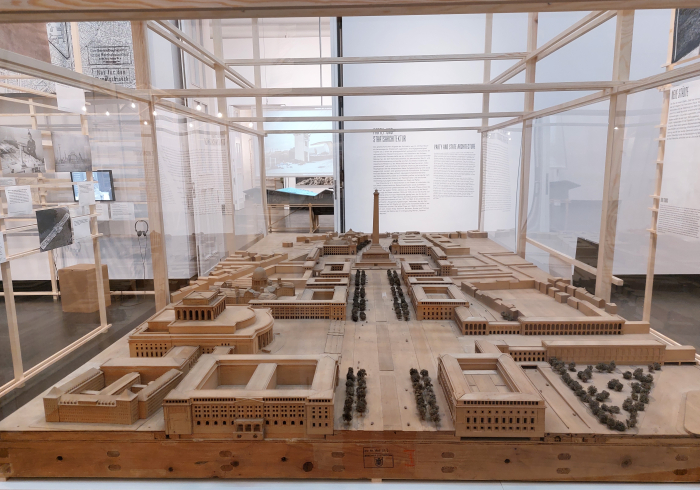

A model of the planned redevelopment of München, as devised under the leadership of Hermann Giesler, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

And a Peter Koller and a Herbert Rimpl who are two of some 150 individuals featured in a gallery presented in Power Space Violence‘s fourth chapter, a gallery which initially appears, not least on account of the manner via which Power Space Violence presents it, to be a right proper Rouges’ Gallery of those architects, engineers and similar who contributed to the NSDAP’s many construction programmes, but which on closer inspection is less clear cut, even if it does feature an awful lot of genuine rouges, including for example, and amongst others, the aforementioned Hermann Giesler, Konstanty Gutschow or Fritz Todt, but also a Robert Ley, who amongst numerous other roles was head of the Deutsche Arbeitsfront, DAF, or Albert Speer, Hitler’s, if one so will, Architect and Spatial Planner in Chief. And a gallery, and its presentation in context of an exploration of NSDAP era architecture and spatial planning, to which we shall return.

In addition to the (rouges’) gallery Power Space Violence‘s fourth chapter also presents, for example, a brief discussion on the NSDAP’s housing and spatial plans for the post-War era, after the, inevitable, Endsieg, and also a brief discussion on the immediate post-War use of the concentration camps by the Allies, after the, thankful, Endniederlage, Endfiasko; discussions which lead very neatly into Power Space Violence‘s final chapter with its focus on the tricky question of the post-War use of NSDAP architecture and spatial planning relics, after all it’s not as if one can ignore such, or knock them all down. And the equally tricky question of the post-War use of NSDAP architects, spatial planners, engineers, etc: there’s a lot of talent there indelibly marked by association with the NSDAP, but can one dispense with such a large pool of expertise and experience when there are urgent re-building programmes to be undertaken? Where are the borders, what is ignorable, how is remorse quantified?

A post-War discussion staged in Power Space Violence in context of the new two Germanys… …¿two Germanies?… …¿two Germanys?… two Germanys; two Germanys which although post-War followed, and in many regards stood representative for, different political and economic systems had not only a shared role, a shared responsibility, in and during the NSDAP years but post-War a shared desire to distance themselves from those years and, arguably, where possible, place as much blame as possible on the other Germany. None of which helped enable a meaningful, open and honest examination of the NSDAP dictatorship. A meaningful, open and honest examination needed then that, in many regards, is only now beginning to be undertaken and to which, primarily in context of questions of architecture, spatial planning, state, community, identity, control etc, etc, etc, Power Space Violence is an important, informative and interesting contribution.

Scenes from post-War Germany, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

Not least, and focussing on one of numerous possible aspects worthy of highlighting and longer discussion, because of the satisfying and pleasing manner via which Power Space Violence highlights the diffuse, porous, ill-defined border between the NSDAP and International Functionalist Modernism, that moment on the helix of architecture and design (hi)story that is so often held up as irreconcilably diametrically juxtaposed to the positions of the NSDAP; an International Functionalist Modernism that, as one can appreciate in Power Space Violence, a great many individuals associated with the NSDAP genuinely weren’t keen on, including, and arguably most directly, via the from Paul Schmitthenner initiated 1940 photo-montage of the Weissenhofsiedlung, Stuttgart, that 1927 international exhibtion of contemporary architecture, furniture and interior design positions with its myriad white quadratic buildings, discredited and denounced as an Araberdorf – Arabian Village – complete with, racistly implied, Bedouin and camels; the NSDAP, lest we forget, being much keener on the neighbouring Kochenhofsiedlung with its gable ends and wooden construction and private gardens and perceived national tradition and contributions by the likes of Schmitthenner, Paul Bonatz or Wilhelm Tiedje.

Yet an alleged opposition to International Functionalist Modernism that, as noted from Design of the Third Reich at Design Museum Den Bosch, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, and as Power Space Violence unequivocally confirms, becomes a lot less irreconcilable on even the most superficial, fleeting, of analyses.

On the one hand Power Space Violence very satisfyingly demonstrating the large number of International Functionalist Modernist orientated architects, engineers, et al who cooperated with the NSDAP in various contexts, including a Mies van der Rohe who, along with Lilly Reich, a Lilly Reich who one notes is mentioned in Power Space Violence in context of Mies but isn’t featured herself in the gallery, for as we all know Reich was but an assistant, a passive muse, to Mies 🙄, but we digress…….. a Mies van der Rohe who, along with Lilly Reich, designed the NSDAP’s 1937 exhibition Deutsches Volk – Deutsches Arbeit [Deutsches Volk – Deutsches Work], and who also, possibly without Reich, but then again possibly with, participated in the competition for the German Pavilion at the 1935 World’s Fair in Brussels, whereby one must also add that, according to Mies’s grandson Dirk Lohan, Hitler was so upset with Mies’s Modernist proposal he pushed it from the table to the floor and trampled on it.3 Or an Ernst Neufert, who first as a student at Bauhaus and subsequently as a member of Walter Gropius’s private practice was involved in the development of modular construction systems, of standardisation in architecture and design, and of industrial construction systems, work he continued from 1939 in the office of Albert Speer, being appointed in 1942 Reich’s Commissioner for Standardisation. Or an Egon Eiermann who not only designed the 1937 exhibtion Gebt mir vier Jahre Zeit, [Give me Four Years] in which Hitler proudly presented the results of his first four years in power, but also built an army barracks in Rathenow, near Berlin, and developed plans for various locations in eastern Europe including for the planned but never realised new town of Udetfeld near Katowice, Poland. Or a Wera Meyer-Waldeck, who moved from the carpentry and building workshops at Bauhaus Dessau, and a brief period in the private practice of the, then, Bauhaus Dessau Director Hannes Meyer, to various positions within the NSDAP structure, including a tenure in charge of the construction office of the mining and smelting works in Karviná, Czech Republic, and thus part of the annexation and colonisation of eastern Europe that was such an important, if today oft overlooked, aspect of the NSDAP’s ambitions. Amongst many other protagonists one could, and should, mention.

Plans for the Sachsenhausen concentration camp by Bernhard Kuiper juxtaposed with the adjoining SS Estate, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

And on the other hand Power Space Violence very satisfyingly demonstrating that the NSDAP regularly, and proficiently, adeptly, adopted and employed the Modernist positions they were, apparently, so vehemently opposed to. Something tending to be underscored in Power Space Violence by, again for example, and amongst many others, the tiny house developed by a Hans Spiegel for the Deutschen Wohnungshilfswerke as emergency accommodation for those made homeless through allied bombing raids, and which reminds very much of the houses of the early 1920s Siedlerbewegung in Vienna, an interesting and informative moment in the (hi)story of architecture and spatial planning that began as an ad-hoc, do-it-yourself, housing movement before taking on an official status and seeing the likes of Adolf Loos, Josef Frank or Margarete Lihotzky, amongst others, participate in the design of houses, interiors and furniture. Or by Ernst Neufert’s so-called Hausbaumaschine [House Building Machine] from 1943, a ungainly looking proposition that allowed for a “mechanical casting of multi-storey buildings” and thereby “moves the construction of houses out of manual masonry and plastering”4, and which not only echoes the inter-War attempts to develop industrial construction methods and systems, we all remember, for example, a Mart Stam‘s 1924 demand that “the processing of building materials, which used to be done by the craftsmen, is now done faster and cheaper by the machine. However, construction itself has remained manual. This manual building process must make space for a new construction”5, but also very neatly predicts our contemporary 3D printing of buildings that, may, must, finally move “the construction of houses out of manual masonry and plastering”. Or Peter Koller’s plan for Stadt des KdF-Wagens that although it included the monumental the NSDAP required was, by all accounts, we haven’t studied it in detail, largely based on the 1933 Charter of Athens, that central document of Modernist urban planning, and a charter based to a large degree on the positions of Le Corbusier. Or by the early preference for the more village-esque urban form, a predilection which in many regards echoes the Garden City position/movement of the late 19th/early 20th century, and which, as noted, for example, from Garden Futures. Designing with Nature at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, was taken up with a goodly degree of gusto by the Modernists. Or Carl Burchard’s 1933 book Gutes und Böses in der Wohnung in Bild und Gegenbild [Good and Bad in the Home in Pictures] a work which while denouncing much of Modernism, including denouncing Marcel Breuer’s B 3 a.k.a Wassily Chair as resembling an execution chair, does demand and advance many of the principles of reduced, light, hygienic interiors that underscored so much Modernist thinking on the home, just in a more perceived national traditional, retrotopic, manner. While, and staying in the home, Power Space Violence presents an excellent example of a very literal use by the NSDAP leadership of International Functionalist Modernist positions, and of the hypocrisy so often associated with totalitarian dictators and/or populists of all hues, via a photo of Hitler reading a newspaper sat on a Thonet KS 46 steel tube cantilever chair 6, a work, apparently, as best we an ascertain, by Anton Lorenz, a work which not only features a ridiculously opulently angled backrest, a formal expression which, arguably, predicts Lorenz’s post-War upholstered TV recliners, but also shamelessly borrows the flowing curve of a Mies van der Rohe’s MR 10, a work that itself borrows shamelessly from Michael Thonet’s Nr. 1 Rocking Chair, thus in many regards bringing Thonet’s curve back to Thonet via the influence of Mies. And a photo that, aside from capturing Hitler in a steel tube cantilever, captures Hitler in a checked jacket and plus-fours: it looks like he’s off for a game of golf. Which, let’s be honest, we all wish he had done a lot more regularly.

Whereby one must add that the KS 46 wasn’t, as best we can ascertain, actually developed for the NSDAP, wasn’t an NSDAP commission, wasn’t developed for Berchtesgaden, was simply employed by Hitler at Berchtesgaden; an employment that helps underscore that our view of then from now is often far too simple, too well worn through repetition, too often travelled unthinkingly, without viewing the terrain we’re passing through and thereby the importance of exhibitions such as Power Space Violence that allow us all to question that which we unquestioningly accept, to see that which familiarity means we don’t see, and thereby, in context of Power Space Violence, allows one to approach more probable appreciations of the NSDAP and both their use of architecture, spatial planning and design and also their relationships with contemporary creatives.

Which brings us back to the gallery. And the context of Power Space Violence.

Part of the gallery of 150 architects, engineers etc, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

As noted above, while initially it very much resembles a Rouges’ Gallery, and one quickly identifies the many staunch national socialists and those opportunists who ignored reality, and the suffering of humanity, for personal gain, and one also recognises those who were either naive fools or felt they had no option but to work for the NSDAP, also includes the likes of, for example, Lothar Bolz, Fritz Selbmann, Kurt Liebknecht or Richard Paulick, individuals whose inclusion in the gallery we simply cannot comprehend: Bolz was a left-leaning lawyer who fled Germany in 1939 to Russia where he remained until 1947; Selbmann a communist politician who spent the greater part of the period 1933-1945 in a succession of concentration camps, including Waldheim, Sachsenhausen and Dachau; Liebknecht a left-leaning architect who spent the years 1931-1948 in Russia where, amongst other projects, he contributed to developing and realising Stalin’s extensive construction programme, that other great early 20th century totalitarian architecture and spatial planning moment; Paulick a socialist architect who fled to Shanghai in 1933 and where he remained until 1949/50. Why mix such individuals up with a group of committed Nazis, narcissistic hangers-on and asocial opportunists? Why? What statement is being made? What’s the take home? What’s one elucidating?

Whereby one must note that all four were very active after the War in context of construction, architecture and spatial planning in the DDR. Is that the point that’s being made? And if so, why? Where’s the relevance? We get the point that part of the project is about post-War continuation, which is important, but surely, surely, that must be a continuation that begins in and with the NSDAP dictatorship, a continuation rooted in the NSDAP dictatorship, not just a highlighting of those who were active in the DDR, regardless of any actual connection to and with the NSDAP dictatorship, to do that is to imply that the DDR dictatorship was but a continuation of the NSDAP dictatorship, which is a very olde worlde West German view of the Zonis, and which would be shocking if it were the intention, but which surely, surely, can’t be the intention. Surely? But, why else are Bolz, Selbmann, Liebknecht or Paulick highlighted? Power Space Violence is supposed to be about, as the sub-title tends to confirm, Planning and Building under National Socialism, not Planning and Building under the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, that’s a different exhibition, one that also very much needs to be staged, an exploration that very much needs to undertaken and a period that needs to be better popularly understood in terms of the relationships between architecture, spatial planning, state, community, identity, control etc, etc, etc, and where the roles and responsibilities of the innumerable protagonists need to be highlighted and discussed: but an exploration of Planning and Building under the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands that only has a relevance in context of Planning and Building under National Socialism where there are actual verifiable, tangible, navigable, links between the two exhibitions and not an “Oh look, that person favoured a perceived, romanticised, national tradition in their architecture”: you can’t denounce everyone who favours perceived, romanticised, national/regional traditional approaches as a Nazi, that’s not going to go down well in the CSU heartlands of rural Bayern or those great many other, primarily rural, locations in Germany where Modernists and their positions remain suspect and unwelcome, where life and architecture exist as the locals imagine it has since time immemorial. Nor go down well amongst the legions of Denkmalschützer, Building Preservationists, one of whose functions is to resist new approaches and anything that risks altering the visuals, and perceived inherent character, of any given region; but only very few of whom would identify as Nazis. And surely, surely, surely, one of the major take homes from Power Space Violence is that you can’t define anyone as either Communist or Nazi simply on their architectural predilections, Power Space Violence helping elucidate it’s a lot more complicated than that, admonishing unequivocally that we need to move on from such simplified compartmentalisation and view things more subjectively, from much wider, inter-disciplinary, perspectives and in their full complexity. Is Hitler freed from accusations of being a Nazi because he had a Thonet KS 46 at Berchtesgaden? Why introduce the likes of Bolz, Selbmann, Liebknecht or Paulick who had nothing to do with Planning and Building under National Socialism in a discussion on Planning and Building under National Socialism? You might as well bring in Schinkel, Persius and Stüler, those defining authors of Der Preussische Stil, the Prussian Style. Why associate the likes of Lothar Bolz, Fritz Selbmann, Kurt Liebknecht or Richard Paulick with the likes of Robert Ley, Fritz Todt, Hermann Giesler or Albert Speer?

Model of the planned Großen Halle for Berlin/Germania, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

In contrast, a Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, an Egon Eiermann7, a Wera Meyer-Waldeck, a Hans Scharoun, a Franz Ehrlich, amongst others, deserve to be, we’d even accept a Kurt Junghanns deserves to be, as does Lilly Reich, although she isn’t, because, and regardless of how personally committed they were or weren’t to the NSDAP’s politics and regardless of the degree to which, against their better judgement and/or political affiliations, they felt obliged through economic necessity, or other pressures, to take jobs with official bodies and/or official commissions, they did assist the NSDAP to varying degrees in the execution of their nefarious plans, and it is, we’d argue, right and important that (hi)story recalls that, not least by way of helping elucidate how any totalitarian/populist regime is dependent on the cooperation of a critical mass of individuals, and that even the smallest, least committed, cog plays a role in the operation, the operability, of the machinery. Totalitarian regimes, and populist, nationalistic, politics of all hues, aren’t possible if not enough of us contribute, and that contribution needn’t be openly supportive. There is no such thing as a passive role in a political system. Certainly not as an architect or spatial planner,

Which is another important take home from Power Space Violence.

One that helps underscore that for all that Power Space Violence is an exhibition about architecture and spatial planning, and Autobahnen, it is an exhibition that is only marginally interested in architecture, spatial planning and Autobahnen; much more Power Space Violence is an exhibition about, on the one hand, the infrastructure, organisation, laws and decrees that enabled the projects, that much fabled German Verwaltung, Administration, that, along with Autobahnen, so defines the nation’s Selfbild. And on the other hand is an exhibtion about the structures, systems, controls, terrorisation, oppression and warmongering inherent in and enabled by the projects, individually and in conjunction with one another: is an exhibition about architecture and spatial planning as political, social and cultural tools, about architecture and spatial planning as power and violence, about architecture and spatial planning as not just about form and material and statics and epochs.

And thus also an exhibtion not exclusively about the NSDAP.

The NSDAP were, sadly, not the only totalitarian dictatorship to plague society, past, present, and one fears, future; and a feature of all totalitarian regimes is, and invariably will be, their use of architecture and spatial planning as a means of controlling the population and securing their power. Nor indeed is architecture and spatial planning only socially and culturally relevant, political, when actively planned and employed as a tool of power and/or violence; all major architecture and spatial planning projects influence not just the visuals of any area but the behaviour of those who use it, define what is possible and is not possible, influence thoughts and actions, underscore dominance and subordination, prescribe inclusion and exclusion, control movement and interaction and perspective, reinforce positions and deny access to alternatives, etc, etc, etc, and that regardless of whether intended or not. Nor nor indeed are and were states the only bodies who employed and employ architecture and spatial planning as tools of power and control, be that directly or indirectly, one thinks, for example, of the design of office spaces as components of internal power and supervision structures or of the company towns of yore with their inherent total control over their inhabitants; and thereby one very naturally reflects on the fact that the likes of Google, Facebook or Elon Musk are currently developing their own contemporary, invariably networked, smart, versions of company towns. What could possibly go wrong?

Yet all too infrequently are architecture and spatial planning considered beyond the visuals. All too infrequently are architecture and spatial planning considered beyond the architects pronunciations on their vision, or the politicians pronunciations on their vision. A narrow view of architecture and spatial planning Power Space Violence very much warns against and demands we move on from. Power Space Violence through helping one approach better appreciations of how the NSDAP used architecture and spatial planning to control and order and oppress and undermine communities and societies and individuals, and also to approach better appreciations of how the architectural and spatial planning projects of the NSDAP formed the contemporary society of the period, provides very instructive insights of architecture and spatial planning beyond form and material and statics and epochs that can allow us to develop better structures and systems and processes for developing our built environments, and for all, and arguably most importantly, can help develop a popular appreciation that architecture and spatial planning are important, key, components of how any society is formed and develops. And therefore subjects for us all.

An early working title for the exhibition was Mehr als Speer, More than Speer, a title which, amongst other interpretations, allows one access to appreciations that for all that Albert Speer was central to the NSDAP’s architectural and spatial planning policy, that policy and its realisation was the work of more than just one man, and was about lot more than architecture and spatial planning.

As an exhibition Power Space Violence very much mediates that message; allowing as it does not only access to the great many architects, engineers et al who contributed to the many programmes, and also highlighting the role civil society, the German population, played in assisting those programmes, but also very neatly moving the discussion beyond architectural and spatial planning and into the contexts in which that architecture and spatial planning occurred, and the role architectural and spatial planning played in the NSDAP dictatorship and in supporting the pursuit of their nefarious ambitions. And also very neatly moves the discussion outwith Germany with brief glances to contemporaneous architectural and spatial planning developments in, for example Italy, Russia or America, including Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1938 plans for an Autobahn network in America; an international comparison that is important in better approaching the NSDAP in context of the period.

And also allowing one to better appreciate that the much vaunted representation of NSDAP architecture and spatial planning wasn’t always representation through the scale and pomp of the Nürnberg Reichsparteigelände or the plans for Germania, and also to better appreciate that representation through scale and pomp wasn’t always the most important representative function of the NSDAP’s architecture and spatial planning; but more often, and often more important, is and was representation as how the projects expressed and guided the NSDAP’s aims and positions and/or how they helped the NSDAP secure and reinforce their power, be that via, for example, collective/communal living solutions, the building of new towns both within the official German borders and also in the occupied regions, or the zoning of cities, whereby in context of the latter the discussion on ghettoes graphically underscoring that the ghettoes were a spatial planning project as any other, just infinitely brutal and inhumane. And thereby helps reinforce that architecture and spatial planning is never, ever, a passive art.

If, as noted above, the scale and scope of the project, and its presentation in the AdK, mean it can be but an introduction, can be but a start to more detailed research on your own. And for all a start to developing better, more probable, appreciations of the myriad, complex, relationships between architecture, spatial planning, state, community, identity, control etc, etc, etc. And a start to learning to better formulate questions on the role and function of architecture and spatial planning in any society or community.

Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism is scheduled to run at the Akademie der Künste, Pariser Platz 4, 10117 Berlin until Sunday July 16th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme can be found at www.adk.de/power_space_violence

In addition a richly illustarated catalogue featuring 8 essays is available in German and English.

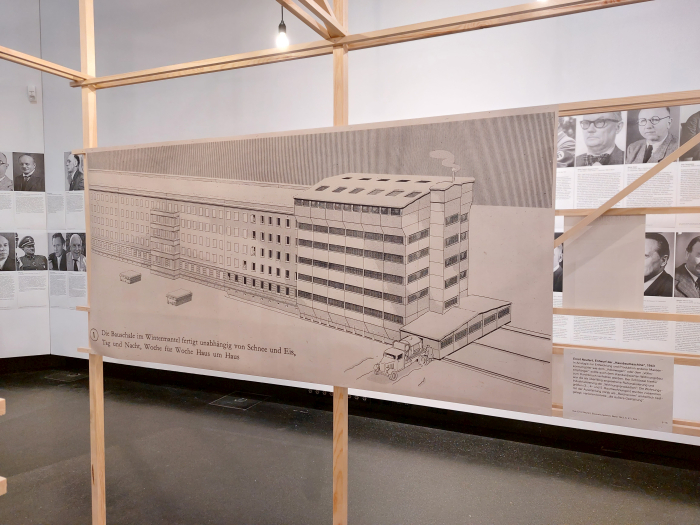

An illustration of Ernst Neufert’s proposed Hausbaumaschine, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

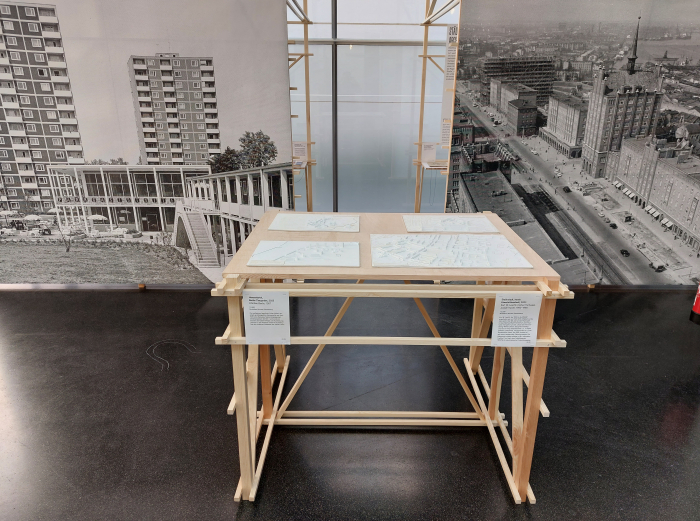

Post-War East and West Germany as represented by Neue Heimat estate in München-Bogenhausen (photo l) and the Hansaviertel Berlin (model l) juxtaposed with Rostock (photo r) and Eisenhüttenstadt (model r), as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

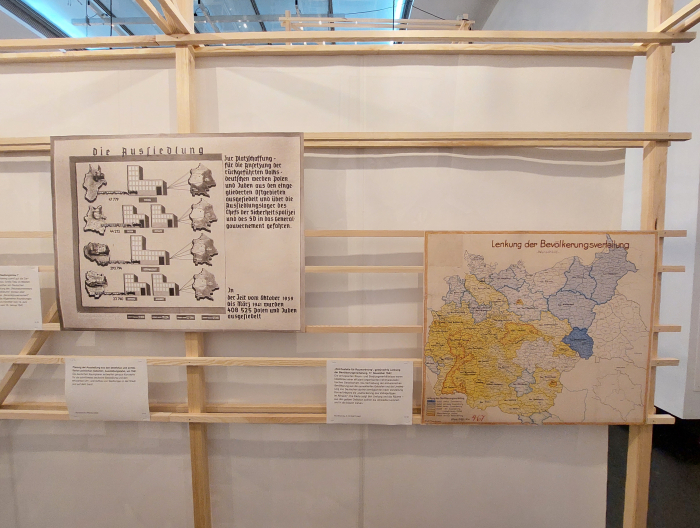

Maps and facts relating to deportations and forced migration in and from Poland, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

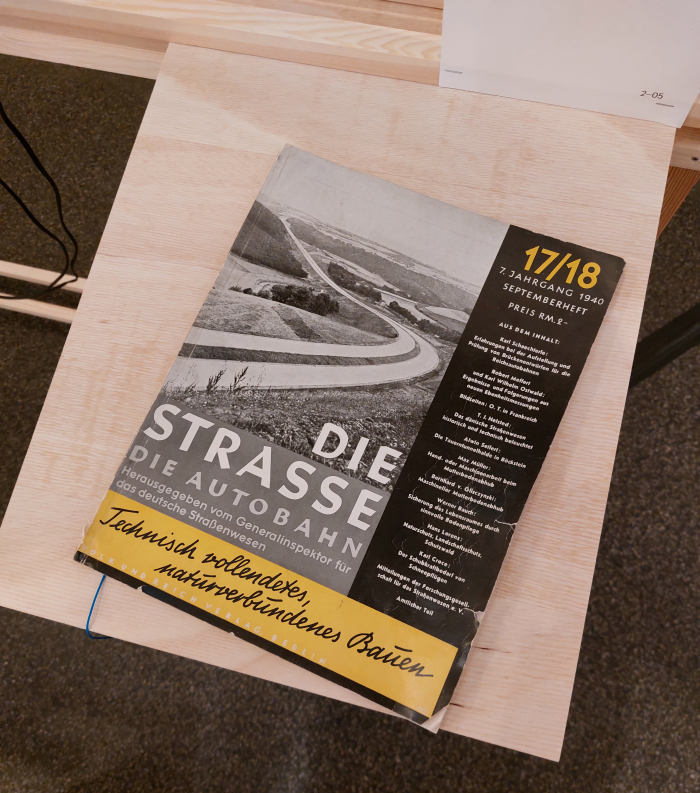

September 1940 edition of Die Straße. Die Autobahn, one notes a publication in its 7th volume….the NSDAP loved their Autobahnen, as seen at Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

1. In the interest of completion, when the project was commissioned the Ministry was formally the Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit, today its the Bundesministerium für Wohnen, Stadtentwicklung und Bauwesen.

2. The project is officially divided into seven themes, but for us the exhibition, on account of its design, is in five chapters. It’s not an important point, but one we felt a need to make…….

3. see Franz Schulze & Edward Windhorst, Mies van der Rohe. A critical biography, new and revised edition, The University of Chicago Press, 2012, page 169/170

4. Ernst Neufert, Bauordnungslehre, Volk und Reich Verlag, Berlin 1943 page 471

5. Mart Stam, Modernes Bauen 1, ABC Beiträge zum Bauen 2 1924

6. The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek is in possession of (at least) three photos of Hitler in his KS 46, all lightly pixelated, one presumes because Hitler is in them, but you can get the idea, although in one photo there is side table we’re very keen to see in more detail…. For reasons best known to themselves the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Bildarchiv employs time limited session IDs for searches as such direct links to search results aren’t possible, however visit https://bildarchiv.bsb-muenchen.de and search for KS 46

7. We very obviously are in no position to argue against the curators, technically we’re in no position to even to begin to consider the possibility of potentially forming an argument against the curators… that said, when they note in context of Egon Eiermann and Hans Sharoun that in their 1930s works they tried “to continue the “Neue Bauen” of the Weimar Republic in varied forms”, we get a little bit itchy. Or at least we do in the case of Eiermann, with Sharoun we’re happy to accept by way of an argument that the so-called Haus Baensch he realised in 1934/35 in Berlin-Spandau does feature several formal elements that are more Kochenhofsiedlung than Weissenhof, where Sharoun realised a very similar work to Haus Baensch with much more quadratic elements, and certainly a much flatter roof. But with Eiermann, we’d argue, that before he built Haus Matthies, Potsdam, in 1937 that project presented in Power Space Violence by way of the curators argument, all his houses had been relatively traditional, certainly gable ends and pointy roofs are very prevalent, as is brick and stone, and that not because of any kowtowing to or fitting in with the NSDAP but because he was at the start of his career and still finding his feet. And only post-War did he begin to embrace more Modernist informed positions and find his own voice. We’ll come back to the subject later, because it is interesting and important. Just wanted to formally register our objection here…….

Tagged with: Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Planning and Building under National Socialism, Power Space Violence