smow Blog Design Calendar: May 25th 1895 – Happy Birthday Clara Porset!

“¿Qué es diseño?” asked Clara Porset in 1949. What is design?1

Not because she didn’t know. Far from it. Over the course of the preceding two decades Clara Porset had ably demonstrated her considered, critical and responsive understandings of design; understandings that saw her develop into one of the most important, interesting and informative furniture designers in Mexico, understandings that saw her develop into one of the more important, interesting and informative protagonists in the development of industrial design in Mexico.

Before she slipped from view and into the (relative) anonymity she finds herself today.

Before the more pertinent question became, ¿quién es Clara Porset?

Clara Porset (1895 – 1981) (Photo commons.wikimedia.org CC BY-SA 4.0, courtesy Archivo Clara Porset Dumas)

Born in Matanzas, Cuba, on May 25th 1895 as the scion of a wealthy Spanish family, Clara María del Carmen Magdalena Porset y Dumas was primarily educated in America, including undertaking courses at the New York School of Interior Decoration and Columbia University’s School of Fine Arts before in 1928 she travelled to Paris to work with/study under the architect and designer Henri Rapin, the same Henri Rapin Charlotte Perriand had worked with/studied under in the first half of the 1920s. And not the last time Porset and Perriand’s paths would cross, at least virtually.2 In addition to working with/studying under Rapin, Porset also used her time in Paris to take courses at the Sorbonne, Louvre and École des Beaux Arts, to travel extensively within Europe and to serve as the Paris fashion correspondent, the Paris style correspondent, for the Cuban magazine Social3, a magazine whose urbane, cosmopolitan, wealthy readership helps underscore that the Social of the title was very much in context of Social-ite, Social-life, Sociali-ising and not Social Responsibility, Social Equality.

Despite the very classic nature of the studies Porset, one presumes, undertook at the Sorbonne, Louvre and École des Beaux Art, the developing avant-garde of late 1920s Europe clearly didn’t pass her by, and clearly struck a chord, for following her return to Cuba4 Porset became an ardent advocate of Modernist design thinking5: an advocacy undertaken through the various public and private interior and furniture design commissions she acquired through the design studio she established in 1930 in downtown Habana; through her lectures and public talks, including one in May 1931 titled, Contemporary interior decorating: Its adaptation in Cuba, and in which she refers, approvingly, to Adolf Loos and his views on ornamentation. And also through her regular articles in Social: in January 1930 Porset swapped her role as Parisian fashion correspondent for that of interior and furniture design correspondent, her first article focussing on the French architect and designer Robert Mallet Stevens and over the next two years she introduced Social‘s urbane, cosmopolitan, wealthy, readership to names such as John Vassos, Le Corbusier or Ivan da Silva Bruhn and subjects such unadorned, quadratic Functionalist Modernist architecture, to new concepts for the interior design of retail spaces, or to Muebles de Metal, and also taking readers to the 1930 Stockholm exhibition, the 1930 Triennale di Monza, and the 1930 Salon des Artistes Decorateurs, Paris. A trio of exhibitions covered in one very short text, one ridiculously short text when one considers where she had been, and which ends with the reflection that “….in its purely artistic aspects, the new spirit appeals only to a minority, but in its social aspect it is logical that it demands general interest and subsequent approval”.6 A statement which stands very much opposed to the -ite, -life, -ising understandings of social inherent in Social, but very succinctly indicates where Porset’s interest in Modernist ideas was to be found. And while (we can all safely presume) Porset belonged to the minority in 1930’s Cuba who approved of the Modernists’ formal expressions, that would evolve.

In 1932 her participation in protests against the, then, Cuban President Gerardo Machado saw Porset flee to New York, returning to Habana in 1933 following Machado’s (abrupt) departure, and where she continued running her design studio, took up a teaching position at the Rosalía Abreu Foundation Technical School for Women, and wrote to Walter Gropius to enquire about the possibility of joining Bauhaus; news of the institute’s, lets say, problems with the ruling NSDAP having obviously not reached Habana7. Yet while Gropius himself couldn’t be of assistance to Porset he suggested she contact ex-Bauhaus Meister Josef Albers who at that time was employed at the Black Mountain College, North Carolina, one of several unofficial Bauhaus successor institute’s to arise in the United States, and one of the more influential art colleges in mid-20th century America. A suggestion Porset followed, and which led to her spending the summer of 1934 at Black Mountain College, and also to Josef Albers visiting Habana later that year to present a number of lectures. And the start of a long friendship with both Josef and Anni Albers.

In 1935 her participation in protests against the, then, Cuban President Carlos Mendieta, Cuba had an extraordinary number of Presidents in the 1930s, saw Porset, once again, flee Habana, this time to Mexico, and where she was to remain, make her home and develop her career and design understandings.

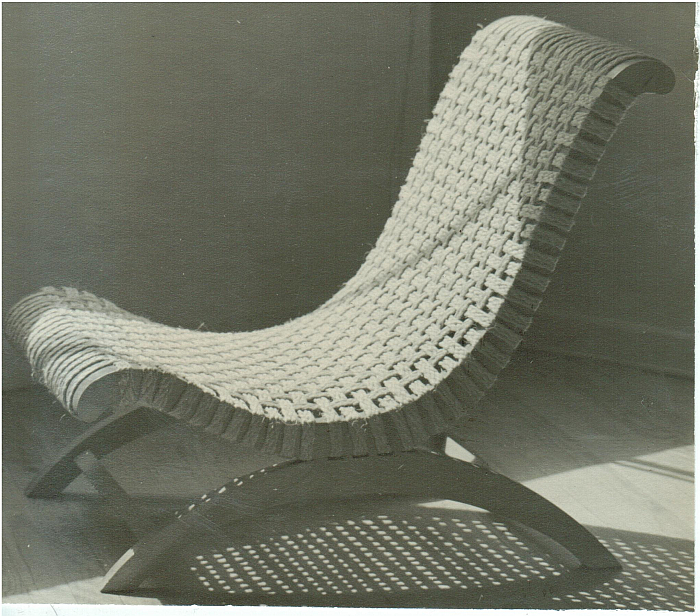

A Butaque by Clara Porset, arguably her most famous project (photo commons.wikimedia.org CC BY-SA 4.0, courtesy Archivo Clara Porset Dumas)

Clara Porset’s first years in Mexico were however spent more in political activism than in designing; initially activism in context of Cuba and the Cuban diáspora in Mexico, but increasingly in context of Mexico itself, a Mexico still seeking its way forward – politically, economically, culturally – from the Revolution; and post-Revolution Mexican activism which saw Porset join the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists, LEAR, an association whose political inclinations can be readily gleaned from their name. And associations with LEAR which introduced her to the muralist Xavier Guerrero, whom she would marry and who would become her most important partner, professionally and privately.

Largely through Guerrero, but also through her own activism, Porset quickly found herself, as Sandra Vivanco phrases it, “integrated into an avant-garde movement comprised of the most important Latin American intellectuals and artists of the time”8, including, and amongst many others, Frida Kahlo, Juan O’Gorman or David Alfaro Siqueiros. And a cultural avant-garde who were actively and ardently exploring and utilising motifs, materials, forms and processes associated with traditional Mexican arts and crafts in context of attempts to establish a post-Revolution Mexican identity, an identity they very much understood in the continuation of an indigenous, vernacular, tradition.

And a movement of which Guerrero was a leading protagonist; thus it comes as no surprise that during her early years in Mexico Clara Porset travelled regularly and widely throughout the land researching traditional, vernacular, approaches, methodologies, materials, forms, etc. Trips and experiences which would inform her understandings of furniture and interior design every bit as much as her exposure to early 20th century European Modernist thinking.

And which in doing so led her away from the harsher expressions of a reduced, rational Modern aesthetic and into the more humane expressions as also advanced by the likes of Alvar and Aino Aalto; into expressions which were an evolution of existing archetypes and process rather than a revolutionary break, and expressions which, if one so will, had a distinct, and very deliberate, very pronounced, Mexican dialect.

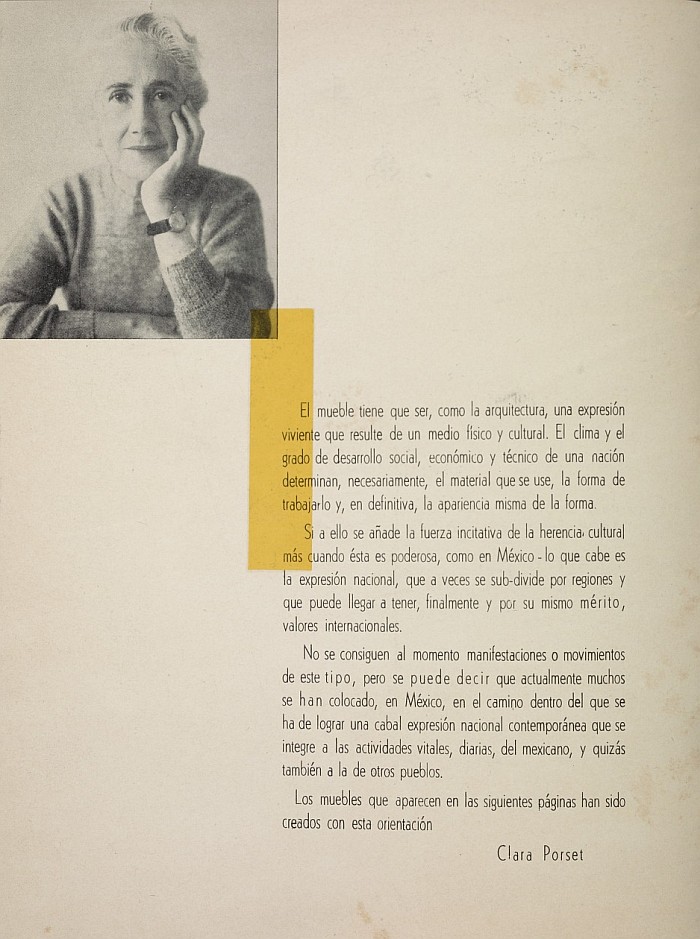

Or put another way, in a 1951 article for the US magazine Arts & Architecture, Porset noted that “my furniture is said to have a Mexican character. If so, it is a natural result of the objectives I seek; for I design chiefly for Mexicans and strive to produce shapes, as adequate as I may, for their specific conditions of living and their active needs which are also specific”.9 A statement which needs to be read in context of her comment in Social in June 1931 that “the unity of current interior decoration is remarkable. This cohesion is produced by the fact that all the elements used in it participate in the same spirit. A spirit so powerful that it allows the concept to develop in different countries, in parallel, without the different racial interpretations altering its essence.”10

However, that “spirit”, and as with any similar spirit, has to evolve in order to remain relevant. And that is exactly what Clara Porset did, evolving, developing that spirit in context of “racial”, i.e. native vernacular, local, realities and conditions. And which, no, isn’t to contradict herself, but to stimulate a very logical, very necessary, process; to evolve, to transfer any such spirit from the universal to the specific, to give a spirit that has developed independent of location an expression that is local, that is relevant to local realities. And that not least because, of the aforementioned social aspects: our societies differ, and so must our societies’ responses to realities, but that can occur within the context of a cohesive, unifying, “spirit” without “altering its essence”.

And a evolution of Modernist ideals within the context of Mexican traditions and contemporary realities which would lead Porset to her first major international success.

A success that occurred without her.

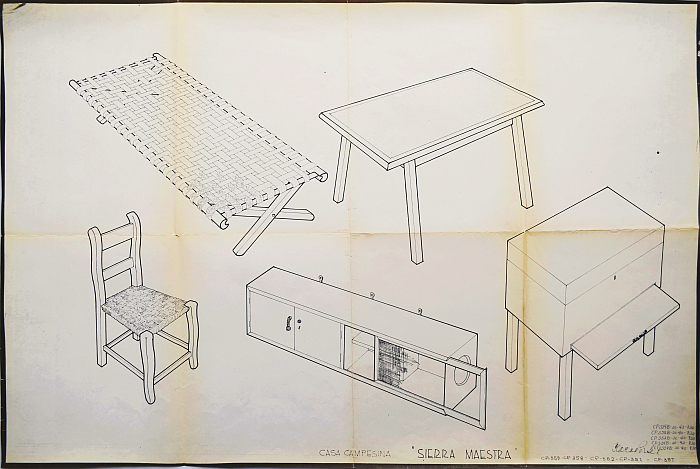

Furniture by Clara Porset & Xavier Guerrero for the 1940 Museum Modern Art, New York competition (photo commons.wikimedia.org CC BY-SA 4.0, courtesy Archivo Clara Porset Dumas)

In 1940 the Museum of Modern Art, MoMA, New York, instigated two furniture competitions, one for US based designers, the Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition which famously saw Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen make their breakthrough with moulded plywood seating, and one for what the MoMA refer to as designers from “the twenty other American republics”11 i.e. South and Central America; a competition initiated with the aim “to discover designers of imagination and ability in the other Americas”, and which announced itself, “interested particularly in bringing out suggestions on the part of these designers as to how their own local materials and methods of construction might be applied in the making of furniture for contemporary American requirements”12, which might not have been as altruistically meant as could be interpreted. Amongst the five prize winners from “the twenty other American republics” one finds Xavier Guerrero. Alone. Without his wife Clara Porset.13

That Guerrero’s winning collection of very simple seating, tables & storage, constructed from pine with ixtle and jute webbing, was also by Clara Porset14 tending to be confirmed by her signature: which is clearly visible on the sketches.

And also by her signature: that use of Mexican “local materials and methods of construction” which MoMA were looking for and which was so integral to, so signatory of, Porset’s approach to and understanding of design. And also, and as Adrian Martinez Moncada opines, the manner in which the collection “does not resonate in the traditional forms of the modern international style, because its formal configuration explores national values that seek to demonstrate the proximity of its design with the rural reality, la labor de cultivo and the pre-Hispanic heritage”15, and to which we’d add, that through its replacement of value as expressed by material, ornamentation and/or ostentation, with value expressed by practicality, functionality and/or versatility, through an honesty of materials, construction and expression, can be considered as very much resonating in the understandings and position of “the modern international style”; as a re-imagining of the native in context of the universal. And thus very much bearing the signature of Clara Porset.

Its relationship to 1920s Europe also being evident in what Martinez Moncada refers to as “its ease of manufacture, it could be realised industrially or in a small carpentry workshop”16

And which leads into a component of Modernist approaches Clara Porset would increasingly bring to her design understandings: industrial production.

Table and lounge chairs by Clara Porset for the Pierre Marqués Hotel, Acapulco (photo commons.wikimedia.org CC BY-SA 4.0, courtesy Archivo Clara Porset Dumas)

“Designs can be produced manually or mechanically, in proportions that vary in different countries according to the degree of development of their industrialisation”17 asserted Porset in 1953.

And Mexico 1953 was still a developing industrial nation, thus as Porset notes “the vast majority of furniture is produced manually”18, specifically, “today artisan production accounts for 70% and industrial production the remaining 30%”.19

And while Porset argues that artisanal production, generally, produces goods of a higher quality, that was also because of, primarily on account of, a lack of effort, lack of care, lack of interest, on the part of industrial manufacturers, and what she refers to as a “passive resignation to the ugly industrial, that implies ignorance of the possibilities of expression through industrial production. The ugliness is felt even more in contrast to the beauties that are produced by hand”20, and a disparity between artisan goods as used by the few and industrial goods as used by the many which leads to the “absurd situation that a people that has extraordinary sensitivity and an indomitable plastic heritage surrounds itself with everyday objects the majority of which do not reflect what [industrial] potentialities could realise”21; thus, although for Porset, the goods of artisanal production should be conserved, maintained and supported, “the industrial design of objects seen and used by everybody everyday, has to be welcomed, guided and promoted” and that not to “would stall economic and cultural evolution, because industrial art is one of the highest and most progressive manifestations of contemporary economy and culture”.22

And thus arguments, debates, on machine production versus manual production, on the beauty derived from objective machines juxtaposed with the beauty derived from subjective humans, on the role of machines in future society, very similar to those undertaken and advanced in inter-War Europe. Just 25-ish years later. And in being such help underscore a certain universality in the relationships between societies and their objects of daily use, in understandings of beauty in context of our objects of daily use; that while such relationships and understandings invariably have geographic and cultural components, they are universally based on an understanding of our objects of daily use as cultural artefacts, as components of the society we are and that which we wish to be. Tacit as that understanding may regularly be.

And arguments that although Clara Porset unquestionably found followers for, Mexican industry wasn’t one of them. Or least not in large numbers. And not in the 1940s and 1950s.

She did however get a chance to demonstrate what she meant by attractive, meaningful, industrially produced furniture.

A dining combination by Clara Porset, undated. The low-back dining/kitchen chair is/was a recurring concept….(Photo courtesy Esther McCoy papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

In 1947 the architect Mario Pani was commissioned to develop the so-called Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán housing estate in the Coyoacán district of southern Mexico City; a project Pani realised as a conurbation of multi-storey apartment blocks featuring not just accommodation but “gardens, a swimming pool, a créche, primary schools, a central laundry and commercial outlets”23; a project very much in line with the ideas inherent in Le Corbusier’s, unrealised, 1930 Ville Radieuse; a social housing project intended to provide “humane housing for one thousand and eighty families of State employees who earn only limited salaries”24; and, according to, Valerie Fraser “the first urban complex of its type in Latin America”.25 And a novel social housing project for which Pani commissioned Porset to develop furniture; furniture which she sought to design so that “they could be built with a very low cost, and seek to make them as resistant, comfortable and pleasing to the eye, as is compatible with the need and intention of achieving a reduced manufacturing cost” and also to “give them the greatest possible lightness to allow them to be used flexibly”26 and of scales and proportions relevant to the interiors of the apartments in which they were to be used, furniture being for Porset not an “arbitrary object” but rather “an architectural element, with fundamental interactions, which force it to be considered in unison with the building.”27

And furniture objects which although formally somewhat removed from those presented at the MoMA New York in 1940 Martinez Moncada argues can be traced back to the 1940 MoMA collection, argues share a common heritage and lineage with the 1940 collection.28 His suspicion being aroused by a note in the MoMA records that the 1940 collection was designed for a project in Coyoacán; and while there may have been a currently unknown project in 1940 for Coyoacán, as Martinez Moncada opines it could also be (almost certainly is) a later, post Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán, addition to the records. And although formally somewhat removed, there are unquestionably material and construction similarities, and also conceptual parallels, that can be drawn and which tend to support Martinez Moncada.29

And furniture which hardly any of the new families purchased: Porset reporting in October 1950, so circa a year after completion, that only 108 of the apartments had been furnished with her designs30, which is exactly 10%, which is a weirdly round number, the rest of the new residents “preferred to bring – out of an unquestioned habit – as many bad and old things as they had or, in other cases, a new and bad collection in which they believed ostentation hid the deficiencies”, and that “in both cases, with the most devastating disparity of scale and character. In this way, Mexico lost its first opportunity to fully face the problem of low cost living”31.

The blame for which Porset primarily placed with the authorities who she felt did too little to actively support the ideals and principles inherent in projects such as Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán; and also industry, those manufacturers of objects in which, so one was led to believe, “ostentation hid the deficiencies” and which meant that “industrial design for the large groups of workers and poor professionals is often of inferior quality, and who accept it without discrimination because they have become prostituted through the mediocre advertising of the press and radio and commercial cinema”32. And which, yes, does sound like Enzo Mari. One of a great, great many statements by Clara Porset that could just as easily have come from Enzo Mari. We don’t know if they ever met. We really hope they did.

Yet despite her fervent belief in the necessity and urgency of developing high-quality industrially produced furniture, readily affordable for all Mexicans, in the course of the 1950s, Clara Porset’s work developed in a different direction.

Clara Porset and Alfonso Rojas moulding plywood chair backs (Photo courtesy Esther McCoy papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Through her connections with, firmly established place amongst, the cultural avant-garde elite of mid-20th century Mexico, Clara Porset regularly cooperated with many of the leading Modernist inclined Mexican architects of the period, creating furniture and interior designs for projects by the likes of the aforementioned Mario Pani, or Enrique Yáñez for whom she contributed to the interior of the Centro Médico Nacional, or Luis Barragán, including, and most symbolically, creating furniture for the houses, villas, Barragán, and the likes of Max Cetto, designed for the so-called Jardines del Pedregal, an upmarket estate developed on the southern edge of Mexico City. A project which although physically close to the Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán is conceptually in another world.

Similarly the high-end, hand produced, furniture Porset developed for the high-end residents of Jardines del Pedregal exist in a world conceptually far, far, removed from the low-cost, industrial furniture Porset developed for the lower-end residents of Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán.

A dichotomy which, again, reminds very much of that which existed in inter-War Europe as socially motivated architects and designers, largely, earned their living through projects for their bourgeois contacts, and that, largely, because of the lack of popular acceptance and/or support for either their socially motivated projects or for the formal, material and constructional realities of the works their understandings of and positions to architecture and design led to. Works which are widely celebrated and copied today.

And a dichotomy which although profitable for Porset, as Randal Sheppard notes, she became increasingly disenchanted by: in 1955 Porset travelled to Helsinki to participate in the so-called World Assembly for Peace, an initiative of the, then, Soviet sponsored World Peace Council, stopping en route in Sweden to visit the H55 exhibition in Helsingborg, one of the more influential architecture and design exhibitions in 1950s Scandinavia, that exhibition which neatly elucidated how understandings of architecture and design in Scandinavia had evolved and developed since Stockholm 1930, and also, intrestingly, visiting Finn Juhl in Copenhagen, experiences which caused her to lament in a letter to Guerrero that, “seeing all this, I realize – without false modesty – how very far in our furniture we have been above all the others who make furniture in Mexico, or at least they say they make it. And I say ‘have been’ in past tense because I also think I have left behind the simplicity and purity of the early times due to the need to make furniture splendorous so that the bourgeois [client] will accept it.”33

A conceptual drift away from the honesty of the 1940 MoMA collection, from the low-cost furniture of Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán, from utility of industrial production, Clara Porset understood as “a genuinely damaging concession”.34

However, by the late 1950s a new opportunity was developing across the Gulf of Mexico in her native Cuba.

Clara Porset’s introduction to the catalogue for IRGSA’s collection of her designs released under the title Prestigio en Muebles de Madera, and for which she became the first furniture designer in Mexico to receive royalties on sales, catalogue ca 1951 (Courtesy Esther McCoy papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

As well as joining the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists in the 1930s Clara Porset also joined the Communist Party, remaining, as best we can ascertain, a committed Communist, and, arguably, and despite her very wealthy middle class backgound, the dichotomy between the very wealthy bourgeois clients she increasingly acquired in the course of the 1950s and the politics she followed also played a part in the dispondancy she expressed to Guerrero.

And, arguably, also played a part in her decision to return to Cuba following the 1959 Revolution in order to contribute to the establishment of the new republic. A contribution which, and in addition to many other projects, saw Fidel Castro personally commission Porset35 with the development of furniture for the Ciudad escolar Camilo Cienfuegos, an educational campus sited near Bartolomé Masó in the Sierra Maestra as a school for peasant children who otherwise would have had only limited access to a formal education, and for which Porset developed not only furniture for the classrooms but also the accomodation blocks.

In addition Porset was entrusted with the development of a Cuban design school; a project which saw Porset visit numerous design schools in Europe by way researching contemporary design education, Óscar Salinas, noting, amongst many other locations, Halle, Weimar and Berlin36, one presumes Ost; which interestingly means that while Porset didn’t visit Bauhaus she did visit institutions staffed by innumerable ex-Bauhäusler and who, and at least after the cessation of the Formalism Debate of the early 1950s, took that advanced by Bauhaus and their ilk and evolved and developed it in context of the new realities. Thus a development of inter-War positions and ideals, that inter-War spirit, akin to that which Porset had advanced. Just in a different context. And although Porset formally took up the post of Director of the still unopened Cuban Design School, the inevitable underhand jockeying for position, influence and power on which any political regime is based saw her quickly replaced by those with better contacts.

And saw Clara Porset return to Mexico in 1963.

Where, according to Salinas, “she was surprised to find that many architects had turned their backs on her because of her involvement with Communist organizations and her collaboration with the Cuban Revolution”.37 A “surprise” we can understand, for Porset’s political persuasions must have been known; Porset and Guerrero had been leaning heavily left for decades, it couldn’t have been a secret, and so, arguably, it was the, personal, association with Castro, Guevara et al, that was the bigger issue in 1960s Mexico City. A state of affairs which reminds very much of the Dutch architecture community’s distancing of themselves from Mart Stam following his sojourns in first the Soviet Union and subsequently East Germany.

And a state of affairs which saw Porset concentrate on education; Porset developing numerous, unsuccessful, plans for a Mexican school of industrial design, before the opening in 1969 of an Industrial Design department at the National School of Architecture saw her appointed as a Professor of Industrial Design. A tenure Clara Porset held until her death in Mexico City on May 17th 1981, a week short of her 86th birthday.

A beach/garden chair by Clara Porset for the Pierre Marqués Hotel, Acapulco …. and the purest of joys (photo commons.wikimedia.org CC BY-SA 4.0, courtesy Archivo Clara Porset Dumas)

Although Clara Porset is arguably best known for her Butaque, her adaptation of a traditional Spanish chair brought by colonialists to the contemporary Mexico and subsequently adopted by the wider population; and joyous a work as the Butaque, or perhaps more accurately given the number of variations she developed, joyous a project as the Butaque unquestionably is, it cannot on its own adequately encapsulate Clara Porset.

And while regrettably, if unavoidably, limitations of time and space prevent us from discussing Clara Porset’s extensive furniture oeuvre in any depth or detail, mention must, must, be made of works such as Guerrero and Porset’s entry for the MoMA New York’s 1949 International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design38, a metal wire chair which, we’ll be honest, we’re not entirely sure can work, but if it can, which it possibly could, may just be the most resilient chair you’ve never sat on; the so-called Totonaca chair, a work inspired by a 5th/6th century CE sculpture originating amongst the Totonac of southern/central Mexico and which exists as a 20th century Totonac sculpture, and thereby expresses ist easy, organic, unassuming sculpturality freed from all historical binds; the myriad furniture Porset developed for the Pierre Marqués Hotel, Acapulco, a commission which saw her become the first furniture designer in Mexico to receive royalties from the sale of their designs39, and thus Mexico’s first professional furniture designer in the sense the term is understood today, a collection which won a Silver Medal at the 1957 Milan Triennale, and a collection which includes a low-down woven wicker beach/garden chair which we’ve never met in person, but we’re claiming is the purest of joys, formally, materially, conceptually.

Amongst many, many, other delightful moments in a varied and engaging canon of works.

A canon of works which allows for differentiated reflections on not only the aforementioned humane Modernism of the Aaltos, but also, for example, the understandings and approaches of a William Morris and the Arts and Craft movement of the late 19th century, of Kaare Klint’s reworking of exisiting designs in the inter-War years rather than developing the new, of Charlotte Perriand’s work in 1940s Japan where she applied Modernist ideas in context of traditional Japanese craft, most famously re-working the 1920s steel tube Chaise Longue developed with Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanerret in bamboo, of the Formalism Debate as staged in early 1950s East Germany, of the Neoliberty of 1950s Italy, that early forbearer of Italian Postmodernism, of the flowing curves of a Luigi Colani as an attempt to bring the organic to the rational, amongst the many other re-interpretations, re-positionings and responses to industrialisation and Functionalist Modernism that one finds scattered along the helix of furniture design.

And a canon of work which poses the question, why is Clara Porset so (relatively) anonymous on that helix?

A question partly answered by the fact her works were, largely, only produced, sold and thus known, in Mexico and Cuba. And not further north in the United States.

In the 1940s Clara Porset made several trips to the United States looking for cooperations, and successfully persuaded Artek-Pascoe, that vehicle via which at that time Artek furniture was imported to America, to present a showcase of her furniture in their New York flagship store in 194740; and in the early 1950s the influential American architecture historian and journalist Esther McCoy attempted to introduce Porset’s designs in America, more specifically southern California, the above quoted Arts & Architecture feature being part of that attempt. And McCoy appears to have had a certain, if limited, success.

But then, arguably, politics intervened: the 1950s seeing the increasing development and intensification of the Cold War, including in the early 1950s the re-emergence of Stalin’s Formalism Debate, as, and generalising more than is advisable, an attempt to declare Soviet culture as more authentic and responsive to the needs of society than American culture. And thus whereas 1940s America had been an opportunity, 1950s America was, arguably, for a committed Communist such as Clara Porset, imperialist, in contrast to the thoroughly unimperialistic Soviet Union, obviously, and so, arguably, 1950s America wasn’t an option for her, arguably, wasn’t a society she wanted to associate with. And, yes, we did use “arguably” a lot, because as far as we can ascertain the question of why Clara Porset concentrated in the 1950s on Mexico rather than seeking commercial cooperations in the USA isn’t one that has been fully, focusedly, approached.41 Yet needs to be.42

For what if rather than spending time in the Jardines del Pedregal, Clara Porset had travelled to Berne, Indiana, to Zealand, Michigan, to East Greenville, Pennsylvania, to Chicago, Illinois, to New York, New York? American furniture design as an industry, as a proactive response to prevailing conditions, as a furniture design industry that could accommodate Clara Porset, essentially, and generalising dangerously, begins in the late 1940s, picking up speed throughout the 1950s before slowing in the 1960s. In addition Mexico and Mexican folk art were important sources of inspiration and guidance in context of mid-20th century US design, Charles Eames and Alexander Girard being but two examples, if two very good examples. And one can’t help thinking that Clara Porset with her approach to and understandings of furniture and furniture design could have, for example, ably complimented a Edward J Wormely at Dunbar, or contributed to Knoll office programmes, found homes in hotels and restaurants across the United States, in addition to providing Americans with low-cost, industrially produced domestic furniture.

But Clara Porset didn’t visit 1950s America, she spent time in the Jardines del Pedregal and then travelled to post-Revolution Cuba. But what if……..?

For one thing we’d have a lot more Clara Porset furniture than we have today.

That limited furniture which we do have, we’d argue, and that without having physically seen much of it, knowing much of Porset’s oeuvre alone through photos, which is never ideal, never allows you to fully engage and converse with it, but which despite that, we’d argue, is (primarily) furniture that on account of the honesty inherent within its genesis as responses to questions approached with a considered, critical and responsive understanding of what furniture is and the relationships of furniture to the user, space and society, that as works which are not about the object but what they represent and embody, are objects that remain as valid today as when they were first developed. And are works that while they may have been developed for Mexicans, were and are applicable for all, everywhere. A lot of Clara Porset’s works are crying out for re-issues.

Not that Clara Porset is and was just furniture objects. She isn’t and wasn’t. Clara Porset is and was also her many, many texts where she discusses not only design and designers but explains and elucidates her understandings of furniture design and its relationships to architecture, individuals and society. Clara Porset is and was also her teaching, starting from her tenure at the Rosalía Abreu Foundation Technical School for Women in 1930s Cuba, moving over various stations in Mexico to the Industrial Design department at the National School of Architecture and continuing posthumously via the Premio de Diseño Clara Porset, established by Clara Porset in her will by way of using her estate as the basis for a scholarship to allow female Mexican design graduates to undertake postgraduate studies, but which on account of devaluation of the Peso exists today as biannual design competition for female Mexican design students.43 Clara Porset is and was also her exhibition design, perhaps most famously the 1952 showase El Arte en la Vida Diaria where in the juxtaposition of indigenous craft goods and industrial goods Porset sought to underscore her position on the unity of Mexican tradition and industrial design, and, one of the many, many important, interesting and informative moments in Clara Porset’s biography we have skipped over. By necessity, so rich and varied is that biography.

And a biography which allows one to understand that the answer to the question ¿quién es Clara Porset? is a complex one, but one whose inherent complexity means that approaching an answer to ¿quién es Clara Porset? can help us all approach not only a better understanding of the (hi)story of architecture in Mexico, of the development of industrial design in Mexico, of the development of furniture design in Mexico and by extrapolation on account of the many international interfaces, the development of architecture, industrial design and furniture design globally; but for all approaching an answer to ¿quién es Clara Porset? allows us all to approach more durable, responsive and sustainable answers to the question “¿qué es diseño?

Happy Birthday Clara Porset!!

Clara Porset. Diseño de interiores y muebles (Courtesy Esther McCoy papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

1. Clara Porset, ¿Qué es diseño?, Arquitectura México, 28, Julio 1949, Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021) And a huge Thank You to the Facultad de Arquitectura at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for making so many Mexican architecture and design magazines freely available online. A huge aid to allowing for better understandings of the (hi)story of architecture in Mexico, and beyond…..

2. See, for example, Antonio Stefanelli, The Art of Daily Life Objects. Charlotte Perriand and Clara Porset. Dialogue with Tradition, PAD. Pages on Arts and Design, Nr. 18, June 2020

3. Jorge R. Bermúdez, Volver a Clara Porset Oficina Nacional de Diseño Online http://www.ondi.cu/__trashed-19/ (accessed 25.05.2021)

4. There seems to be some confusion as to when Clara Porset returned to Cuba. Randal Sheppard (see note 33) dating it as “late 1929”, Museo Franz Meyer (see note 35) date it as 1932, and while we’re not entirely sure why there is confusion, part of it may be that in 1930 and 1931 she can be placed more or less simultaneously in both Cuba and Europe, which may imply that she regularly travelled between the two.

5. Important also to consider that the Art Déco for which Habana is so popularly associated developed in Cuba, and generalising dangerously, in the 1930s, and thus at that time Clara Porset was advocating an alternative path forward for the furniture and interiors of Cuba. And to consider that for all the Art Déco in Habana there is also some Modernist architecture. No artistic or creative moment ever existed alone, any age is always a mix of positions and ideas.

6. Clara Porset, Resumen de las exposiciones de arte decorativo moderno en 1930, Social, Febrero 1931 Available via https://archive.org/details/cubanmagazinesnewspapers (accessed 25.05.2021)

7. Although Clara Porset travelled extensively in Europe in the late 1920s/early 1930s, we can find no evidence that she visited Germany. If that was simply a question of lack of time, lack of opportunity, or because Germany wasn’t that high on her list of priorities is unclear. However had her interest in Modernist tendencies been fully awoken in the late 1920s, so when she was definitely in Paris, one presumes she would have found time and opportunity to visit Bauhaus Dessau, Burg Giebischstein Halle, Weissenhofsiedlung Stuttgart, Neues Frankfurt, et al….. And in context of the later she may have met Max Cetto, with whom she closely cooperated in Mexico following his immigration.

8. Sandra I. Vivanco, From Resort to Gallery: Nation Building in Clara Porset’s Interior Spaces, Dearq, 23. Mujeres en Arquitectura V. 2, January 2018

9. Clara Porset Guerrero, Chairs by Clara Porset, Arts & Architecture, July 1951

10. Clara Porset, El concepto actual de la decoración moderna, Social, Junio 1931 Available via https://archive.org/details/cubanmagazinesnewspapers (accessed 25.05.2021)

11. The Museum of Modern Art announces terms of two design competitions for home furnishings, Press Release, September 30th 1940, Available via https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/630/releases/MOMA_1940_0061_1940-09-16_40916-54.pdf

13. In the interests of fairness (a) we don’t know if the entry was submitted as Guerrero & Porset or just as Guerrero, Adrian Martinez Moncada (see note 15), for example, argues that Guerrero & Porset may have been confused about the rules, may have been uncertain as to whether joint/team projects could be submitted or only individuals could apply and thus entered it as Guerrero alone, which is theoretically possible, (b) Randal Sheppard (see note 33) states that it was in fact Guerrero alone, the reference he quotes to back up his claim being in the sort of archive we currently cannot access, but which we will just as soon as the situation allows (c) the MoMA did retrospectively credit Porset and it is now listed as a joint entry. However, despite at attempts at fairness, as previously noted the MoMA does have long tradition of ignoring female designers: Lilly Reich was not only ignored in the 1947/48 Mies van der Rohe exhibition but the catalogue notes that Reich “soon became his equal in” exhibition desgn, which is an absurd claim to make, and Mies knew that; Alvar Aalto alone being honoured in 1938 and that despite every other exhbition until that point being Aino and Alvar Aalto, in that order, while the catalogue notes “1925 Marriage with architect Aino Marsio; all works after this date are in collaboration with Mrs. Aalto”, but the exhibition was Alvar alone; while into the 1970s the MoMA remained silent on Ray Eames’ contribution to the Eames’ canon. As we’ve noted before, anyone wanting to understand why so many early and mid-20th century female designers have slipped into, at least partial, invisibiilty could do worse than starting their research in the MoMA archive. And then asking why the likes of Mies van der Rohe, Alvar Aalto and Charles Eames consented to the MoMA’s understandings, rather than refusing to cooperate.

14. As ever when consider design by individuals who were professional and private couples there is always the question of how much the various parties contributed both directly and indirectly to any given project, and Xavier Guerrero was without question important in the development of Clara Porset’s positions and understandings of design, but not exclusively, that process had begun before they met and she continued very much in her own way. And certainly a more concentrated, focussed, exploration of the work of Porset and Guerrero in context of the other would be very welcome. Apologies if it exists and we’ve missed it.

15. Adrián Martínez Moncada, Genealogía del conjunto campesino de Xavier Guerrero y Clara Porset, MA Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Junio 2019 Available via http://132.248.9.195/ptd2019/junio/0790440/Index.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

17. Clara Porset, Diseño viviente, Espacios 15, Mayo 1953 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

19. Clara Porset, Diseño viviente. Hacia una expresión propia en el mueble, Espacios 16 Julio 1953 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

20. Clara Porset, Arte en la industria, Arquitectura México, 29 Octubre 1949 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

21. Clara Porset, El arte en la vida diaria, Espacios 10, Agosto 1952 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

22. Clara Porset, Arte en la industria, Arquitectura México, 29 Octubre 1949 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

23. Valerie Fraser, Building the new world: studies in the modern architecture of Latin America, 1930-19, Verso, 2000

24. Clara Porset, El Centro Urbano “Presidente Alemán” y el espacio interior para vivir, Arquitectura México 32 Octubre 1950 Also includes photos of Porset’s furniture designs. Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

25. Valerie Fraser, Building the new world: studies in the modern architecture of Latin America, 1930-19, Verso, 2000

26. Clara Porset, El Centro Urbano “Presidente Alemán” y el espacio interior para vivir, Arquitectura 32 Octubre 1950 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

27. Clara Porset, El mueble en la arquitectura, Espacios, 1, Septembre 1948

28. Adrián Martínez Moncada, Genealogía del conjunto campesino de Xavier Guerrero y Clara Porset, MA Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Junio 2019 Available via http://132.248.9.195/ptd2019/junio/0790440/Index.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

29. Not uninterestingly the sketches of the 1940 collection as stored in the Clara Porset archive feature the words “Sierra Maestra”, that region of Cuba where the Ciudad escolar Camilo Cienfuegos was built. Was that added before or after the Cuban commission? Martínez Moncada very neatly follows the path of the 1940 collection from MoMA to the Ciudad escolar Camilo Cienfuegos and so it could well be an even later addtion….

30. Clara Porset, El Centro Urbano “Presidente Alemán” y el espacio interior para vivir, Arquitectura 32 Octubre 1950 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

31. Clara Porset, Diseño viviente. Hacia una expresión propia en el mueble, Espacios 16 Julio 1953 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

32. Clara Porset, El arte en la vida diaria, Espacios 10, Agosto 1952 Available via https://arquitectura.unam.mx/raices-digital.html (accessed 25.05.2021)

33. Letter from Clara Porset to Xavier Guerrero, June 19th 1955, Archivo Clara Porset, quoted in Randal Sheppard, Clara Porset in mid twentieth-century Mexico: The politics of designing, producing, and consuming revolutionary nationalist modernity, The Americas, Volume 75, Number 2, April 2018

35. Óscar Salinas, A Life’s Work, in Museo Franz Mayer, Clara Porset’s Design. Creating a Modern Mexico, Museo Franz Mayer, 2006

38. Interestingly, whereas in the International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design exhibition catalogue Porset & Guerrero are given co-authorship of their chair, the Eames Office entry, the future plastic chair shells, is Charles alone…. catalogue available via https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1795 (accessed 25.05.2021)

39. Óscar Salinas, A Life’s Work, in Museo Franz Mayer, Clara Porset’s Design. Creating a Modern Mexico, Museo Franz Mayer, 2006. The contract was with IRGSA and according to Salinas also included two office furniture collections, one in wood, one in metal. We are trying to track down examples…….

40. See, for example, Mary Roche, Furniture depicts different Mexico, New York Tims, February 4th 1947

41. Randal Sheppard briefly introduces various aspects of such questions, and offers indications as to where answers may be found, see Randal Sheppard, Clara Porset in mid twentieth-century Mexico: The politics of designing, producing, and consuming revolutionary nationalist modernity, The Americas, Volume 75, Number 2, April 2018

42. As does the question if any European manufacturers approached her after the 1957 Milan Triennale, and if not why not? Porset’s works, argubaly, certainly fitting in very well with many of the late 1950s Italian manufacturers portfolios…..

43. Óscar Salinas, A Life’s Work, in Museo Franz Mayer, Clara Porset’s Design. Creating a Modern Mexico, Museo Franz Mayer, 2006

Tagged with: Clara Porset, Cuba, Design Calendar, Habana, Mexico, Mexico City