Plastic Material − Magic Material: Freedom and Limits of Design at the HfG-Archiv, Ulm

Arising in the early 1950s from a collective, a community, who had been ardently opposed to the NSDAP, their world view and their warmongering dictatorship, the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm understood itself very much in context of the post-War re-development of society, the post-War development of a new democratic, future-resilient, society. In West Germany and further afield.

Thus it is little wonder that synthetic plastics, that material class which post-War offered, embodied, (seductively, unscrupulously) foretold, the promise of a borderless democracy, an egalitarian global society, should have been a material of experimentation and utilisation at the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm.

With Plastic Material − Magic Material: Freedom and Limits of Design the HfG-Archiv, Ulm, reflect on synthetic plastics in context of the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm. And also in context of society and democracy…….

The origins of Plastic Material − Magic Material: Freedom and Limits of Design are to be found less in considerations on the (hi)story of synthetic plastics in context of West Germany, nor in any an archival discovery concerning synthetic plastics and the Hochschule für Gestaltung, HfG, Ulm, but primarily in a piece of blue plastic netting that Christiane Wachsmann, the HfG-Archiv’s long serving archivist, Deputy Director and curator of Plastic Material − Magic Material, found by chance in a field. Much as one has long found by chance in fields fragments of porcelain or glass or metal as artefacts of communities and societies past. Now one finds synthetic plastic waste as artefacts of our contemporary communities and societies. Synthetic plastic waste future generations will continue to find, because, as with porcelain or glass or metal, synthetic plastics don’t vanish, despite Gaetano Pesce’s claim in context of the 1972 MoMA New York exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape that in the year 3000 “all the structures in wood, ABS plastic, melamine, polyurethane, etc”, from the year 2000, “have been irreparably lost or damaged by heat and humidity.”1

No Gaetano, sorry, there will still be pieces of blue plastic netting.

Blue plastic netting that allows access to considerations on both the advantages of synthetic plastics and the problems of synthetic plastics, much as the reconstructed gondola from the first Zeppelin displayed in Into the Deep. Mines of the Future at the Zeppelin Museum, Friedrichshafen, allowed and allows access to considerations on the advantages and the problems of aluminium, that, as opined from Friedrichshafen, other defining material of the 20th century.

And a piece of blue plastic netting with which Plastic Material − Magic Material opens, alongside further examples of the sorts of discarded, immortal, synthetic plastic artefacts of our contemporary industrial society one can, and does, often come across by chance when out and about, and which future generations will continue to find while out and about, including, for example, a bottle top, a cable tie or a leg from a pair of glasses, itself a nice reminder of how synthetic plastics have positively contributed to the development of global society, have (at least in part) justified the promise bore in them, before moving on to briefly explore both the post-War establishment of synthetic plastics in (West German) society, and also, and with a slight (and in certain conservative circles ongoing) lag, the rise of appreciations of the problems of synthetic plastics. And finally arriving at the HfG Ulm.

Blue plastic netting and other artefacts found in fields and on the streets, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

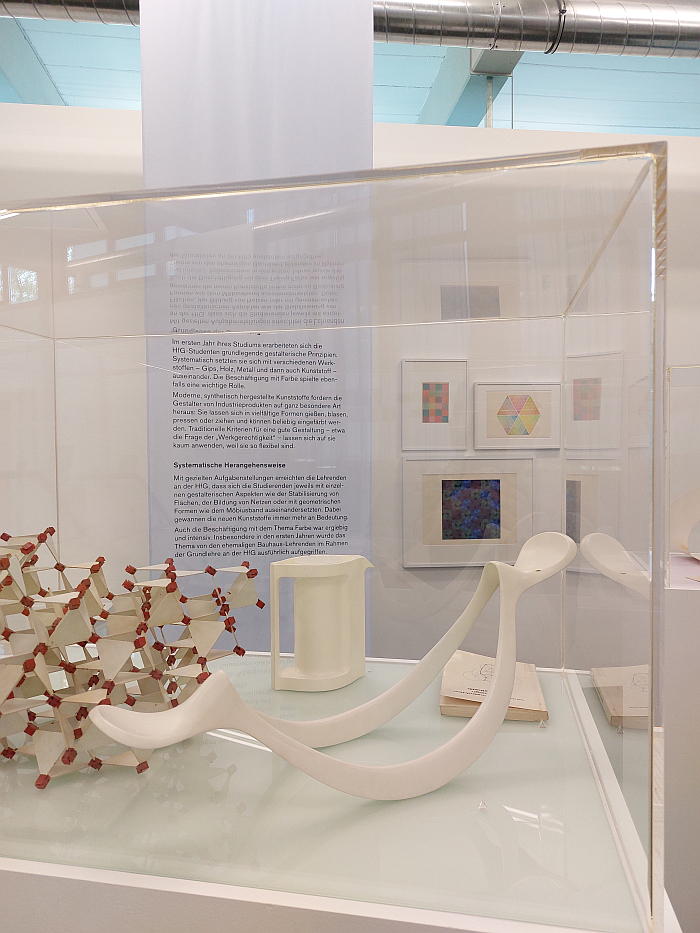

As Plastic Material − Magic Material notes, although the founders of the HfG Ulm planned and envisaged a plastics workshop, the college was initially only equipped with more traditional material workshops, including the carpentry workshop and metalwork workshop that were so important for the development, and production, of the Ulmer Hocker, that Ulmer Idea, Icon, Idol, that reminder that wood can also be a very democratic material, and it wasn’t until 1958, some five years after teaching began, and two years after the completion of the HfG building, that the plastics workshop was initiated.

Established with the help of BASF, a leading protagonist of the expansion, pun intended, of synthetic plastics in post-War West Germany, and a company who alongside the likes of Braun or Pfaff were an important industrial partner for, and sponsor and supporter of, the HfG Ulm, the plastics workshop was developed, and initially led, by Cornelius Uittenhout, a creative about whom only very little is publicly known, other than he was a Dutch master silversmith who in 1954 took on responsibility for the fine metal workshop at the HfG before being tasked with the plastics workshop; and thus the biography of a silversmith applying their skills and approaches and positions to plastics which echoes very nicely, and very, very, satisfyingly, with that of Christian Dell, a German master silversmith who from 1922 to 1925 had served as the Werkmeister, that technical counterpart to the more artistically orientated Formmeister, in the metal workshop at Bauhaus Weimar, and who in the 1930s developed a wide range of products, from the various and varied novel synthetic plastics of the period, for Spremberg based Römmler AG, and thereby, we argue, we insist, making Christian Dell the world’s very first plasticsmith. An honour arising (largely) because in the early decades of synthetic plastics’ rise to mass popularity the questions of how to work with them weren’t that well understood, were difficult to formulate, was something that had to be discovered, learned; a process for which two long standing professions are and were very much the obvious ones to turn to: the potter/ceramicist and the silversmith.

Similarly, as Plastic Material − Magic Material helps elucidate, when the plastics workshop at the HfG Ulm opened there were, despite the two and half decades extra experience since Dell arrived in Spremberg, a lot of unanswered questions to be explored; questions approached at the HfG Ulm not only by the silversmith Uittenhout but also by Otto Schild, a trained porcelain modeller and ceramicist who after a period working with Wilhelm Wagenfeld at the Technischen Hochschule, Stuttgart, had taken charge of the plaster workshop at the HfG Ulm. And were also approached by Walter Zeischegg, an Austrian sculptor who brought his artist’s view and approach to product design, rather than the craft view of a potter/ceramicist or silversmith; and who in doing so was, as Plastic Material − Magic Material explains, of fundamental importance to the development of plastics at the HfG Ulm, where his largely conceptual sensibilities allowed for alternative insights into not only what synthetic plastics were but what they were capable of. Helped release that inherent power novel materials possess to enable and bring forth novel objects, concepts, relationships, realities, et al.

A conceptual rather than rational approach to product design that can be instantly appreciated in Zeischegg’s late 1960s stacking ashtray for Helit, a work derived from considerations on what happens when a sine wave is forced to follow a circular path, considerations no technician nor scientist could conceive, considerations that synthetic plastics are ideally situated to allow one to undertake in physical manifestations rather than in theoretical reflections, and which as such help underscore both the new possibilities plastics brought with them, and also that those new possibilities had to be understood to be exploited. And an approach that can appreciated in its fuller expression in Plastic Material − Magic Material thanks to the varied and various formal studies by Zeischegg, and his contemporaries at the HfG Ulm, and the access they allow to appreciations of how Zeischegg approached synthetic plastics, how Zeischegg sought to understand the possibilities of novel synthetic plastics, how Zeischegg explored the borders of what plastics were capable of. And also by a stupidly simple modular bowl system which, as with the ashtray, delightfully, deliciously, abstracts a sine wave into a functional object that can’t be imagined, can only be arrived at.

The stacking sine wave ashtray by Walter Zeischegg through Helit, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

Not that the (hi)story of synthetic plastics at the HfG Ulm is one exclusively of the re-imagined sine waves and the inconceivable free forms of a Walter Zeischegg, it’s not, for as Plastic Material − Magic Material elegantly elucidates the HfG Ulm also employed plastics for objects, shapes and forms existent and familiar in other materials, including for kitchen equipment, power tools, audio-visual equipment and for the anonymous grey quadratic boxes a Luigi Colani so aggressively, and so inaccurately, accuses the HfG Ulm of concentrating on, and about which a Lucius Burckhardt is also so disparaging2, uniting Burckhardt and Colani being a rare trick that, arguably, only the HfG Ulm can achieve, and which in doing so highlights the fundamental differences between the positions of the two. And synthetic plastics also employed for cars; specifically a so-called Delta 6 developed in the late 1960s by Detlef Unger, Henner Werner & Michael Conrad as a low-cost modular vehicle concept based around a plastic floor assembly; and thus a West German plastic car developed but a decade or so after the East German Trabant. Yet whereas in the East the Trabant was serially produced, in the West the Delta 6 failed to find a producer. Or at least a direct producer; indirectly it served as the model for innumerable Playmobil cars. Which is a comparison well worth reflecting on.

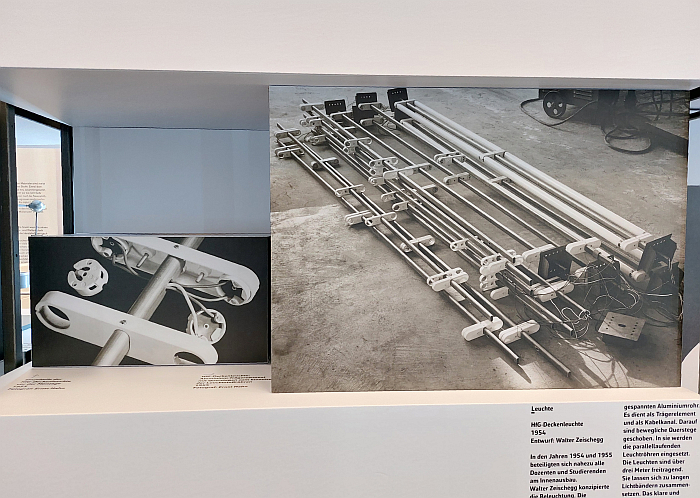

Nor only was Walter Zeischegg exclusively curves and waves and experimental forms; as can be seen in the HfG-Archiv’s permanent exhibition Zeischegg was also responsible for the development of the ceiling lighting in the HfG Ulm, a lighting system based around a small, unassuming, rationally formed, plastic connecting unit which enables the naked lighting tubes to span the three metres between the trusses of the repeating structural units into which they are anchored; a lighting system by Walter Zeischegg still in use and which makes taking photos of vitrine exhibitions such as Plastic Material − Magic Material exceedingly difficult, but then that probably wasn’t a consideration at the forefront of Walter Zeischegg’s thoughts. Wish it had been though. And lighting connectors that are just one of innumerable plastic objects, one of innumerable uses of plastics, innumerable considerations on and proposals for plastic’s place in the coming society, to be found in the HfG-Archiv’s permanent exhibtion, including, for example, a modular bus stop shelter concept, seating units for the wagons for the Hamburger Hochbahn or in context of research into ergonomic knife handles; innumerable objects, proposals and positions in the permanent exhibition which help reinforce the importance of synthetic plastics in the (hi)story of the HfG Ulm, reinforce the importance of the HfG Ulm the (hi)story of synthetic plastics and which in doing so compliment and, pun again intended, expand that presented and discussed in Plastic Material − Magic Material.

A Delta 6 by Detlef Unger, Henner Werner & Michael Conrad, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

An expansion and complimenting also undertaken by the most pleasing manner in which Plastic Material − Magic Material effortlessly moves beyond its primary focus on synthetic plastics and the HfG Ulm.

Including into a discussion on colours; a not irrelevant extension for, on the one hand, amongst the early advocates for, early pushers of, synthetic plastics, certainly in the West German context in which Plastic Material − Magic Material largely exists, were companies with (hi)stories in the manufacture of colour, including, for example, the aforementioned BASF. Thoughts which remind us all that that is what plastics often are: solid colours in a readily utilisable form to enable the creation of coloured objects, rather than liquid colour to be applied to an object. Which also reminds us all that although in the 1930s a Christian Dell could and did produce coloured objects for Römmler, his options were much more limited, and associated with much more cost and effort, than the near infinite possibilities the post-War novel materials allowed the post-War plasticsmiths, thus opening considerations on questions of the relationships between the popular post-War rise of plastics and the colour they brought with them to post-War society. Which further reminds us all that Verner Panton’s two late 1960s Visiona projects were commissions from and for Bayer, another Germanic colour manufacturer who post-War were seeking to grasp, exploit, the possibilities of synthetic plastics, for all in context of textiles and furnishings, and whose chosen conduit, certainly in the late 1960s and into the 1970s, was the array of colour available.

And on the other hand because an important aspect of the career of Otl Aicher, that so important, and popularly defining, HfG Ulm protagonist, was concerned with colour, including his development in the early 1960s of a so-called Colorthek for BASF, essentially a colour palette by way of tackling the problems caused by the aforementioned near infiniteness of hues in which post-War synthetic plastics could be produced, an, if one so will, start of the standardisation and organisation of plastic colours by way of making the new materials more profitable for the manufacturers through limiting what the customer could have. A, again if one so will, expression of the need to define the Freedom and Limits of the exhibition title in context of commercial availability of synthetic plastics, and which in being such helps underscore the function of standardisation and organisation of naturally occurring variability in industrial societies, a theme also touched upon in Plant Fever. Towards a Phyto-centred design at Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden. And a Colorthek which in its variations on grey, and thus its contrast to the vibrancy of the Weimar Bauhaus, indicates that a Luigi Colani wasn’t completely wrong and also offers access to some interesting considerations on the place and function of colour not only at the HfG Ulm but in 1960s West Germany. And for all considerations on the place and function of the HfG Ulm in the colours of 1960s West Germany; considerations aided and abetted by a Verner Panton’s observation in his 1997 book Lidt om Farver/Notes on Colour that, “for many years Braun confined itself to colours like white and black and, as a merry prank, grey”, before, and as discussed from Braun 100 at the Bröhan-Museum, Berlin, in the 1970s Braun experimented with reds, greens, oranges et al. An experimentation that although (at the behest of Dieter Rams was) short-lived, very notably began after the closure of the HfG Ulm. In how far that is an actual connection rather than an amusing coincidence, in how far the standardisation and organisation of plastic colours by the HfG Ulm delayed the explosion of colour in post-War West Germany, and the wider influence of the HfG Ulm on the colourscope of 1960s West Germany being subjects worthy of further exploration.

Plastics were also experimented with in the HfG Ulm architecture department, here as a novel roofing system, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

And also expands into definitions of plastics, with a little aid from German compound nouns. And Dr. Jens Soentgen. For while the English “plastic” has become the globally employed term for the wide-range of synthetic materials the chemical industry began producing in the early 20th century, the more technically correct German term is Kunststoff; a word that, and as with so many German compound nouns, offers interesting and informative alternative approaches to concepts and positions. Kunststoff = Kunst + Stoff: the latter being readily translated as material, the former as art/artistic, but also as man-made, artificial, and, as Jens Soentgen argues3, all materials that human society derives from naturally occurring materials and subsequently employs should, must, be considered as Kunststoff, i.e an artificial, man-made material, including the porcelain, glass and metal of previous communities and societies which we have long found by chance in fields and which are now joined by the synthetic materials of the 20th century, by the Kunststoff of the 20th century.

A position which not only allows one to appreciate that finding fragments of plastics in fields is in many regards to be expected, they are in essence no different in terms of their provenance from porcelain or glass or metal, but also allows for differentiated perspectives on the place of synthetic plastics in the (hi)story of human civilisation, allows one to understand the Plastics Age as being as valid an epoch as the Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, etc, or the Aluminium Age that arose ever so slightly before the Plastics Age, and which in doing so also allows for reflections and considerations on our relationships with all materials, including on the reality that all novel materials, all novel Kunststoffe, bring with them advantages and problems, that they always have and always will — the novel biological based Kunststoffe being developed as alternatives to contemporary chemical based Kunststoffe, and as discussed in, for example, Plastic: Remaking Our World at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, will bring forth problems once fully integrated into industrial processes — and which thereby helps focus ones attention on the Freedom and Limits of the exhibition title, that necessary, important, balance to be found between what is possible with novel materials, that borderless forming of synthetic plastics a Walter Zeischegg played so engagingly with, or the lightness aluminium enabled in aircraft of all genres, and the damage that novel materials invariably bring with them. And thus helps shift the focus from the Material of the exhibition title to the Design; is an admonishment of the responsibility of designers to be aware of where not only any individual project stands between advantage and problem, but where the planet is and how far we can exploit the advantages of any novel Kunststoff without allowing the inherent, if often unknown, problems to become dominant.

Examples of post-War plastic objects, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

Considerations aided and abetted in Plastic Material − Magic Material by the brief reflections offered on definitions of sustainability, and for all the highlighting that sustainability is also a formal criteria: the planned visual obsolescence of objects so beloved of the clothing industry, and gladly taken up by industrialists of all hues by way of increasing their profits, inevitably leading to an irresponsible unsustainably.4 A reality Plastic Material − Magic Material argues, and perhaps not unsurprisingly argues, can be counteracted by gute Form, that search for a form which in its concentrated focus on functionality is resistant to the forced fashions and fads of commerce and consumerism, a position which was propagated with such zeal by the HfG Ulm’s founding rector Max Bill and which can be understood in so many HfG Ulm works, including in Walter Zeischegg’s stacking ashtray, a work that formally is as engaging and alluring, and gut, as it ever was, and which similarly has lost nothing in terms of functionality over the decades. If the decline in smoking since the late 1960s does mean it stands a little as an anachronism in the 2020s. Which, yes, is an interesting starting point for reflections on the much vaunted, and lazily marketed, idea of “timelessness” in product design.

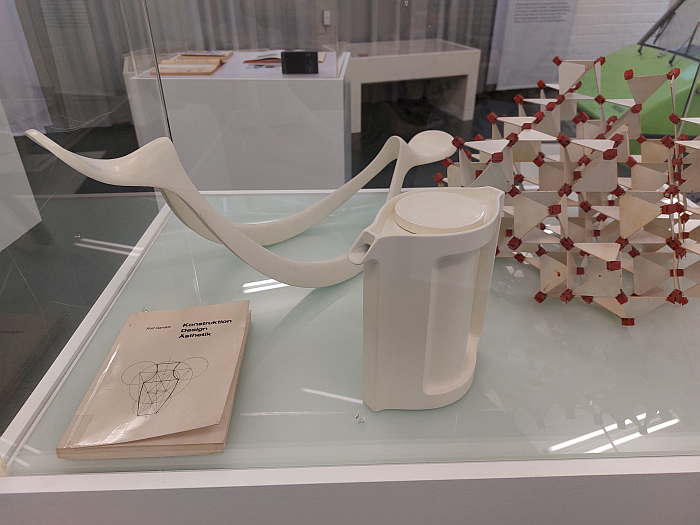

Reflections on gute Form further extended by the brief discussion on a jug developed by Rolf Garnisch according to the positions of the philosopher Max Bense that the perfect form can be calculated, derived, from a set of a criteria, an ultra-rational approach to product design which is not only interesting in itself, but very interesting to consider in context of the future place of AI in product design. And an ultra-rational jug juxtaposed in Plastic Material − Magic Material with a see-saw developed by Peter Hofmeister on the basis of observations of nature, on the application of natural forms, via Mimesis, an approach favoured, perhaps not unsurprisingly, by Walter Zeischegg. And thus a juxtaposition between the objectivity and rationale of science/engineering and the subjectivity and emotion of art, that allows access to appreciations that, and despite how it is often presented, the HfG Ulm wasn’t a position on product design but was a discourse on product design. A remains a very valid component of an ongoing discourse.

And considerations on freedoms and limits also aided and abetted via a presentation of three projects by students at the HfG Schwäbisch Gmünd, a not irrelevant choice for, as oft opined in these dispatches, the HfG Schwäbisch Gmünd can, in many regards, be considered the official unofficial successor institute of the HfG Ulm, being as it is that HfG where a great many Ulmer landed when their HfG closed in 1968, an Ulmer influence that, arguably, can still be felt in the corridors of Schwäbisch Gmünd today. And also a Schwäbisch Gmünd, if not a HfG, where Cornelius Uittenhout completed his Meister studies. Three HfG Schwäbisch Gmünd projects which, amongst other themes, concern themselves with novel materials, with novel Kunststoffe, as replacements for synthetic plastics, including Trebodur a Kunstsstoff developed by Niko Stoll & Tillmann Schrempf from the spent grain that arises in the brewing process, a waste product often used as livestock feed but which, as Niko & Tillmann elegantly demonstrate, can also be formed into a material which can serve as the basis for, amongst other objects, a novel packaging system for beer cans, an alternative to the plastic rings commonly employed. A novel beer can packaging system that not only untold numbers of ducks and swans would be thankful for, removing as it does the risk of becoming trapped in a discarded piece of synthetic plastic, but which also brings one back to the blue plastic netting that inspired Plastic Material − Magic Material and its reinforcement, its embodiment, of the appreciation that whereas the problems associated with previous communities’ and societies’ novel Kunststoffe are and were primarily associated with their extraction and processing — the Bronze Age inarguably brought with it problems akin to the Aluminium Age, just at much, much lower, and more localised, levels — the problems associated with contemporary synthetic plastics are, in addition to those associated with their extraction and processing, associated with the after-life of the products we form from them: in comparison to a fragment of blue plastic netting lying in a field or a river, a fragment of porcelain or glass or metal does but little harm. Unless you stand you on it with bare feet. And thereby allowing access to appreciations that our contemporary plastics problem isn’t, it is a contemporary social problem, a problem with and in contemporary society. Or put another way, if we as a species were able to deal responsibly with plastic beer packaging ducks and swans would have nothing to fear, but we can’t. So they do.

Thoughts which allow Plastic Material − Magic Material to underscore that not only the possibilities of novel materials, novel Kunststoffe, need to be explored in order to be understood, but also the dangers; the limits need to be learned and appreciated just as much as the freedoms. And that not just by designers, but by us all, collectively and individually. Something that it is all too easy to forget in the flurry of that first flush of excitement when exploring the novel, be that novel materials, novel technology, novel transportation, novel communication, etc, but which we all really, really, should try to remember. We’ve certainly had enough lessons.

Trebodur as beer packaging system, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

An accessible and well-paced showcase, if by necessity of the spatial realities of the HfG-Archiv bijou in scale, if not in scope, it’s a wide-ranging presentation which approaches it narrative from a variety of perspectives and via a very pleasingly expansive, yes pun, mix of objects, Plastic Material − Magic Material offers, on the one hand, access to differentiated perspectives on the HfG Ulm, very intelligently uses synthetic plastics as a conduit via which to approach the HfG Ulm from a wider range of inter-connecting perspectives than are normally enabled: to approach, for example, the HfG Ulm as a place of experimentation and research as much of teaching, on the HfG Ulm as a place of emotive art as much as rational design, as more than just a Hans Gugelot and an Otl Aicher, on the HfG Ulm as a partner, an important and informative partner, of West German industry in the earliest post-War decades and the processes of physical, social, culture, economic, et al re-building. And also helps underscore that for all the HfG Ulm is popularly understood as the official unofficial Bauhaus successor it was not only an institution very much with its own attitude and understanding of itself but also an institution very much at the heart of 1950s and 1960s West German society and economics; was an institution concerned with the question of contemporaneousness and future-resilience that was also a concern at Bauhaus, but in a 1950s/60s context not a 1920s/30s context; wasn’t about the disingenuous mimicking revivalism that defines contemporary understandings of Bauhaus in the 21st century. And thereby offers access to alternative perspectives on the Bauhauses, what they were and what they are.

And as a showcase Plastic Material − Magic Material also offers access to alternative perspectives on the post-War (hi)story of synthetic plastics, primarily in a West German context but readily extendable into wider global contexts, and for all, reminds of the responsibilities that come with all novel materials. With all novelties.

Responsibilities Plastic Material − Magic Material reminds us also come with the democracy that in the early 1950s was so effortlessly embodied by synthetic plastics and which synthetic plastics (seductively, unscrupulously) promised; Plastic Material − Magic Material is a timeous, and apposite, reminder that with democracy as with the novel there is always an element of responsibility, individual and collective, that the basis of the freedoms promised by the novel or by democracy is accepting those responsibilities.5 That for all that democracy, as with synthetic plastics, is magic in the sense of enchanting, bewitching or fascinating, both are also magic in sense of expertise, ability or adeptness, are talents to be continually worked at.

And if we lose sight of that, and negate our responsibilities, collectively and individually, that which appears to be offer a borderless bountiful freedom can quickly become an oppressive, toxic, limitation. There is, as synthetic plastics teach us, but a very, very fine line between magic and curse.

Plastic Material − Magic Material: Freedom and Limits of Design is scheduled to run at the HfG-Archiv, Am Hochsträß 8, 89081 Ulm until Sunday January 7th

Full details can be found at https://hfg-archiv.museumulm.de/

In addition a, sadly, German only, catalogue featuring numerous essays around the themes involved is available.

A see-saw concept by Peter Hofmeister, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

Stacking bowls by Otto Schild (l) and a coffee service by Cornelius Uittenhout, as seen at Plastic Material – Magic Material, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG-Archiv, Ulm

1. Gaetano Pesce in Emilio Ambasz [Ed.], Italy: the new domestic landscape achievements and problems of Italian design, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1972 page 215

2. Although Lucius Burckhardt cooperated with, and briefly taught at, the HfG Ulm he was openly critical of not only much of what was done but also of the concept of gute Design, see Lucius Burckhardt, Design is unischtbar. Entwurf, Gessellschaft & Pädagogik, Martin Schmitz Verlag, 2012 for a number of texts explaining his positions.

3. In addition to Jens Soentgen’s various publication on the theme there is a chapter in the exhibition catalogue explaining his position.

4. In context of planned visual obsolescence we can always recommend Vance Packard’s 1960 book The Waste Makers which as a work written in the late 1950s offers a contemporaneous view on the earliest days of planned visual obsolescence as a marketing tool, rather than being a historic reflection imbued with our decades of experience and thus is particularly interesting and informative.

5. Yes, we are very deliberately juxtaposing freedom and responsibility rather than the freedom and limits of the title: considerations on limits to and of democracy are, while valid and important considerations, way beyond the scope of the subject at hand and not a path we’re keen to go down today. But, obviously, feel free to explore it yourselves.

Tagged with: BASF, Cornelius Uittenhout, Freedom and Limits of Design, HfG Ulm, HfG-Archiv, plastic, Plastic Material − Magic Material, Ulm, Walter Zeischegg