The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture at the Architekturmuseum der TU München

Amongst the great many delights of the exchange, the interplay, between German and English is the word ‘Gift’:

| German | English |

| Gift | Poison |

| Geschenk | Gift |

An interplay that, apart from all the other joys it brings, allows one to rephrase Virgil’s “timeō Danaōs et dōna ferentēs” ‘Beware Greeks bearing gifts’ as ‘Beware Germans bearing Gift‘.🤣

With the exhibition The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture the Architekturmuseum der TU München explore architecture as a Geschenk and architecture as a poison…….

In many regards the architectural bequest is as old as architecture itself, one thinks, for example, in context of religious houses of all denominations, those earliest examples of construction as a conscious, consciously, artistic, functional, representative practice. Those earliest examples of construction as architecture. And of architecture as a bequest.

The discussion undertaken by The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture is also primarily historic but much more recent historic, post-1945 historic. A discussion undertaken in context of four locations and four themes: Skopje, Kumasi, Ulaanbaatar and East Palo Alto and The Humanitarian Gift, The Land Gift, The Diplomatic Gift and The Philanthropic Gift, respectively. Locations and themes approached and explored in a framework of four concepts: Generosity and Violence, with its reflections on the power relationships betwixt bequester and bequestee, the exercise of power inherent in an architectural bequest; Social Bond, bonds not necessarily about friendship but influence, primarily of bequester over bequestee, but in which the latter can have an active role; Producing a Gift, the process(es) of transforming an offer into something tangible; and Afterlives, that all important ‘what happened next’, ‘what happens next’, the durability of a project.

A narrative, an exhibtion, there is no one nor one optimal route through. But which given the spatial realities of the Architekturmuseum der TU München, the fact it’s a linear space, you need to pass through twice: once on the way there and then once on the way back. OK not necessarily, since we were last in the Pinakothek der Moderne they have opened a door between the art space and the architecture space which means you can enter and/or depart The Gift in the middle, as the great many school groups drifting through the museum did. But don’t. Stay in the Architekturmuseum der TU München and explore The Gift in two directions, as a return journey in the company of the many thoughts and considerations and questions stimulated during that journey. And in context of the double meaning of ‘Gift’.

A journey through Kumasi, Ghana, to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

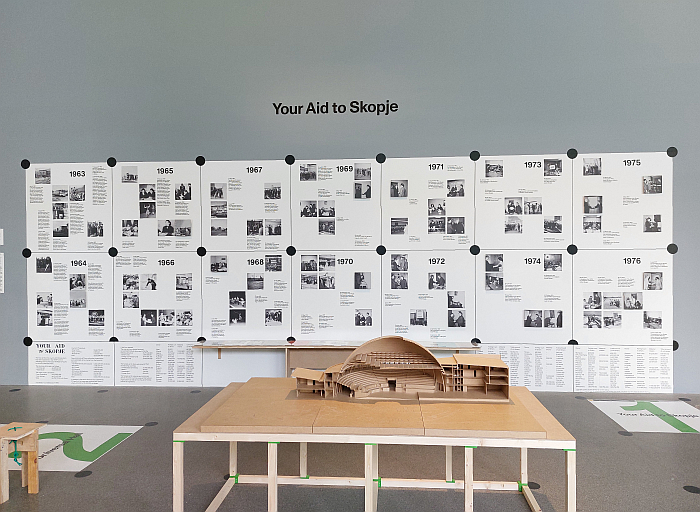

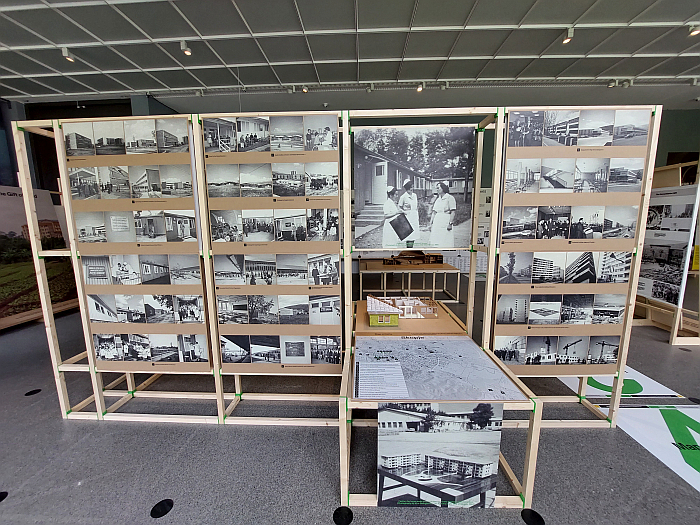

A journey that The Gift begins both as an exhibition and, in many regards, as a curatorial concept, in Skopje, then Yugoslavia, now North Macedonia, in 1963 and the myriad rebuilding projects initiated, necessary, following the earthquake of July 26th; rebuilding projects, a Humanitarian Gift, contributed to by over 80 nations; rebuilding projects that at the height of the Cold War brought East and West together while increasing the visibility of the neutral Non-Aligned Movement, of which Yugoslavia was a rare European member. And building projects from which The Gift focuses in particular on the United Nations initiated architectural programme to rebuild the city, a programme most popularly associated with Kenzō Tange’s plan for downtown Skopje, Japanese Metabolism in the heart of the Balkan Peninsula, if a plan only partially, incompletely, realised, thus making it a useful example of the, as a Lucius Burckhardt continually reminds us all, myriad problems of large scale, comprehensive, urban redevelopment programmes. And also the problems, and folly, of ‘Utopias’. ¿Utopias as generosity and violence? And also focuses on the new housing estates, the earthquake had left some 150,000 individuals, around 75% of the, then, population of Skopje, homeless, and new estates that weren’t just about new houses, but novel infrastructure, novel positions on housing and urban design, and also a wide experimental field for the developers of prefabricated, industrial, construction systems. Those systems we still so badly need. And also a focus on the so-called Universal Hall, a multi-use auditorium constructed from a prefabricated system developed by Sofia, Bulgaria, based Technoeksportstroy and financed by some 35 nations. And a Universal Hall, in many regards the symbol of the international, trans-alliance, trans-ideological, assistance for Skopje, that in its current state of disrepair, and its place in the political discussions of contemporary North Macedonia, is both an excellent metaphor for our contemporary global geopolitics, contemporary developments in geopolitics, and also a good reminder of the complicated demands of caring for cultural buildings over the undulations of fate and time, of caring for buildings housing culture, buildings considered components of a culture, buildings that have taken on a cultural significance over and above their physical function and purpose.

Complications of relationships with buildings over the undulations of fate and time also inherent in the discussions from Kumasi, Ghana, in context of the campus of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, KNUST, an institution founded in 1951, in colonial era Gold Coast, as the College of Technology, before being renamed in honour of the post-colonial, anti-imperialist, pan-Africanist President Kwame Nkrumah; and a University built, as one learns, on land owned by the Asante, land which was not only farmed by the Asante but also used for burials, land the Asantehene, the King of the Asante, leased to the British in 1950 for 60 years. Or leased it according to the Asante, according to the British, and the subsequent post-colonial, anti-imperialist, pan-Africanist governments the land was gifted. A small, but very important, difference. Whereby we’d also ask what did the Asantehene think was going to happen after 60 years? Did he plan to demolish the campus? Or did he believe the British would still be there and felt himself coerced to agreeing? But that’s another discussion, the discussion in The Gift is that on the conflicts that invariably arose, and continue to exist, on account of the Land Gift between the local population and the university, a local population who, as one learns, were once regularly given jobs at the university, as was originally agreed when the lease/bequest was made, but who increasingly aren’t, with the associated frustration and irritation and alienation; a local population who occasionally get infrastructural bequests from the university, including schools, but a local population, one gets very much the impression, who feel short changed by the university, feel promises aren’t being kept, and feel actively let down by the university in the case of the quality of the teaching at the new schools, a reminder that a school is much more than a building to which we shall shortly return; a local population who, as the university has grown in size over the decades have experienced housing crises on account of the population rise, crises the university have responded to through the development of novel house construction and design projects based on local skills and materials, and which, one learns are finding adaptations elsewhere in Ghana. But housing crises nonetheless. ¿Education as generosity and violence?

And a local population who need land to farm. Have land to farm. Land on which stands a university. Land on which ever more university stands as it grows and expands. And thus a very neat reminder, a very neat example of, that reality that we only have so much land, but myriad, at times incompatible, if equally valid requirements, for that land: farming and food production is important, education is important, recreation is important, no one is more important than any other. Decisions on land use have to be made.

Who should make those decisions?

How should those decisions be reached?

Discussions on the Universal Hall, Skopje, North Macedonia, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

From Kumasi The Gift continues its eastward journey to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, and specifically to the great many pre-1989 architecture bequests of the Soviet Union and China, in particular the 1970s and 80s housing estates bequested by the Soviet Union in the Mongolian capital; estates, Diplomatic Gifts, that saw the yurts and gers of yore replaced by prefabricated apartment blocks in which the residents not only had fixed walls, running water and electricity, but, direct, neighbourhood, access to new health, education and social infrastructures. Changes then, since and now followed in The Gift via the example of the apartment of family Damdinsuren; an apartment Chimed and Nergui Damdinsuren took possession of in 1981, in which they raised their four children, in which their daughter Ariungerel raised her three children, and which they now share with their granddaughter Temuulen. A relative stability within the apartment of the Damdinsuren’s that stands diametrically juxtaposed to the changes in the neighbourhood over the intervening forty years — a juxtaposition, and digressing slightly, also neatly integrated into the scenography, very neatly — not least those demographic, economic and political changes associated with, necessitated by, the collapse of the Soviet Union and Mongolia’s need to re-find its place in the global political and economic systems. And also the social changes over the decades; The Gift featuring input from four long term residents of so-called Micro-Distict 4 all of whom in lamenting the changes that have occurred at the social, community, level allow access to appreciations of community as solidarity, community as responsibility, community as obligation. And community as control. ¿Community as generosity and violence? And while, and given the context of the past being described, it’s very easy to dismiss, for example, memories of a joint, a communal, cleaning of the estates as laments for a retrotopic ‘Soviet’ of yore, such thoughts should, need, must, be made in conjunction with reflections on the Japanese practice of toban, of school children being responsible for cleaning their schools, or the examples discussed in context of studio b severin’s project Cleaning against the Dictatorship of Efficiency of office workers both being responsible for cleaning their office block and also collecting litter in the vicinity. ¿Is that “Soviet”? ¿Duty? ¿Friendship? ¿Imposition? ¿Social? ¿Political? ¿Cultural?

The Gift ends its narrative, or ends its main narrative, in East Palo Alto, California, a community that, as one learns, was once the murder and drug capital of America and which today exists in the shadow, financial and physical, of the tech conglomerates of Silicon Valley, including Meta to the north and Alphabet to the south, and to the west Stanford University. The eastern flank is guarded by San Francisco Bay. And an East Palo Alto explored from, in effect, two perspectives: that of the residents of so-called Whiskey Gulch a, let’s say, less prosperous area of East Palo Alto which has slowly been redeveloped, has been razed and rebuilt, a process with very direct, tangible, consequences for those (former) residents forced to relocate, forced to give up that community the residents of Micro-District 4 so strongly lament, also so strongly lament; a fate of a community which, standing in The Gift, one can’t help associating with the all-pervasive shadow of the tech conglomerates. ¿Tech conglomerates as generosity and violence? And which also posses important questions, as does The Gift, of racial equality in Silicon Valley, of racial equality in gentrification, of racial equality in the urban (re)development of contemporary America.

And also from the perspective of three cultural and educational projects, three Philanthropic Gifts from wealthy patrons: the EPACenter bequested by the John & Marcia Goldman Foundation, a waterfront redevelopment project planned by Laurene Powell Jobs’ Emerson Collective, and the eponymously titled The Primary School funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, projects that as one can read have enjoyed not only various degrees of success but various degrees of public support. And a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative in context of education, a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative with a say in the curriculum of a school, and the software that is used in that curriculum — whereby, and digressing once again, the word ‘dogfooding’ used in context of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative is now officially our favourite new word, and one that we hope to use at least once a month, many thanks to the curators therefor… a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative in context of education, a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative with a say in the curriculum of a school, and the software that is used in that curriculum, that automatically, involuntarily, leads you to imagine Elon Musk as being responsible for a school curriculum. ¿Tech conglomerates as generosity and violence? And also takes you back to the 2022 Bauhaus Lab Doors of Learning. Microcosms of a Future South Africa as presented at the Bauhaus Building, Dessau, and to the (hi)stories of the schools and colleges established by the African National Congress in Tanzania for exile Black South Africans; schools that, as with the rebuilding of Skopje, were financed and supported by nations on both sides of the Cold War, and unaligned nations, and schools that for all they taught maths and science and languages were heavily politicised, we’re ideology based. And thus for all the greater sympathy and solidarity one may have with anti-Apartheid activists and the victims of Apartheid over tech billionaires, there are clear similarities. Not least the question: who should decide what should be taught in schools and how it should be taught?

Who should decide what should be built, and how it is built?

Who should decide on our built environment?

Who should make decisions on land use?

How should those decisions be reached?

¿Humanitarian aid as generosity and violence?

¿Education as generosity and violence?

¿Culture as generosity and violence?

¿Diplomacy as generosity and violence?

¿Philanthropy as generosity and violence?

¿Tech conglomerates as generosity and violence?

Just some of the thoughts and considerations and questions you can, should, reflect upon as you turn to the west and return from East Palo Alto to Skopje via Ulaanbaatar and Kumasi.

An introduction to educational and cultural initiatives by the John & Marcia Goldman Foundation, Emerson Collective and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative in East Palo Alto, California, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

As an architecture and urban planning exhibition The Gift very naturally brings with it all the challenges and complexities of presenting the architectural and urban planning scale at the museal scale; a complex challenge it, primarily, approaches through the use of texts, photos, videos and plans, and thus an exhibition format that can at first appear daunting. But don’t let it daunt you. Engage with it, accept you’re going spend longer than 20 minutes there, relax, breeeeeeaaaaaathe; and if you do you’ll discover an exhibtion that through the ready accessibility of the monolingual English texts1, texts joyously free of architectural academese, and also through the personal perspective of the narration, a narration that isn’t led by the curators, far less by architects and urban planners, but is led by the residents of Skopje, Kumasi, Ulaanbaatar and East Palo Alto, that not only entices you to travel further, to think further, but leaves you wanting to travel deeper into the myriad subjects and discussions it opens.

Subjects and discussions, and their very satisfying framing in a 4 x 4 x 4 format, architects 🙄, that through the course of your journey helps focus your attention on that fact that for all architecture is popularly considered an artistic, functional and/or representative practice, and popularly associated with architects’ ‘visions’, ultimately architecture is about creating spaces in which human life can unfold, architecture is about people, collective and individual, not about buildings, and that thereby people must be at the heart of what is undertaken. But are they always? ¿When an architect has a ‘vision’? ¿Or a developer smells profit?

And a format which also encourages you travel beyond Skopje, Kumasi, Ulaanbaatar and East Palo Alto, encourages you to think beyond The Humanitarian Gift, The Land Gift, The Diplomatic Gift and The Philanthropic Gift and to consider further examples of Social Bond, Producing a Gift, Afterlives and Generosity and Violence; encourages you to reflect on, for example, Olympic Games and similar large sporting events, or the social housing estates and programmes of 1920s and 30s Europe as so popularly represented by Neues Frankfurt, or the company towns of yore that are, apparently, arising from their slumber, or China’s contemporary interventions in Africa, or the development of the museum areal in Munich’s Maxvorstadt, or the bequests in Germany and America studied in seminars by students at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning in Ann Arbor and the TU München’s Chair of History of Architecture and Cultural Practice, discussions presented at the end of The Gift and which very pleasingly extend the main narrative. Or the varied and various architecture and urban planning programmes of the NSDAP as featured in Power Space Violence. Planning and Building under National Socialism at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin. ‘Power Space Violence’. ‘Generosity and Violence’. Why so much ‘violence’ in architecture and urban planning? ¿Isn’t architecture art?

And in doing so to question if the problem is less architecture and urban planning per se, but much more that as a global society we don’t fully appreciate, are often blinded by storytelling and expensive PR campaigns to a reality, that while architecture and urban planning can be a Geschenk, they can also be poison. All blithely appreciate architecture and urban development as intrinsically good. Because that’s how the (hi)story of architecture is presented. Invariably by architects. How often do the users of architecture and urban planning get control of the narrative? How often are stories of architecture told by users? And how often by architects?

And thereby as an exhibition The Gift very satisfyingly employs the architectural bequest, very satisfyingly employs one of the oldest expressions of architecture, as a conduit for access to considerations on, appreciations of, the responsibility of us all, individually and collectively, to consider in more detail than we currently do, to discuss more openly than we currently do, the social bonds generated and destroyed by any architectural and urban planning project, the means by which architecture is produced, the balance between generosity and violence in a project, because there inevitably will be a balance. But for all our responsibility to consider the afterlife of a project, once the architects and developers and politicians and media have moved on. Once the ‘vision’ has imploded. ¿What then?

Considerations that are all the more important when that architecture or urban planning project isn’t self-initiated, isn’t one a community actively sought, but is gifted. For, as we all know from bitter experience, while gifts can be a source of joy, they needn’t be.

Or as Virgil would probably have phrased it, timeō Architecte et dōna ferentēs

The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture is scheduled to run at the Architekturmuseum der TUM in der Pinakothek der Moderne, Barer Str. 40, 80333 Munich until Sunday September 8th.

Full details, including information on the accompanying fringe programme, can be found at www.architekturmuseum.de/the-gift

A discussion on the apartment of family Damdinsuren in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

Seminar projects by students from Munich and Ann Arbor, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

Timeline of aid for Skopje, North Macedonia, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

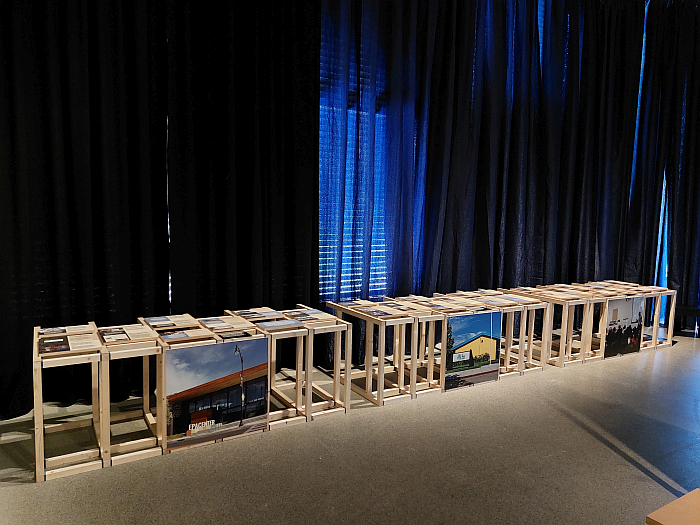

Photos of housing estates in Skopje, North Macedonia by Mila Gavrilovska, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

Documentation of the rebuilding projects in Skopje, North Macedonia, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

An introduction to Kenzō Tange’s plan for Skopje, North Macedonia, as seen in The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence in Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München

1. The exhibition texts are all in English but with handouts in German and Leichte Sprache, a simplified German. Except that is in the chapter with the results of the student seminars, there the Munich students’ work is in German and the Ann Arbor students’ work in English. Which makes no sense at all, but is so.

Tagged with: Architecture, Architekturmuseum der TU München, East Palo Alto, Kumasi, München, Munich, Skopje, The Gift. Stories of Generosity and Violence, Ulaanbaatar